Getting to Yes | Summary and Key Lessons

“Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In” is a seminal work in the field of negotiation, written by Roger Fisher and William Ury of the Harvard Negotiation Project. The book, first published in 1981, provides a comprehensive, step-by-step strategy for coming to mutually satisfactory agreements in every sort of conflict.

The strategy is based on the concept of principled negotiation, a method designed to arrive at the essence of a dispute and resolve it through a process that is fair and mutually beneficial.

Getting to Yes Summary

The authors begin by defining the problem with typical negotiation methods, focusing on the adversarial and position-based strategies that often lead to deadlock and dissatisfaction.

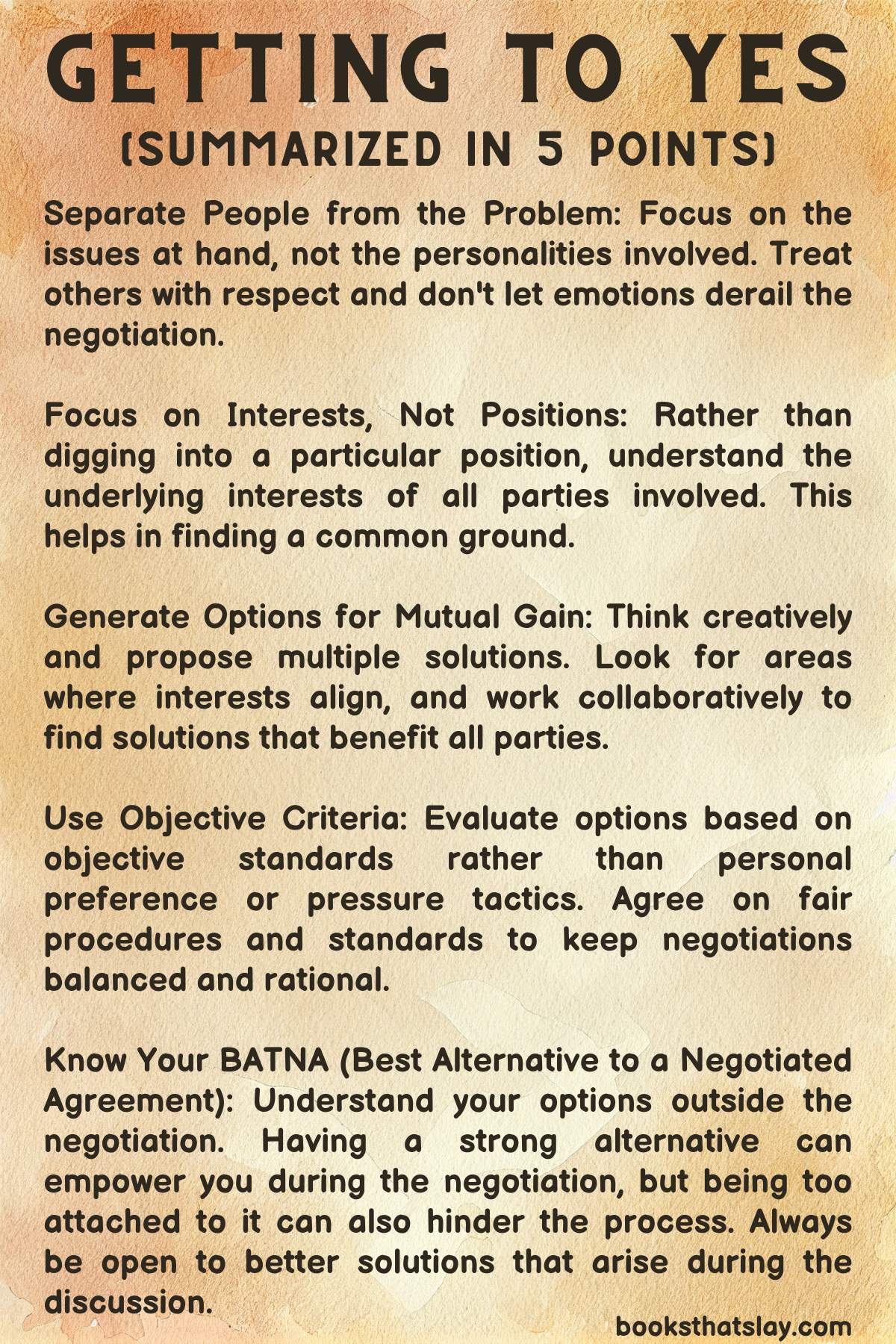

1. Separate the People from the Problem

Fisher and Ury advocate for separating relationship issues (or “people problems”) from the substantive issues at hand. By treating the other side as a partner rather than an adversary, negotiators can address interpersonal issues independently and maintain a collaborative attitude.

2. Focus on Interests, Not Positions

The authors distinguish between positions (what a party says they want) and interests (the underlying reasons for that want). They argue that focusing on underlying interests rather than rigid positions opens the door to creative problem-solving. By understanding and acknowledging the other side’s interests, negotiators can find common ground and discover mutually beneficial solutions.

3. Invent Options for Mutual Gain

This section stresses the importance of creativity in negotiations. Instead of fighting over a fixed pie, parties should look for ways to expand the pie by inventing options that satisfy the interests of all involved. This requires a willingness to think outside the box, to brainstorm without judgment, and to explore a wide range of possibilities.

4. Insist on Using Objective Criteria

To avoid arbitrary and biased decision-making, Fisher and Ury advocate using objective criteria and standards. By agreeing on fair procedures and external benchmarks, parties can evaluate options and arrive at a solution that’s justifiable to both sides.

5. Know Your BATNA (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement)

The authors introduce the concept of BATNA as a measure of a negotiator’s power. Knowing your best alternative if the negotiation fails helps you understand when to walk away and ensures that you don’t accept unfavorable terms. A strong BATNA provides leverage, while a weak BATNA may call for an adjustment in approach.

6. Negotiation with Hard Bargainers

This section provides advice on dealing with parties who refuse to play by the principles laid out in the book. The authors recommend staying on course with principled negotiation, avoiding reactive behavior, and using tactical approaches such as exploring their interests, reframing, or using a third-party mediator if necessary.

Also Read: The Body Keeps The Score Summary

What can you learn from the book?

1. Separate the People from the Problem

Example: Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario in a business setting. Two co-workers, Alice and Bob, are in a disagreement about the direction of a project. Bob believes they should focus on innovative ideas and technologies, while Alice argues for improving existing systems and processes. Tensions are running high, and their personal relationships are strained.

Lesson: The authors advise that in situations like these, it is recommended to separate people from the problem. It means addressing the issue at hand without letting personal biases or emotions dictate the process.

In this example, Alice and Bob’s negotiations would be more productive if they focused on finding a middle ground for the project’s direction rather than letting their personal conflicts drive the conversation.

This strategy helps ensure that negotiations remain objective, solutions-oriented, and free from personal animosities.

2. Focus on Interests, Not Positions

Example: In a real estate negotiation, a homeowner wants to sell their property at a high price, while the buyer insists on a lower price. They both appear to have opposite and irreconcilable positions.

Lesson: The key insight from the book is that successful negotiation requires focusing on underlying interests, not the apparent positions. In the above example, the homeowner might want a high price to pay off a debt, while the buyer may want a lower price to keep their mortgage payments manageable.

By focusing on these interests, it’s possible to find creative solutions that satisfy both parties. For example, they could agree on a price that allows the homeowner to pay off their debt, but with a structured payment plan that keeps the buyer’s monthly mortgage payments within their budget.

Also Read: Psycho-Cybernetics Summary

3. Invent Options for Mutual Gain

Example: A small business is struggling to meet its deadlines because one of its suppliers is consistently late with deliveries. The business owner is considering terminating the contract, but this would be costly and time-consuming.

Lesson: The parties involved in a negotiation should strive to invent options for mutual gain. It encourages thinking creatively beyond the obvious choices to find solutions that benefit all parties.

In this case, instead of immediately canceling the contract, the business owner could discuss the problem with the supplier and work together to come up with a solution that benefits both.

Maybe the supplier can expedite delivery for a small increase in price, which the business owner could offset by passing a part of it to its customers or by increasing efficiency elsewhere. This approach encourages collaboration and strengthens relationships between negotiating parties.

4. Use Objective Criteria

Example: Consider a company deciding between two employees for a promotion. Both candidates are valuable assets and have similar experiences and qualifications, making it a difficult decision. There may be subjective biases at play, either personal or departmental, that could potentially influence the decision unfairly.

Lesson: ‘Getting to Yes’ suggests using objective criteria as a key principle in negotiations or decision-making processes. This allows decisions to be made fairly and avoids bias or favoritism.

In the promotion scenario, the company could establish clear, objective criteria for the decision, such as performance data, specific achievements, leadership qualities, or feedback from colleagues and superiors.

By basing the decision on these measurable factors, the company ensures the process is transparent and fair.

Moreover, both candidates will likely accept the outcome as they know that the decision was made based on impartial and pre-agreed criteria, reducing potential conflicts or dissatisfaction.

Final Thoughts

In summary, “Getting to Yes” offers a groundbreaking and highly influential framework for negotiation that emphasizes cooperation, mutual respect, and innovative problem-solving. Its focus on interests rather than positions, its call for creativity, and its insistence on objective fairness have shaped the way negotiation is taught and practiced around the world.

The success of “Getting to Yes” led to a series of follow-up works by Ury and others, expanding on these ideas and exploring other aspects of negotiation and conflict resolution.

Also Read: