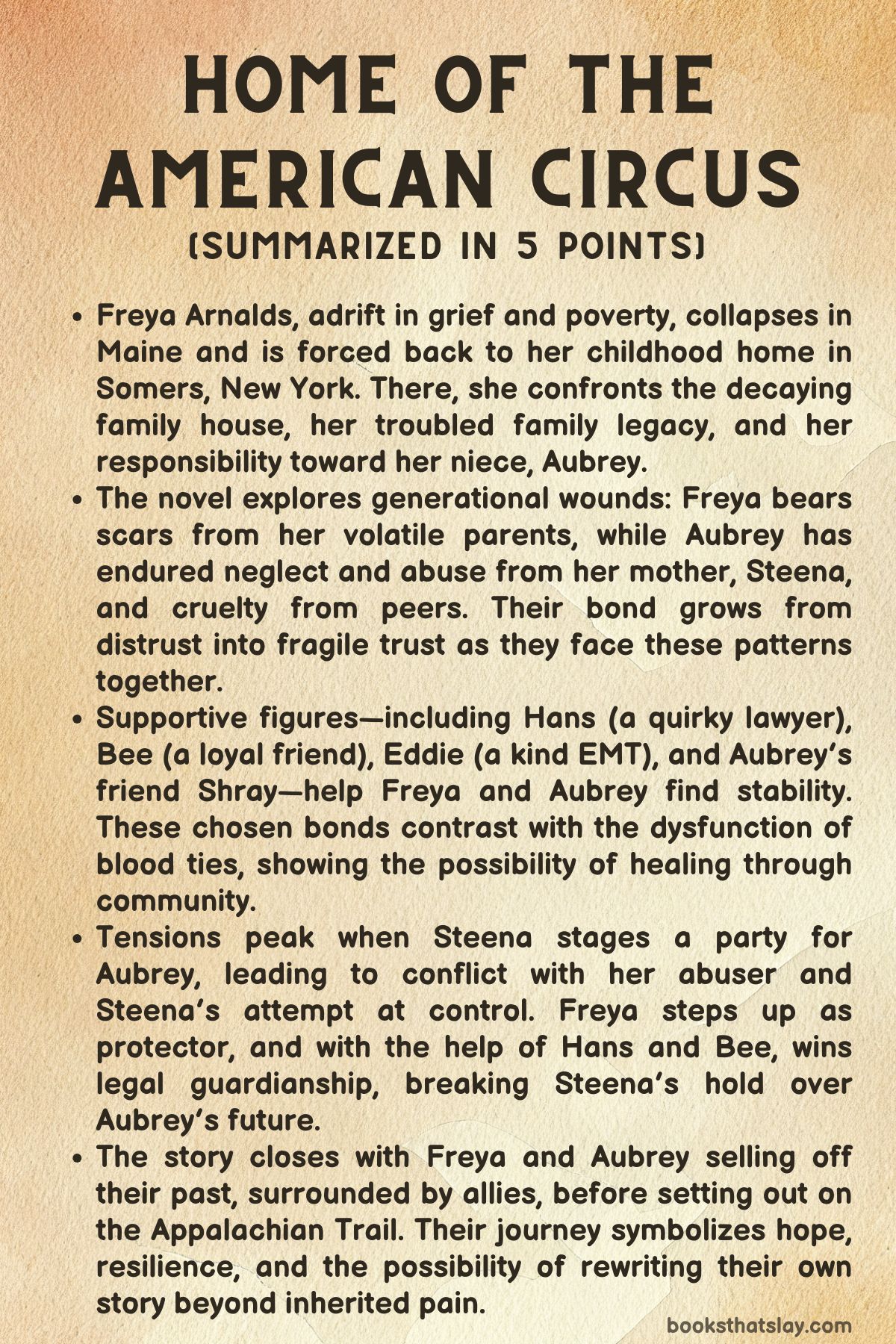

Home of the American Circus Summary, Characters and Themes

Home of the American Circus by Allison Larkin is a story about loss, survival, and the fragile bonds that hold families together. At its center is Freya Arnalds, a woman struggling with grief, poverty, and fractured relationships.

Forced back to her childhood home in Somers, New York, she confronts both her troubled family history and her responsibility toward her niece Aubrey. Together, the two navigate neglect, trauma, and the weight of the past while learning to create new paths for themselves. Through memory, myth, and the persistence of love, the novel explores how cycles of pain can be broken and replaced with hope.

Summary

The story opens with Freya recalling a luminous childhood moment: a drive with her niece Aubrey under a sky awash in orange light, music spilling from the car speakers. This memory comforts her even as it underscores all she has lost.

Alongside this recollection runs the recurring local legend of Old Bet, the circus elephant once paraded through Somers. The story of Old Bet—captivity turned into spectacle—frames the novel’s themes of distorted histories, trauma, and the search for belonging.

Freya’s present-day life in Maine is bleak. She works endless bar shifts, lives alone in a shabby apartment, and numbs herself with alcohol.

After collapsing at work, she wakes in the hospital to the fleeting kindness of a nurse, highlighting the emptiness of her support system. Returning home, she finds an eviction notice.

With no money, deteriorating health, and few options, she decides to leave Maine for Somers, the only place left to her after inheriting her parents’ decaying house. Her sister Steena inherited the money; Freya got the crumbling property.

Her journey back is exhausting, fogged by painkillers and regret. The house she inherits is overgrown, falling apart, and full of ghosts from the past.

Memories of her volatile mother and cruel sister resurface in every corner. The structure itself becomes a metaphor for neglect and disappointment.

Hans, an eccentric but kind lawyer, helps with the legal paperwork and becomes a rare source of encouragement. Yet Freya’s homecoming is reluctant, marked more by burden than comfort.

Seeking connection, Freya reunites with Jam, her childhood best friend and almost-love. Once a piano prodigy, Jam is now undone by addiction and grief.

Their bond is a lifeline, rekindling the comfort of old friendship, though tinged with the sorrow of wasted potential. Through Jam, Freya rediscovers the possibility of connection but is reminded of how fragile survival can be.

Hints soon reveal Aubrey’s secret presence in the house: fennel in the refrigerator, a rat named Lenny Juice in the sunroom. When Freya finally reunites with her niece, the encounter is tense.

Aubrey is resentful and fiercely independent, having endured her mother Steena’s neglect. She has been surviving by selling furniture and managing on her own.

Her resourcefulness reflects both her resilience and the depth of her pain. Freya is torn between pride and guilt, recognizing Aubrey’s independence while mourning the childhood she never should have had to endure.

A crisis pushes them closer when Freya’s attempt to bleach her hair goes wrong, and Aubrey rushes her to Dr. Singh, a retired family friend.

His gentle care provides rare stability, cementing Freya and Aubrey’s fragile bond. The strange, decaying house, with its bird heads brought in by a cat and lingering memories, mirrors the uneven progress of their healing.

Freya struggles to carve out a life in Somers. She finds work at a local restaurant, starts carving furniture, and begins to build tentative roots.

Eddie, a kind EMT, enters her life as a romantic partner, showing her a model of steady and patient love. Yet her regrets linger: her failures as an aunt, her distance from Jam, and the ache of unresolved grief.

The broken house becomes a symbol of her patched but never-whole self.

Aubrey confides a deeper trauma: she was sexually assaulted by Carter, a classmate, and bullied afterward. The adults in her world either ignored or reinforced the cruelty.

Freya is forced to face the painful truth that she cannot shield Aubrey from every harm. Their fragile household is further threatened when Steena reappears, furious at Freya’s return, determined to reassert control.

The small-town atmosphere amplifies the tension; secrets are hard to keep, and gossip makes survival even harder.

The story reaches a climax at Aubrey’s birthday party, staged by Steena for appearances. The event unravels into confrontation: Carter menaces Aubrey, while Steena and her partner Charlie try to control the story.

Freya, with Aubrey’s friend Shray, orchestrates a rescue. For the first time, Freya openly challenges her sister and claims her role as protector.

Aubrey, too, makes a defining choice, aligning herself with Freya and her chosen family instead of the biological one that has failed her.

In the aftermath, Hans and Bee, Aubrey’s guidance counselor, help Freya secure legal guardianship. With evidence of Steena and Charlie’s shady dealings, they navigate the legal battle.

Despite threats and blackmail, they succeed. Aubrey is finally free to live with Freya and define her own path.

This hard-won victory marks a turning point: for the first time, both aunt and niece glimpse a future free from Steena’s shadow.

The novel closes with a mixture of farewell and new beginning. Freya and Aubrey sell off their belongings in a community studio sale, releasing the past piece by piece.

Friends and allies gather, affirming the bonds they have built. With their affairs in order, they leave Somers to embark on a hike along the Appalachian Trail.

The trail is both literal and symbolic: uncertain, challenging, yet full of possibility. As they set out together, the weight of the past lingers, but the story ends with the promise of self-determined beginnings and the quiet hope of healing.

Characters

Freya Arnalds

Freya is the heart of the novel, a woman deeply marked by loss, guilt, and the complicated ties of family. She begins the story fragmented—living a hollow routine of bar shifts, hangovers, and fleeting escapes—but her collapse forces her into reckoning with her vulnerability.

Freya’s emotional world is heavy with longing and regret, particularly toward her niece Aubrey, whom she both failed and desperately wants to save. The inheritance of the decaying family home in Somers becomes a turning point, a place where she must confront her parents’ failures, her sister’s cruelty, and her own capacity to nurture.

Her growth lies in choosing to embrace responsibility rather than run from it, standing up against Steena and Charlie, and finally claiming guardianship of Aubrey. Through small but powerful acts of courage, Freya learns to break the cycle of abandonment, discovering love in the kindness of Eddie, solidarity in Hans and Bee, and hope in Aubrey’s resilience.

Aubrey Wells

Aubrey, Freya’s niece, embodies both the scars and the defiance of growing up neglected. Shaped by Steena’s cruelty and her peers’ bullying, she has built herself into a survivor—fiercely independent, secretive, and brimming with creativity.

Her rat, Lenny Juice, and her art serve as outlets for pain and tokens of resilience, reflecting her determination to craft meaning in a hostile world. Aubrey’s relationship with Freya is complicated: she oscillates between distrust and dependence, seeing her aunt as both a source of disappointment and a potential anchor.

Her journey is one of reclaiming power—from confronting Carter, to resisting her mother’s manipulation, to choosing Freya as her guardian. By the novel’s end, Aubrey emerges not as a victim but as an active author of her story, walking alongside Freya into a future of possibility.

Steena Russo

Steena is both villain and victim in the novel, embodying the destructive cycles of generational pain. As Freya’s older sister and Aubrey’s mother, she is consumed by her obsession with image, control, and bitterness.

Her interactions with Freya are tinged with rivalry and cruelty, while with Aubrey she shifts between neglect and punishment, unable to accept her daughter’s difference. Yet beneath her harsh exterior lies the residue of her own childhood wounds, marked by their mother’s volatility and the disappointment of unrealized dreams.

Steena’s character illustrates how trauma perpetuates itself, turning love into control and insecurity into aggression. Though she is monstrous in her treatment of Freya and Aubrey, the novel hints at her brokenness, making her as pitiable as she is destructive.

Jam

Jam is perhaps the most tragic figure in the story—a prodigy whose gift of music became both his salvation and his undoing. Once a celebrated pianist, he is now scarred by grief, addiction, and the crushing weight of expectation.

His bond with Freya is intimate and enduring; they are bound by shared history and mutual recognition of each other’s brokenness. To Freya, Jam is both a reminder of lost potential and a source of comfort, their closeness offering safety in a world of disappointment.

Yet Jam cannot fully escape his demons, and his life is a delicate balance between brief moments of hope and the heavy pull of despair. He stands as a symbol of what might have been, mirroring Freya’s own struggles with squandered possibility and fragile redemption.

Eddie Davis

Eddie represents a rare form of love in Freya’s world—steady, kind, and quietly transformative. As an EMT, he embodies care and resilience, showing up when others falter.

His romance with Freya is gentle, marked not by fiery passion but by the tender challenge of trust. Unlike Jam or Steena, Eddie does not represent drama or disappointment; instead, he is the possibility of stability, the idea that healing can be nurtured in the safety of consistent affection.

His presence offers Freya a model of healthy love, something she never believed she could deserve. Eddie’s role may not dominate the narrative, but his significance lies in being a living counterpoint to the dysfunction that surrounds Freya.

Hans Gruenberger

Hans, the quirky lawyer, is one of the novel’s quiet champions of chosen family. He enters Freya’s life through the legalities of her inheritance but quickly becomes more than a professional ally.

Eccentric yet compassionate, Hans provides both practical support and emotional steadiness. His acceptance of Freya without judgment is a stark contrast to the conditional, often toxic love she has known from her family.

His role is pivotal in securing Aubrey’s freedom, and his presence symbolizes the possibility of creating bonds outside of blood ties. Hans demonstrates that family can be chosen, and that kindness can be as revolutionary as confrontation.

Bee (Bridget Shulman)

Bee is Freya’s childhood friend who evolves into a vital connection across generations as Aubrey’s guidance counselor. Empathetic, loyal, and fiercely protective, Bee bridges the gap between Freya’s past and Aubrey’s future.

She represents the persistence of true friendship—the kind that survives distance, neglect, and time. Bee’s advocacy during the guardianship battle underscores her importance, as she becomes a linchpin in securing Aubrey’s freedom from Steena and Charlie’s control.

Her character emphasizes the value of allies who persist quietly but powerfully, demonstrating the ways that community can stand against dysfunction.

Shray Singh

Shray, Aubrey’s best friend, brings a sense of light and hope to the novel. An artistic and openly queer character, Shray offers Aubrey unconditional acceptance and companionship.

His family, supportive and loving, contrasts sharply with Aubrey’s fractured home life, giving her a vision of what belonging could look like. Shray embodies joy, resilience, and creativity, helping Aubrey hold onto possibility even amidst her trauma.

For Freya, he is a reminder that Aubrey can find connection outside of the toxic family unit. His role, though secondary, radiates warmth and reassurance, showing how chosen family and friendship can be lifelines.

Step (Freya’s Father)

Step is a spectral presence in the story, more remembered than active. He represents the ache of unrealized potential and the failures of parental protection.

His dreams, recorded in his notebooks, stand as both inspiration and disappointment—ambitions left unfinished, promises left unkept. For Freya, he is a source of deep pain, a reminder of how those meant to shield her instead left her vulnerable.

Step’s memory looms over the decaying family home, tying the physical collapse of the house to the emotional neglect that shaped Freya’s childhood. He embodies the tragic weight of what might have been.

Lenny Juice (the Rat)

Though small and seemingly insignificant, Lenny Juice, Aubrey’s pet rat, carries profound symbolic weight. As a creature often maligned or overlooked, he mirrors the characters’ own feelings of being unwanted or misunderstood.

For Aubrey, he is a source of comfort, a companion who survives alongside her in neglect. His death, marked by a Viking funeral, becomes a communal act of mourning and healing, emphasizing the novel’s theme that every life, no matter how small, holds value.

Lenny Juice is both a symbol of resilience and a reminder of the fragile joys that sustain survival.

Themes

Memory and Loss

In Home of the American Circus, memory is presented not as a stable repository of truth but as a shifting, fragile space where joy and pain coexist. Freya’s recollection of the sunlit drive with Aubrey embodies this duality—an image drenched in warmth and color yet haunted by the knowledge of what has been lost.

The memory comforts her with a fleeting sense of connection but also cuts deeply, highlighting the absence and loneliness that dominate her adult life. The novel treats memory as both salvation and torment: a way to preserve fragments of love but also a reminder of the permanence of loss.

This complexity is amplified by the prologue’s evocation of the American circus and the myth of Old Bet. Just as history rewrites and repackages the story of the elephant to serve spectacle and legacy, Freya rewrites her own past in flashes of recollection that blur the line between truth and longing.

The narrative insists that memory cannot be separated from trauma, for it shapes identity as much through wounds as through joy. The interplay of longing and absence underscores how deeply personal grief is mirrored in collective mythmaking—the human need to find meaning in stories, even when they are distorted, incomplete, or painful.

In this sense, loss is not simply a theme but the lens through which memory is filtered, shaping every decision Freya makes and every bond she struggles to preserve.

Isolation and Survival

Freya’s existence in Maine reveals the crushing weight of isolation and the exhausting struggle for survival that defines her life. Her world, confined to dimly lit bars, unhealthy food, and unreliable companions, is depicted with a bleakness that mirrors her inner emptiness.

The collapse at work functions not only as a medical crisis but as a symbolic breaking point, where her physical body reflects years of emotional exhaustion and neglect. The hospital scene, with its fleeting kindness from a nurse, underscores how starved she is for care and how vulnerable she has become in a world that offers her little stability.

This theme extends beyond mere loneliness; it interrogates what it means to survive when the scaffolding of community, family, and purpose has collapsed. Her eviction further compounds this struggle, stripping away the little security she had left and forcing her back to a place she never wanted to return to.

In this way, survival in the novel is not depicted as heroic resilience but as a weary endurance of daily humiliations, small compromises, and fleeting gestures of kindness. Freya’s survival, precarious and fragile, speaks to the broader human need for connection in a society that often abandons those who stumble at the margins.

Family Legacy and Inheritance

The inheritance of the Somers house represents more than a transfer of property; it embodies the weight of unresolved history and the suffocating presence of generational pain. Freya’s return to the decaying house is marked by ambivalence—it is not a gift but a burden, a structure saturated with memories of dysfunction and disappointment.

The house itself becomes a living symbol of her father’s unrealized dreams, her mother’s volatility, and her sister’s cruelty, reflecting how physical spaces can absorb and echo human suffering. The crumbling walls and overgrown yard suggest a past that has never been properly confronted, only allowed to rot.

This theme extends to the broader mythic history of the town, where the story of Old Bet echoes the way families, too, curate their own narratives—emphasizing pride while concealing shame. For Freya, inheritance is not just about bricks and beams but about being forced to reckon with a legacy of neglect, betrayal, and silence.

To occupy the house is to step into the unresolved conflicts of her childhood, and her attempts to live within it become a struggle to reclaim agency against the weight of history. Ultimately, inheritance in the novel is not financial or material wealth but the challenge of confronting ghosts—those of the past and those that still linger within.

Cycles of Trauma and the Possibility of Healing

Freya and Aubrey’s relationship lies at the center of the novel’s exploration of generational trauma and the fragile hope of healing. Both bear the scars of neglect and cruelty, Freya from her parents and Aubrey from her mother Steena.

Their bond is therefore marked by both recognition and fear: recognition of shared wounds and fear that they might repeat old patterns. The discovery of Aubrey’s secret stays in the house exemplifies this dynamic—her resourcefulness speaks to resilience, yet it is born of necessity in the absence of nurturing adults.

The rat in the sunroom becomes emblematic of their shared position as outcasts, creatures overlooked or dismissed yet stubbornly surviving. The cycle of trauma surfaces most explicitly in Aubrey’s confession of abuse and bullying, where the failure of adults to protect her mirrors Freya’s own childhood experience.

Yet within this cycle, the novel carves out moments of possibility: Aubrey’s art, Freya’s furniture carving, and their shared small victories suggest that healing, while never complete, can take root in creativity and chosen bonds. The struggle to protect Aubrey becomes Freya’s own attempt at redemption, proof that while the past cannot be erased, its patterns need not be repeated.

Healing, in this sense, is less about closure and more about carving out fragile spaces where trust, care, and resilience can exist despite everything.

Belonging and Chosen Family

In contrast to the biological family marked by neglect and betrayal, Home of the American Circus emphasizes the redemptive power of chosen family. Characters like Jam, Hans, Bee, and Eddie create a web of support that sustains Freya and Aubrey when blood ties fail.

Jam offers the comfort of being truly known, despite his own brokenness; Hans provides practical help and emotional steadiness; Bee bridges past and present through her loyalty; Eddie models the possibility of love rooted in patience and care. Even Shray, Aubrey’s friend, represents a hopeful counterpoint to the dysfunction of her home life, showing what acceptance and unconditional support can look like.

These relationships highlight how belonging is not guaranteed by kinship but earned through care, recognition, and mutual trust. The town itself, with its suffocating smallness, is both a source of threat and a backdrop where these alternative bonds are forged.

By the end, the communal studio sale and the Appalachian Trail journey suggest that belonging is less about a fixed place and more about the people who walk beside you. Chosen family becomes the antidote to inherited trauma, the fragile but vital proof that love can be remade even after repeated betrayals.

Rewriting History and Reclaiming Agency

The motif of Old Bet, the circus elephant, underscores the novel’s interrogation of who controls the narrative of history and how those narratives shape identity. Just as the story of the elephant has been recast over time to suit the needs of spectacle, the characters in the novel wrestle with distorted family stories, scapegoating, and the erasure of pain.

Aubrey’s bullying at school, rooted in lies and manipulation, reflects the same dynamic on a smaller scale—how narratives are weaponized to maintain power. Freya’s eventual confrontation with Steena and Charlie, and her securing of guardianship over Aubrey, represents an act of rewriting history on a personal level.

By refusing the roles imposed on them—scapegoat, outcast, failure—Freya and Aubrey reclaim their agency. The act of selling off belongings, of leaving the house behind, and of setting out on the Appalachian Trail signifies a conscious rewriting of their own story, a refusal to let inherited narratives define them.

In this way, the novel asserts that history, whether collective or personal, is not fixed but contested—and that reclaiming agency begins with the courage to tell one’s own version of events.