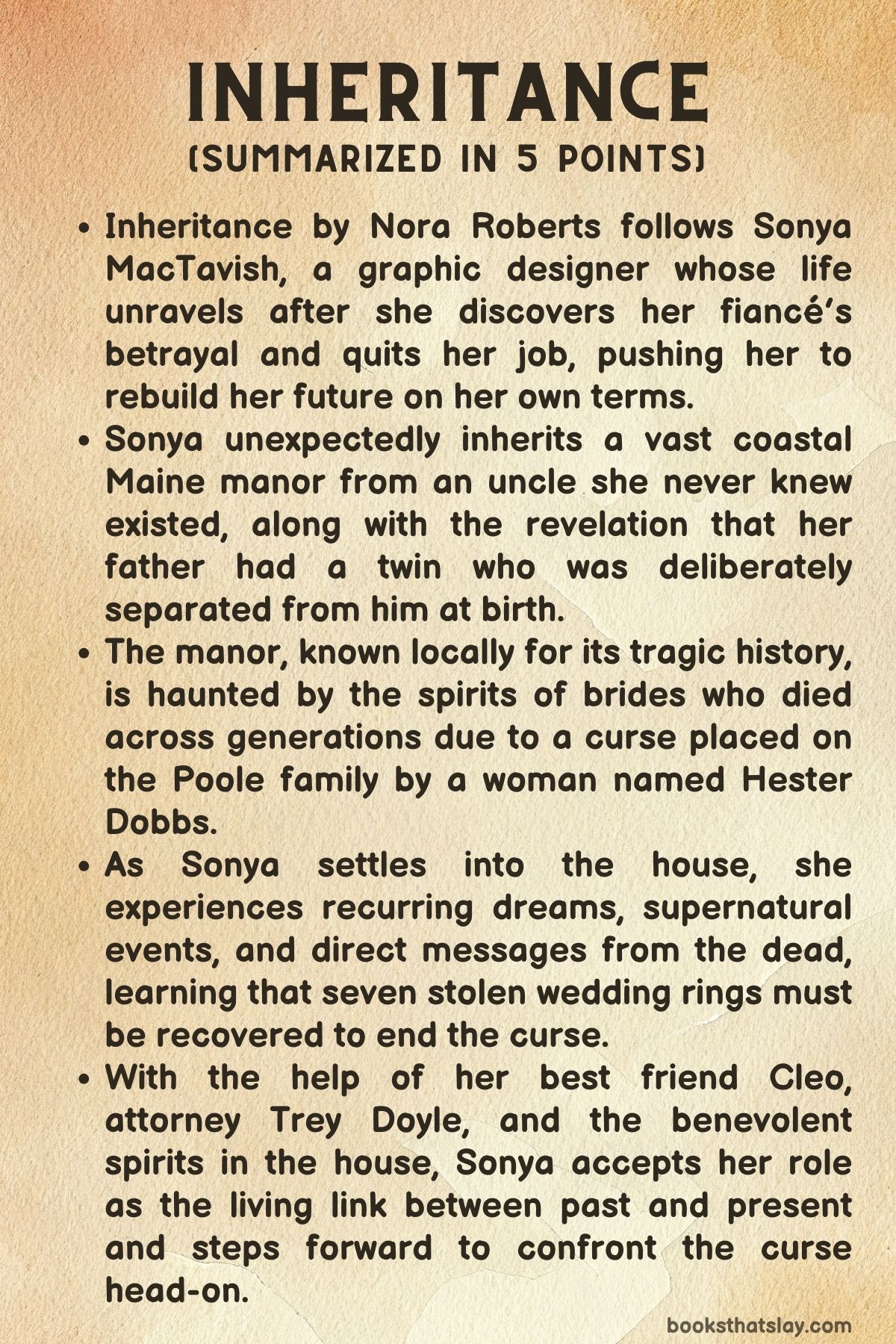

Inheritance by Nora Roberts Summary, Characters and Themes

Inheritance by Nora Roberts is a modern gothic-leaning romantic suspense with a strong supernatural mystery at its center.

After a broken engagement upends her carefully built life, Sonya MacTavish learns she has unexpected family ties to a coastal Maine town—and to a grand, isolated estate locals call Lost Bride Manor. The gift comes with conditions, and the house comes with company: lingering spirits, repeating signs, and a violent curse that has followed generations of brides. As Sonya starts over, builds a new career, and forms new bonds, she also becomes the one person the dead seem determined to guide.

Summary

In 1806, Astrid Grandville marries Collin Poole in Poole’s Bay, Maine, thrilled by the life she expects to build with him in his manor. During the celebration, a stranger named Hester Dobbs approaches Astrid, stabs her, steals her wedding ring, and pronounces a curse: Astrid will remain a bride forever, and the Poole family will keep losing brides. Astrid dies in Collin’s arms, and the manor’s history turns into a chain of grief anchored to that stolen ring.

More than two centuries later, Sonya MacTavish is a 28-year-old graphic designer in Boston, engaged to her coworker, Brandon Wise. Sonya wants a small wedding, but Brandon pushes for a showy event that makes her feel like she’s performing a role rather than celebrating love. Stressed and increasingly uneasy, she leaves work early one day and returns home to find Brandon in bed with her cousin Tracie.

The betrayal snaps something cleanly in her: she throws them out, calls her best friend and former college roommate, Cleo Fabares, and begins tearing down every piece of the wedding plan Brandon insisted on building. Her mother, Winter, arrives soon after, pulled into the mess by family phone calls, and helps Sonya pack Brandon’s things and reclaim the house.

The fallout spreads into Sonya’s job. Brandon has already spun a story to their bosses, painting Sonya as unstable and overworked. Sonya refuses to let him control the narrative, tells the truth, and keeps working with forced professionalism. Brandon responds with petty, escalating attacks—smear tactics, harassment, and sabotage that leaves Sonya suspecting he’s behind damage to her car and missing work files. Even with supportive supervisors, Sonya decides her peace is worth more than the paycheck. She resigns on good terms, takes a valued client account with her, and commits to building a freelance design business from scratch.

As she settles into her new routine, an attorney named Oliver Doyle II—known as Deuce—appears with news that doesn’t fit the story Sonya has always been told about her father, Andrew. Deuce explains that Andrew had a twin brother, Collin Poole, and that Sonya has been named the heir to Collin’s estate: a vast Victorian-Gothic manor in Poole’s Bay and the family legacy attached to it.

Sonya is stunned not only by the inheritance but by the revelation that Andrew’s early life was shaped by a deliberate separation. Their mother died giving birth; their father died soon after. A powerful grandmother, obsessed with appearances and the family name, kept one twin and sent the other into foster care, erasing the truth with a convenient lie.

Sonya’s first instinct is to refuse. A property valued at millions sounds like a trap, not a gift. Deuce assures her the will includes a trust to cover taxes, staff, and maintenance, plus a yearly stipend. There is, however, a condition: Sonya must live in the manor for three years.

Winter and Cleo listen as Sonya processes the shock, and Winter adds an eerie layer of her own—Andrew used to sketch the manor obsessively, as if he were drawing a place he’d never seen yet somehow remembered. He also sketched an ornate mirror and described dreams of someone who shared his face. After consulting Winter’s lawyer, Marshall Tibbetts, Sonya agrees to a trial move: she’ll live at the manor for three months, then decide whether to commit.

Sonya rents out her Boston home, packs her life into a car, and drives north. The manor is larger, stranger, and more beautiful than she expected, with towers, old stonework, and rooms that seem built to hold secrets. Trey Doyle—Deuce’s son—meets her at the property and welcomes her to the place everyone calls Lost Bride Manor.

Inside, Sonya notices a portrait of Astrid, a young bride with sadness in her eyes. Trey explains Astrid’s murder and the curse that followed, including another stories of later tragedies, like Collin’s wife Johanna, who died on their wedding day. Sonya begins to understand that the manor isn’t just an inheritance—it’s a history of unfinished lives.

The house overwhelms Sonya at first, but practical tasks help her cope: choosing rooms, setting up her office in a turret library, and planning how to handle a property too big for one person. Yet the manor refuses to behave like an ordinary building. Doors open after Sonya closes them.

Toiletries move. Her bed appears neatly made. Music plays without anyone touching a key. Sonya tries to explain it away as stress and forgetfulness, but the pattern returns, and the timing becomes hard to ignore. She begins waking at three in the morning to piano music, sobbing, and the heavy sense of being watched.

As Sonya builds relationships in town and starts getting work—designing a website for Trey’s sister, Anna—her connection to the manor intensifies. She has vivid dreams that aren’t simply dreams.

They place her in the lives of other Poole brides, showing their last moments: a woman lured outside in winter, collapsing in snow as Hester steals her rings; a mother dying in childbirth as Hester appears like a shadow to claim another wedding band; a bride choking during a celebration while Hester watches, satisfied. In one dream, Astrid speaks directly to Sonya and gives her a task: find seven missing wedding rings to break the curse. The message is clear—Sonya isn’t just living in the manor; she’s been brought here for a purpose.

Cleo comes to visit, falls in love with the place, and believes Sonya immediately when the strange signs appear. She decides to move in, trading rent for groceries, cooking, and a steady presence that keeps Sonya grounded. Trey and Sonya grow closer as well. He helps with practical matters, listens without mocking her fears, and gradually accepts that the house is active.

The dogs sense things, too—pausing to stare at empty corners, reacting to invisible hands. Sonya adopts a small rescue dog, Yoda, and the house seems to soften around the decision, as if approving of new life within its walls.

Still, the haunting has layers. Some presences are helpful: a spirit that cleans, folds laundry, and leaves small comforts behind. A playful child ghost teaches Yoda tricks and tosses him treats, turning the manor’s corridors into a strange kind of playground. Clover, the twins’ mother, seems able to communicate through music, selecting songs like signals. Sonya starts naming the presences by their habits and feels less alone, even when the house is quiet.

But there is also Hester—angry, controlling, and bound to a particular space known as the Gold Room. The temperature drops near its door. Windows slam. A sense of threat rolls out in waves.

At one point, Trey enters the room and the door locks behind him. The wallpaper appears to bleed, the wind turns violent, and he’s trapped until he declares the manor belongs to Sonya and refuses to be intimidated. Later, Hester escalates: a huge black bird bursts from the manor and dives at Sonya and Yoda before vanishing, a warning made physical. Cleo has her own terrifying encounter when Hester appears in a mirror behind her and leaves a message in steam: “Leave or die.”

The three o’clock pattern tightens. Sonya sleepwalks, drawn through the manor as if following instructions she can’t fully remember upon waking. During one episode, she speaks names from the past and describes how Hester feeds on fear and grief.

The night leads them to what they’ve been searching for all along: the ornate mirror Andrew drew again and again, hidden within the manor like a sealed door. When Sonya reaches it, the house falls into a tense silence. To Cleo and Trey, it looks like ordinary glass. To Sonya—and to Owen Poole, a cousin who has joined them—there is movement and color, as if another place is pressed against the surface.

Sonya feels a pull from the mirror that matches the sense of obligation she’s carried since arriving. She believes it is part of what she inherited, as real as the deed in her paperwork. Trey tries to stop her, afraid the mirror is a trap, but Sonya insists she has to go forward, not backward.

Cleo presses a protective charm into Sonya’s hand. Owen, sharing the family bloodline that seems to sharpen perception, takes Sonya’s other hand. Together, they step through the mirror, and the manor goes completely still behind them.

Characters

Sonya MacTavish

Sonya is the emotional and narrative center of Inheritance. At the beginning of the story, she is competent, creative, and conflict-avoidant, willing to compromise her own desires to maintain peace in her relationship and workplace. Her betrayal by Brandon forces a reckoning that reshapes her identity.

Rather than collapsing, Sonya chooses self-respect, walking away from both her engagement and a toxic professional environment. Her move to Poole’s Bay becomes a symbolic and literal rebuilding of her life. As she settles into the manor, Sonya’s defining trait emerges as resilience.

She responds to fear with curiosity, to chaos with structure, and to the supernatural with steady resolve. Over time, she grows into a caretaker not just of the house but of its history, accepting the responsibility of confronting the curse rather than fleeing from it. Her ability to balance logic with openness allows her to bridge the worlds of the living and the dead, making her uniquely capable of completing the task the spirits entrust to her.

Trey Doyle

Trey begins as a grounded, practical presence, someone rooted in law, routine, and responsibility. As Deuce’s son, he carries both professional discipline and a quiet sense of inherited duty. His initial role is supportive rather than dominant, offering Sonya help without attempting to control her decisions.

Trey’s skepticism toward the supernatural softens gradually, not through blind belief but through firsthand experience and emotional investment. His growing relationship with Sonya opens him to aspects of the manor he once dismissed or avoided, including his own childhood encounters with spirits. Trey’s character is defined by protectiveness, patience, and integrity.

He respects Sonya’s autonomy even when afraid for her safety, and this restraint deepens their bond. His willingness to stand his ground against Hester in the Gold Room signals a turning point, showing that his strength lies not in denial but in loyalty and courage.

Cleopatra “Cleo” Fabares

Cleo serves as Sonya’s emotional anchor and chosen family. Confident, expressive, and intuitive, she contrasts Sonya’s more measured temperament while complementing it perfectly. Cleo believes Sonya without hesitation, offering validation rather than skepticism when the hauntings begin.

Her openness to the supernatural does not stem from naivety but from cultural memory and inherited belief, particularly through her grandmother. Cleo’s presence in the manor changes its emotional atmosphere, bringing warmth, humor, and creative energy.

She refuses to be intimidated by fear, even when directly confronted by Hester, and channels her anger into protective resolve rather than panic. As an artist, Cleo understands the power of memory and symbolism, which allows her to engage with the manor’s mysteries in a way that is emotional rather than analytical. Her loyalty is unwavering, and her willingness to stand beside Sonya, even at personal risk, underscores the depth of their bond.

Hester Dobbs

Hester is the novel’s primary antagonist and the embodiment of obsessive entitlement and sustained malice. Her actions are driven by possessiveness and resentment, rooted in her fixation on Collin Poole and her belief that love is something to be claimed rather than shared.

Hester’s curse is not impulsive but calculated, repeating across generations with deliberate cruelty. Even in death, she seeks control, feeding on fear, grief, and disruption. Unlike the other spirits, Hester does not linger out of love or regret but out of refusal to release power. Her confinement to the Gold Room reflects both her strength and her limitation, as she can influence but not fully dominate the house.

Hester’s hatred of Sonya stems from recognition; she sees in Sonya the potential to undo what she has enforced for centuries. This makes Sonya a direct threat, shifting Hester from distant menace to active aggressor.

Astrid Grandville Poole

Astrid represents the emotional origin of the curse and the moral heart of the lost brides. Gentle, hopeful, and deeply loving, Astrid’s murder is both sudden and cruel, cutting short a life defined by promise. In death, she becomes a guiding presence rather than a passive victim.

Astrid’s spirit is calm, focused, and purposeful, directing Sonya toward the truth without overwhelming her. She does not seek vengeance but resolution, wanting the cycle of loss to end so no more brides are condemned. Astrid’s continued presence in the manor, often expressed through music and dreams, conveys sorrow without bitterness.

Her relationship with Sonya is marked by trust, positioning Sonya not as a replacement but as an ally capable of doing what Astrid never could in life.

Collin Poole

Collin exists largely through memory, art, and the structure of the manor itself. As a man shaped by loss, he is defined by devotion and grief. After Astrid’s death, his life narrows into mourning, preservation, and isolation. His later marriage to Johanna suggests a desire to heal, but her death reinforces the sense that happiness is forbidden within the Poole lineage.

Collin’s decision to maintain the manor and protect its legacy, even in despair, sets the stage for Sonya’s inheritance. Through his will, Collin makes an intentional choice to pass the responsibility to someone outside the immediate family line, suggesting both regret and hope. His presence lingers in the house not as a haunting force but as a silent steward, someone who built the foundation Sonya must now complete.

Johanna Poole

Johanna is remembered as kind, nurturing, and gentle, with a love for music and children that echoes through the manor long after her death. Her spirit is associated with the piano, expressing emotion through sound rather than speech. Johanna’s role among the spirits is protective and empathetic, often offering comfort rather than warning.

Her bond with Corrine and her continued presence suggest unfinished concern for those she left behind. Johanna’s death reinforces the cruelty of the curse, as she represents a second chance at happiness that is abruptly taken away. In the afterlife, she becomes part of the supportive network guiding Sonya, using music as a language of reassurance.

Clover Poole

Clover, the mother of Collin and Andrew, bridges generations through memory, music, and quiet guidance. Her separation from one of her sons is the result of others’ choices, not her own, and her lingering presence suggests unresolved grief over that loss.

Clover communicates through song, selecting music that conveys mood, warning, or encouragement. She acts as a protective maternal figure not only to Sonya but to the household as a whole.

Her ability to appear to Trey marks a shift in his connection to the supernatural and underscores the idea that emotional openness allows greater perception. Clover’s role is subtle but essential, reinforcing the theme that family bonds persist beyond death.

Deuce Doyle

Deuce functions as both legal guide and moral stabilizer. Professional, fair, and transparent, he ensures Sonya understands her inheritance without manipulation or pressure. Unlike previous generations who concealed or distorted truth, Deuce insists on clarity, breaking the cycle of secrecy that contributed to the family’s suffering.

His respect for Sonya’s independence is evident in how he presents options rather than directives. Deuce’s calm acceptance of the manor’s reputation suggests long familiarity with its history, and his quiet support helps normalize Sonya’s experience rather than sensationalize it.

Owen Poole

Owen represents the living continuation of the Poole family, grounded in work, tradition, and responsibility. Practical and steady, he does not romanticize the manor but respects its weight.

Owen’s shared bloodline allows him heightened perception during key moments, particularly in relation to the mirror.

His protective instincts extend to Sonya and Cleo, even when he does not fully understand what is happening. Owen’s willingness to step through the mirror with Sonya reflects trust and courage, as well as a desire to help correct the damage done by his ancestors.

Winter MacTavish

Winter is a steady, thoughtful presence whose perspective adds emotional depth to Sonya’s journey. She carries the quiet pain of her husband’s lost past and recognizes the echoes of that loss in the manor.

Winter’s refusal to remove Andrew’s painting reflects her respect for history and her understanding that some things belong where they originated.

Her openness to sensing Andrew’s presence suggests that grief, when acknowledged rather than denied, can become a source of connection rather than paralysis. Winter supports Sonya without trying to shield her from hard truths, trusting her daughter’s strength.

Molly O’Brian

Molly is one of the manor’s most nurturing spirits, known for cleaning, organizing, and quietly caring for the household. Her actions express affection and pride rather than obligation. Molly’s presence softens the atmosphere of the manor, counterbalancing Hester’s hostility.

She represents the idea that service, when given freely, can endure beyond life. Her gentle humor and domestic rituals help transform the manor from a place of mourning into a livable home.

Jack

Jack, the child spirit, brings innocence and playfulness into a space shaped by tragedy. His bond with Yoda reflects his longing for companionship and joy.

Jack’s presence reminds Sonya and Cleo that not all loss is rooted in cruelty; some deaths are simply the result of fragile circumstances. His laughter and games inject warmth into the manor, reinforcing the theme that life, even after death, can still contain moments of happiness.

Brandon Wise

Brandon serves as a sharp contrast to the growth Sonya achieves. Charming on the surface but fundamentally selfish, he prioritizes image, control, and self-preservation over honesty. His infidelity is compounded by his willingness to manipulate professional systems to protect himself and undermine Sonya.

Brandon’s behavior demonstrates how betrayal is not limited to romantic relationships but can extend into reputational and emotional harm. His role in the story is brief but impactful, acting as the catalyst that pushes Sonya toward the path she was meant to take.

Themes

Inheritance, Legacy, and the Weight of the Past

From the moment Sonya learns that she is the heir to Lost Bride Manor, inheritance becomes more than a legal transaction; it becomes a moral and emotional burden shaped by history. In Inheritance, legacy is not something that rests quietly in documents or property lines. It arrives loaded with secrets, omissions, and unresolved harm that stretches across generations.

Sonya does not simply inherit a house; she inherits the consequences of decisions made long before she was born—decisions rooted in control, class anxiety, and the deliberate erasure of lives deemed inconvenient. The separation of the twins, Andrew and Collin, is central to this theme.

Their grandmother’s choice to keep one child and discard the other fractures the family line and plants the conditions that later allow the curse to persist. Legacy here is shown as something shaped as much by what is hidden as by what is preserved.

The manor itself functions as a physical record of this inheritance. Its rooms, portraits, and hidden spaces hold memory in a way that refuses silence. Sonya’s father unknowingly carried this legacy through dreams and art, sketching a house he never saw and a mirror he never touched, suggesting that inheritance operates beyond conscious knowledge. The book argues that legacy is not neutral; it presses forward until someone acknowledges it. Sonya’s role is not to passively accept what she has been given, but to confront it, question it, and decide what it will become next. The trust fund, the three-year residency requirement, and the ghosts all serve the same purpose: they force engagement rather than escape.

What makes this theme particularly resonant is that inheritance in the novel is not framed as privilege alone. Financial security exists, but it is paired with obligation and risk. Sonya must earn her inheritance by living with it, learning from it, and ultimately acting on it. The story suggests that true legacy is not about preserving a name or a structure but about responsibility—recognizing harm, refusing to repeat it, and choosing to break cycles rather than protect appearances.

Betrayal, Control, and the Abuse of Power

Betrayal in Inheritance operates on both an intimate and systemic level, revealing how personal violations echo larger patterns of control. Sonya’s discovery of Brandon’s infidelity is not treated as a simple romantic rupture. It exposes how control often hides behind charm, ambition, and social performance.

Brandon’s insistence on a grand wedding, his manipulation of their workplace narrative, and his retaliatory harassment after being exposed show betrayal as an assertion of dominance rather than a moment of weakness. His behavior mirrors the broader theme of men and institutions rewriting reality to protect themselves, a pattern that repeats across generations in the Poole family history.

This personal betrayal prepares Sonya for recognizing older, more dangerous forms of abuse. Hester Dobbs represents the most extreme expression of control: a woman who uses violence, curses, and fear to assert ownership over others’ lives. Hester’s fixation on brides, rings, and marriage rituals reveals betrayal as something tied to entitlement. She believes love and commitment can be claimed through force, and when denied, she punishes entire bloodlines. The curse is not random cruelty; it is a sustained attempt to dominate family futures long after her own life ends.

Institutional betrayal also plays a role. The grandmother who separated the twins did so under the guise of propriety and legacy preservation, but her actions betray basic moral responsibility.

The foster system that swallowed Andrew without explanation or support becomes another quiet betrayal, one that society allows to fade into anonymity. These layered betrayals reinforce the idea that harm persists when power goes unchallenged.

Sonya’s response to betrayal defines her growth. She refuses to protect Brandon’s reputation, refuses to minimize his actions, and later refuses to surrender her home to fear. By naming betrayal rather than absorbing it, she breaks its hold. The novel presents betrayal not as a singular event but as a structure that survives when silence and compliance allow it to.

Home, Belonging, and Chosen Family

The idea of home in Inheritance evolves from something fragile and conditional into something deliberately built. Sonya begins the story with a house in Boston that represents stability on the surface but is undermined by betrayal and emotional imbalance.

Once that relationship collapses, home becomes uncertain, tied less to place and more to trust. Lost Bride Manor initially appears as the opposite of safety: vast, unfamiliar, and crowded with unseen presences. Yet over time, it becomes the first space where Sonya is not expected to perform, accommodate, or shrink herself.

Belonging in the novel is not inherited automatically through blood. Sonya’s strongest sense of family comes from people she chooses and who choose her in return. Cleo’s decision to move into the manor transforms it from a site of isolation into a shared space defined by cooperation and humor.

Trey’s steady presence, grounded support, and refusal to dominate or rescue Sonya reshape her understanding of partnership. Even the ghosts participate in this chosen family structure. Their acts of care—cleaning, protecting, offering comfort—reframe haunting as companionship rather than threat.

The manor’s shift from a cursed house to a lived-in home happens gradually and intentionally. Sonya asserts boundaries, thanks the spirits, and claims ownership without denying the past. This balance is crucial. The novel suggests that belonging does not require erasing history, but it does require agency. Home becomes a place where fear is acknowledged but not obeyed, where memory exists without control.

By the time Sonya fully settles into the manor, home is no longer defined by walls or deeds. It exists in routines, shared meals, creative work, and mutual defense against harm. The story affirms that belonging is an active process, created through honesty, care, and the refusal to accept loneliness as inevitable.

Female Autonomy and Reclaiming Narrative Power

At its core, Inheritance is a story about women reclaiming authorship over their own lives after generations of silencing. The curse itself targets women at moments traditionally associated with transition into socially defined roles—marriage, motherhood, domestic stability. Each lost bride is reduced to a cautionary tale or a tragic footnote, her individuality overshadowed by the manner of her death. Hester’s fixation on rings symbolizes an attempt to define women solely by their relationships to men and to punish them for choosing autonomy.

Sonya’s journey directly challenges this pattern. She refuses to be reshaped by betrayal, refuses to abandon her career, and refuses to accept fear as destiny. Her decision to start her own business is not a side plot; it is a declaration of independence that runs parallel to her supernatural role.

Financial autonomy supports emotional autonomy, allowing her to face the manor and its dangers on her own terms. She does not wait for rescue, nor does she treat love as protection. Her relationship with Trey develops alongside her strength, not as a substitute for it.

The spirits of the lost brides gain voice through Sonya’s dreams, finally able to tell their stories rather than remain frozen in portraits. These women are not romanticized; their anger, sorrow, and unfinished lives are acknowledged. By agreeing to recover the stolen rings, Sonya participates in restoring what was taken from them: dignity, recognition, and closure.

Even Cleo’s presence reinforces this theme. Her creativity, spirituality, and refusal to dismiss the supernatural add alternative forms of knowledge that challenge rigid logic and control. Together, the women in the story model autonomy as something collective rather than isolated.

The novel ultimately frames autonomy as the right to define meaning—of love, of home, of inheritance—without surrendering that definition to fear, tradition, or force.