Joy Moody is Out of Time Summary, Characters and Themes

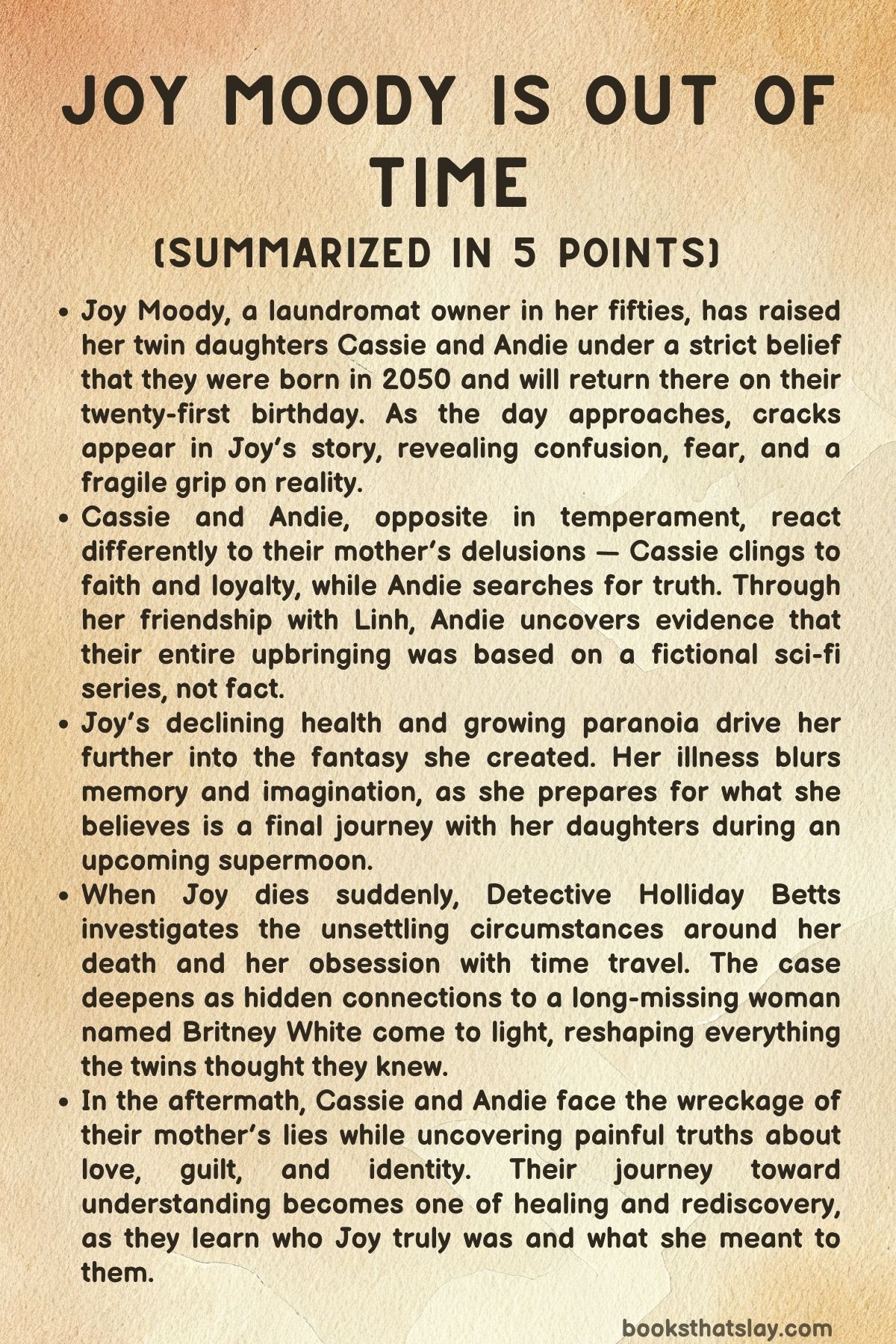

Joy Moody is Out of Time by Kerryn Mayne is a thought-provoking novel that examines the complexities of motherhood, memory, and truth through the life of a woman whose imagination becomes her only way to survive. Joy Moody, a laundromat owner in Melbourne, raises her twin daughters under an extraordinary lie—that they are time travelers from the future.

As her mind deteriorates from a brain tumor, the line between her delusion and reality blurs, setting off a tragic chain of events. The novel unfolds as both a psychological mystery and a story about love, guilt, and the fragile nature of belief.

Summary

Joy Moody lives with her twenty-year-old twin daughters, Cassie and Andie, in a modest home attached to her laundromat, Joyful Suds, in Bonbeach, Melbourne. Outwardly, Joy appears practical and organized, running her business with precision.

Beneath that order, however, lies a web of deception she’s spun over two decades. She has raised her daughters to believe they were born in the year 2050 and sent back in time to save humanity.

The story begins on August 1, 2023—the twins’ twenty-first birthday—when Joy expects the trio to return to the future. She makes them sit under a peppercorn tree, convinced it is their “time portal.” As hours pass and nothing happens, her conviction collapses. In the final moments before midnight, Joy realizes that her long-held fantasy has failed.

That same night, she dies under mysterious circumstances.

A few weeks earlier, Joy’s daily life seems uneventful but is marked by secrecy and decline. She hides her terminal brain tumor from her daughters and from her kind neighbor, Monty Doyle.

Her daughters, meanwhile, are opposites in temperament. Cassie, the quieter twin, dutifully believes everything her mother tells her.

She spends her days working in the laundromat and folding laundry with calm precision. Andie, curious and rebellious, senses something deeply wrong about their life.

Their mother has forbidden phones, computers, and schooling, claiming these things attract “The People” from the future who might track them down. When Andie confides her doubts to Linh, a tattoo artist next door, Linh helps her order a DNA test, suspecting that Joy’s elaborate tale is borrowed from a popular science fiction series, The Fortis Trilogy.

As Andie explores the truth, Joy’s behavior becomes increasingly erratic. Her illness fuels hallucinations and confusion between her real memories and the imagined world of her favorite books.

She convinces herself that she and the girls truly will travel forward in time under the upcoming supermoon. Meanwhile, Cassie, unaware of her mother’s condition, starts to experience small acts of rebellion.

She befriends Omar, a stranger who admires her sketches, and even shares a shy kiss—an act that infuriates Joy, who drags her home in a rage. The cracks in Joy’s control begin to widen.

When Andie finally receives the DNA test results, they confirm that she and Cassie are not related to Joy. Their biological father is a man named Tyler Rodriguez.

Cassie refuses to accept it, clinging to the story of their futuristic origins. Andie confronts Joy, accusing her of lying and controlling their lives.

The argument intensifies on the twins’ twenty-first birthday, when Joy prepares a champagne toast identical to the final scene in The Fortis Trilogy, where the heroines are poisoned by their guardian. Andie panics, smashing the glasses and accusing Joy of plotting to kill them.

Cassie tries to mediate, but the family’s fragile world collapses. Hours later, Joy Moody is dead.

Detective Sergeant Holliday Betts is assigned to investigate. The case is her first as a homicide detective, and she immediately senses that the situation is far from ordinary.

The laundromat is eerily pristine, but disturbing clues appear: a photo of Joy with a pin through her forehead and a note reading, “Time’s up, Joy. ” The twins’ odd behavior—claiming they were born in 2050 and lacking any identification—raises suspicion.

Surveillance footage reveals a man, Tyler Rodriguez, near the laundromat before Joy’s death, tying the case to a decades-old disappearance: Britney White, a missing teenager from twenty-one years earlier.

As Holliday digs deeper, she learns that DNA from the laundromat matches Britney White. Forensic teams uncover human remains buried in Joy’s shed—Britney’s body.

The revelation that Joy had kidnapped Britney’s twin babies and raised them as her own shocks everyone, including Cassie and Andie. Joy’s pre-death confession, found on a missing-persons website, states that Britney’s death was accidental.

It ends cryptically with, “I cannot answer your questions until 1 August 2050.

The discovery turns the story from mystery to tragedy. Holliday suspects Joy concealed her crime out of fear and guilt, fabricating the time-travel story as a way to justify what she had done.

Despite suspicions of foul play, the autopsy reveals that Joy died from natural causes related to her tumor. There’s no evidence of poisoning or external harm, and the case appears closed.

Still, Holliday feels the truth is incomplete.

The emotional aftermath for Cassie and Andie is turbulent. Their neighbor Monty and Linh take them in, while Joy’s brother, Grant, arrives to claim control over the laundromat.

Andie distrusts him and begins to see that Joy’s paranoia may have been partly rooted in real fears about losing the girls. When the twins find Joy’s hidden tablet and notebooks, they uncover her desperation—her terminal diagnosis, her guilt over Britney’s death, and her love for the girls she stole but cherished as her own.

Eventually, Monty reveals the full truth. On the night of her death, Joy, weak from illness and consumed by regret, asked Monty to help her die peacefully.

She confessed to accidentally killing Britney in a struggle years earlier, then raising her infants. That night, Joy injected herself with insulin before Monty could stop her, dying quietly in his arms.

He kept the secret to protect her memory and the twins.

The final chapters bring reconciliation and renewal. The police confirm the details of Britney’s death and rule Joy’s case a non-criminal death.

Monty discloses that Joy had left two wills—one giving him the laundromat, another naming the twins as rightful heirs. The community rallies around Cassie and Andie, forcing their manipulative uncle to withdraw.

Ellen, a lawyer and friend, helps them settle Joy’s estate.

The twins begin to rebuild. They scatter Joy’s ashes at the beach where she once found them, finally understanding that her love, though twisted by delusion, was genuine.

Cassie reconnects with her art and flirts shyly with Shawn, a vending machine worker. Andie forms a deeper friendship with Linh.

Together, the sisters renovate Joyful Suds, painting it white and reopening it as a symbol of new beginnings.

The story closes with a haunting flashback to 2002. A young Joy confronts Britney White, who tries to reclaim her babies.

In the struggle, Britney falls and dies. Joy, terrified and grieving, takes the twins, vowing to raise them better than Britney ever could.

That act of violence shapes every moment that follows—an unbreakable chain of love, guilt, and the illusions we create to protect the people we love most.

Joy Moody is Out of Time becomes, in the end, a story about how far a person will go to rewrite reality when truth is too painful to bear.

Characters

Joy Moody

Joy is the tragic engine of Joy Moody is Out of Time—a woman whose fierce, unconventional love mutates into delusion, control, and finally sacrifice. In her fifties and dying of a brain tumor, she erects a mythology of time travel to protect and possess the twins she took in after accidentally killing their teenage mother, Britney White.

The persona she builds—meticulous proprietor of Joyful Suds, guardian of the “Daughters of the Future Revolution,” enemy of shadowy pursuers—lets her translate guilt into purpose and terror into routine. As the tumor erodes her memory, the boundary between the story she stole from a sci-fi trilogy and her lived past dissolves; denial becomes belief.

Her slap to Andie is the moment love curdles into harm, yet Joy’s end clarifies her core: she tries to spare her daughters a life defined by her crime, rewrites her will to keep them cared for, and ultimately chooses her own death once the fantasy collapses. She is both perpetrator and protector, a study in how trauma and illness can distort devotion until it imprisons the very people it means to save.

Cassie Moody

Cassie grows from compliant daughter to self-possessed young woman, embodying the ache of someone raised on certainty that feels safe even as it is suffocating. Quiet, affectionate, and gifted with a steady eye for pattern—seen in her sketching and the precise folding at the laundromat—she begins the novel as the child Joy wanted: dutiful, credulous, and soothed by ritual.

Her arc is not a sudden revolt but a gentle unfurling as love for Joy wrestles with dawning truth. Encounters with Omar and Shawn hint at a world where attention is simple and unweaponized, and her art becomes the language through which she processes grief and ambiguity.

Cassie’s loyalty is not naivety so much as a moral stance: she insists on the parts of Joy that were kind even while accepting the harm. By the end, Cassie is the bridge in the family—capable of forgiving without forgetting, of keeping the laundromat’s heart while repainting its walls, and of seeing a future not promised by a prophecy but built one careful choice at a time.

Andie Moody

Andie is the novel’s skeptic and spark, a young woman whose curiosity and anger become tools of emancipation. Restless, sardonic, and hungry for truth, she tests every seam in Joy’s story until the costume splits open.

Her bond with Linh offers a mirror of life outside surveillance: technology, friendship, desire, and the radical permission to ask why. The DNA kit, the hidden tablet, and the recognition of The Fortis Trilogy are forensic steps in an emotional investigation—Andie is not simply rebellious; she is a survivor mapping the exit.

Yet she is also impulsive and volatile, stealing coins, drinking too much, hiding the syringe, and carrying a private burden of shame and fear that she might be complicit in Joy’s end. With Tyler, she finds a biological thread that doesn’t erase Joy but reframes her.

Andie finishes the story unafraid to name what was abusive and unready to abandon the love that lived beside it, staking a claim to a future that is honest, messy, and hers.

Detective Sergeant Holliday Betts

Holliday is the narrative’s ballast, a detective newly promoted to Homicide whose steadiness resists the sensationalism of the case. Where others see cranks or monsters, she insists on procedure, context, and restraint.

The pink orderliness of the laundromat, the scrawled threat, the ripped note—these are data points she tests rather than dramatic cues she obeys. Her investigation fails to deliver a neat culprit not because she is incompetent but because the truth sits at the unsteady intersection of crime, illness, and love.

Holliday’s final visits to the twins show a quiet evolution from suspicion to care; she becomes a state presence capable of gentleness, validating the story’s refusal to divide people into villains and saints. She closes a non-criminal death with moral clarity: what happened was wrong, complicated, and human.

Monty Doyle

Monty is the neighbor who functions as the novel’s reluctant confessor and practical angel. A diabetic locksmith with a chessboard patience, he sees Joy and the twins without the haze of legend, choosing small acts of decency over judgment.

His role in Joy’s death—arriving with insulin to honor a promise, only to witness her take the syringe herself—places him in the crucible of mercy. He neither absolves Joy nor condemns her; he protects the girls’ inheritance and keeps her last dignity.

Monty’s goodness is mundane rather than grand, and that is the point: communities survive on people who show up, share lunch, hold secrets that would wound if shouted, and turn chaos into continuity.

Linh Tran

Linh is freedom’s first friendly face. As a tattoo artist and neighbor, she offers Andie an ethical counterculture: consent, craft, and clear boundaries.

Her studio is a civic space where questions are not punished, and her recognition of Joy’s story as fiction detonates the lie with kindness rather than cruelty. Linh’s pragmatism—setting up an email account, documenting Grant, playing the recording at the right moment—grounds the twins’ transition from isolation to community.

She is also a tender object of Andie’s attraction, an axis where curiosity about the world becomes curiosity about self. Linh models adulthood as competence without control.

Ellen Scott

Ellen, the reclusive lawyer, is the plot’s quiet lever. Initially aloof, she emerges as someone Joy once helped, repaying that debt by arranging counsel, holding the ashes, and orchestrating the traders’ collective power when Grant must be confronted.

Ellen reframes Joy’s reputation posthumously: the woman capable of terrible choices also gave time and help when asked. In Ellen’s hands, the law does what it should—protect the vulnerable, document the real, and clip the wings of a bully with receipts rather than rage.

Grant

Grant is the opportunist whose ambitions sharpen the book’s legal and moral stakes. He enters as grieving kin and quickly reveals himself as a scavenger of paperwork and property, pocketing envelopes, manipulating the twins, and rushing a cremation.

He is not the architect of the central harm, but his callousness shows how easily trauma attracts predators. The recording that exposes him is less comeuppance than diagnosis; he is a man who mistakes someone else’s life for a market.

Tyler Rodriguez

Tyler, the twins’ biological father, is a figure long shadowed by suspicion who reenters as complicated kin rather than villain. His past with Britney and the police’s earlier doubts about him are real, yet the DNA evidence and final meetings reposition him as a man trapped in the gravitational pull of a tragedy he did not control.

The McDonald’s moment—recognizing Andie’s fry-in-the-burger habit—becomes a small sacrament of kinship, proof that lineage can carry tenderness even when documents arrive late.

Britney White

Britney is the absent center, a teenage mother whose death anchors the novel’s grief. The epilogue’s revelation of the struggle that ended her life refuses to sanitize either participant: Joy’s panic becomes lethal; Britney’s instinct to fight for her babies is fierce and right.

In death, Britney becomes both wronged and revered, a reminder that the twins’ origin story is neither prophecy nor secret government program but the ordinary, devastating entanglement of poverty, youth, and fear. Her burial and recognition in the record restore to her what the lie stole—name, story, and motherhood.

Omar

Omar is a catalyst for Cassie’s awakening, a gentle flirtation that exposes the cost of Joy’s rules. He is not a soulmate or a savior; he is a boy who sees a girl drawing and treats her like a person with a life of her own.

His presence, brief but bright, marks the shift from life under surveillance to life under choice.

Shawn

Shawn, the vending-machine supplier, is a symbol of healthy mundanity. His shy interest in Cassie, uncomplicated and courteous, offers a benign alternative to the epic narratives that have governed the twins’ lives.

With him, Cassie practices ordinary beginnings—coffee, banter, a future measured in small plans rather than cosmic destinies.

Arthur Tennant

Arthur, Joy’s ex-husband, exists mostly as a wound and a warning. His departure contributes to Joy’s isolation and to the conditions in which her fantasy could take root.

He is less a character in motion than a contour in Joy’s backstory, showing how abandonment can make grand delusions feel like scaffolding rather than shackles.

Sergeant Sam Poole and Detective Leo

Poole and Leo round out the institutional frame. Poole’s reflexive suspicion of the twins contrasts with Holliday’s caution, illustrating how quick narratives can misread eccentricity as guilt.

Leo’s later visit with Holliday helps deliver closure without triumphalism, demonstrating a version of policing that can acknowledge harm, accept limits, and leave space for the living to go on.

Donna the Cat and the Kittens

Even the animals carry thematic weight. Donna’s litter is a soft continuity after rupture, the domestic counterpoint to cosmic fantasies.

The kittens’ discovery alongside the last piece of Joy’s note braids death with renewal, reminding the twins that not every ending needs a portal; sometimes it needs a bowl of milk, a fresh coat of paint, and people who will stay.

Themes

Motherhood and Moral Ambiguity

Motherhood in Joy Moody is Out of Time occupies a space that is neither purely nurturing nor wholly destructive, but something deeply human — a terrain defined by desperation, guilt, and an instinct to protect at any cost. Joy Moody’s identity is constructed entirely around her role as a mother to Cassie and Andie, though the foundation of that motherhood is built upon an unspeakable crime.

Her decision to raise Britney White’s babies after accidentally killing their mother stems from a fractured moral core: she acts both as savior and transgressor. What begins as an act of protection becomes an obsession, transforming Joy into both the guardian and the jailer of her children’s lives.

Her deception about time travel, designed initially to preserve their innocence and to give structure to her guilt, spirals into delusion as her illness progresses. This distorted motherhood exposes the tension between love and control, showing how care can mutate into confinement when rooted in fear rather than trust.

The narrative never offers a singular judgment on Joy; instead, it asks whether moral wrongs can ever coexist with genuine affection. By the end, when the truth of Britney’s death is uncovered, motherhood itself becomes the emotional crux of the novel — a paradoxical force that nurtures while it destroys, revealing that love, in its most desperate form, can be both the crime and the justification.

The Fragility of Reality and the Power of Delusion

Reality in Joy Moody is Out of Time is constantly in flux, shaped by the fragile boundaries of memory, belief, and mental deterioration. Joy’s brain tumor becomes both a physical and metaphorical device — eroding her cognitive control and blurring the line between the imagined and the real.

Her delusion of time travel is not portrayed as mere madness but as an act of emotional survival. Through that illusion, she constructs a world where her sins are justified, her daughters are extraordinary, and the chaos of her past can be rewritten as destiny.

The lies she creates begin as small comforts and expand into a fully realized parallel reality that governs her family’s existence. For the twins, growing up inside this fiction means their understanding of truth becomes fractured; Andie rebels, seeking evidence and logic, while Cassie clings to the fantasy as emotional protection.

The story thus examines how human beings manipulate perception to endure trauma. Joy’s world collapses when her internal reality can no longer sustain itself against external truth, a collapse that mirrors the human struggle to find meaning amid uncertainty.

By the end, the revelation of her lies underscores how delusion can serve as both prison and refuge, illustrating that sometimes the most powerful realities are the ones we create to survive ourselves.

Identity, Control, and the Search for Freedom

Throughout Joy Moody is Out of Time, questions of identity dominate every relationship and decision. Cassie and Andie grow up without authentic selves, their sense of who they are defined by their mother’s narrative of destiny.

Joy’s control over their upbringing — banning technology, restricting contact with the outside world, and dictating their purpose — robs them of individuality. Andie’s rebellion and Cassie’s compliance represent two opposite responses to captivity: one fights for autonomy, the other internalizes control.

As the sisters uncover the truth of their origins, their understanding of selfhood becomes an act of liberation. The revelation that they are not time travelers but the orphaned children of Britney White forces them to redefine existence outside Joy’s fantasy.

Identity, in this context, is not something given but something earned through the painful confrontation with truth. The novel suggests that control, even when motivated by love, can erase individuality and that freedom often emerges from disillusionment.

When the twins finally inherit Joyful Suds and begin rebuilding their lives, their reclamation of the laundromat becomes symbolic — a reclaiming of space, agency, and history. In finding out who they are, they also decide who they will become, marking a shift from inherited falsehood to self-created meaning.

Trauma, Guilt, and the Weight of the Past

Every character in Joy Moody is Out of Time carries the residue of unprocessed trauma — from Joy’s guilt over Britney’s death to the twins’ confusion born from years of deceit. The past functions not as a distant memory but as an omnipresent force dictating their actions and emotional states.

Joy’s creation of an elaborate fiction is her way of burying the unbearable, transforming guilt into mythology. Yet the story refuses to let the past remain buried: Britney’s body, hidden beneath the shed, becomes the literal manifestation of buried trauma, surfacing only when truth demands confrontation.

Detective Holliday Betts’s investigation serves as the mechanism through which this buried past is unearthed, both legally and emotionally. The revelation that Joy’s supposed “time travel” story was rooted in an act of violence reframes every earlier moment of affection, showing how guilt distorts love.

Even after Joy’s death, her daughters and friends must navigate the emotional debris she leaves behind, learning to live within the shadow of her choices. The novel ultimately portrays trauma not as a single wound but as a generational legacy — something inherited, endured, and, if confronted honestly, eventually transformed into understanding.

Redemption, Forgiveness, and the Persistence of Love

Despite its darkness, Joy Moody is Out of Time closes on an unexpectedly tender note, suggesting that redemption is not achieved through erasing sin but through understanding it. The twins’ gradual forgiveness of their mother — even after uncovering her lies and crimes — reflects the story’s central conviction that love persists beyond truth.

Joy’s final acts, including her confession to Monty and her decision to end her life, are presented as gestures of remorse and release. Her death allows the possibility of reconciliation between past and present, between lie and love.

When Cassie and Andie scatter Joy’s ashes at the beach, it is not a celebration of forgiveness but an acknowledgment of complexity — the acceptance that love and harm often exist in the same gesture. Redemption here is collective rather than individual: Monty’s loyalty, Linh’s compassion, Ellen’s support, and the community’s restoration of the laundromat all contribute to healing.

The closing image of the sisters rebuilding Joyful Suds into a place of renewal signifies that love, though flawed and painful, remains the only enduring force capable of transforming guilt into grace. Through this quiet resolution, the novel affirms that redemption is not about forgetting but about choosing to live truthfully after everything false has fallen away.