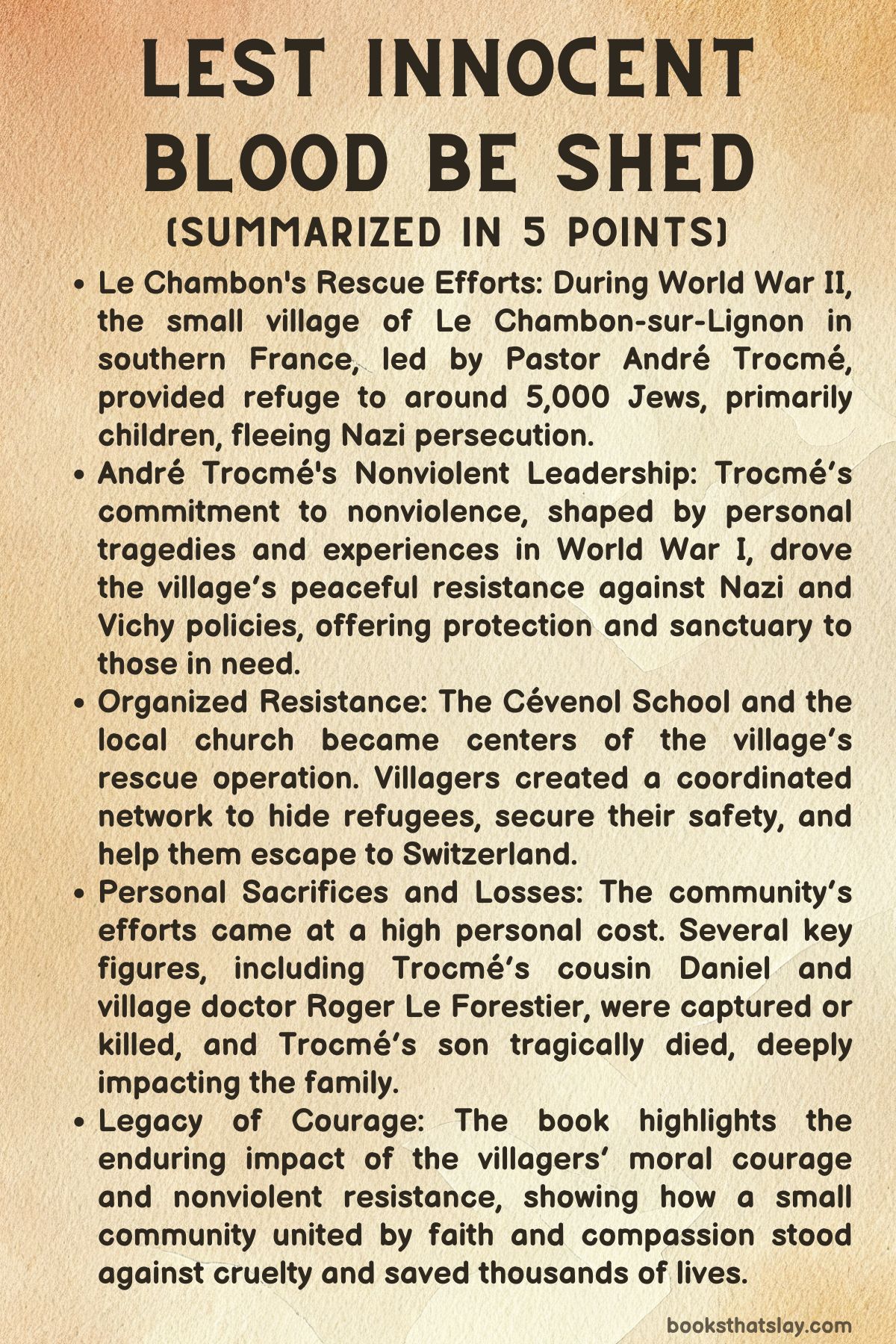

Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed Summary and Analysis

Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed by Philip Hallie tells the remarkable story of the village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon in France, where the residents, led by Pastor André Trocmé, saved thousands of Jewish people from Nazi persecution during World War II. Hallie, a philosopher and scholar of ethics, uses this historical account to explore human kindness, moral courage, and the strength of nonviolent resistance.

The book reveals how a small community, guided by deep convictions of faith and compassion, stood against cruelty, offering sanctuary to those facing unimaginable danger during one of history’s darkest periods.

Summary

In Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed, Philip Hallie explores the inspiring story of Le Chambon, a small French village that, during World War II, became a haven for Jews fleeing the Nazis.

Central to this extraordinary tale is the figure of André Trocmé, the village’s Protestant pastor, whose commitment to nonviolence was shaped by the traumas of his youth. Trocmé, whose lineage traced back to Huguenots, was deeply influenced by the sudden death of his mother and his experiences with German soldiers during World War I.

These formative events instilled in him a profound aversion to violence, which would later guide his leadership during the Nazi occupation.

Trocmé studied in France and later in the United States, where he met his wife, Magda. Together, they returned to France and eventually moved to Le Chambon, where Trocmé took on the role of pastor.

Their early efforts to rejuvenate the village included founding the Cévenol School, which not only provided education but was also rooted in pacifist ideals. Though the school initially faced challenges, it eventually became a centerpiece of the community, drawing support from the villagers, who shared in its mission of nonviolence.

As Europe became engulfed in war and France fell under Nazi occupation, Le Chambon quietly transformed into a refuge for those fleeing persecution, especially Jews.

In 1940, after the signing of the armistice that divided France into the German-occupied north and the Vichy-controlled south, Trocmé and the villagers began resisting the discriminatory policies of the Vichy regime.

At first, their opposition took subtle forms, like the Cévenol students’ refusal to salute the fascist flag and the village temple’s silence on Pétain’s national holiday. These acts, though seemingly small, grew into a more organized effort to hide and protect Jews.

By the summer of 1942, when Jews across France were being rounded up and sent to places like the Vel d’Hiv in Paris or deported to concentration camps, Le Chambon’s defiance became more pronounced.

When authorities demanded a list of Jewish residents, Trocmé refused, and the village rallied to shield the refugees.

Their resistance grew into a large-scale effort, with many villagers participating in hiding Jews, particularly children, and helping them escape to neutral Switzerland.

Despite numerous raids and searches by the authorities, Le Chambon’s network remained largely undetected, and they succeeded in saving approximately 5,000 Jews. However, not all efforts ended without loss.

Trocmé’s cousin Daniel, who ran a shelter in the village, was captured along with the children he protected and later perished in the camps.

Another village doctor, Roger Le Forestier, met a tragic end, shot by the Gestapo despite attempts to save him. Closer to home, the deaths of Trocmé’s son Jean-Pierre and a young local girl, Manou, dealt severe emotional blows to the Trocmé family.

Even in the face of such hardship, Trocmé continued to advocate for nonviolence after the war, and the Cévenol School survived, staying true to its founding principles.

Hallie’s narrative, shaped by his own encounters with the Trocmé family and the people of Le Chambon, serves as both a testament to their courage and a meditation on the power of moral conviction in the face of brutality.

Analysis and Themes

The Intersection of Moral Integrity, Religious Conviction, and Nonviolent Resistance

One of the central themes in Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed is the interplay between moral integrity, religious conviction, and nonviolent resistance. The story of André Trocmé and the village of Le Chambon illuminates how deeply held religious beliefs—particularly Protestantism with its historical roots in resistance, as seen in the Huguenot heritage—can translate into a moral commitment to nonviolent action.

Trocmé’s experiences during World War I, combined with his personal loss and spiritual reflections, forge a theology where nonviolence is not just a tactic but a moral imperative.

This commitment is mirrored in the village’s collective response to the horrors of the Nazi occupation and the Vichy government’s complicity in the persecution of Jews.

Trocmé’s leadership challenges the simplistic idea of passive pacifism, instead portraying nonviolent resistance as an active, courageous, and deeply moral stance. Le Chambon becomes a site of quiet, yet powerful, defiance rooted in ethical and spiritual values, revealing that moral integrity can fuel extraordinary acts of resistance even in the face of seemingly insurmountable brutality.

The Fragility of Faith Under the Weight of Human Tragedy

Hallie’s work also deeply explores the theme of the fragility of faith, particularly as it is tested by immense human suffering and loss.

While the overarching narrative celebrates the moral triumphs of the villagers, it does not shy away from depicting the psychological and spiritual toll that such relentless resistance takes on individuals, especially the Trocmé family.

André Trocmé’s steadfast faith in nonviolence and human dignity is severely shaken after the death of his son Jean-Pierre, whose accidental hanging drives the pastor and his wife into a profound crisis of faith.

The fragility of religious conviction under the weight of personal and communal tragedy is a recurring element, not just in Trocmé’s personal journey, but in the story of Le Chambon as a whole.

The village’s commitment to sheltering Jewish refugees was not without loss, as seen with the deaths of Daniel Trocmé, Roger Le Forestier, and others who fell victim to Nazi persecution.

These tragedies expose the vulnerability of even the strongest faith when confronted by seemingly senseless deaths, and the narrative underscores that moral goodness and faith are not immune to collapse under extreme pressure.

Ethical Ambiguity and the Boundaries of Goodness in the Midst of War

Another major theme in the book is the ethical ambiguity of resistance and survival in a time of war. The villagers’ actions, while grounded in moral and religious convictions, take place in a context fraught with risk, fear, and uncertainty.

Hallie’s portrayal of Le Chambon challenges simplistic notions of heroism, presenting the complexity of ethical decision-making during the Nazi occupation. The villagers, led by Trocmé, constantly grapple with the boundaries of legality and morality, often engaging in deception and subversion to protect their Jewish guests.

This theme is exemplified in Trocmé’s refusal to provide names to the Vichy police and in the covert actions of his wife Magda and other villagers who worked tirelessly to conceal refugees and ensure their safe passage.

While their actions were undoubtedly ‘good,’ they also operated in a morally ambiguous space where they had to weigh the consequences of their decisions—not just for the refugees, but for the safety of the entire village.

The ethical boundaries between resistance and complicity blur in moments of fear, as villagers risk their lives in defiance of both the Nazi regime and their own government’s demands.

Collective Action and the Ethics of Shared Responsibility in the Context of Systematic Injustice

A prominent theme that runs throughout Hallie’s narrative is the idea of collective action and the ethics of shared responsibility in the face of systematic injustice. The rescue efforts in Le Chambon were not the result of a single individual’s heroism but a deeply communal effort where each villager played a role, from harboring refugees to creating escape routes to neutral Switzerland.

Hallie emphasizes how the collective ethos of the village—rooted in Trocmé’s teachings but extending far beyond his immediate influence—created a moral community that valued human life above all else.

This communal ethic stands in stark contrast to the bureaucratic and systematic dehumanization represented by the Vichy regime and the Nazi occupiers.

In Le Chambon, shared responsibility for the well-being of others becomes an ethical norm, challenging the bystander effect that often accompanies large-scale atrocities.

The narrative showcases how, in the face of genocide, individual acts of kindness and courage are amplified through collective solidarity, forming a bulwark against moral apathy and complicity.

The Tension Between Ethical Universalism and Cultural Particularism in Resistance Movements

Hallie’s exploration of Le Chambon also introduces the tension between ethical universalism and cultural particularism, a theme that becomes particularly evident in the intersection of religious, cultural, and ethical values.

The villagers’ commitment to saving Jews stems from deeply held religious convictions about the sanctity of life and the moral duty to protect the vulnerable.

However, the narrative also highlights how this moral imperative intersects with their particular cultural identity as Huguenots, a Protestant minority historically persecuted in France.

This cultural particularism fuels a deep empathy for the persecuted Jews, as the villagers see echoes of their own history of suffering and survival.

At the same time, the ethical universalism of their actions—saving lives regardless of nationality, ethnicity, or religion—extends their local identity into a broader moral framework.

This tension between the local and the universal creates a rich thematic complexity in the book, where cultural particularism becomes the foundation for universal ethical principles, suggesting that even the most localized identity can have far-reaching moral implications in times of crisis.

The Role of Moral Agency and the Limits of Bureaucratic Power

A final theme worth noting is the contrast between moral agency and the limits of bureaucratic power, which plays out in the interactions between the villagers and the Vichy authorities.

Hallie carefully dissects the notion that oppressive systems—whether the Nazi regime or the Vichy government—rely on a dehumanizing bureaucracy that strips individuals of moral agency.

The villagers of Le Chambon, however, reclaim that agency through their conscious and deliberate acts of resistance. Trocmé’s refusal to submit to bureaucratic orders, whether it is naming Jewish refugees or endorsing fascist policies, illustrates the power of individual and collective moral agency against the facelessness of systemic oppression.

This theme is further emphasized in the actions of Quaker activist Burns Chalmers, who works alongside the Trocmés to establish a rescue network, challenging the bureaucratic structures that sought to categorize and eliminate human beings based on ethnicity or religion.

Through these characters, Hallie reveals the inherent limitations of bureaucratic power when it is met with the moral courage of individuals and communities determined to act according to their ethical beliefs.