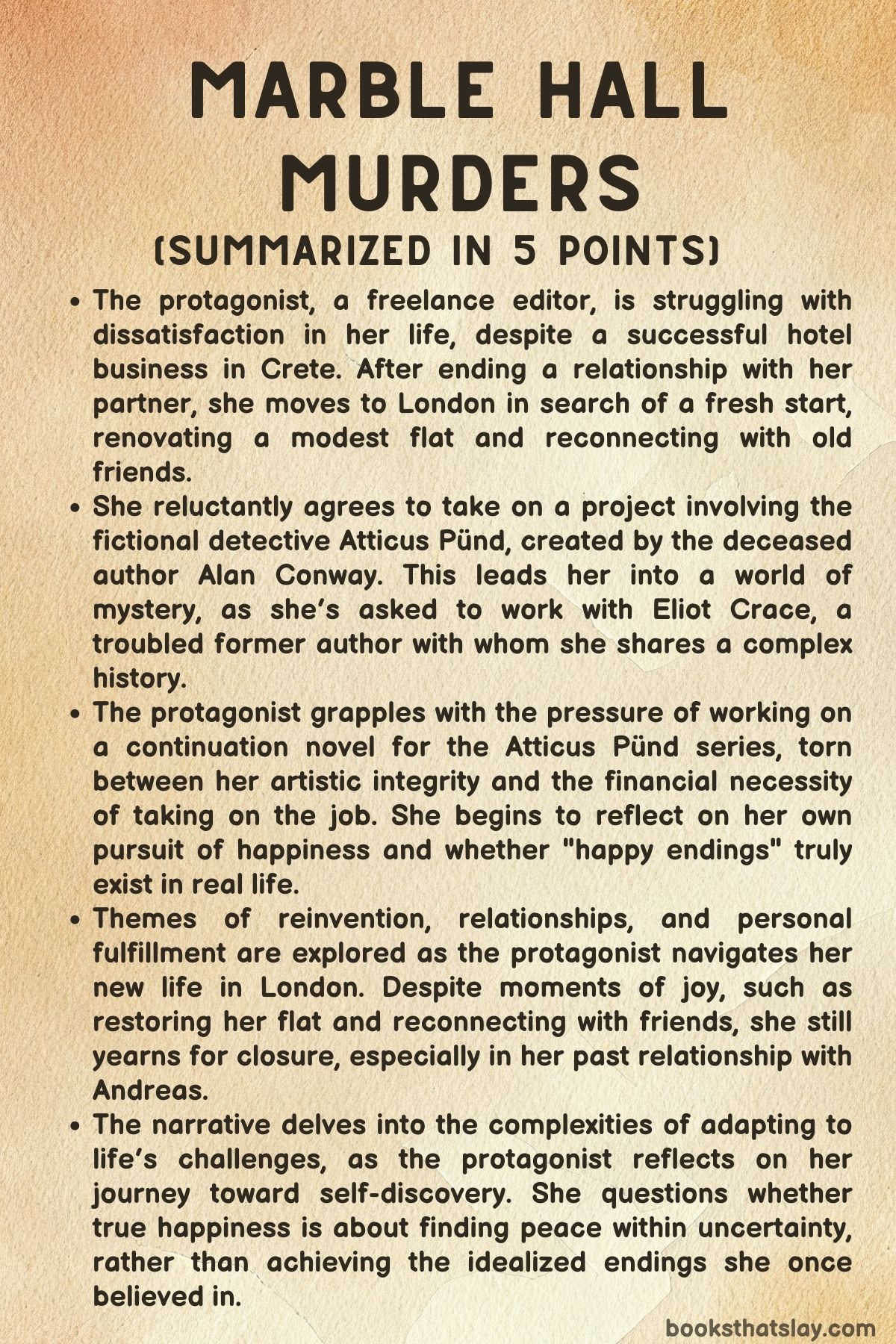

Marble Hall Murders Summary, Characters and Themes

Marble Hall Murders by Anthony Horowitz is a layered mystery that blends a continuation of the Atticus Pünd detective novels with a modern publishing intrigue.

At its heart is Susan Ryeland, an editor who becomes entangled in a dangerous web while working on a new manuscript. The story moves between Susan’s present-day struggles with authors, estates, and hidden family secrets, and the unfolding fictional mystery of Atticus Pünd’s final case. With word games, anagrams, and stories that mirror real life, the novel explores themes of legacy, deception, and the consequences of mixing truth with fiction.

Summary

Susan Ryeland returns to London after an unsatisfying life in Crete with her partner Andreas. Trying to restart her career, she reconnects with Causton Books, where her former colleague Michael Flynn commissions her to edit a new Atticus Pünd novel, despite the original author Alan Conway being dead.

The new writer is Eliot Crace, grandson of famed children’s author Miriam Crace, whose legacy looms heavily over her family. Susan is hesitant but takes the assignment, aware of how Conway’s mixing of fiction and real life once nearly cost her own life.

The manuscript, titled Pünd’s Last Case, mirrors Eliot’s real family history. In the fictional story, Atticus Pünd investigates the suspicious death of Lady Margaret Chalfont at her French estate, Chateau Belmar.

Suspicion falls on her American husband Elmer Waysmith, but Pünd gradually discovers the family colluded to frame Elmer. The true killer is Robert Waysmith, Margaret’s stepson, who murdered her with poison and later killed Alice Carling, a secretary who knew too much.

Robert’s bitterness toward his father and thwarted artistic ambitions drive him to murder, with his siblings as accomplices.

As Susan edits the book, she notices how closely characters and events echo Eliot’s own life. Marble Hall, Miriam’s grand estate, becomes the basis for Chateau Belmar, and Eliot infuses his resentment toward Miriam into the narrative.

Eliot admits to Susan that he and his siblings once plotted to kill Miriam, though she supposedly died of natural causes. He hints Miriam was actually murdered, a suspicion he claims to embed as clues within the manuscript.

Susan meets various members of the Crace family. Jonathan, who runs the estate, is protective of Miriam’s reputation and is negotiating a Netflix deal for the Little People series.

Roland, Eliot’s brother, quietly admits Miriam was cruel and controlling, though he insists she died naturally. Julia, their sister, shares memories of abuse but is resigned to silence due to legal agreements.

Frederick, Miriam’s adopted son, praises her but warns Susan not to trust Eliot. Conflicting accounts leave Susan uncertain whether Miriam was revered or reviled.

Meanwhile, Eliot spirals. He is late to meetings, volatile, and abusive toward his wife Gillian, who is secretly pregnant with another man’s child—possibly Roland’s.

Susan’s concerns deepen when Eliot gives a disastrous interview, publicly accusing Miriam of being murdered. At a family party meant to celebrate Miriam’s legacy, Eliot drunkenly shouts that his forthcoming book will reveal the truth.

Soon after, he is killed in a hit-and-run.

The police suspect Susan, citing her argument with Eliot, her attendance at the party, and fabricated evidence linking her car to the crime. Detective Inspector Ian Blakeney, however, believes she is being framed.

He shares Eliot’s notes with her, which reveal hidden anagrams, character parallels, and unresolved mysteries. The two begin working together, professionally and personally, to uncover the truth.

Susan’s flat is later broken into, her belongings destroyed, and her cat stabbed, though it survives. She realizes Elaine Clover, widow of Alan’s killer Charles, orchestrated the attack, planted evidence, and framed her for Eliot’s murder.

Elaine, seeking revenge, even attacks Susan with a knife before Blakeney intervenes and arrests her.

Attention then shifts back to Miriam’s death. Susan, with Blakeney’s support, arranges a final meeting at Marble Hall.

There, she reveals that Miriam’s supposed adopted son Frederick is actually her biological child, fathered by her chauffeur Bruno. He inherited Miriam’s traits of color-blindness and left-handedness, proving the connection.

Miriam, who had banished Bruno, left Frederick bitter. Inspired by Eliot’s childhood games with poison, Frederick killed Miriam using arsenic from Kenneth Crace’s taxidermy collection.

Years later, fearing Eliot’s claims might expose him, he also killed Eliot.

Frederick confesses, explaining that while killing Miriam felt justified after her cruelty, killing Eliot was necessary to protect himself. He is arrested, bringing closure to both murders.

A year later, Susan has rebuilt her life. She founds Nine Lives Books, publishes Eliot and Blakeney’s completed version of Pünd’s Last Case, and also releases a suppressed biography of Miriam, exposing her true character.

She and Blakeney, now lovers, celebrate the success of her new publishing venture at a book launch. Susan finally feels content, having reclaimed control of her career and her happiness, while ensuring Eliot’s work—and the truth about Miriam—are not lost.

Characters

Susan Ryeland

Susan Ryeland is the central character of Marble Hall Murders, a seasoned editor who is both intelligent and skeptical, yet often pulled into dangerous situations through her professional work. Having survived the chaos of Alan Conway’s novels and his death, she carries both physical and emotional scars, including her damaged eyesight and a lingering mistrust of authors who blur fiction with reality.

Susan’s sharp mind allows her to see through the manipulations within Eliot’s manuscript, and her instincts drive her to uncover the truth behind Miriam Crace’s life and death. Despite her weariness, she continues to chase answers, which puts her in conflict with powerful figures.

Her moral compass remains strong, and her determination to survive, protect her reputation, and pursue justice makes her one of the most resilient characters in the novel. By the end, Susan emerges not just as an editor but as a survivor who reclaims her power by starting her own publishing company, Nine Lives Books, symbolizing a new independence and fulfillment.

Eliot Crace

Eliot Crace is a deeply troubled figure, both a writer struggling with failure and a grandson haunted by the oppressive legacy of Miriam Crace. His resentment toward Miriam, coupled with years of neglect and substance abuse, shapes much of his identity.

His attempt to write Pünd’s Last Case reflects his need for both revenge and recognition, blending his family’s history with fiction in a way that destabilizes him further. Eliot’s relationship with Susan is erratic; he seeks her validation while also pushing her away.

His marriage to Gillian is fraught with violence, jealousy, and betrayal, particularly after her pregnancy by another man. Eliot’s public breakdowns, including his drunken interview and outburst at the family party, show a man consumed by bitterness and self-destruction.

Ultimately, his death cuts short any redemption he might have found, but his manuscript ensures his voice lingers, exposing both family secrets and his obsession with Miriam.

Miriam Crace

Though deceased long before the events of Marble Hall Murders, Miriam Crace dominates the novel as both a literary icon and a tyrant within her family. To the public, she is remembered as the beloved creator of the Little People series, but within the Crace family, memories of her cruelty, racism, and control persist.

Accounts of her vary—Jonathan idolizes her, Frederick defends her, while Eliot, Roland, and Julia recall her as abusive and manipulative. Miriam demanded absolute loyalty, enforced silence with legal contracts, and belittled her grandchildren.

Her death, long assumed to be natural, is eventually revealed to be a murder. Yet even in death, Miriam exerts influence: her estate continues to profit, her reputation is fiercely defended, and the secrets she left behind shape the destinies of those around her.

Miriam embodies the tension between public legacy and private reality, a theme that drives the mystery of the novel.

Frederick Turner

Frederick Turner, Miriam’s adopted son, is eventually revealed to be her biological child, fathered by her chauffeur, Bruno. Outwardly quiet and loyal, Frederick carries the weight of rejection, secrecy, and illegitimacy.

His disabilities, acquired in a car accident, and his reliance on the Crace estate for his livelihood mask a deep resentment. When Susan meets him, he initially appears mild-mannered and grateful to Miriam for saving him from an orphanage.

Yet his eventual confession of murdering Miriam reveals a darker truth: his actions were driven by vengeance for both himself and his father, whom Miriam cast aside. Frederick also kills Eliot to protect the secret of Miriam’s murder.

His character highlights the destructive power of buried family secrets, and while his motive for killing Miriam is portrayed as understandable, his decision to murder Eliot cements him as a tragic villain, destroyed by the very legacy he tried to escape.

Jonathan Crace

Jonathan, Miriam’s son and executor of her estate, is portrayed as controlling, ambitious, and desperate to protect Miriam’s image. He oversees the Crace Estate, manages the Marble Hall museum, and aggressively pursues commercial opportunities like the Netflix adaptation of the Little People series.

To him, Miriam represents perfection, and he refuses to acknowledge her cruelty. Jonathan is more concerned with wealth and reputation than with truth, even bribing Dr.

Lambert to falsify Miriam’s cause of death. His confrontations with Susan show his hostility toward anyone who threatens the carefully constructed image of his mother.

Jonathan’s denial and corruption reveal how deeply Miriam’s dominance continues to shape the family, even after her death. He represents the institutional power that keeps abusive legacies hidden under a veil of cultural reverence.

Roland Crace

Roland is perhaps the most honest of Miriam’s grandchildren, acknowledging her cruelty and openly sharing with Susan his true feelings about their upbringing. Unlike Jonathan, he separates Miriam’s literary legacy from her personal failings, claiming that while she was a dreadful person, her work has cultural value.

Roland’s position within the family is complicated; though he once joined Eliot and Julia in plotting against Miriam as children, he later works for the Crace Estate, earning Eliot’s resentment. His affair with Gillian further damages his relationship with Eliot, adding a personal betrayal to their lifelong rivalry.

Roland embodies the difficulty of reconciling with a painful past, balancing survival within the estate with the need to acknowledge truth.

Julia Crace

Julia, Eliot and Roland’s sister, carries the scars of Miriam’s cruelty. Bullied for her weight and appearance, Julia grew up in an oppressive household where even her parents were too fearful to protect her from Miriam.

Despite this, Julia finds some healing through therapy and maintains close bonds with Roland, whom she credits with supporting her during her darkest times. At the family party, she is one of the few who admits openly that Miriam was abusive, though she, too, is bound by legal agreements preventing her from speaking out publicly.

Julia’s resilience contrasts with Eliot’s destructive path, as she learns to cope and move forward rather than let Miriam’s cruelty consume her entirely.

Elaine Clover

Elaine Clover is one of the most dangerous figures in Susan’s life. The widow of Charles Clover, Alan Conway’s killer, she initially appears sympathetic, presenting herself as a supportive friend.

However, it becomes clear that Elaine is consumed by bitterness over her husband’s imprisonment, which she blames on Susan. Manipulative and vengeful, she orchestrates a campaign to frame Susan for Eliot’s murder, breaking into her flat, destroying her belongings, and even stabbing Susan’s cat.

Elaine embodies the dangers of misplaced loyalty, consumed by the belief that Charles was a good man wronged by circumstance. Her violent breakdown, where she nearly kills Susan, reveals how grief and anger can corrode morality.

Elaine’s arc serves as a reminder of how unresolved pain can turn into cruelty and obsession.

Ian Blakeney

Detective Inspector Ian Blakeney is both an ally and eventual partner to Susan. Unlike his colleague Wardlaw, who is suspicious and hostile, Blakeney treats Susan with respect and trusts her intelligence.

A lifelong mystery enthusiast and admirer of Atticus Pünd, he appreciates Susan’s insight into Eliot’s manuscript and encourages her to work with him. His personal story of loss—particularly his wife’s death from cancer—makes him empathetic and thoughtful, qualities that deepen his bond with Susan.

By helping expose Frederick as both Miriam’s and Eliot’s murderer, Blakeney proves himself to be a capable investigator. His decision to write under the pseudonym Ian Black and publish with Susan represents both a personal renewal and the start of a new chapter in his life.

Gillian Crace

Gillian, Eliot’s wife, is caught in a difficult and destructive marriage. Initially introduced as a supportive partner, it soon becomes clear that she is both a victim of Eliot’s violence and an individual carrying her own secrets.

Her pregnancy by another man—implied to be Roland—fuels Eliot’s rage, but Gillian remains quiet and evasive, unwilling to expose the truth. Susan notices that Gillian resembles Alice Carling in Eliot’s manuscript, suggesting that Eliot blurred his personal betrayals into his fiction.

Gillian’s character reflects the damage inflicted by toxic relationships, where fear, secrecy, and shame perpetuate cycles of abuse. She is one of the more tragic figures, trapped between her loyalty to Eliot and her need for independence.

Themes

Legacy and Inheritance

The idea of legacy drives much of Marble Hall Murders, both within the fictional manuscript and in the lives of the Crace family. Miriam Crace’s influence lingers long after her death, shaping not only the family’s public reputation but also their personal relationships and sense of identity.

For Jonathan, the estate and the Little People series are sacred, symbols of stability and continuity, and he is determined to protect them even at the cost of silencing truth. Roland, by contrast, recognizes the cruelty Miriam inflicted, yet he separates her work from her character, preserving her reputation for pragmatic reasons.

Julia’s life is marked by shame and trauma tied directly to Miriam’s abuse, leaving her silenced under legal contracts. Eliot’s struggle to emerge as a writer is inseparable from his resentment of Miriam and the way her shadow continues to dominate his life.

Even Susan, an outsider, becomes entangled in the family’s legacy through her role as Eliot’s editor and investigator. Within the Atticus Pünd narrative, legacy appears in Margaret’s will and in the inheritance disputes that motivate much of the conflict.

Elmer is cast as an outsider in the family due to his nationality and social class, while Margaret’s children cling to her wealth as a form of validation. Both the real and fictional families demonstrate how inheritance is not just material wealth but also emotional and psychological baggage.

The idea of what is passed down—whether financial power, reputation, or generational trauma—becomes central to the mystery and to the destruction it causes.

Truth and Fiction

The blurring of fact and fiction lies at the heart of Marble Hall Murders, with Eliot’s manuscript serving as both a continuation of Alan Conway’s work and a distorted mirror of his own family history. Characters in the novel mirror real people: Margaret is modeled on Miriam, Cedric on Eliot, and Robert on Roland.

Eliot uses fiction not simply as art but as a weapon, embedding accusations and suspicions into his narrative. His claims that Miriam was murdered, and his hints about her cruelty, become less a story and more a disguised testimony against his family.

For Susan, who has lived through Alan Conway’s dangerous blending of fact and fiction, the manuscript is troubling; she recognizes how dangerous it can be when novels echo reality too closely. Alan’s games with names and anagrams once led to murder in her past, and Eliot’s similar approach threatens to repeat history.

Beyond Eliot, fiction itself becomes a contested arena. The Crace estate insists on Miriam’s saintly image, using contracts and censorship to control narratives about her life.

Susan, through her editorial role, must decide whether stories should preserve myths or reveal uncomfortable truths. By the end, the manuscript becomes both a key to unlocking a real murder and a symbol of how storytelling can preserve reality more honestly than the carefully curated histories of powerful families.

The tension between fiction as invention and fiction as revelation drives the mystery, questioning who has the right to control a narrative and how truth often hides in plain sight under the guise of story.

Power and Control

Control manifests in relationships, careers, and narratives throughout Marble Hall Murders, demonstrating how power is exerted both openly and subtly. Miriam exemplifies domination in her family, binding relatives through financial dependence, NDAs, and psychological manipulation.

Her cruelty toward Julia and indifference toward Eliot shaped their adult lives, while her influence over Jonathan continues even after her death. Jonathan assumes her mantle, controlling the estate and suppressing dissent to protect both reputation and profit.

This control extends into the publishing world, where Michael Flynn allies with the estate for financial gain, leaving Susan powerless and marginalized in her career. Within the fictional Pünd story, control is reflected in Margaret’s marriage to Elmer, where power dynamics between old aristocracy and new wealth are contested, and later in Robert’s manipulation of his siblings to frame his father for murder.

On a personal level, Eliot’s abusive behavior toward Gillian reveals how control plays out in domestic spaces, echoing the larger structures of coercion in the Crace family. Susan’s own life has been marked by battles against controlling figures, first Alan Conway and later Elaine, who tries to destroy her reputation and safety.

Even Charles, from his prison cell, seeks to manipulate Susan psychologically by reminding her of her career’s downfall. Ultimately, the theme of control underscores how characters use authority, money, and fear to bend others to their will, and how truth and justice require dismantling these forms of domination.

Susan’s victory in the end is not just survival but reclaiming power by creating her own publishing house, free from the manipulations of others.

Family Secrets and Betrayal

Secrets hidden within families fuel both the fictional and real mysteries in Marble Hall Murders. Miriam’s family is riddled with concealed truths: Frederick’s true parentage, Julia’s silenced trauma, Roland’s uneasy compromises, and Jonathan’s willingness to bribe Lambert to protect their image.

Eliot’s resentment stems from being forced to live in a household where appearances masked a toxic reality. His decision to turn family secrets into narrative devices is itself an act of betrayal, exposing private wounds for public consumption.

Yet the greatest betrayal comes from within the family itself: Frederick, revealed to be Miriam’s illegitimate son, murders both Miriam and Eliot. His actions are framed by resentment at being hidden and disowned, his life shaped by secrets he had no say in.

The fictional narrative mirrors this dynamic, with Robert Waysmith conspiring to frame his own father for murder out of deep-seated resentment and a sense of betrayal over a lost artistic life. Within Susan’s world, betrayal surfaces repeatedly—Elaine’s duplicity in pretending to be supportive while framing Susan for Eliot’s death, Michael’s betrayal of her trust by siding with the Crace estate, and Gillian’s betrayal of Eliot through her affair.

These betrayals highlight the fragility of trust and the destructive potential of hidden truths. Families in the novel are less sources of comfort than cages of obligation, resentment, and manipulation, where secrecy corrodes relationships and betrayal becomes inevitable.

In the end, the exposure of these secrets leads to the collapse of the estate’s carefully crafted image, proving that truth cannot be permanently suppressed.

Justice and Morality

The search for justice in Marble Hall Murders is complicated by questions of morality, legality, and personal perspective. Atticus Pünd, within the manuscript, represents rational justice, piecing together clues to expose Robert and his accomplices.

Yet even Pünd acknowledges that justice is imperfect—Elmer, guilty of dealing in stolen art, escapes accountability for his crimes. In the real world, Susan’s pursuit of justice is fraught with obstacles.

The police initially misinterpret evidence, focusing on her as the main suspect. Wardlaw embodies the dangers of prejudice and shortcuts in justice, pressing Susan to confess despite the lack of true evidence.

In contrast, Blakeney represents a more balanced view of justice, combining professional duty with empathy, ultimately trusting Susan’s instincts. The moral question of Miriam’s murder further complicates matters.

Frederick’s act of killing her is presented as both understandable and wrong: understandable because Miriam was cruel, controlling, and destructive, but wrong because taking her life placed Frederick outside the bounds of law. His subsequent murder of Eliot is portrayed as far less ambiguous, an act of silencing that destroys any moral justification.

Justice also comes in symbolic forms. Susan, who was once disempowered in her career and life, achieves a form of personal justice by establishing her own publishing house and exposing the truth about Miriam through publication.

The novel suggests that while legal justice may falter or be incomplete, moral justice can still be achieved through truth-telling, survival, and the restoration of personal agency. Justice, therefore, is not confined to courts but found in reclaiming dignity and speaking against falsehood.