Mirror Me Summary, Characters and Themes

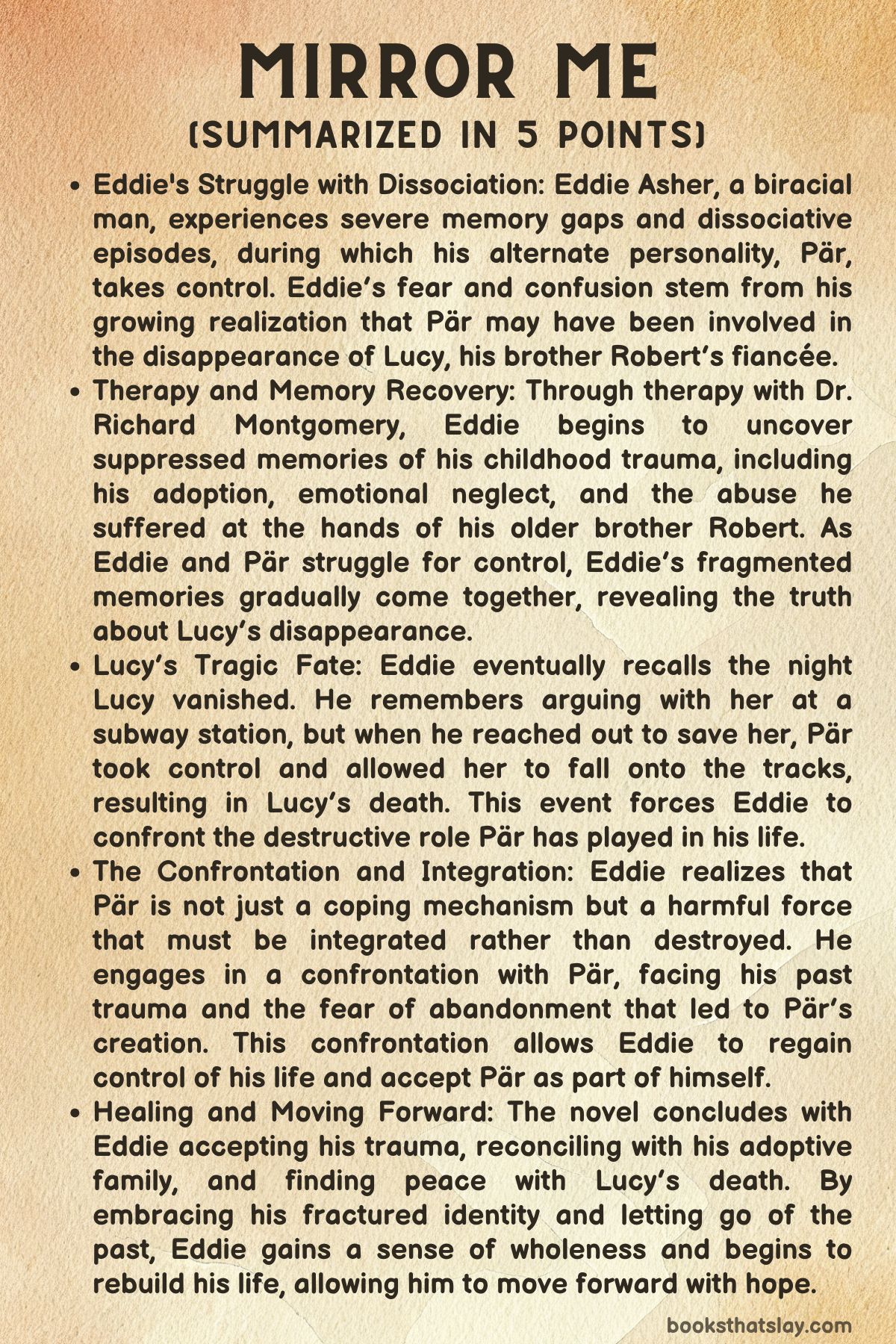

Mirror Me by Lisa Williamson Rosenberg is a psychological novel that examines the fragile nature of identity, memory, and self through the experiences of Eddie Asher, a biracial adoptee with dissociative identity disorder (DID). Told through shifting perspectives—including Eddie, his alternate personality Pär, and his long-lost twin—the narrative charts Eddie’s journey through trauma, fragmented memories, emotional entanglements, and the search for wholeness.

As Eddie confronts the mysteries of his past, his relationships, and the secrets embedded in his fractured psyche, the novel lays bare the intersections of race, family, mental illness, and the human drive to be seen and known in one’s entirety.

Summary

Eddie Asher, a young biracial man, is introduced in a state of mental disarray, running through New York City in terror, haunted by the belief that he may have pushed his lover Lucy onto subway tracks. This moment signals the precariousness of his mental state, marked by the presence of a dissociative identity—Pär—who, once protective, has become a dangerous and autonomous force.

Eddie’s reality begins to blur, his sense of self crumbling as memories fragment and hallucinations mount. His panic culminates in a suicide attempt, interrupted by Pär, who paradoxically fights to preserve their shared life.

Eddie checks into the Hudson Valley Psychiatric Hospital seeking clarity. There, he begins therapy with Dr.

Richard Montgomery, a psychiatrist whose book on identity disorders offers Eddie hope. However, Montgomery’s clinical interest becomes a stage for psychological conflict.

Pär introduces himself directly to Montgomery and claims the name “Pär”—originally given to Eddie at birth. The name’s appropriation is not only a symbolic erasure but also a declaration of dominance, as Pär begins asserting himself with increasing control.

Eddie, meanwhile, is left destabilized, unsure whether he can ever fully reclaim his own identity.

Through therapy and journaling, Eddie starts recovering memories from his childhood: the trauma of being adopted by a white family, the emotional confusion of being biracial in a context that denied race, and his fraught relationship with his older adoptive brother Robert. These early experiences are central to Pär’s emergence, particularly a traumatic separation from Eddie’s Swedish birth mother that first fractured his sense of self.

Pär evolved as a coping mechanism in infancy, and over time, assumed greater control, often surfacing during moments of high stress, especially around intimacy and trauma.

Montgomery’s sessions challenge Eddie’s memories. Events Eddie believed were comforting—like Robert rescuing him from a bathtub as a child—are cast into doubt.

Montgomery suggests Robert may have inflicted trauma, triggering Eddie’s first dissociative split. This theory is reinforced by Pär’s recollections, which often contradict Eddie’s and seem disturbingly accurate.

Pär’s voice grows more confident, even malevolent, recounting his manipulation of Eddie’s relationships and his desire to preserve his own existence at any cost.

One of the most emotionally charged elements of Eddie’s journey is his complex relationship with Lucy Wynter, a mixed-race woman whose own struggle with identity parallels his own. Eddie believes he met Lucy in adulthood, but Pär remembers her from childhood, raising unsettling questions about Eddie’s blocked memories.

Their relationship is intensely close, though never romantic in a traditional sense. They share a deep emotional intimacy and connection, but their bond defies easy categorization.

Lucy remains tied to Robert, exacerbating Eddie’s emotional conflict.

The Wynter family becomes a surrogate home for Eddie, particularly through his relationship with Tyrone Wynter, Lucy’s father. Tyrone, ill with cancer, confides in Eddie during hospital visits, sharing poetry and memories.

Eddie becomes a trusted companion, filling a role that resembles a son. Yet this role is always shadowed by the absent figure of Andy Lindberg, a young man Tyrone had mentored.

The family and even Tyrone sometimes mistake Eddie for Andy, further complicating his already fragile sense of identity. Eddie delivers a eulogy at Tyrone’s funeral—words that are not his own but those of another consciousness, “Mirror Eddie,” or “The Other,” a darker alter who seizes control during critical moments.

As the narrative progresses, Eddie’s psychological unraveling deepens. He loses time, becomes consumed with guilt over Lucy’s disappearance, and is overwhelmed by visual hallucinations and sensory flashbacks.

Pär manipulates fellow patient Ray Gilooley to draw a haunting image of Lucy tied to train tracks, stirring Eddie’s repressed trauma. Eddie’s episodes become more frequent, his grip on reality more tenuous.

The revelation of Lucy’s relationship with her former lover Carlo devastates him, especially after she had promised emotional transparency. The betrayal, coupled with resurfacing childhood memories and identity confusion, leaves Eddie emotionally broken.

A turning point arrives when Anders Lindberg, the missing twin Eddie never knew he had, enters the narrative. Raised separately, Anders experienced his own set of traumas, including a toxic relationship with Carlo and professional setbacks in the dance world.

He finds meaning through choreography and activism but is haunted by the absence he cannot name: the missing half of himself. His discovery of Eddie leads to a silent but powerful reunion, where they recognize one another as reflections—literal mirror images—of the lives they could have shared.

The reunion marks the beginning of Pär’s decline. The force that once sought to dominate now watches powerlessly as the twins embrace.

Britta, their birth mother, makes a secretive return to New York hoping for reconciliation, but Pär, fearing his extinction, orchestrates her fatal accident through Eddie’s body. This final act of sabotage causes immense guilt, pushing Eddie further into psychiatric care.

Yet it is this same crisis that initiates truth-telling among those around him.

Althea Wynter, Lucy’s sister, pieces together the connections and facilitates the reunion of the twins. As they travel to Sweden to uncover their roots, Eddie and Anders learn that Tyrone Wynter was their biological father—a revelation that reframes their earlier relationships with the Wynter family and explains much of their internal turmoil.

Britta’s abandonment, once seen as cruel, is now understood in the context of societal pressure, racial stigma, and youth. These revelations allow the brothers to begin healing, reconciling with the past without being imprisoned by it.

The novel closes on a hopeful note: Althea’s wedding becomes a symbol of unity and regeneration. Lucy returns, pregnant and seeking reconciliation, supported by Robert.

Eddie and Anders attend the celebration, their bond now solidified. Yet the story does not offer complete closure.

Pär, once dominant and now a shadow, reflects on his fading presence. His final thoughts suggest that while he no longer controls Eddie, his existence, born from trauma and division, remains a part of the whole.

Mirror Me offers a compelling portrait of fractured identity, lost family, and the journey toward integration. It portrays not just the clinical reality of dissociative identity disorder but the emotional weight of being caught between racial identities, familial expectations, and a mind at war with itself.

Eddie’s story—at once tragic and redemptive—is ultimately about the quest to feel real, to belong, and to see oneself clearly through the eyes of others and, finally, one’s own.

Characters

Eddie Asher

Eddie Asher is the fractured heart of Mirror Me, a character whose very identity is the battleground of the novel. A biracial adoptee raised in a white Jewish household, Eddie embodies the complexities of racial, familial, and psychological dissonance.

His life is a collage of splintered memories and dissociative blackouts, shaped by early trauma, racial alienation, and the loss of his biological family. From a young age, Eddie experiences inexplicable lapses in memory, culminating in the emergence of an alternate identity, Pär, who evolves from protector to manipulator.

His adoption by a family that downplayed his racial identity leaves him without a firm cultural foundation, creating internalized confusion that persists into adulthood. His Blackness becomes something he must excavate rather than inherit, an experience that deepens his sense of not belonging anywhere.

Eddie’s navigation through therapy, psychiatric hospitalization, and fractured relationships is marked by a desire for wholeness—yet this quest often threatens to obliterate the parts of himself he doesn’t understand. His relationships—with Lucy, his adoptive brother Robert, his psychiatrist Montgomery, and eventually his twin Anders—reveal a man seeking anchorage in others, only to find mirrors, distortions, and ghosts.

Eddie is a tragic, searching figure, caught in a psychological labyrinth where love and loss are indistinguishable and where self-knowledge comes at a terrible cost.

Pär

Pär is Eddie’s alter, but in Mirror Me, he is much more than a psychological symptom—he is a narrative force, a cunning antagonist, and, paradoxically, a witness to pain. Born from trauma when Eddie was separated from his birth mother Britta, Pär begins as a mechanism of survival but evolves into an autonomous, dangerous entity.

He speaks with elegance and menace, taking pride in his control over Eddie’s mind and body, savoring his role as both guardian and usurper. Pär’s motivations are rooted in self-preservation.

He fears dissolution, which would come with Eddie’s psychological integration or recovery, and so he maneuvers to maintain power—undermining Eddie’s therapy, seducing fellow patients into his narrative, and even orchestrating tragic events, such as Britta’s death. He adopts Britta’s chosen name for Eddie—Pär—as a way of reasserting ownership, turning his identity into an emblem of betrayal.

Yet, for all his menace, Pär is also a deeply wounded character, born from abandonment and raised in the recesses of a child’s subconscious. He is what Eddie could not express: fear, anger, survival instinct.

His very existence blurs the line between identity and invader, between illness and adaptation. Even at the story’s end, his voice lingers like a phantom, refusing to be silenced, a reminder that the psyche’s fractures may never fully heal.

Anders

Anders, Eddie’s twin brother, is the silent thread woven through much of Mirror Me until he steps into the narrative foreground. Raised apart in a more emotionally nurturing environment, Anders channels his longing and pain into dance, eventually becoming a choreographer whose work grapples with identity, desire, and marginalization.

His life, shaped by his own traumas—particularly the devastating fallout of his relationship with Carlo and Lucy—mirrors Eddie’s but with more conscious agency. Unlike Eddie, Anders is able to forge a coherent sense of self, albeit one haunted by the inexplicable sense of a missing part of him.

That part, of course, is Eddie. Anders’s love is wide-ranging and generous, even when it leads to his undoing.

His romantic devastation at the hands of Carlo and Lucy shapes his exit from the Wynter orbit, but it is his return and his quest for truth that catalyze the story’s resolution. When he finally finds Eddie, the reunion is both redemptive and shattering, collapsing the illusion of separateness that had defined their lives.

Anders provides the counterbalance to Eddie’s chaos: a man who has also suffered but who has managed to hold onto his wholeness. Through him, the novel offers a path toward reconciliation—not just with others, but with oneself.

Lucy Wynter

Lucy is the enigmatic gravitational center around which much of Mirror Me orbits. Biracial, Jewish, and emotionally labyrinthine, she shares a mirror-like quality with Eddie that is both tantalizing and destabilizing.

Her relationships—with Eddie, Robert, Carlo, and Anders—are fraught with contradictions: intimacy mingles with betrayal, care with cruelty. To Eddie, she represents a connection both past and present, spiritual and erotic, yet unattainable.

Their bond borders on obsessive, tinged with both psychic recognition and emotional unease. To Anders, Lucy is the epicenter of heartbreak, the one who unleashes a cruel rumor that derails his career and exiles him from the Wynter orbit.

Her actions often seem reactive and destructive, yet they stem from deep reservoirs of grief, confusion, and marginalization. Lucy is a child of a family that both reveres and sidelines her, and her attempts to assert control—over men, over narrative, over love—often collapse into chaos.

Yet, by the novel’s end, Lucy returns, pregnant and humbled, ready to build something new. Her evolution from a volatile presence to a woman seeking stability mirrors the broader theme of the novel: the messy, painful, and necessary path to self-reckoning.

Robert Asher

Robert is both a literal and symbolic figure in Eddie’s life—a golden child turned false prophet. Charismatic, charming, and emotionally elusive, Robert is Eddie’s adoptive older brother and one of the most influential figures in shaping his psychological development.

On the surface, Robert offers protection and admiration, particularly during Eddie’s childhood. But the novel suggests a darker undercurrent: a history of manipulation, perhaps even abuse, that Eddie cannot fully recall or comprehend.

Robert’s presence haunts Eddie’s memories, often appearing at the edges of traumatic events, such as the bathtub incident and the gaps in Eddie’s psychiatric history. He is also romantically entangled with Lucy, creating a triangulation that fuels Eddie’s confusion and jealousy.

In adulthood, Robert remains opaque, unwilling to acknowledge Eddie’s psychological suffering, and possibly complicit in enabling it. His confrontation with Eddie about Lucy’s disappearance underscores the emotional distance that has always existed between them.

Robert is a symbol of a family that cannot fully see Eddie for who he is—an emblem of repression masquerading as love.

Dr. Montgomery

Dr. Montgomery is Eddie’s psychiatrist at Hudson Valley Psychiatric Hospital and serves as both a potential ally and a subtle antagonist.

As the author of The Splintered Self, Montgomery initially offers Eddie hope for understanding his condition. But his fascination with Pär—especially as Pär begins to speak independently—morphs into something voyeuristic.

Montgomery becomes less a healer and more a spectator, captivated by the intellectual puzzle that Eddie’s mind presents. His detachment, though cloaked in clinical professionalism, becomes another form of betrayal.

He fails to recognize the emotional danger Pär poses, instead becoming enthralled by Pär’s charm and clarity. This dynamic mirrors the broader pattern in Eddie’s life: authority figures who are intrigued by his pain but fail to protect him from it.

Montgomery ultimately reinforces the novel’s central question—who gets to define sanity, and at what cost?

Britta

Britta, the biological mother of Eddie and Anders, haunts the novel as both absence and remorse. A Swedish teenager when she gave birth, Britta’s decision to give up one son while keeping the other fractures the twins’ lives before they even begin.

Her later life is shaped by regret and longing, leading her to secretly track Eddie. But before she can reunite with him, Pär intervenes, luring her into what becomes a fatal accident.

Britta’s death is both a literal and symbolic erasure: the mother who might have offered answers, closure, and healing is silenced by the very force her abandonment helped create. She is a tragic figure, one whose mistakes are rooted not in cruelty but in youth, shame, and a lack of support.

Her story is a testament to how personal histories of trauma can ripple across generations, distorting lives long after the original wound.

Tyrone Wynter

Tyrone is a quietly pivotal character whose influence spans both twins’ lives without their knowing it—he is their biological father. As a mentor to Anders and a patient tended to by Eddie, Tyrone provides a rare space of emotional authenticity and connection.

His poetry, reflections, and dying confessions add depth to the novel’s exploration of identity, particularly Black masculinity. He is a man shaped by secrets, by children he never met or raised, and by a life lived in fragmented emotional truths.

Tyrone’s death is marked by dignity and sorrow, but his legacy endures in the realization of his paternity. That revelation adds a bittersweet texture to the twins’ reunion: the man they both connected with in different ways turns out to be their origin, anchoring their stories in a shared, if unknowable, past.

Tyrone embodies the idea that family can be both accidental and essential, broken and redemptive.

Themes

Identity as Fractured and Conditional

The core of Mirror Me is Eddie’s harrowing navigation through a fractured identity, complicated by dissociative identity disorder, biracial heritage, adoption, and buried trauma. Eddie does not possess a stable sense of self; instead, his identity is segmented, interrupted, and continually revised by both internal and external forces.

The emergence of Pär as an alter is not simply a psychological phenomenon, but a symbolic assertion of how Eddie’s identity has always been dictated by the needs, interpretations, and traumas of others. His name, his race, his familial place, and even his body are all contested terrains.

As Eddie’s therapy progresses, it becomes apparent that his sense of identity was never a coherent whole but a mosaic formed in response to being marginalized, displaced, and misunderstood. He isn’t merely suffering from mental illness—he’s embodying the fragmented experience of someone whose very existence was fractured from birth.

That fragmentation is further compounded by societal denial of his Black identity, familial neglect, and the haunting role of Pär, who begins as protector but evolves into a competitor. The act of integrating these selves is less about elimination and more about recognition, yet even in the final scenes, Pär’s lingering presence suggests that true wholeness is elusive.

Identity, in this novel, is conditional and constructed not just from within but imposed by history, family, culture, and the persistent ache of things forgotten.

Trauma and Memory

Memory in Mirror Me is not reliable—it’s unstable, shifting, and often deceptive, shaped by psychological necessity rather than objective truth. Eddie’s dissociative episodes are marked by temporal gaps and distortions that serve both as protective mechanisms and sites of horror.

His inability to remember key events—his near-drowning, his relationships with Lucy and Robert, and even acts that may involve death—places him in a permanent state of uncertainty. Memory is not just what he has forgotten, but what he has misremembered, reshaped, or suppressed.

Dr. Montgomery’s probing makes this clear: what Eddie believes about his past is not only partial but also potentially false.

Pär’s memories offer alternate accounts, ones that conflict with and destabilize Eddie’s fragile narrative. Even artistic representations, like Ray Gilooley’s drawing of Lucy on the train tracks, carry the weight of memory but through a symbolic, threatening lens.

These moments ask the reader to question the reliability of any recollection, particularly when trauma is involved. The trauma Eddie suffered—abandonment by his birth mother, racial alienation, the mystery surrounding Robert, and the ambiguous loss of Lucy—is deeply embedded in his psyche, manifesting not as events he can recount but as echoes in his body and mind.

His identity becomes a battleground between remembering and forgetting, between truths that must be unearthed and those that may be too dangerous to fully confront. In this world, memory is not a foundation—it is a minefield.

Racial Alienation and Cultural Displacement

Race operates in Mirror Me not as a background trait but as a destabilizing force that subtly shapes every aspect of Eddie’s life. Raised by a white Jewish family that minimized race, Eddie grows up without cultural context or language to make sense of his Blackness.

This absence is not neutral; it leaves him unmoored, invisible in some settings and hyper-visible in others. When he finally begins to explore Black culture during college, the shift is not seamless—it is fraught with self-doubt, social awkwardness, and the residue of internalized erasure.

His interactions with Stephen and CeCe are enlightening, but they also highlight how much of his formative experience was shaped in isolation from the culture that could have grounded him. Eddie’s biracial identity becomes yet another layer of dissonance: neither fully embraced nor fully belonging anywhere.

The revelation that his birth father is Tyrone Wynter—a celebrated Black artist—adds cruel irony to this theme. Eddie spent time with Tyrone under a false identity, never recognized or claimed, and this dynamic reinforces how identity is often obscured by racial assumptions and secrets.

Pär’s emergence, too, reflects a survival response not just to maternal loss but to racial displacement; he is a figure born of abandonment by both mother and culture. Ultimately, Eddie’s racial identity is less about heritage and more about estrangement, where every interaction is shaped by what has been denied, distorted, or kept hidden.

The Fragility of Familial Bonds

Family in Mirror Me is a source of longing, betrayal, and elusive truths. Eddie’s adoption, while well-intentioned, disconnects him from his origins and places him in a family that does not fully acknowledge his psychological or racial needs.

His relationship with Robert, initially perceived as nurturing, unravels under the weight of traumatic recollections and suspicion. As childhood memories resurface, it becomes evident that Robert may have played a more sinister role in Eddie’s formative years than previously believed.

This possibility contaminates every memory of affection or protection, leaving Eddie unsure whether love or harm has governed his relationships. The Wynter family, too, offers a mirror of familial dysfunction and complicated love.

Eddie’s bond with Tyrone is tender but incomplete, constantly filtered through the missing figure of Andy. Lucy, tangled in grief, romance, and identity confusion, is both sister-like and romantically fraught, reflecting Eddie’s yearning for belonging in every interaction.

Even Britta, the biological mother, is a tragic symbol of broken family ties. Her return is not a healing reunion but a fatal encounter orchestrated by Pär, who sees her as a threat.

Familial love in the novel is conditional, often withheld or sabotaged, and rarely redemptive. Only through Anders does Eddie find a semblance of familial unity, but it arrives too late to restore what was lost.

These fragile bonds are marked by absence, secrets, and the shattering impact of betrayal.

The Self as Haunted and Divided

Throughout Mirror Me, Eddie is pursued not only by his past but by the other versions of himself that populate his mind and influence his actions. Pär is the most dominant, but not the only spectral presence—Mirror Eddie, The Other, and eventually even the voice of Anders echo through Eddie’s internal world.

These selves are not merely psychiatric phenomena; they represent the psychological residue of a life fractured by unmet needs, failed relationships, and repressed truths. The haunting in this novel is not supernatural but existential.

Eddie is haunted by who he might have been, by memories he cannot trust, by a mother he never knew, and by a brother he was separated from at birth. The novel suggests that the self is not a singular entity but a chorus of voices, some nurtured, some silenced, and some dangerous.

This fragmentation becomes physical at times, with Pär taking control of Eddie’s body, speaking aloud, influencing others, and even committing acts that Eddie cannot remember. The divide is not only between self and other, but within the self, with no clear boundary of accountability or agency.

The eventual integration with Anders offers hope, but not closure. Pär’s final whisper reminds the reader that the self can never be fully unified, only momentarily aligned.

Eddie’s journey suggests that to be human is to be haunted—not just by what has been done to us, but by the selves we might still become.