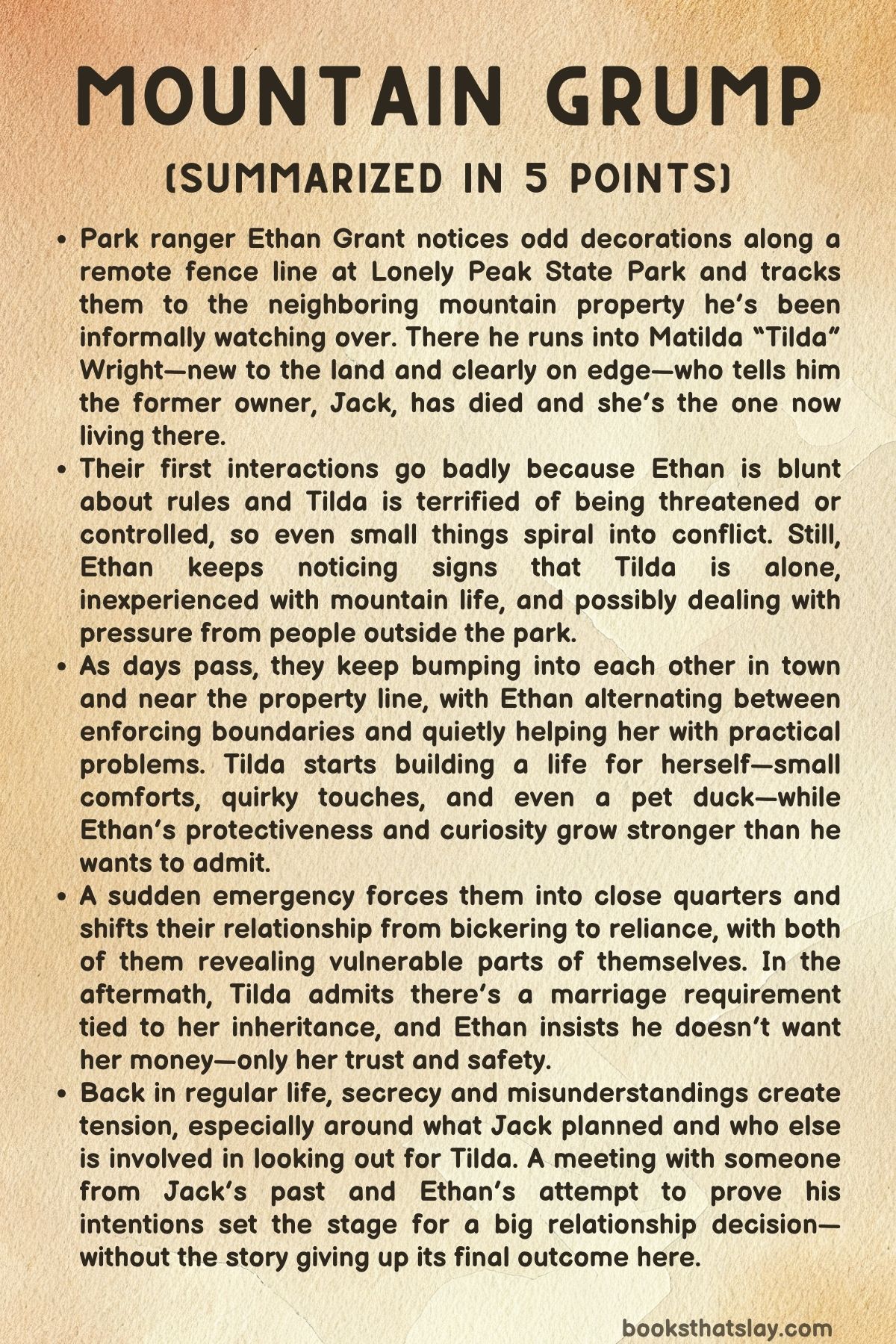

Mountain Grump Summary, Characters and Themes

Mountain Grump by SJ Tilly is a contemporary romance set against the quiet isolation of a rugged mountain town. Ethan Grant is a blunt, rules-first park ranger who likes his solitude and keeps his feelings locked down.

Matilda “Tilda” Wright is the opposite: colorful, gentle, and determined to build a new life in the wilderness after inheriting a remote property. When Ethan discovers her on land he’s been keeping an eye on, their first meeting is a disaster—misunderstandings, bad timing, and bruised pride. What follows is a slow shift from irritation to trust, and then to something neither of them planned. It’s the 3rd book in the Mountain Men series.

Summary

Ethan Grant is patrolling Lonely Peak State Park when he hears an oddly cheerful humming near a remote border fence. The area is quiet, and the neighboring private property belongs to Jack, an older man Ethan has checked on for years.

Jack normally shows up for the summer, but he hasn’t returned, which has been bothering Ethan. When Ethan reaches the fence line, he finds purple ribbon tied in bows along the barbed wire and threaded into the nearby trees.

Because the fence is on park land, Ethan treats it as vandalism. He starts pulling it down, growing more annoyed as it snags on the barbs and forces him to cut it away.

Determined to figure out who did it, Ethan slips onto Jack’s land and follows the long gravel drive. He sees signs of recent activity: fresh tire tracks, open doors, moving boxes, and Jack’s truck in the garage.

Then he spots a stranger—a woman with lilac hair in a short pink dress—humming while hanging crystal suncatchers from tree branches like she’s decorating for a celebration. Ethan calls out sharply.

Startled, the woman panics, throws what she’s holding, and falls hard on the gravel, scraping her hands and knees.

The woman, Tilda Wright, is terrified. Ethan’s size, uniform, tattoos, and gun make her assume the worst.

She begs him not to shoot, then grabs craft scissors as a desperate weapon. Ethan, confused by her fear, asks where Jack is.

Tilda blurts out that Jack is dead and that it happened two weeks earlier. Ethan is stunned and demands more answers.

When he asks about Jack’s heir—someone Jack called “Matty”—Tilda admits she is Matty: Matilda is her full name, and Jack was the only person who called her that.

Ethan realizes he assumed Matty was a man, and the encounter turns tense and awkward. He criticizes Tilda’s ribbon and decorations, calling her “ridiculous” and ordering her to remove anything attached to park property.

Tilda flinches at the insult, forces a smile, and agrees while quietly crying. She retreats into the house and locks the door.

Ethan, unsettled by how frightened she seemed and by the mention of someone possibly “sending” him, leaves her supplies where she dropped them and returns to the park side of the fence, trying to convince himself he handled it correctly.

Alone in the house, Tilda tries to settle into a place that feels both magical and intimidating. She remembers how Jack arranged everything for her: a letter explaining he was terminally ill and planned a legal, assisted death; a key; travel plans; and money to help her start over.

Tilda is sore, hungry, and overwhelmed, but she’s drawn to the quiet beauty of the mountain view and wants to make the space feel like hers. With no internet and limited comforts, she finds Jack’s neatly organized DVD collection and uses the sound of movies to cut the silence.

The next day, Tilda decides to brighten the house and yard with wildflowers. She plays music out loud, partly to calm herself and partly to warn animals she’s nearby.

When she goes back to the fence, she discovers all her ribbon has been removed. She spots purple flowers on the state park side and, ignoring warning signs, squeezes through the sagging barbed wire in a clumsy, scratchy mess.

Ethan sees her doing it and stops her, which triggers another loud scream and another flare of irritation on both sides.

Ethan tells her cutting flowers in the park is illegal and starts writing a ticket. Tilda, stubborn and embarrassed, proves she can be just as hardheaded as he is.

Their argument escalates until Tilda blurts out an absurd insult that catches Ethan off guard. For the first time, he laughs—big, unrestrained laughter that breaks the tension.

He crumples the ticket and tells her to leave before he changes his mind. Without making a big show of it, he helps her back through the fence so she doesn’t snag her dress again, then reminds her to take care of her scraped knees.

Back home, Tilda tries to focus on building a life. She names a mounted deer “Deerdra,” becomes delighted by a duck that keeps visiting, and eventually calls it Quackers.

She drives Jack’s old truck into town, where she’s surprised that people are simply… normal with her. Still, everyday tasks feel like tests she’s afraid to fail.

At the hardware store, she buys a bright kiddie pool to make a duck-friendly “pond,” only to struggle with it in the wind. Ethan shows up, helps her load it, straps it down properly, and apologizes for calling her ridiculous.

His small gentleness—like adjusting his hat onto her head so her hair fits—lands harder than any grand speech.

Ethan’s protective streak becomes obvious when a friendly local man approaches Tilda. Ethan steps in, blocks the interaction, and sends the guy away, even though he can’t fully explain his own behavior.

He keeps circling back into Tilda’s orbit, half irritated, half compelled. Tilda, for her part, keeps trying to make sense of the gruff ranger who acts like she’s a problem and then quietly solves the problems around her.

As their connection grows, circumstances push them into relying on each other in a much more serious way when they end up stranded after a plane crash in the mountains. Survival strips away their usual defenses: Ethan’s need for control and distance, and Tilda’s tendency to hide her fear behind sweetness.

They find a rhythm—food, shelter, keeping warm, keeping watch—and the forced closeness turns into real trust and physical intimacy.

During their time stuck together, Tilda reveals the condition tied to Jack’s inheritance: she will receive two million dollars, paid out over several years, but only if she’s married before her thirtieth birthday. Their marriage—done quickly under extreme circumstances—suddenly has more weight.

Tilda worries Ethan will think she trapped him for money. Ethan refuses any claim to her inheritance and insists he wants her, not her bank account.

Still, he keeps one secret: Jack asked him to look after her, and Ethan fears that if she knows, she’ll believe every kind act was part of an assignment.

After they’re rescued, the return to normal life is jarring. Tilda goes home to an empty, silent house and realizes how much Ethan changed the feeling of it just by being there.

Ethan, alone with his guilt, rereads Jack’s letter instructing him to keep Tilda safe and follow her lead, then throws it away, choosing to see his marriage as real even if it started in chaos.

On Tilda’s birthday, she learns the first portion of her inheritance has already been deposited, confirming the will’s timeline. Ethan shows up with a gift and an awkward, sincere attempt at celebration—made more chaotic when Quackers attacks him and Ethan, unbelievably, catches the duck midair.

Tilda laughs, warmed by the fact that he came, and by how natural it feels to have him in her space.

When Tilda later discovers purple ribbon tied along the fence again—matching the ribbon Ethan once bought—an older man named Stephen calls and asks to meet. Ethan ends up flying her himself.

Stephen turns out to be Jack’s partner, not a frail stranger, and his “weak voice” was partly a setup to nudge Tilda into seeing Ethan again. Stephen helps Tilda understand that Jack’s strange plan was rooted in regret, love, and a desire to protect her future.

The meeting softens Tilda’s anger, and her silence with Ethan begins to lift.

Ethan starts leaving small, practical gifts and messages, steady proof that he’s still there. Eventually, he invites Tilda to an address near the park.

She arrives to find a new public space: Uncle Jack’s Wilderness Camp, built with care and purpose. Ethan explains he donated land to the park so it could become official state property, then used funds Jack left to create something lasting for the community.

He shows his finances to prove he didn’t do it for profit, then proposes again with a star-themed ring, finally explaining that “Starlight” means she’s his guiding point—his way home. Tilda accepts, claiming him as her husband not out of obligation, but out of choice.

In the epilogues, they host a winter celebration at the camp that brings the town together, honoring Jack’s memory and what they’ve built. On their first anniversary, they return to their cabin, more playful and secure.

Tilda reveals she’s ready to start a family, and Ethan meets that future with the same steady devotion he’s been learning to show all along.

Characters

Ethan Grant

Ethan is introduced as a man who has built his identity around structure, boundaries, and responsibility, and his work as a park ranger is more than a job—it’s the language he uses to feel in control of a world that has already taken too much from him. His first instinct when confronted with Tilda’s ribbon and crystals is not curiosity but enforcement; he reads beauty as disorder and decoration as violation because he experiences the park as something he must protect through rules.

That rigidity, however, isn’t simple arrogance—it’s grief-shaped discipline. Jack’s absence hits Ethan harder than he expects because Jack occupied a rare emotional category for him: a steady presence and a quiet friendship that didn’t demand vulnerability.

When Tilda appears, Ethan’s reaction is thorny and contradictory: attraction triggers shame, shame turns into anger, and anger becomes harshness, especially when he calls her “ridiculous.” Yet the story consistently reveals that Ethan’s grumpiness is a cover for an intense protective drive. He watches, intervenes, teaches, and provides—ratchet straps, warnings, guidance, even small acts like lifting barbed wire with his boot—while trying to pretend he is only doing his duty.

The plane-crash survival section exposes his truest self: competent, calm under threat, and emotionally earnest when danger makes pretense impossible. His love is physical, yes, but it’s also deeply caretaking—he feeds her, cleans, guards, carries her, tends her feet, and anchors her fear with steadiness.

His central moral conflict is secrecy: he withholds Jack’s request to look after Tilda, not to manipulate her for money, but because he is terrified of being seen as yet another person controlling her life. That fear nearly costs him everything, and when he finally chooses transparency—showing his finances, showing the camp, proposing again—he becomes the version of himself that love has been pushing him toward: not just the enforcer of boundaries, but a man capable of building a home inside them.

Matilda “Tilda / Matty” Wright

Matilda arrives in the mountains as someone trying to start over with a mix of fragility and fierce determination, and her bright aesthetic—lilac hair, pink dress, ribbon bows, crystal suncatchers—is not superficial decoration but a survival tactic. She transforms space to make it feel safe, legible, and hers, especially after receiving life-altering news about Jack’s death and inheritance.

Her humming is a perfect encapsulation of who she is: a gentle habit that is also practical, a way to announce her presence to animals and, symbolically, to the world that often overlooks or intimidates her. Tilda’s fear when Ethan appears—begging him not to shoot, assuming he was “sent” by someone—reveals a history of being controlled, threatened, or treated as powerless, and the way she grabs craft scissors like a weapon shows her instinct to protect herself even when she’s shaking.

What makes her compelling is how quickly softness flips into backbone; she cries when Ethan insults her, but she still chooses action—moving alone, learning to drive the old truck, going to town, figuring out bags at checkout, taking herself to a laundromat and then a gym, attempting independence in small, brave increments. Her humor is another form of courage: the absurd “butthole” insult that cracks Ethan open isn’t just comedic, it’s her refusing to be cowed by his authority.

Over time, her “sparkle” becomes less a shield and more an authentic expression of joy—Quackers, flowers, Deerdra, the kiddie pool, the DVDs—signs that she has a capacity for wonder even in loneliness. The inheritance condition forces her into a marriage that could be read as transactional, but her internal posture is consistently emotional rather than greedy; she is embarrassed by the requirement, offers to share, and is desperate to be believed.

Her deepest need isn’t money or rescue—it’s autonomy paired with safety. The relationship works when Ethan stops positioning himself as her guard and starts treating her like a partner with equal say, and by the end, her acceptance of him isn’t surrender; it’s a chosen homecoming.

Her final shift—initiating family plans and stepping into a future she wants—shows her arc completing: from a woman bracing for what her family will do to her life, to a woman actively authoring it.

Jack

Jack functions as the story’s absent gravitational center: even after death, he shapes the plot, the romance, and the emotional stakes through what he leaves behind. To Ethan, Jack is the closest thing to a friend, a quiet anchor who exists outside Ethan’s usual guarded relationships; Ethan’s grief is so heavy precisely because he didn’t realize how much he relied on Jack until Jack was gone.

To Matilda, Jack is both refuge and complication—he offers her escape, money, and a hidden home, but he also constructs a system that steers her choices, including the marriage condition that collapses her future into a deadline. What makes Jack interesting is that his care is real but imperfectly expressed: he provides practical lifelines (key, check, arrangements, stocked pantry, small comforts), yet he keeps secrets that ripple outward, leaving Matilda to process revelations after the fact.

His legacy is double-edged—he gives Matilda the chance to reinvent herself, but he also forces her to confront what it means to be “helped” without being asked. In the end, Jack’s most important function is as a bridge: he believes Ethan is good, he believes Matilda deserves safety and love, and his strange, controlling plan is his flawed attempt to push two guarded people toward a life neither would have risked alone.

Sandra

Sandra is a sharp counterbalance to Ethan’s severity, serving as both comic relief and emotional translator. She reads Ethan quickly, teases him, and refuses to accept his gruffness at face value, which forces him into tiny moments of honesty he might otherwise avoid.

Her presence also signals that Ethan isn’t isolated by circumstance—he has family—but he is emotionally isolated by habit, and Sandra is one of the few people who can tug at that armor without triggering outright retreat. She helps in practical ways, like directing him to where he can buy ribbon, but her more significant role is relational: she represents community, normalcy, and the possibility that Ethan can be known and still accepted.

By appearing later in shared celebrations and milestones, she reinforces the story’s movement from secrecy and solitude toward public belonging, showing that Ethan and Matilda’s relationship isn’t just private passion—it becomes part of a wider, warmer social world.

Fisher

Fisher enters as a seemingly harmless friendly man, but his real narrative purpose is to expose Ethan’s possessiveness and emotional investment before Ethan is ready to admit it. Ethan’s immediate physical positioning—blocking Fisher, dismissing him—makes visible what Ethan tries to deny internally: he feels territorial not about land, but about Matilda’s safety and attention.

Fisher’s friendliness also highlights Matilda’s social vulnerability; she is new, alone, and learning to navigate attention, and Fisher’s presence tests whether Ethan’s protectiveness is respectful partnership or controlling behavior. As the story progresses into community moments where Fisher is included rather than treated as a threat, his role shifts from catalyst to confirmation: Ethan’s love matures from reactive guarding to confident commitment, and Fisher becomes part of the town fabric that surrounds the couple rather than a rival outside it.

Clark

Clark appears briefly but pointedly as a symbol of predatory possibility and Matilda’s exposure. His act of following her out of the gym lands as a reminder that Matilda’s independence comes with risks she hasn’t fully learned to manage yet, and it also intensifies Ethan’s internal tension: he wants to protect her, but he fears that stepping in will make him look like another controlling man in her life.

Clark’s narrative weight is less about who he is as a person and more about what he represents—how quickly everyday spaces can become unsafe for someone alone, and how Ethan’s vigilance is sometimes grounded in real threat rather than mere jealousy.

Richard

Richard, Jack’s lawyer, is a calmer, kinder version of the “people who are supposed to handle things,” and he matters because he treats Matilda like a person rather than a problem to be managed. When Matilda calls overwhelmed by the deposit, Richard provides clarity and reassurance—taxes covered, payout schedule explained—without judgment, and he also delivers something she quietly craves: evidence that Jack’s care wasn’t entirely solitary or secretive.

By telling her that he and another friend promised Jack they’d look after her, Richard expands Matilda’s world from isolation to a network of adults who, at minimum, intend her well. He is part of the story’s slow correction of Matilda’s expectation that support always comes with cruelty, strings, or humiliation.

Stephen

Stephen is the story’s late-stage truth-teller, but he’s also a mirror held up to Jack’s contradictions. His reveal—healthy, lively, and connected to Jack as a partner—reframes Jack’s secrecy as something rooted in fear, shame, and protectiveness rather than simple omission.

Stephen’s deliberate trick with the “frail voice” is ethically messy, and that messiness is the point: it echoes Jack’s controlling inheritance condition in miniature, reinforcing that these older men sometimes choose manipulation because they believe it will produce safety and love. Yet Stephen’s impact on Matilda is largely healing because he gives her context, laughter, and a sense that Jack’s life contained joy she never got to witness.

He also removes some of Ethan’s stain by shifting responsibility back where it belongs—onto Jack’s plan—allowing Matilda to reconsider Ethan as a man who made mistakes, not a man who used her. Stephen therefore acts like a hinge in the reconciliation: he doesn’t fix everything, but he loosens the emotional rust so the door can open again.

Quackers

Quackers is more than a cute pet; the duck is a symbol of the home Matilda is building and the softness she insists on keeping even when life turns harsh. Matilda’s bond with Quackers reveals her nurturing instincts and her need for companionship that doesn’t judge, demand, or intimidate.

The duck also becomes a comedic stress test for Ethan’s toughness—when Quackers attacks him and Ethan catches the bird midair, the moment blends humor with tenderness, showing Ethan can enter Matilda’s whimsical world without breaking it. In a story where control and protection are constant themes, Quackers represents something beautifully uncontrolled: affection that’s loud, inconvenient, and sincere, the kind of life-noise that turns a lonely mountain house into a lived-in home.

Deerdra

Deerdra, the mounted deer head Matilda names, is a small but telling character surrogate: an object turned into a “presence” so the house feels less empty. By talking to Deerdra, Matilda externalizes loneliness in a way that remains playful rather than despairing, which underscores her coping style—she transforms discomfort into something she can narrate, decorate, and therefore survive.

Deerdra also highlights the contrast between the cabin’s masculine, rustic inheritance and Matilda’s determination to soften it, making the home reflect her inner life rather than just Jack’s past.

Themes

Healing from Grief and Loneliness

The emotional center of Mountain Grump lies in how both Ethan and Matilda learn to navigate loss and isolation. Ethan’s world is built around silence, rules, and self-imposed solitude.

His duties as a park ranger and his reluctance to form attachments stem from years of emotional withdrawal, perhaps due to the deaths of his parents and his inability to trust human connection. In contrast, Matilda’s loneliness takes a different shape—hers is not chosen but enforced by neglect and control from her family.

When she arrives at her late uncle’s property, she carries grief for a man who finally saw her worth, and also the heavy emptiness of a life spent without unconditional care. Their meeting begins in misunderstanding and fear, yet through proximity and mutual vulnerability, both begin to heal.

The wilderness around them becomes symbolic of their emotional terrain—untamed, beautiful, and occasionally dangerous. Grief becomes less of a wound and more of a landscape they learn to walk together.

Ethan’s rigid emotional walls soften as he realizes that compassion and connection do not threaten his strength, while Matilda finds in him the steady presence that allows her to grow secure. By the end, grief is no longer just an absence but a memory integrated into new beginnings—Jack’s death leads them to each other, and in that sense, love becomes both a remedy and a continuation of what was lost.

Fear, Control, and the Search for Safety

Fear governs much of Matilda’s early existence, shaping her every response to the world. Her instinctive panic when Ethan first appears—pleading not to be shot and brandishing scissors in self-defense—reveals a lifetime of trauma and coercion.

That fear is both physical and psychological, rooted in her history with manipulative family members and the feeling that she must always be ready to protect herself. Ethan, meanwhile, represents the illusion of control.

His job requires authority and caution; his demeanor is built on discipline and boundaries. Yet his anger, especially at being “tricked” by Jack or confronted with feelings he cannot rationalize, shows that control is his coping mechanism rather than a true strength.

The novel juxtaposes their approaches to safety: Matilda’s self-protective chaos against Ethan’s structured repression. When they are stranded together after the plane crash, those defenses are stripped away.

Safety no longer means avoidance but trust—trust that Ethan will protect her not because he is obligated, but because he cares, and trust that Matilda can stand her ground without fleeing. The transformation of fear into security is not sudden; it occurs through gestures of care—Ethan washing her clothes, Matilda offering honesty about her inheritance, and both allowing vulnerability to replace suspicion.

The narrative ultimately argues that true safety does not come from isolation or power but from the courage to be seen fully by another person.

Love as Redemption and Growth

Romance in Mountain Grump is not merely attraction but a process of redemption. Ethan’s relationship with Matilda dismantles his cynicism and guilt, especially his unspoken shame over failing to protect others in his past.

Matilda’s love gives him a reason to reconnect with life’s gentleness—something he has long buried beneath duty. For Matilda, love is an awakening; it teaches her that affection can exist without judgment or control.

She enters the story as someone desperate to prove herself, constantly apologizing and shrinking to avoid conflict. Her dynamic with Ethan, though volatile at first, evolves into mutual transformation.

Their physical intimacy after the mountain lion incident is not portrayed as conquest but as release—a moment when survival, fear, and emotion fuse into tenderness. Later, the revelation of Jack’s letter tests their bond, forcing them to choose between resentment and understanding.

Ethan’s decision to confess and rebuild trust marks his moral rebirth, while Matilda’s forgiveness signals her growth beyond her trauma. The final proposal, set against the newly built wilderness camp, symbolizes how their love has matured from survival into purpose.

Through love, both find not perfection but wholeness—a shared redemption that honors Jack’s memory and their own hard-won peace.

The Intersection of Nature and Human Emotion

Nature in Mountain Grump is more than setting; it mirrors the internal lives of its characters. Lonely Peak’s forests, the mountains, and the unpredictable weather embody both serenity and danger—the same balance present in Ethan and Matilda’s relationship.

The wilderness strips away pretenses: isolation forces honesty, and survival demands collaboration. For Ethan, the park represents order and stability, a domain he can manage through rules and vigilance.

For Matilda, it begins as an alien, frightening world but becomes a source of healing and belonging. Her ribbons, crystals, and decorations—once dismissed as “ridiculous”—become expressions of joy and individuality reclaiming space in a harsh environment.

The natural world reflects the shifting dynamic between them: storms align with conflict, stillness with reconciliation. When Ethan later builds “Uncle Jack’s Wilderness Camp,” the environment becomes the manifestation of balance—human care enhancing natural beauty rather than exploiting it.

Nature ultimately stands as a metaphor for emotional truth: untamed yet nurturing, capable of both destruction and renewal. The landscape’s rawness teaches both characters humility, patience, and the necessity of coexistence—lessons that anchor their love and their personal evolution.

Inheritance, Legacy, and the Meaning of Home

The theme of inheritance in Mountain Grump extends far beyond money or property; it represents emotional continuity and the search for belonging. Jack’s death initiates every major event, his will acting as both catalyst and test.

His unconventional condition—that Matilda must marry before turning thirty—appears transactional but is, in essence, an act of faith. He entrusts her future to someone capable of giving her what family failed to provide: love, protection, and freedom.

Ethan’s connection to Jack adds another layer—he inherits not wealth but responsibility and affection, stepping into a role that challenges his solitary nature. Through Jack’s posthumous guidance, both characters inherit the chance to rebuild themselves.

The mountain cabin, initially a symbol of isolation, transforms into a home—a place where memory, love, and purpose converge. By the end, when Ethan converts his inheritance into a public wilderness camp, the concept of legacy reaches fulfillment.

He and Matilda create something enduring, an emotional and physical space that honors Jack’s generosity and their shared journey. Home is no longer tied to walls or geography but to mutual respect, shared purpose, and the courage to start anew.

This transformation of inheritance into community becomes the novel’s affirmation that love and memory, when accepted and shared, create the truest form of belonging.