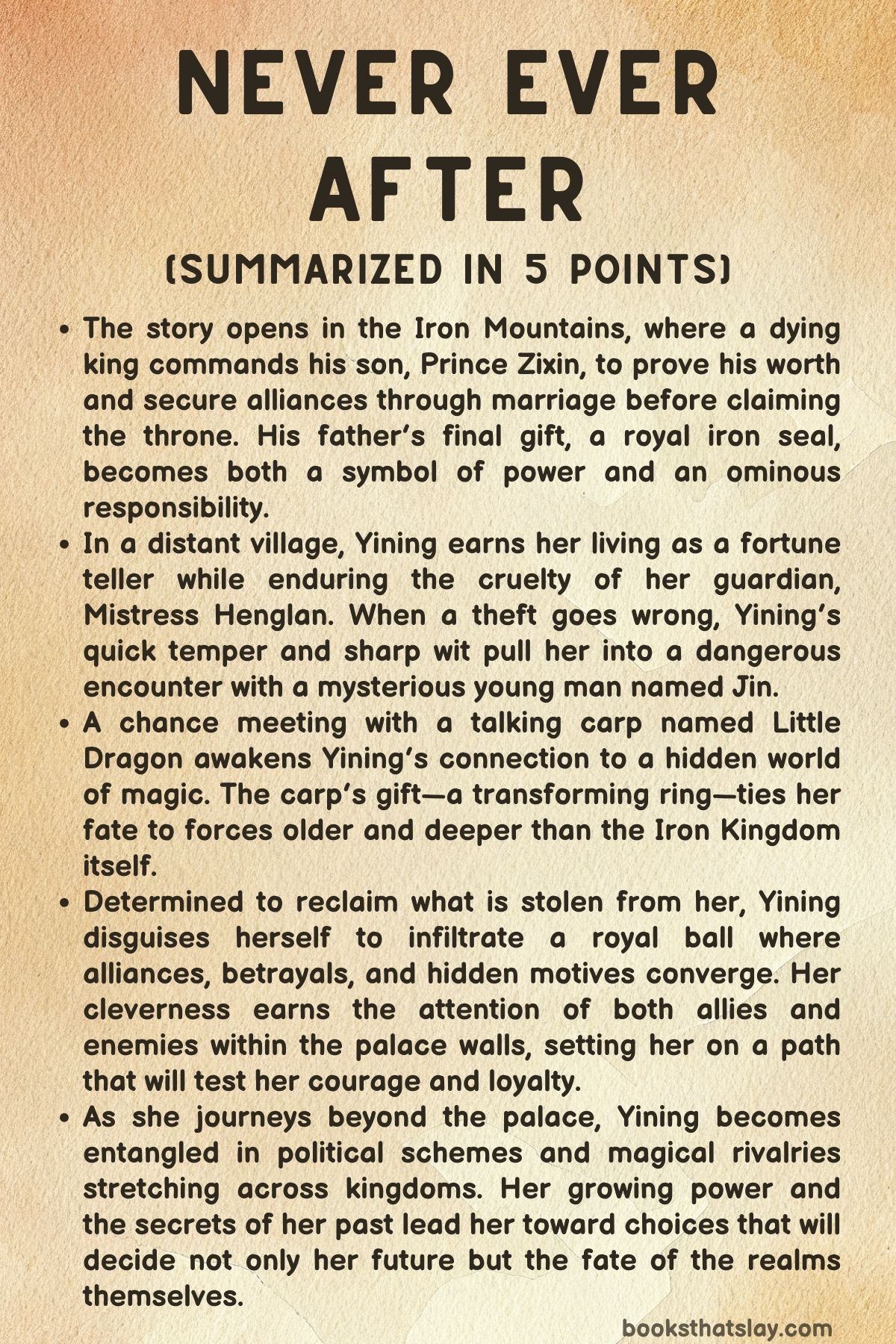

Never Ever After Summary, Characters and Themes

Never Ever After by Sue Lynn Tan is a fantasy romance set across rival realms where iron-fueled power clashes with old, secret magic. It follows Yining, a young woman scraping by as a fake fortune teller under a cruel guardian, until a strange inheritance—sealed into a ring—pulls her toward the royal court.

What begins as a fight to survive and recover what was stolen becomes a larger reckoning with identity, family, and the price of power. With court intrigue, shifting loyalties, and dangerous bargains, Yining is forced to decide who she can trust and what she is willing to become.

Summary

The king of the Iron Mountains, master of the richest mines and the strongest of the Three Kingdoms, lies dying and summons his son. He orders the prince to choose a bride to secure the throne and strengthen alliances, and he speaks openly of future conquest against Thorn Valley and Mist Island—lands tied to magic that the Iron Mountains fear and resent.

Before he dies, the king gives the prince the royal iron seal, carved with a chrysanthemum and set with a rare jewel, and warns him to keep it close. He also sets tasks the prince must complete before he can claim the crown.

Far from the palace, in Twin Cypress Village, Yining lives under the control of her step-aunt and guardian, Mistress Henglan. On market days Yining poses as a fortune teller, offering gentle “readings” while Henglan steals from customers.

Yining is terrified of being sent to the mines, where her uncle died after being condemned there, and she clings to a plain wooden ring she refuses to remove. During one market day, a confident young man confronts her about her act.

He calls himself Jin, pays her inflated price without complaint, and asks whether he will find what he is seeking in the mountains. Yining gives him misleading directions out of spite, but he remains calm and amused.

Their paths cross again when soldiers arrive to arrest Yining for stealing an iron necklace—something Henglan actually took. Henglan slips away, leaving Yining to face punishment that would likely mean the mines.

Yining fights her way free and flees through the crowded market. In a dark building, someone grabs her; she lashes out with a blade and realizes she has cut Jin.

He insists he means no harm and warns that the gates are sealed and searches are underway. Cornered, Yining bargains: she will owe him a favor he can claim later if he helps her escape.

Jin agrees, makes her swear, and hides her under his cloak, suggesting the guards will not dare search his carriage.

Inside the carriage, Yining treats his wound. Jin claims he is an advisor traveling under a powerful crest, and at the checkpoint the soldiers quickly back down, bowing as the carriage passes.

Jin lets her out near a forest, reminding her he will collect his debt when he chooses.

Yining heads to an overgrown pond near family graves and finds something impossible: pear trees heavy with ripe fruit out of season and glowing flowers ringing the water. Hungry and shaken, she eats and rests.

When she tries to catch a fish, a carp rises and speaks. It warns her not to harm it and hints it has been sent by her mother.

Yining returns later, and the carp—blunt, bossy, and oddly protective—pushes her to cut ties with those who hurt her. She names it Little Dragon.

The carp reveals the wooden ring is part of Yining’s inheritance and uses borrowed magic to form a luminous thorned flower-circlet meant to bind with the ring. The bargain is brutal: once Yining accepts the power, she will be bound to it for life—if the ring is taken, she will die.

Still, Yining chooses the ring, and it transforms into a smooth, radiant stone-like band. That night, she dreams of a girl dragged through bright warmth, a vision that feels like a memory.

Before Little Dragon’s magic fades, it gives Yining a final gift: a bundle with a pale blue embroidered silk dress, a coral-butterfly hairpin, and fine brocade shoes. Soon after, Yining is attacked in the woods and knocked unconscious.

She wakes locked in the storeroom where Henglan has punished her before. The ring is gone, and a red flower-shaped mark burns beneath her finger.

Henglan taunts her with proof of what she has done: she has cooked Little Dragon, claiming she is “protecting” Yining from something evil. She threatens to throw the ring down a mineshaft if Yining disobeys, then leaves to attend a grand ball hosted by Prince Zixin at the Palace of Nine Hills.

Yining escapes, buries Little Dragon by the pond, and decides the only way to recover her ring is to go to the palace. Wearing the carp’s gifted clothes, she reaches the gates and slips inside by stealing an invitation scroll.

Guests are tested with an iron tablet meant to reveal magic. Inside the glittering halls, nobles mock her, but Princess Chunlei offers her a measured welcome and assigns a guide.

Yining notices the prince—Zixin—watching, and she recognizes a familiar intensity in him.

Jin appears at the ball and warns Yining to pretend they do not know each other. Yining finds Henglan stealing from guests and forces her to return the ring, but Henglan retaliates by planting a stolen bangle on Yining and loudly accusing her.

Guards drag Yining before Prince Zixin. Yining argues her case, and the princess points out that Yining’s shoes are worth far more than the bangle.

Zixin orders an investigation and has both the bangle and Yining’s ring taken to the treasury until the matter is settled. Refusing to leave without it, Yining bargains to remain in the palace, offering a jeweled shoe as payment.

Zixin allows it, keeps her close in the Pear Blossom Courtyard, and admits he wanted to see her again.

News then spreads: Duke Yuan’s daughter has vanished, taken by a magic-wielder, and the reward for her rescue is starfire—an immensely rare jewel tied to royal power. Political tension spikes as Thorn Valley argues it has treaty rights to handle magic-related threats while Zixin resists outside control.

Plans form for a contest to choose a champion. Meanwhile, Yining’s red mark persists and begins to spread faintly, as if her body is changing.

After a period of preparation and strict court lessons, Yining leaves the palace with Jin and Thorn Valley soldiers on a mission tied to the kidnapping. Along the road, she learns her ring has been moved to Zixin’s private rooms; Jin promises to retrieve it, but his evasions deepen her mistrust.

In Golden Dawn City, Duke Yuan reveals his daughter Ruilin and the family’s starfire were taken, and the kidnapper is believed to be hiding in the Death Swamp. Yining recognizes Ruilin from her dreams, as if some hidden connection is pulling them together.

In the swamp, danger nearly kills Yining, and the group reaches a rose-ringed tower filled with petrified warriors—victims of enchanted music. Yining finds a way to resist the spell and saves Jin, but many soldiers are lost.

They discover Ruilin alive in a rooftop garden, only to learn she fled willingly to escape an arranged marriage and is in love with the witch Dian. The confrontation exposes Jin’s true identity: he is the heir of Thorn Valley, and his people hold secret ties to Mist Island against the Iron Mountains.

Dian possesses the starfire and is searching for something larger than ransom.

When Yining attempts to steal the starfire and escape, conflict erupts again. Her mark flares with light, and Dian reveals she carries an identical ring.

The truth lands hard: Dian is the woman from Yining’s dreams—and likely her sister. Prince Zixin soon captures them, drags them back to the palace, and in prison forces Yining to wear her ring, awakening her magic and confirming she belongs to Mist Island’s lineage.

Zixin recognizes her as the child he once saved, a moment that cost him dearly and shaped his cruelty. He proposes marriage and demands her help in conquering Mist Island, threatening Dian’s life to ensure obedience.

To protect her sister, Yining pretends to agree.

On the day of Zixin’s coronation, betrayal detonates inside the court. Zixin uses a captive Sun Dragon bound within his seal to fuse starfire, killing the creature and triggering chaos.

Princess Chunlei and General Xilu reveal their coup; Zixin collapses from poison, and Chunlei claims the throne. In the turmoil, Thorn Valley attacks, led by Jin, and the palace becomes a battlefield.

Yining uses the Sun Dragon’s lingering gift through her ring, unleashing fire to break doors and free captives. Jin helps her survive the force of that power, while Dian warns it could consume her if she uses it again.

The group escapes the burning palace with Zixin as a weakened captive, pursued through mountain passes. Jin demands repayment for rescue: Yining must help restore Thorn Valley by lending its people magic.

She agrees, trapped by promises and necessity. In Thorn Valley’s enchanted forest, the land itself opens for Jin’s warriors, proving how deep this hidden world runs.

Finally, Yining, Dian, and Ruilin continue toward the sea. Using the ring, Yining opens a misty path of shining lotus steps across the water to Mist Island—her true home—determined to claim her inheritance, protect her sister, and decide for herself what the ring will make of her.

Characters

Yining

Yining begins as a resourceful survivor in Twin Cypress Village, performing “fortunes” she doesn’t believe in because it is safer than honest work under Mistress Henglan’s control. Her defining trait is resistance: she refuses the mines as a fate, refuses humiliation as normal, and refuses to let other people decide what she is worth.

That resistance shows up physically in how she fights—improvising weapons, running, bargaining, stealing when she must—and emotionally in how she protects the few pieces of herself she still trusts, like her handkerchief and the ring. Even when she makes morally gray choices, they come from a clear internal logic: she is trying to reclaim agency in a world where the poor are disposable and the powerful write the rules.

Her growth accelerates once she accepts the ring’s binding magic, because it forces her to confront a terrifying truth: power is not only liberation, it is also a leash. The life-bound condition means she cannot simply discard her inheritance when it becomes inconvenient or frightening, and that tension shapes her later decisions—she hesitates to sever the ring even when it might save her, because she has felt what it is like to be powerless and cannot bear returning to that state.

Across the palace and the Death Swamp, she becomes sharper at reading motives, better at masking fear, and more willing to act strategically, yet she never loses the core compassion that appears in small acts like returning silver to a poor woman. By the end, her “destiny” is not framed as a passive revelation but as something she actively chooses: she steps toward Mist Island not because she is told to, but because she finally understands that her identity has been stolen and buried for years—and she intends to claim it back.

Prince Zixin

Prince Zixin is shaped by inheritance in the harshest sense: he is handed a kingdom, a conquest plan, and a list of tasks by a dying father who values strength over mercy. The royal iron seal becomes both symbol and pressure point—proof of authority, but also a constant reminder that he is expected to expand the Iron Mountains through domination.

He presents himself as composed and assessing at the ball, watching Yining’s movements with the cool attention of someone trained to treat people as potential threats or assets, yet he is also drawn to unpredictability because it breaks the rigid choreography of court.

His most important contradiction is that he once performed a humane act—saving a child—and paid for it in blood and starfire, which turns mercy into a trauma rather than a virtue. That backstory explains why, when he recognizes Yining, he pivots into possessiveness: if kindness once ruined him, then control becomes his substitute for safety.

His cruelty is not random; it is purposeful statecraft, built on the belief that fear is a stable foundation for rule. Even his marriage proposal is framed as policy—power, dominion, conquest—rather than intimacy.

Yet he is not immune to vulnerability: illness, poisoning, betrayal by his sister and his general, and the collapse of his coronation show how fragile “absolute” authority really is. When he protects Yining after she saves him, it is less a moral awakening than a survival recalibration—he realizes her ring is geopolitical leverage, and he cannot afford to lose her.

By the end, as a captive who still vows vengeance, he becomes a living embodiment of the Iron Mountains’ ideology: wounded, furious, and unwilling to relinquish the dream of supremacy.

Jin

Jin enters as a charismatic unknown who treats danger like a game—amused by Yining’s disguises, confident that his status will shield him, and comfortable making debt feel like flirtation. The “favor to be claimed later” reveals his core method: he turns relationships into obligations, not always cruelly, but always deliberately.

Even when he offers kindness—letting her hide in his carriage, bringing honeyed cakes, tending wounds—there is an undertow of calculation because he belongs to a world where alliances are currency and trust is expensive.

As the story unfolds, Jin’s hidden identity as Thorn Valley’s heir reframes his earlier behavior: what looked like casual manipulation is also training, habit, and necessity for someone leading a realm with secrets and enemies. His connection to magic (and the silver, transformed horses) makes him a bridge between the mundane cruelty of the Iron Mountains and the mystical stakes surrounding Mist Island.

He is also a mirror to Yining: both survive by deception, both resent being controlled, and both blur the line between using people and caring about them. His anger at her betrayal over the starfire is revealing because it is not only political—it is personal, the reaction of someone who offered guarded trust and got reminded why he guards it.

By the end, his demand that she help restore Thorn Valley through magic shows his defining flaw and strength at once: he can fight tyranny, but he still believes he can bargain with another person’s power as if it were a resource to allocate. He is not a savior; he is an ally with an agenda.

Mistress Henglan

Mistress Henglan is the story’s most intimate antagonist because her cruelty is domestic, ordinary, and socially protected. She turns guardianship into ownership, keeps Yining financially dependent, and weaponizes shame to shrink her.

Her thefts at the market and at the palace are not just greed; they are her way of asserting power in a world that denies her status, and she takes that power from someone she can easily dominate.

Her most horrifying act—killing Little Dragon and using the ring to do it—reveals a ruthless opportunism: once she realizes magic can be harvested, she treats it like meat and bait. Even her claim that she is “protecting” Yining is a classic abuser’s narrative, reframing harm as care and obedience as safety.

Henglan’s threat to throw the ring down a mineshaft shows she understands exactly where Yining’s weakness is, and she is willing to destroy what she cannot fully control. Functionally, she represents the smaller-scale version of the Iron Mountains’ ideology: the powerful take, the vulnerable endure, and compassion is dismissed as foolishness.

Little Dragon

Little Dragon begins as wonder—an impossible speaking carp in a pond where seasons behave wrongly—and quickly becomes a moral test for Yining. Its bluntness strips away the comforting lies Yining has learned to tell herself, especially the lie that she must tolerate misery to survive.

As a spirit with borrowed magic, Little Dragon is gentle but not sentimental; it offers aid with conditions, forcing Yining to choose responsibility over exploitation when she briefly considers capturing and selling it.

Its greatest narrative role is inheritance made personal. By revealing that Yining’s mother sent it and that the ring is part of Yining’s legacy, Little Dragon turns the ring from a mysterious object into a lineage marker, and the life-bound warning gives that legacy teeth.

The gifts—dress, shoes, hairpin—are not shallow adornment; they are a deliberate attempt to give Yining access to spaces that exclude her. Little Dragon’s death is the emotional hinge of the early story, because it teaches Yining that innocence and magic can be murdered by ordinary cruelty, and that grief can be turned into a plan.

Even after it is gone, its influence persists: Yining’s promise, her burial ritual, and her refusal to let the ring be lost become forms of devotion that keep Little Dragon “alive” as conscience and catalyst.

Dian

Dian is introduced through dread and spectacle—tower roses, petrified warriors, enchanted music—so it is easy to read her as villain, but her character is built from the same raw material as many others: fear of captivity. Her relationship with Ruilin reframes the “kidnapping” into escape, positioning Dian less as a predator and more as someone who offers refuge outside patriarchal arrangements.

She is still dangerous, and she uses poison and illusion without hesitation, which marks her as someone who has survived by making herself terrifying.

The crucial reveal is that Dian shares the same mysterious ring power as Yining and is identified as her sister. That makes her a living answer to Yining’s recurring dreams and a proof that Yining’s past has been hidden rather than erased.

Dian’s choices consistently prioritize freedom—hers, Ruilin’s, later her sister’s—even when that means violence, and she carries a clearer understanding of the cost of magic than Yining initially does. Her warning that the Sun Dragon’s gift can consume Yining shows a protective instinct grounded in experience, not softness.

Dian becomes a guide figure not because she is morally pure, but because she has already walked the road where love, magic, and survival tangle into something sharp.

Lady Ruilin

Lady Ruilin is the story’s clearest example of how “rescue” narratives can conceal coercion. Everyone believes she is a passive victim because that belief serves the political economy of the realms: her disappearance justifies raids, rewards, and heroic contests.

In reality, she runs from an arranged marriage, and her “captivity” is also her rebellion. That choice complicates sympathy—she benefits from privilege, yet that privilege is still a cage when her body and future are treated like bargaining chips.

Ruilin’s importance grows when she becomes a keeper of the starfire pouch and later a fellow prisoner in the palace. She is not as battle-hardened as Yining or Dian, but she is not helpless either; she navigates danger with a different toolset: social awareness, emotional leverage, and the knowledge that powerful men underestimate women who do not wield swords.

Her presence also forces the story to broaden its critique: oppression is not only poverty and mines, it is also nobility’s gilded imprisonment.

Princess Chunlei

Princess Chunlei initially appears as courtly grace—the one who intervenes when Yining is mocked, the royal who can offer protection with a smile. That softness is strategic.

Chunlei understands that appearances are weapons in the palace, and she deploys politeness the way others deploy soldiers. Her “sympathy” for Yining later is revealed as selective and self-serving: she will soothe, but she will not risk herself to truly help.

Her coup is the purest expression of her character. Poisoning her brother with winterfire berries and binding him to the Sun Dragon is not only ambition; it is intimate betrayal executed with patience.

Marrying General Xilu immediately after seizing power shows that she thinks in structures—legitimacy, enforcement, optics—rather than emotions. Chunlei represents a terrifying kind of competence: she is not reckless, she is precise, and she can convert family affection, public ceremony, and military loyalty into a single apparatus of control.

Even when she “spares” Yining, it reads as containment, not mercy.

The Dying King of the Iron Mountains

The dying king is a shadow that still moves the plot after death. He embodies the Iron Mountains’ ideology: wealth extracted from mines, power enforced through military dominance, and legitimacy built on conquest.

By forcing his heir to choose a bride for alliances and to complete tasks before coronation, he reduces succession to a checklist of control, ensuring that the prince inherits not only a crown but also an agenda.

His fixation on enemies associated with magic—Thorn Valley and Mist Island—reveals fear disguised as righteousness. He frames conquest as destiny and strength as virtue, which poisons the next generation’s moral imagination.

Even the chrysanthemum-carved seal, presented as a protective tool, becomes a symbol of how the state treats power: something to clutch always, something that must never be allowed to slip away.

Duke Yuan

Duke Yuan functions as a political father whose personal loss becomes public crisis. His grief is real, but it is immediately absorbed into status and reward: the missing daughter is paired with the stolen starfire, and the rescue becomes a marketplace where warriors compete for wealth and honor.

That setup reflects how nobles turn family events into state opportunities.

Yuan’s mansion, wealth, and portrait of Ruilin emphasize how possession operates in the upper class—children and treasures are displayed, protected, and claimed. Even if he loves his daughter, the arranged marriage he planned is part of the mechanism that drove her to flee, making him both victim and contributor to the system that harms her.

General Xilu

General Xilu represents power without ceremony: the blunt instrument behind the throne. His willingness to accept Chunlei’s claim and crown her marks him as opportunistic, loyal to victory rather than lineage.

By marrying Chunlei immediately, he becomes both her shield and her statement that the new reign is backed by force.

His character highlights a recurring truth in the book’s politics: legitimacy is not only bloodline or ritual, it is whoever controls weapons and the narrative at the same time. Xilu’s role also underscores how quickly ministers and guards switch allegiance when survival depends on it, exposing the palace as a machine that serves strength, not morality.

Minister Luk

Minister Luk appears briefly, but his actions matter because they show how bureaucracy enables flight. Providing travel funds and a jade tablet is not dramatic heroism; it is administrative assistance that can decide whether someone lives.

He reads as pragmatic, someone who understands that proximity to royal power is dangerous and that keeping options open is wise.

His presence also suggests that not everyone within the Iron Mountains is ideologically aligned with conquest; some simply operate within the system, making small choices that can quietly shift outcomes.

Chief Attendant Mai

Chief Attendant Mai embodies palace order: escorts, schedules, rooms, rules, the controlled movement of bodies through space. By managing Yining’s placement in the Pear Blossom Courtyard, Mai becomes one of the mechanisms that make captivity feel like hospitality.

The politeness is real, but it serves surveillance.

Mai’s function is to show how oppression can be made smooth. Chains do not always rattle; sometimes they arrive as etiquette and correct forms of address.

Madam Lau

Madam Lau is the enforcer of refinement, drilling Yining in court etiquette until identity becomes performance. Her training is not merely about manners; it is about reshaping someone’s instincts to fit palace expectations, turning spontaneity into risk and authenticity into liability.

Through her, the book emphasizes that court power is not only held by royals. The people who police behavior, language, and posture help decide who is “acceptable” and who can be discarded.

Shan

Shan, the servant Yining befriends, represents the human warmth that survives in oppressive institutions. Friendship here is not frivolous; it is survival knowledge exchanged quietly, a reminder that servants understand the palace’s true moods because they clean up after them.

Shan’s presence also keeps Yining emotionally tethered to ordinary people, preventing her from becoming fully absorbed into royal games as she gains power.

Mina

Mina is a stylist and messenger, but also a strategist of presentation. By reorganizing Yining’s wardrobe and insisting she must hold the prince’s attention, Mina reveals how the palace treats women’s bodies as political instruments.

Her “help” is conditional: it aims to make Yining useful within Chunlei’s and Zixin’s orbit rather than simply safe.

She embodies a specific kind of court influence—soft control through image, grooming, and social scripting.

Daiyu

Daiyu serves as a guide into court culture and the realm’s geopolitical story, explaining Mist Island’s magic and the palace’s past magical attack. That role makes her a conduit for institutional memory, the kind of knowledge that circulates among attendants and servants even when rulers prefer silence.

She is also part of the palace’s social sorting system: she helps place Yining correctly, reducing the risk that Yining’s ignorance will attract punishment.

Deng

Deng, the talkative soldier traveling with Jin, provides contrast to the otherwise quiet Thorn Valley men. His openness humanizes the group and suggests that loyalty in Thorn Valley includes camaraderie, not only discipline.

Even as a minor figure, he highlights how armies are made of individuals with personalities, not just faceless force, which matters when the story later shows soldiers being petrified and lost.

Mei

Mei, the serving girl in Golden Dawn City, appears in a small exchange that reveals large social truths. Her account of the kidnapping during a storm gives the crisis a lived texture beyond noble proclamations, and Yining’s generous tip shows how Yining instinctively treats working people as peers rather than scenery.

Mei’s role underscores that information travels through service labor, and that those who serve often know more than those who rule.

Farmer Lan

Farmer Lan is a brief but telling figure: a buyer who haggles hard and represents the everyday economy that keeps poor villages running. The negotiation over pears reflects how survival is measured in coins and how easily someone like Yining can be squeezed.

He is not painted as monstrous, just part of a world where scarcity normalizes hard edges.

Songmin

Songmin is the clearest depiction of gendered entitlement at the village level. His attempted assault shows that danger is not only soldiers and princes; it is also the local man who assumes access to a woman’s body because she is isolated and poor.

Yining’s violent resistance marks a key boundary: she will not negotiate her autonomy, even when the world expects her to.

His role is short, but it deepens the story’s theme that domination operates everywhere, not just at the top.

Themes

Power, Corruption, and the Cost of Ambition

In Never Ever After, power operates as both an inheritance and a curse, shaping the destinies of rulers and commoners alike. The Iron Mountains thrive on authority drawn from conquest and control, yet every layer of governance is riddled with greed and decay.

From the dying king’s command that his son dominate neighboring realms to Prince Zixin’s obsessive pursuit of magical supremacy, ambition corrodes morality. The prince’s initial desire to prove himself worthy transforms into a consuming obsession with dominion, eventually leading to betrayal, fratricide, and the loss of humanity.

The symbol of the iron seal — cold, unyielding, and heavy — embodies this corruption: power forged not through wisdom or compassion but through violence and subjugation. In contrast, Yining’s relationship with power is reluctant and intimate, born from survival rather than conquest.

Her magical ring, linked to life and death, presents a different form of authority — one rooted in empathy and natural energy rather than iron and war. The novel explores how structures of rule thrive on extraction, whether it is ore from the mines, life from magical beings, or obedience from subjects.

Even those who resist are drawn into its logic; Yining herself begins to grasp that wielding power without self-awareness mirrors the cruelty she despises. The story becomes a meditation on how ambition, if unchecked, deforms the human spirit — transforming protectors into tyrants and love into leverage.

Ultimately, the book presents power not as liberation but as a burden that demands sacrifice, forcing each character to decide what they are willing to destroy in order to hold it.

Identity, Heritage, and Transformation

The question of who one truly is lies at the heart of Never Ever After, driving both the protagonist’s personal struggle and the broader conflicts between kingdoms. Yining begins as a nameless girl surviving through deceit, unaware of her magical lineage and the world that shaped her.

Her transformation from a street fortune-teller to a figure of immense mystical potential is not merely about gaining strength but about reclaiming a fragmented identity. The wooden ring, later revealed to be bound to her essence, represents the unbroken line between her forgotten past and her destined self.

Each revelation — from the carp spirit’s connection to her mother, to her sister Dian’s existence, to her own half-human, half-magic nature — strips away layers of falsehood imposed by society, family, and fear. Identity here is fluid, evolving through betrayal, compassion, and memory.

The story suggests that heritage is not just bloodline but the moral and emotional inheritance of choices made before one’s birth. The contrast between Yining’s humble origins and her magical power challenges the rigid hierarchies of the Iron Mountains, questioning who deserves to lead and why.

Her eventual acceptance of both her human and supernatural halves becomes an act of defiance against systems that demand purity, loyalty, or submission. The metamorphosis motif — from carp to dragon, from girl to power-bearer — mirrors her own evolution: identity is not static but earned through suffering and understanding.

Through Yining, the novel asserts that knowing oneself is the most perilous and redemptive journey of all.

Betrayal and Loyalty

Throughout Never Ever After, loyalty exists as a fragile currency constantly bartered, broken, and redefined. Trust between characters is repeatedly tested — Yining’s guardian betrays her for greed, Jin conceals his true identity as a prince, and Zixin’s sister poisons him to seize the throne.

Every alliance in the narrative carries an undercurrent of deception, suggesting that loyalty in a world built on ambition is always conditional. Yet the story also portrays moments of quiet fidelity that restore meaning amid chaos: Yining burying Little Dragon, risking herself to save others, and refusing to abandon her sister even after years of manipulation.

These gestures contrast starkly with the treacheries of royal courts and highlight that loyalty, in its purest form, requires selflessness. Betrayal, however, becomes the necessary engine of change — each act of deceit reveals hidden truths or forces characters to confront their illusions.

Jin’s betrayal, for instance, exposes the political duplicity of Thorn Valley but also reveals his conflicted love for Yining. Even Zixin’s cruelty carries the ghost of loyalty twisted by fear and legacy.

The novel’s moral vision suggests that betrayal is not the opposite of loyalty but its inevitable companion; one cannot exist without the risk of the other. In the end, Yining’s greatest loyalty is to her own conscience — a loyalty that transcends allegiance to any kingdom or person.

Through this tension, the narrative examines the painful cost of trust in a world where love and treachery often speak the same language.

Freedom, Choice, and Fate

Freedom in Never Ever After is constantly negotiated between destiny and defiance. Yining’s journey begins in captivity — first under the authority of her aunt, later within the palace, and finally under the weight of her own magic.

Each stage presents the illusion of choice within invisible boundaries. The dying king’s command to his son, the arranged marriages, and the divine marks binding magic-wielders all demonstrate how fate manipulates mortal lives.

Yet, through Yining’s repeated acts of rebellion — escaping arrest, refusing royal decrees, and claiming agency over her power — the story asserts that freedom is not granted but seized. The carp’s gift of the ring initially appears as destiny fulfilled, but it becomes meaningful only when Yining decides to accept and bear its cost.

This decision echoes throughout the novel as she continuously resists being shaped by others’ expectations, whether as a pawn in royal politics or as a vessel of ancient magic. Her defiance is mirrored in Dian’s choice to love across forbidden lines and in Ruilin’s refusal to live as a political ornament.

Fate operates as both chain and compass; it directs but does not dictate. The novel questions whether freedom can ever exist in a world governed by prophecy, blood, and power, ultimately concluding that true liberation lies not in escaping destiny but in reshaping its meaning.

By the final act, when Yining steps across the sea toward Mist Island, she embodies the paradox of freedom: to choose one’s fate is to embrace both its pain and its promise.

Love, Sacrifice, and Redemption

Love in Never Ever After is rarely gentle; it is a force that wounds as deeply as it heals. Romantic affection, familial devotion, and spiritual connection all demand sacrifice.

Yining’s affection for Jin is entangled with mistrust, lies, and conflicting loyalties, reflecting how intimacy becomes dangerous in a world obsessed with power. Her bond with Little Dragon captures a purer form of love — rooted in trust, empathy, and transformation — that contrasts sharply with the manipulative relationships of the court.

The carp’s death, consumed by human greed, becomes Yining’s first confrontation with the cost of love: that to care deeply is to risk destruction. Similarly, the complex love between Dian and Ruilin challenges societal expectations, presenting devotion as rebellion.

Even Zixin’s corrupted affection for Yining — possessive and coercive — underscores love’s potential to imprison rather than liberate. Yet amid all betrayals, love remains the only path toward redemption.

Yining’s final act of saving Zixin despite his cruelty reclaims love from the realm of power and turns it into grace. Sacrifice, then, becomes the true measure of affection, not grand declarations but the willingness to endure loss.

Through love’s many forms, the novel portrays redemption not as forgiveness from others but as an inward reckoning — the courage to confront one’s failures and still choose compassion. In the end, Yining’s love, scarred but steadfast, transforms from a personal emotion into a universal force of renewal, guiding her toward Mist Island and the promise of beginning again.