O Sinners! Summary, Characters and Themes

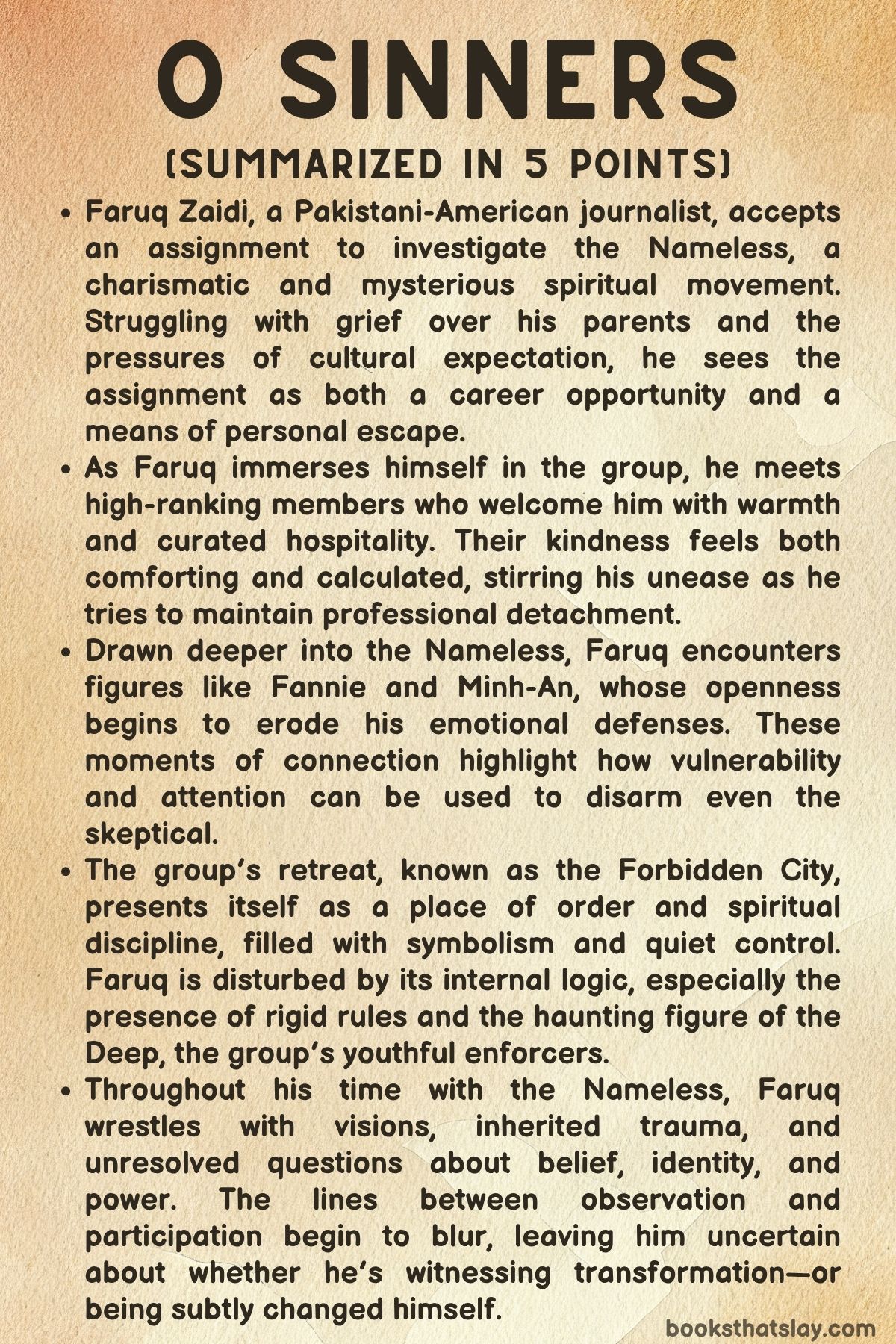

O Sinners! by Nicole Cuffy is a bold, lyrical novel that straddles personal trauma, cultural inheritance, and the murky seduction of belief. Through the story of Faruq Zaidi—a Pakistani-American journalist burdened by grief, race, and legacy—it explores the vulnerable spaces where pain meets performance, and where spiritual longing opens the door to manipulation.

Faruq’s encounter with a group called the Nameless, and its magnetic leader Odo, serves as both a professional investigation and a deeply emotional confrontation with the past. Cuffy pairs this with vivid depictions of the Vietnam War, crafting a dual timeline that bridges generations through trauma, ideology, and transformation.

Summary

Faruq Zaidi begins his story in cold, urban isolation—his early morning run along a frozen East River mirroring his internal numbness. He lives in a Brooklyn brownstone heavy with memories of his deceased parents.

His cat, Muezza, offers sparse comfort, and his Auntie Naila insists on overstepping boundaries in a way that amplifies his loneliness. Faruq is a respected journalist at a New York arts and culture magazine, where he finds some stability and camaraderie.

Anita, his editor and mentor, offers him a strange but enticing assignment: investigate a spiritual movement called the Nameless. Led by the elusive Odo, the group skirts the boundary between cult and collective.

Anita frames the assignment as a mix of journalism and sabbatical—a chance to recover from the emotional stagnation Faruq has been suffering since his father’s death.

Intrigued and wary, Faruq meets Quiver, a wealthy convert who introduces him to the group’s philosophy of renunciation and rebirth. Their ideology is steeped in performance and aesthetic, mixing spiritual abstraction with visual pageantry.

The group avoids labels and embraces an amorphous collective identity. Their ideas echo cult dynamics but remain cloaked in the language of healing and personal evolution.

Faruq is drawn into their mystique gradually, even as he notices warning signs. Multimedia snippets—sermons, videos, interviews—interrupted throughout the narrative deepen the sense of unreliability and blurred truth.

These materials offer conflicting portraits of Odo: some see him as a prophet, others as a dangerous narcissist.

The narrative then splits, shifting periodically to the jungles of Vietnam, where a group of Black American soldiers—Preach, Silk, Crazy Horse, Bigger—struggle through racial tension, extreme conditions, and emotional suppression. These soldiers, bound by a complicated brotherhood, use humor and faith to survive.

Preach, spiritual and self-contained, dies quietly after a brutal ambush and failed rescue. His death is unceremonious but emotionally heavy.

A fevered vision of his mother appears at the end, casting his final moments in surreal light. These war sequences act as both historical reflection and symbolic mirror, linking themes of masculinity, trauma, and transformation.

Back in the present, Faruq travels to California and finds himself in the luxurious home of Clover and Aeschylus, high-ranking Nameless members. Their hospitality is calculated and performative.

He feels watched, tested, and subtly evaluated. As he accompanies them to volunteer shifts and art installations, he begins to understand the group’s values: curated authenticity, hyper-conscious aesthetics, and moral pageantry.

At a mansion gathering, he meets Fannie, who recounts disowning her family under Odo’s instruction. Her softness and candor create intimacy, but also feel manipulative.

Faruq begins to confess, opening up about his estranged family, his faith, and his grief.

He is then taken to the Forbidden City, the Nameless retreat compound deep in the redwoods. It is a world of strict order and mystical ambiance.

Adam, a serene and androgynous engineer, introduces him to its doctrines and design. The Deep—a group of youthful enforcers in black—guard the compound and embody the Nameless creed through their devotion to the “18 Utterances.

” The boundaries between observer and participant start to collapse. Faruq sees a shadowy wolf during his runs, experiences déjà vu, and begins to question his grip on reality.

The Nameless’s ideology increasingly resonates with the unspoken grief, rage, and inherited shame that Faruq has long suppressed.

He finally meets Odo, who is unexpectedly ordinary and charismatic, not sinister. Their meeting is informal, grounded in physicality and presence rather than doctrine.

Odo’s philosophy—where the divine arrives like a dawn, slow and undeniable—triggers Faruq’s confusion and reluctant respect. Minh-An, a dying follower, draws Faruq further in by waking him to witness the birth of a foal named Cora.

He participates in the delivery, and the moment is intimate, raw, and humbling. Minh-An calls it “bearing witness,” suggesting that presence is a form of devotion.

Faruq is changed by this event—less through belief than through embodied experience.

The Vietnam thread grows more mystical. Bigger, a soldier haunted by guilt, dies and is metaphorically reborn as a tiger, tying into the surreal animal visions seen in the Nameless retreat.

Preach’s death, Silk’s slow fade, and Crazy Horse’s explosive grief echo through time, with the jungle acting as a crucible for spiritual transformation. Odo later reflects on a jungle encounter with elephants and a tiger, suggesting he may have once been Crazy Horse, linking past violence to his spiritual awakening.

Faruq’s increasing absorption in the Nameless reaches a climax during a meditative reenactment that mirrors his mother’s death by exorcism. Overcome with rage, he snaps, disrupting the ritual and exposing the undercurrent of trauma masquerading as enlightenment.

The mostly white followers react with fear, racializing his anger. The illusion of spiritual liberation crumbles.

He denounces Odo and flees, but Minh-An’s death pulls him back emotionally. Despite his anger, he mourns her with sincerity.

In a final confrontation, Odo tries to reclaim Faruq. Faruq resists, finally expressing his rage through a primal scream—an act of rebellion and release.

Back in Brooklyn, he smashes a wall in his father’s home, symbolizing the breaking of generational silence and repression. He begins to write again.

Whether he will publish the story is unclear. What is certain is that he has claimed his voice.

O Sinners is not just about cults or war; it is about how grief and trauma become vessels for belief, and how the desperate search for meaning can make even the most skeptical vulnerable to seduction. In war, in faith, in family, and in love, the story reminds us: the only escape is through honesty, and the only redemption lies in bearing witness.

Characters

Faruq Zaidi

Faruq Zaidi is the central figure in O Sinners, a Pakistani-American journalist whose internal and external journeys shape the emotional and philosophical core of the novel. As an ex-Muslim man of color living in post-9/11 New York, Faruq grapples with the weight of cultural inheritance, the trauma of personal loss, and the alienation of navigating predominantly white, secular spaces.

His stoicism masks a deeply fractured inner life: the early loss of his mother—implied to be the result of a failed religious exorcism—and the death of his father leave him tethered to a past filled with silence, repression, and unresolved grief. Faruq’s assignment to report on the Nameless starts as a professional endeavor but evolves into a spiritual and emotional reckoning.

His acute awareness of power dynamics—racial, spiritual, and emotional—makes him resistant to the Nameless’s seductive intimacy, but not immune. Moments such as delivering a foal or meditating beside cult members complicate his binary notions of manipulation versus authenticity.

Faruq is haunted—by literal visions, by inherited trauma, and by questions of belonging. Whether confronting Odo, rejecting performative spirituality, or destroying the wall in his father’s home, Faruq ultimately embodies the painful process of liberation through unflinching confrontation with memory, identity, and myth.

Odo

Odo is the enigmatic leader of the Nameless, a spiritual collective that blurs the boundaries between liberation and indoctrination. His charisma is deliberately understated: he presents as approachable, warm, and physically unremarkable, which disarms expectations of authoritarian cult figures.

Yet beneath his serene surface lies an intensely manipulative power. Odo’s philosophy centers around the rejection of ego, the embrace of “Other Sight,” and the belief that true revelation arrives not as a blinding vision but as an inevitable dawn.

He speaks in aphorisms, preaches intimacy, and fosters a culture of deep emotional and spiritual immersion that masks authoritarian control. His past, hinted to be linked with the Vietnam War and possibly as the soldier known as Crazy Horse, reveals a personal trauma that morphed into a messianic identity.

Odo’s teachings resonate with followers like Minh-An, who see him as a soulmate and liberator, but for Faruq, he becomes the locus of unease—a figure who exploits vulnerability under the guise of healing. Odo’s brilliance lies in how he mirrors back his followers’ desires and fears, shaping himself into whatever they need.

He is neither fully monster nor saint, but a reflection of the longing and loss that fuels spiritual surrender.

Minh-An

Minh-An, a terminally ill devotee of the Nameless, embodies both the sincerity and tragedy of blind faith. She is deeply loyal to Odo and believes herself to be spiritually “seen” and completed by him.

Her bond with Faruq is intimate and confessional; she draws him into rituals, philosophical conversations, and the witnessing of symbolic acts like the birth of a foal named Cora. Minh-An speaks in mystical metaphors—glass shattering, cosmic unity—and is emotionally articulate about the power of being recognized in her true self.

Yet her certainty is also her fragility. She is a believer shaped by loss and illness, her devotion a coping mechanism for both her mortality and her unresolved past.

Her death acts as a catalyst for Faruq’s disillusionment; he mourns her not just as a person but as a lost possibility of sincerity within the Nameless. Through Minh-An, the novel explores how spiritual communities can offer meaning and connection to the most vulnerable, while also underscoring the high emotional stakes of surrendering to belief.

Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse is a central figure in the Vietnam War strand of the narrative, a soldier whose rage, trauma, and mythic presence echo through the novel’s spiritual and psychological arcs. He is volatile and haunted, a man shaped by violence but not entirely consumed by it.

His close bond with Silk and his experiences in the jungle—particularly the surreal tiger and elephant scene—become pivotal moments of transformation. The implication that Crazy Horse eventually becomes Odo ties the novel’s temporal layers into a cohesive philosophical arc: trauma becomes transcendence, war mutates into revelation.

Crazy Horse’s fury, described as pythonic and possessive, symbolizes a liminal state between life and death, between man and beast, between past self and mythic rebirth. His embodiment of post-war alienation makes him both a victim and an architect of the manipulative salvation he later offers others as Odo.

Silk

Silk is Crazy Horse’s closest companion in the Vietnam narrative, a soldier who balances gallows humor with stoic endurance. His fatalism does not preclude love or loyalty—he remains present and emotionally grounded despite the surrounding chaos.

Silk’s final moments, marked by tender banter and physical collapse, highlight the brutal humanity of soldiers forced into absurd survival. He is a vessel of pathos, a figure who sees the farce and tragedy of war but continues to move through it with dark grace.

His death deeply wounds Crazy Horse, catalyzing the transformative breakdown that eventually leads to spiritual metamorphosis. Silk’s character is a poignant reminder that even in war, camaraderie can offer moments of truth and emotional sustenance, no matter how fleeting.

Preach

Preach is another key figure in the Vietnam narrative, a deeply spiritual Black soldier whose quiet dignity and inner strength distinguish him from his peers. Nearing the end of his tour, Preach carries himself with calm detachment, forming a subtle and poignant connection with Brother Ned, a white soldier.

His death—after saving Crazy Horse and succumbing to exhaustion—is quiet, even invisible. Yet it resonates thematically as an expression of the often-unrecognized burdens Black men carry in hostile systems.

His dying vision of his mother exorcising his demons with guava seeds is one of the novel’s most haunting images, linking personal suffering to generational and cultural trauma. Preach’s life and death foreshadow Faruq’s spiritual crisis, forming a connective tissue between past and present, soldier and seeker.

Bigger

Bigger’s presence at the novel’s outset sets the tone for its surreal and metaphysical undercurrent. Fevered, guilt-ridden, and lost in hallucinations, he believes himself responsible for the deaths of fellow soldiers and ultimately dies in a state of spiritual dissociation.

His transformation—symbolic or literal—into a tiger encapsulates the narrative’s constant dance between metaphor and mythology. Bigger is a figure of fractured consciousness, a prelude to the spiritual fragmentation and reintegration that other characters, particularly Crazy Horse and Faruq, must undergo.

He represents the cost of unprocessed guilt and the fragility of the mind under extreme pressure.

Anita

Anita, Faruq’s editor and mentor, is a grounding presence in the early part of the novel. She provides him with the assignment to investigate the Nameless, framing it as a sabbatical of sorts to heal from his grief.

While not a central character in terms of page time, Anita represents a tether to Faruq’s professional life and a version of himself not yet subsumed by spiritual confusion. Her editorial guidance, along with her emotional steadiness, contrasts sharply with the seductive chaos of the Nameless, highlighting the world Faruq is drifting away from.

Auntie Naila

Auntie Naila is Faruq’s meddling but well-meaning relative, a woman who represents both the warmth and claustrophobia of familial obligation. Her inability to respect Faruq’s autonomy—while coming from a place of love—mirrors the invasive intimacy of the Nameless.

Naila embodies the tension between care and control, tradition and independence. Her presence in the novel underscores how even familial love can be infused with judgment, expectation, and the quiet violence of not being seen for who one truly is.

Fannie

Fannie is a member of the Nameless whose flirtatious warmth and emotional openness draw Faruq into the community’s seductive allure. Her conversation with him—centered on her choice to sever ties with her family—is presented as an act of self-actualization but also reveals the manipulative emotional logic of the cult.

Fannie blurs the line between freedom and indoctrination, offering Faruq a vision of vulnerability that is both genuine and rehearsed. Her character exemplifies how the Nameless fosters intimacy as a tool of conversion, weaponizing emotional exposure to dissolve skepticism.

Adam

Adam is the serene, androgynous engineer who welcomes Faruq to the Nameless’s Forbidden City. His presence is unnervingly calm, a personification of the cult’s aestheticized discipline.

Adam explains the rules, rituals, and architectural philosophy of the community with the detached confidence of someone fully immersed in the ideology. He is both guide and gatekeeper, embodying the seductive normalcy of cult life.

Through Adam, the novel illustrates how radical belief systems can package themselves in the language of beauty, structure, and serene order—masking coercion with grace.

Muezza

Though a cat, Muezza plays a symbolic role in Faruq’s story. A quiet, constant companion in a life riddled with loss and uncertainty, Muezza represents ritual, affection, and the last threads of normalcy.

Named after the Prophet Muhammad’s beloved cat, Muezza also carries spiritual significance—perhaps unintentionally, but tellingly—reminding readers of Faruq’s complex relationship with religion and tradition. In a novel filled with symbolic births, deaths, and mythological animals, Muezza’s mundane presence is a tender anchor to reality.

Themes

Identity and the Performance of Self

Faruq’s journey through O Sinners is fundamentally shaped by a persistent tension between how he sees himself and how others interpret or misinterpret that identity. As a Pakistani-American ex-Muslim man in post-9/11 America, he is subjected to a constant external gaze, where his body, religion, and racial background are politicized and scrutinized regardless of his intentions.

This surveillance is not merely governmental or institutional; it is deeply social and interpersonal. Even within the supposedly liberating space of the Nameless, Faruq is still viewed as a curiosity, sometimes revered and sometimes feared.

His anger, when expressed, is quickly pathologized, revealing how society projects danger onto racialized bodies. He is never permitted full neutrality—every expression is interpreted through a politicized lens.

What complicates this theme further is Faruq’s own ambivalence about his cultural and religious background. He carries his mother’s scarf, a potent symbol of both love and the religious expectations that haunted her life and contributed to her suffering.

His spiritual unease is not just a rejection of Islam, but a broader uncertainty about all systems that demand submission, whether doctrinal or secular. At work, he performs competence and composure; in the Nameless, he experiments with vulnerability and receptiveness.

Yet neither space offers him full authenticity. The cult’s openness is revealed to be a performance as calculated as any newsroom editorial meeting.

Faruq’s inner conflict lies in not knowing where his true self ends and where the roles assigned to him—by family, nation, faith, and profession—begin. Ultimately, the novel questions whether identity is ever a fixed truth or only a temporary alignment of perception and desire.

Grief as a Portal to Transformation

Grief in O Sinners is not a singular event but a lingering, transformative presence that defines the rhythm of Faruq’s life. His mother’s death, potentially by suicide after a failed exorcism, is a wound that reverberates across his decisions, relationships, and self-concept.

Her absence is not just emotional—it is ontological. It shapes how Faruq perceives the limits of love, the dangers of blind faith, and the burdens of cultural inheritance.

Her final act, interpreted by some as madness and by others as martyrdom, becomes a source of unresolved guilt for Faruq. His internalized grief manifests in fragmented dreams, surreal hallucinations, and his compulsive need to bear witness—to death, to birth, to pain—perhaps in the hope that witnessing might offer salvation where intervention failed.

This grief is mirrored in the deaths that populate the narrative’s Vietnam thread—particularly that of Preach and Silk—and also Minh-An’s demise in the cult timeline. The text repeatedly links grief to a threshold moment, where those left behind are either paralyzed by it or forced into a kind of rebirth.

Faruq’s exposure to the rawness of other people’s sorrow, such as Minh-An’s dying hope or the soldiers’ trauma, forces him to confront the fact that grief is not something to be conquered. It must be carried, shaped, and perhaps even revered.

By the novel’s end, grief becomes both a chain and a key—it binds Faruq to the past but also unlocks his potential for agency, protest, and, tentatively, healing.

Charisma and the Seduction of Belonging

Odo’s leadership of the Nameless is a study in how charisma, when coupled with a language of liberation, can become a tool for manipulation. Faruq is initially skeptical, but he gradually becomes fascinated—not just by Odo’s philosophy, but by how the entire community orbits his presence.

The group’s rituals, the aesthetic harmony of their spaces, and their unwavering attentiveness seduce Faruq with promises of meaning and inclusion. He is not merely being investigated for possible recruitment; he is being reprogrammed to associate love, care, and spiritual revelation with Odo’s authority.

The effect is gradual, insidious, and largely psychological. The cult does not demand immediate obedience—it demands emotional disclosure, communal vulnerability, and a slow dismantling of skepticism.

Faruq’s encounters with members like Fannie and Minh-An underscore how the language of belonging—terms like “soulmate,” “witness,” and “release”—is weaponized in the name of spiritual progress. Yet these interactions also raise troubling questions about consent, choice, and authenticity.

The cult’s appeal lies in its soft coercion, where affection is conflated with ideology and doubt is recast as trauma yet to be healed. Faruq, already burdened by loneliness, cultural displacement, and suppressed grief, is uniquely susceptible to this environment.

The narrative suggests that belonging, while essential, becomes dangerous when it is conditioned upon submission to a singular vision. Odo’s power lies not just in his beliefs but in his ability to make his followers believe they chose those beliefs themselves.

This theme unravels how charismatic systems replace personal agency with collective identity and disguise erasure as empowerment.

War, Brotherhood, and the Inheritance of Pain

The Vietnam War subplot in O Sinners operates not as a historical aside but as a mirror and precursor to the spiritual and emotional conflicts in the present-day narrative. Through the experiences of Bigger, Silk, Preach, and Crazy Horse, the novel explores how extreme conditions produce both brutalization and brotherhood.

These soldiers, largely Black, navigate the daily terror of combat with humor, loyalty, and a kind of fatalistic grace. Their dialogue is peppered with gallows humor, superstition, and philosophical musings about survival and purpose.

Yet the war also consumes them: Bigger succumbs to fever and hallucination, Preach dies quietly after an act of heroism, and Silk is mortally wounded in a futile attempt to save others. Their fates are not heroic in the traditional sense—they are quiet, ambiguous, and laden with sorrow.

What links this war narrative to Faruq’s investigation is the suggestion that trauma is transhistorical. The pain carried by Crazy Horse—who later becomes Odo—is not simply personal but ancestral.

His metamorphosis from soldier to spiritual leader is framed as a response to horror, a way to metabolize suffering into doctrine. The war becomes a crucible for mythmaking, and Odo’s later teachings about ego death and cosmic clarity are built atop the ruins of Silk’s corpse and Bigger’s tiger hallucination.

In this light, the cult’s ideology is not merely fanciful but forged from real loss. The theme underscores that the inheritance of pain is cyclical.

Faruq, haunted by his mother’s anguish and his own racialized body, steps into a system built by another traumatized man. War, both literal and emotional, becomes the seedbed for spiritual extremism.

Surveillance, Spectacle, and the Politics of Visibility

Throughout O Sinners, the idea of being watched—by strangers, by institutions, by spiritual leaders—becomes a recurring motif that undercuts any possibility of privacy or neutrality. Faruq’s career as a journalist places him in the role of observer, but he is never outside the gaze himself.

From his early sense of being followed in JFK airport to the performative rituals within the Nameless compound, he is constantly navigating a world that conflates visibility with value. His race, profession, and outsider status make him hyper-visible in some contexts and invisible in others.

The group’s “Deep,” with their aesthetic uniformity and reverence for the “18 Utterances,” functions as both enforcers and surveillance agents, silently communicating that conformity is a form of safety.

The cult’s public events, their curated architecture, and their obsession with physical poise all feed into a larger spectacle that demands both attention and submission. Faruq’s suspicion grows when he realizes that even moments of intimacy—his conversation with Fannie, his emotional outbursts, his spontaneous participation in rituals—may have been engineered or at least anticipated.

The reader is left to question whether Faruq is observing or performing, resisting or complying. This tension reflects broader anxieties about identity in the digital and post-9/11 era, where Muslim men, in particular, are disproportionately subject to surveillance and suspicion.

In O Sinners, visibility is never neutral; it is a site of control, vulnerability, and ideological entrapment. Faruq’s eventual act of defiance is not just a rejection of the cult but a reclamation of his right to be unseen, to mourn and exist without spectacle.