Rules for Fake Girlfriend Summary, Characters and Themes

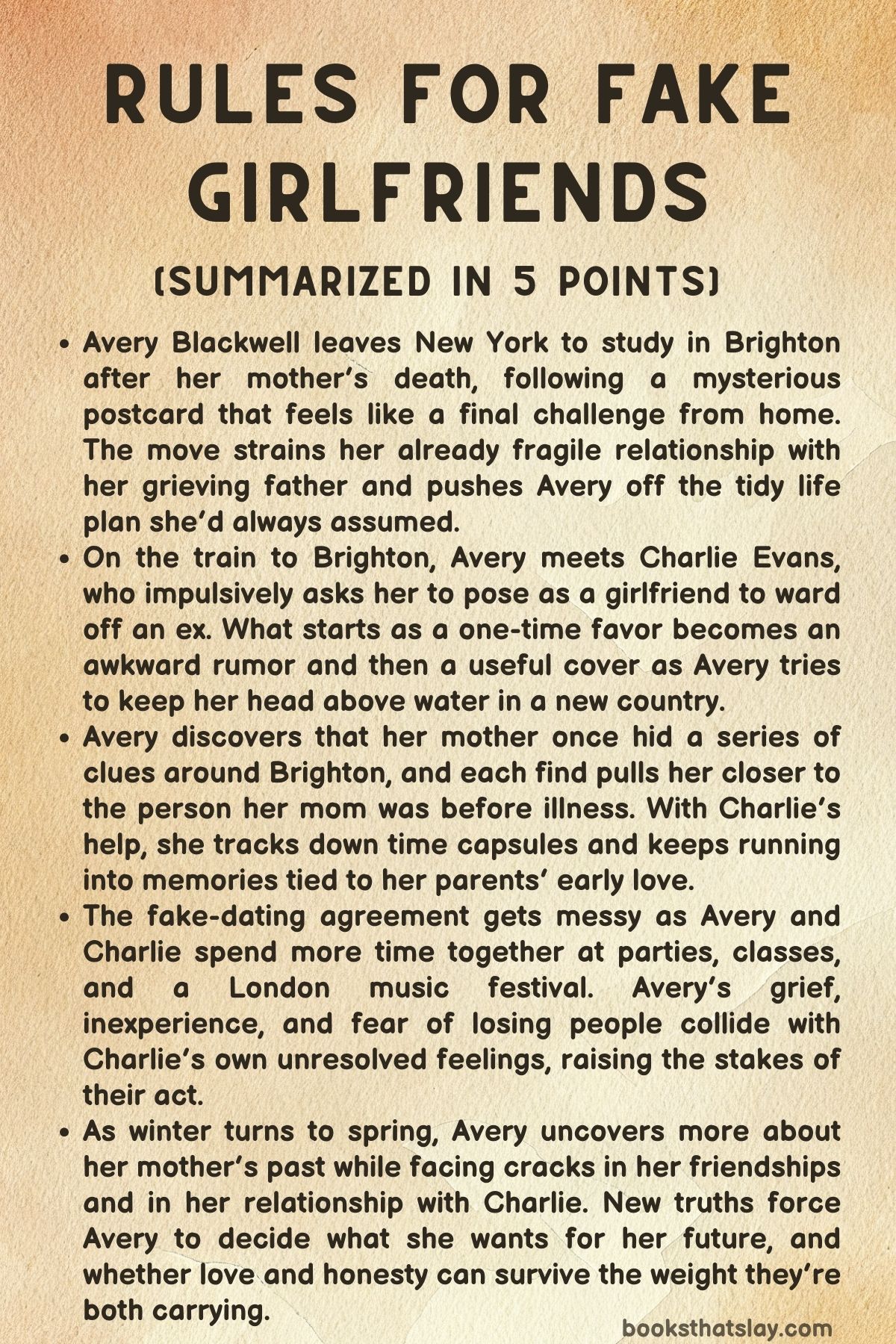

Rules for Fake Girlfriends by Raegan Revord is a contemporary YA romance set against a bittersweet coming-of-age backdrop. After losing her mother, Avery Blackwell postpones her perfect Columbia-to-med-school plan and moves from New York to Brighton, England, chasing a final scavenger hunt her mom designed years ago.

On the way, Avery meets Charlie Evans, a witty local still hung up on her ex. A harmless pretend-girlfriend moment on a train turns into a month-long fake-dating pact that collides with grief, first love, and the messy truth of what people hide to protect each other.

Summary

Avery Blackwell is packing up her New York life in the sticky August heat, trying not to unravel while her cat, Circe, lounges on her suitcase. Three months ago her mother, Halle, died after a long battle with lung cancer, and Avery’s world is stuck in a cycle of numbness and anger.

Her father, Evan, is slipping into depression and quietly clearing their apartment of Halle’s light-painting photographs. Each missing picture feels like another goodbye Avery didn’t agree to.

The night before Avery leaves, their dinner is strained, and Evan dodges her questions about the empty walls, pushing her instead toward the medical future she once promised. Avery goes to bed feeling like home has turned into a place where grief is handled by erasing it.

For years Avery had one path: top grades, Columbia for biology, medical school, then oncology, because she wanted to fight the disease that took her mother. But two months earlier a postcard from Halle arrived after her death.

It wasn’t a normal goodbye. Halle wrote like she always did during her scavenger hunts, telling Avery not to cling to achievements and urging her to take a risk.

The postcard said Avery could only finish their story in Brighton, where Halle grew up and went to college. Avery took it as a final request and a final game, so she deferred Columbia for a year, enrolled at Brighton College, and flew out, even though part of her fears she’s making a grief-driven mistake.

On departure morning, Avery wavers, but her best friend Amira and Amira’s mom Carmen get her to the airport. Evan stays behind under the excuse of work, and their goodbye is awkward and unfinished.

Avery reaches England alone, then takes a train to Brighton. On that packed train she meets Charlie Evans, a fast-talking British girl who slides into the seat beside her, praises her Oasis shirt, and acts like they’ve been friends for years.

When Charlie spots her ex-girlfriend Leyla in the aisle, she panics and begs Avery to pretend they’re dating. Avery, caught off guard, plays along.

Charlie grabs her hand and leans on her shoulder until Leyla walks away. The act lasts only minutes, but Avery is startled by how safe and easy it feels to talk to someone who knows nothing about her loss.

Brighton is bright, salty, and unfamiliar. Avery moves into a student flat with Maddi Newton, a Welsh fine-art major who loves Avery’s chaotic thrift-store decorating.

Their strict resident director, Demi, warns Avery about noise, pets, and fees, glaring at Circe. On campus Avery meets Esther Evans, an administrator organizing a reunion for the class of 2000.

During the freshman tour, one of the student guides turns out to be Charlie—who is also Esther’s daughter. Over coffee, Avery explains the postcard and the word “manifest.

” Esther reveals she and Halle were roommates and close friends, and suggests Halle may have left a time capsule, a graduating-class tradition. Charlie takes Avery to the library’s older stacks and shows her a display holding one of Halle’s light paintings titled “Manifest, 2000.

” The photo spells “CORA” in light. The clue hits Avery hard; it proves the hunt is real.

She bolts, then later texts Charlie an apology for running.

Classes begin. Avery sticks to biology but adds creative writing to honor her mom’s artistic side.

Rumors spread that she and Charlie are dating because of the train scene. Charlie jokes they might need to keep up the story, especially since they end up assigned as lab partners.

Charlie researches “CORA” and thinks it points to a local tarot reader. Avery agrees to go with her.

They find Cora’s tiny green shop tucked near a quirky marketplace. Avery means to ask about her mother’s capsule, but instead asks for a reading.

Cora’s cards for Charlie hint at upheaval and a romantic crossroads, while Avery’s cards speak plainly of grief, limbo, and the need for balance. Then Cora drops the performance, says she knows exactly who Avery is, and produces Halle’s blue metal time-capsule cylinder, kept sealed at Halle’s request for twenty years.

Inside is a postcard labeled “AVERY,” and a message explaining this is only the first step in a hunt Halle hoped to share with her daughter one day. Avery realizes there are six more clues out there.

The discovery overwhelms her; she runs to the rocky beach and breaks down. Charlie follows, holds her, and listens.

Leyla appears with friends, assumes Avery and Charlie are a couple, and invites them to a party and a London music festival. Afterward Avery offers to help Charlie by fake-dating in public for a month to make Leyla jealous.

Charlie agrees, thrilled, and in exchange promises to help Avery track the scavenger hunt. At Leyla’s party Avery commits to the act, inventing a cute meet-story on the spot.

Leyla is friendly rather than rattled, and Avery notices how much Charlie still lights up around her ex, which makes Avery uneasy in ways she doesn’t yet name.

The hunt continues. They follow the next clue to Record Galleries, where Halle worked in college.

The owner, Teddie, gives Avery another capsule holding a postcard of a mossy heart-shaped boulder labeled “Kiss,” marking the spot where Halle and Evan shared their first kiss. With help from Colin—a friendly student who uses a cane—they find the Heart Stone in the countryside, dig up another capsule, and discover a floppy disk inside.

When the disk cracks in Avery’s hands, she collapses into despair, sure she has ruined everything. Charlie holds her again, refusing to let Avery call the hunt over.

Meanwhile, the fake relationship starts to feel less fake. After watching Maddi perform in Electra, Charlie suggests they celebrate their one-month “anniversary.

” Avery snaps at her in front of Leyla to keep the jealousy plan on track, and Charlie is hurt. On the train to London for the festival, Avery keeps up the cold routine for Leyla’s benefit, but it strains everyone.

Maddi corners Avery in the bathroom and bluntly says she’s falling for Charlie.

In London, Charlie gives Avery a day that looks exactly like a real date—museums, laughter, hand-holding, dancing to “Wonderwall. ” At the Oasis cover-band show, Charlie pulls Avery onstage and kisses her in front of the crowd, tossing the plan aside.

Avery kisses back. After that, they become an actual couple.

Avery feels alive again, her grades rise, her writing blooms, and she invites Charlie to spend winter break in New York. Charlie agrees.

Then things crack. Amira, seeing the viral kiss video, calls furious that Avery hid the relationship, and they fight.

Avery later spots Charlie and Leyla holding hands on a bench, hears Leyla urging Charlie to “tell her,” and spirals. Charlie cancels New York, claiming her aunt is ill.

Avery flies home alone, only to find Evan deep in contamination rituals and still stripping Halle’s work from their apartment. The clash ends with Avery discovering Halle’s photos stored safely at her old gallery, along with a backup clue that restores Avery’s determination to return to Brighton.

Back at school, Avery senses Charlie is still hiding something. During spring break, Avery finds a capsule at a flea market holding a light-painting postcard labeled “Yes.

” Esther explains it marks the moment Halle accepted Evan’s proposal in Brighton, and Avery realizes Charlie has been lying about her absences. She confronts Charlie, assumes Leyla is the reason, and breaks up with her.

A trip to Cornwall with Colin, Maddi, and Rowan helps Avery breathe again, but the hurt stays.

Avery reconnects with Amira, who admits Charlie truly loved her. Soon Charlie asks to meet at Palace Pier and finally tells the truth: she has chronic kidney disease, is waiting for a transplant, and recently started dialysis.

She hid it because Avery was already drowning in grief, and Leyla was her support. Avery is shaken, triggered by how Halle kept parts of her illness secret, and says she can’t handle more secrecy.

She walks away.

Guilt drags Avery into a fog. Her friends and even Leyla show up for her.

Leyla confirms Charlie still loves Avery and invites her to a kidney-care meetup. Meanwhile Carmen helps Evan get therapy, and on a calmer call he shares the real story behind the “Yes” clue: he and Halle secretly eloped in Brighton, choosing love despite fear.

The story shifts something in Avery. Love, she realizes, isn’t safe, but it can still be right.

During finals and the reunion, Avery meets Charlie again at the pier. They can’t locate the last clue, but Avery apologizes for leaving, admits she loves her, and asks for another chance.

Fireworks bloom into a gold heart overhead, and they reconcile with a kiss. Avery finishes the year strong and decides to stay in Brighton another year, balancing pre-med with writing and rebuilding her bond with her dad.

Soon after, Charlie receives a kidney transplant in London. Avery waits with Esther and Leyla until the nurse confirms the surgery succeeded.

When Charlie wakes, she hands Avery a stapled script of their story titled “The Illusion of Us,” a promise that their real relationship—rules broken and all—has a future.

Characters

Avery Blackwell

Avery is the emotional and narrative center of Rules for Fake Girlfriends. She begins the story raw with grief after her mother Halle’s death, and that grief reshapes everything about her identity: her certainty, her plans, and even her sense of what she deserves.

For years she lived inside a rigid blueprint—Columbia, biology, med school, oncology—both as a way to honor her mother’s fight with cancer and to control a world that now feels terrifyingly unstable. The postcard scavenger hunt pulls her into a new kind of living, one that requires intuition, risk, and openness, and Avery’s arc is basically the slow loosening of her tight grip on “the plan.” Her strength shows up in persistence and loyalty—she keeps following clues even while doubting herself, and she keeps showing up for people she loves, like Colin in the hospital and her father despite their fractures.

But she also has sharp flaws born from pain: she can be reactive and suspicious when she senses secrecy, and she sometimes uses emotional distance as a weapon, especially in the fake-dating stage where she tries to engineer outcomes instead of trusting feelings.

Across the book she learns that love and ambition don’t have to be mutually exclusive, that grief isn’t a problem to solve but a landscape to walk through, and that her future can be chosen for herself—not only inherited from her mother’s suffering.

Charlie Evans

Charlie is a spark-plug character whose humor, speed, and warmth initially feel like the opposite of Avery’s heaviness, yet she’s carrying her own quiet devastation. Outwardly she’s charismatic, a little chaotic, socially fearless, and fluent in performance—qualities that make the fake-girlfriend setup believable and fun.

The train scene shows her instinct to improvise when cornered, but also how desperately she wants to be seen by someone who doesn’t yet know her heartbreak. Her lingering attachment to Leyla is real, but it isn’t the story’s endpoint; rather it reveals Charlie’s difficulty with endings and her hunger for reassurance that she’s lovable even after being left.

The deeper layer of Charlie is her chronic kidney disease, a secret that reframes her behavior throughout the middle of the novel. Her disappearances, evasions, and reliance on Leyla for support aren’t betrayals so much as survival strategies from someone who has lived too long inside medical uncertainty.

Charlie’s core conflict is between intimacy and protection: she loves hard and wants connection, but she fears becoming a source of pain, especially to Avery. Her growth is in learning that love requires truth even when truth is scary, and in trusting that she can be cared for without being pitied.

By the end, her reconciliation with Avery and her successful transplant don’t “fix” her, but they symbolize her choice to live openly rather than behind carefully managed illusions.

Halle Blackwell

Halle is physically absent but spiritually omnipresent, shaping the story through memory, objects, and the scavenger hunt that becomes Avery’s lifeline. In Avery’s recollections Halle is vibrant, playful, and artistic—her light paintings and elaborate clue-trails suggest a woman who experienced love as adventure and meaning as something you build out of ordinary places.

She’s also quietly strategic: even while battling cancer, she plans a years-old hunt so that her daughter can meet her younger self and find a path beyond grief. Halle’s character is defined by contradictions that feel human rather than idealized.

She is nurturing yet secretive, brave yet aware of her own limits, and deeply attached to family while still longing for Avery to step outside the family script. The postcard’s tone—loving, teasing, and gently challenging—shows Halle’s final act of motherhood as one of liberation.

Importantly, Halle is not only a saintly memory; the hunt reveals she was a young woman who fell in love impulsively, took risks, and changed course. That fuller portrait helps Avery stop turning her mother into a monument and instead see her as a model of lived complexity.

Evan Blackwell

Evan represents a different face of grief than Avery’s—one that collapses inward. After Halle dies, he drifts into depression and then into contamination rituals, and his removal of Halle’s photographs is both an attempt to survive and a kind of denial that terrifies Avery.

He doesn’t know how to talk about pain, so he tries to control the future instead, pushing Avery toward Columbia and a safe, linear success story. Under that rigidity is a man who loved Halle intensely and feels unmoored without her; the missing light paintings are not only erasure but also evidence that being surrounded by her art is unbearable.

Evan’s relationship with Avery is strained because they grieve differently and because he holds the parental power to approve or disapprove of her choices. Yet he’s not an antagonist.

His eventual openness—to therapy, to Carmen’s help, to telling Avery the story behind the “Yes” clue—reveals that his love is steady even when clumsy. The moment he shares their Brighton elopement and true anniversary is crucial: it shows Avery that love can be a leap, not a spreadsheet, and it lets Evan reclaim Halle’s memory as a shared story rather than a locked room.

Amira

Amira is Avery’s oldest anchor and an important mirror for what Avery becomes when secrecy and distance enter the friendship. She starts the book as protective, practical, and emotionally attuned to Avery’s grief, and her presence at the airport underscores that she is chosen family.

When Avery falls for Charlie and doesn’t tell Amira, Amira’s anger isn’t petty jealousy; it’s grief mixed with hurt that Avery no longer trusts her. Their rupture demonstrates how trauma can narrow a person’s world, making them cling to new intimacy even at the cost of old bonds.

Amira’s eventual reconciliation with Avery shows her maturity and generosity—she listens, forgives, and becomes the voice insisting that Avery acknowledge real love instead of spiraling in assumptions. She also functions as a stabilizing contrast to the Brighton whirlwind, reminding Avery that home relationships deserve honesty too.

By the end, Amira’s loyalty is intact but re-defined: she won’t be shut out, and Avery learns that love doesn’t have to be rationed between friend and partner.

Colin

Colin is the story’s quiet moral compass and emotional steadying force. Living with a disability and using a cane, he brings to the friend group a grounded resilience that never asks for spotlight.

He is observant—spotting the Heart Stone clue’s meaning and noticing Avery’s emotional missteps with Charlie—and he has a way of offering truth without cruelty. Colin’s warmth creates safe space, especially during Avery’s spirals, and his practical help with the scavenger hunt makes him a bridge between Avery’s grief mission and her everyday student life.

His injury late in the story, and Avery’s instinct to care for him, deepens their bond and reinforces the theme that love is also what you do when someone else is hurting. Colin’s romance with Maddi adds an extra layer to his character: he’s tender, sincere, and unafraid of public affection, modeling the kind of honesty Avery struggles to practice.

He’s not a “sidekick”; he’s a stabilizer who helps others see themselves clearly.

Maddi Newton

Maddi is a burst of color in every sense—Welsh, artistic, theatrical, and immediately at ease with messiness. As Avery’s roommate, she represents the possibility of a life that isn’t optimized for achievement, and her delight in Avery’s redecorating signals how Maddi values expression over order.

She’s also emotionally sharp; even when joking, she reads the room well, and her blunt declaration that Avery is in love with Charlie is a turning point because it forces Avery to confront feelings she’s been trying to choreograph. Maddi’s performance in Electra highlights her depth: she is someone who channels pain into art rather than hiding from it, and that capacity makes her a kind of guide for Avery’s creative-writing journey.

Her relationship with Colin shows her softer steadiness beneath the dramatic flair; she commits, supports, and celebrates without fear. Maddi’s role in the Cornwall trip also reveals her as a caretaker friend who knows distraction can be a form of survival, and she offers Avery solace without demanding quick healing.

Leyla

Leyla complicates the love triangle in a way that avoids caricature. She is not presented as a villainous ex but as someone charismatic and kind who still matters to Charlie.

Her friendliness toward Avery at the party, and her invitations to include both girls in gatherings, underline that she isn’t playing a cruel game; she’s living her life, perhaps unsure of her own feelings. Leyla’s presence pressures the fake-dating scheme to evolve into something real, because Avery watches Charlie around Leyla and feels emotions she wasn’t prepared for.

Later, Leyla becomes unexpectedly important as a support figure during Charlie’s illness and as someone who helps Avery understand the medical stakes. Her confession that Charlie still loves Avery, and her invitation to the Kidney Care meetup, show emotional maturity and genuine care.

Leyla represents a past that doesn’t need to be erased for a new love to be valid, and her role helps the story explore how people can remain meaningful even after romance ends.

Esther Evans

Esther is both a link to Halle’s past and a portrait of adulthood shaped by unfinished grief. As an administrator juggling the reunion and campus traditions, she appears stressed and strict at first, but her deeper significance is personal: she was Halle’s roommate, confidante, and partner in youthful adventures.

Through Esther, Avery gets a living, breathing sense of who her mother was before being “Mom,” and that re-humanizes Halle in a vital way. Esther’s role as Charlie’s mother adds a delicate tension—she is protective of her daughter while also honoring her bond with Halle, which makes her invested in Avery’s search.

Her suggestions about the time capsule tradition and her memories of Halle and Evan’s love story are not just exposition; they are acts of care, giving Avery a map through grief. Esther is a reminder that parents are also former students with messy histories, and that intergenerational echoes can bring healing rather than only comparison.

Cora

Cora walks the line between mystical atmosphere and grounded guardianship. She’s introduced as a tarot reader with theatrical flair, and the reading scene is crucial because it externalizes both girls’ inner conflicts in symbolic language.

Yet Cora’s real role is that of a keeper of promises: she has safeguarded Halle’s first time capsule for two decades, waiting patiently for Avery. Her shift from performance to sincerity reveals a character who understands when ritual helps and when truth must take over.

Cora is tied to themes of fate versus choice; she offers interpretations, not commands, and she reinforces that the hunt is about Avery finding her own direction, not merely discovering objects. By telling the girls they sit where their mothers once sat, she positions the story inside a cycle of love and loss, giving Avery both comfort and a sense of responsibility to continue living.

Carmen

Carmen is a secondary character with outsized emotional impact because she models healthy, boundary-based care. As Amira’s mother and a longtime family presence, she steps in where Evan cannot, offering Avery both practical help and the crucial reminder that a child cannot repair a parent’s grief alone.

Her willingness to support Evan into therapy shows her as proactive and compassionate, but her compassion doesn’t slide into enabling; she keeps Avery from drowning in guilt. Carmen functions as the mature voice in the novel’s web of relationships, reinforcing that love is not only passion and sacrifice but also knowing what is not yours to carry.

Circe

Circe, Avery’s cat, is more than a cute detail; she’s a small symbol of home, continuity, and grounding. In the opening, Circe sprawled across luggage captures Avery’s reluctance to leave familiar grief behind, and later Circe’s presence in the flat helps make Brighton a livable space rather than a temporary quest site.

Circe also quietly emphasizes Avery’s caretaking instincts: even while unraveling emotionally, Avery maintains responsibility for another life, which mirrors how she keeps showing up for human relationships too.

Rowan

Rowan appears mainly as part of the friend group that shelters Avery after heartbreak, and their importance lies in what they represent: community that gathers without needing an invitation. Rowan isn’t deeply individualized in the summary, but their role in the Cornwall trip and group support underscores a theme that healing is collective.

They help normalize Avery’s pain by keeping her in the flow of living—meals, beaches, jokes—making them part of the novel’s argument that friendship can be a life raft when romance or family falters.

Themes

Grief as a living process rather than a problem to solve

Avery’s life in Rules for Fake Girlfriends is shaped by the fact that grief doesn’t arrive as a single emotion or a clean timeline. It shows up as denial when she questions whether leaving New York is a mistake, as anger when she sees her father erasing Halle’s photographs, and as guilt when she worries that stepping off the Columbia track is a betrayal of her mother’s sacrifice.

The story treats grief as something that keeps changing its form depending on where Avery is and who she is with. In New York, her mourning is tight and airless: a summer apartment, missing art, a father retreating into depression and later contamination rituals, and a silence that makes Avery feel alone in a house full of memory.

Brighton gives her a different context for the same pain. Instead of being trapped in loss, she is pushed into motion by Halle’s scavenger hunt.

Each clue becomes a way to feel Halle’s presence without pretending Halle is still alive, and that balance matters. The hunt lets Avery cry, laugh, doubt herself, and still keep going, which mirrors the way real mourning works.

It isn’t “move on” versus “stay stuck. ” It’s learning to carry the person differently.

Grief also affects how Avery loves. When she first meets Charlie, the ease of talking to a near stranger is a relief because it temporarily loosens the grip of tragedy.

Later, when Charlie hides her illness, Avery’s reaction is not only about romantic trust but about being triggered by the pattern of sickness and secrecy she lived through with Halle. The book shows that grief can make people protective and reactive, sometimes unfairly, because every new threat feels like a repeat of the first loss.

Yet the story doesn’t punish Avery for this. It lets her fall apart, withdraw from classes, lean on her friends, and then return.

Healing, here, is not a sudden breakthrough. It is Avery accepting help from Amira, Colin, Maddi, Rowan, and even Leyla, and it is her father re-entering life through therapy.

By the end, grief hasn’t disappeared. Halle is still gone.

But Avery has learned that love, work, and joy are possible without needing to “fix” the ache first. The change is that she stops treating grief as evidence that she must freeze her life, and starts seeing it as something she can live with while still choosing a future.

Selfhood and the courage to choose an unfinished path

Avery begins the story with an identity that has been mapped out in detail: perfect grades, pre-med, oncology, and Columbia as proof she is doing the “right” thing with her life and her mother’s legacy. What changes is not that she suddenly rejects science or ambition, but that she learns ambition can be shaped by more than fear or duty.

The postcard from Halle is powerful because it doesn’t give Avery instructions like a parent who wants control. It gives her permission to step into uncertainty.

That invitation forces Avery to make a choice without guarantees, and the book keeps returning to the idea that becoming yourself often means acting before you feel ready. Her move to Brighton is not presented as a magical escape; she doubts herself constantly, especially when clues are confusing or lost.

But those doubts are part of the theme. Avery’s sense of self is being built in real time, with grief and curiosity pulling in different directions.

Brighton also gives Avery a place to test who she is outside the expectations of home. Her friendship with Maddi and Colin, her creative-writing class, her new space filled with thrifted color, and her willingness to follow a scavenger hunt into marketplaces and beaches all show a version of Avery that could never have existed if she stayed on a rigid track.

Importantly, the book doesn’t frame creativity as the opposite of science. Avery adds writing to her schedule not as rebellion but as expansion, a way to honor Halle while still moving toward medicine.

The story suggests a meaningful life can hold multiple callings at once, and that the pressure to pick one “acceptable” version of yourself can shrink a person.

Her romantic growth fits into this same arc. Avery has never dated, never been to real parties, and has always kept her control through planning.

The fake-dating arrangement forces her into social spaces where she can’t rehearse everything. She learns to improvise, to risk embarrassment, and to listen to her own feelings instead of treating them like distractions.

Even when she makes mistakes—like pushing Charlie away to serve a plan—those mistakes are part of learning who she is. By the end, Avery’s biggest act of selfhood is not choosing Charlie, or choosing medicine, or choosing writing.

It is choosing Brighton again with clear eyes. She decides to stay because she wants to, not because grief is pushing her or because her mother designed the path.

The theme lands in the idea that identity is not a destination you reach by collecting achievements. It is something you practice through repeated, imperfect choices.

Love that starts as performance and becomes truth

The fake-girlfriend setup could have stayed a simple romantic gimmick, but the book uses it to explore how people perform roles before they understand what they truly want. When Charlie grabs Avery’s hand on the train, both girls are using performance as a shield.

Charlie wants to protect herself from the ache of Leyla’s breakup, and Avery wants a moment where she isn’t “the girl whose mother died. ” The performance gives them relief, but it also makes space for genuine care to grow.

Their early pretending is full of small tenderness—talking easily, sharing personal objects, laughing over inside jokes—and those details show that emotional intimacy doesn’t always begin with grand declarations. Sometimes it begins with a role you take on for safety, then realize feels like home.

The story also traces how performing love can warp it. Avery’s decision to keep the fake relationship going to make Leyla jealous turns affection into strategy.

She starts pulling away from Charlie in public, not because she doesn’t care, but because she wants to force a specific outcome. The consequence is not just that Charlie feels hurt; Avery learns that treating love as a tool makes everyone less human.

This is why Maddi’s blunt observation that Avery is in love hits so hard. Avery has been acting like the relationship is artificial, but her body and heart are already telling a different story.

The London date and the onstage kiss crystallize the theme: when the rules of pretending collapse, what remains is feeling that is already real. The kiss works not because it is dramatic, but because it reveals truth that had been waiting behind the performance.

After they become official, the story stays honest about how love doesn’t erase insecurity. Avery still fears loss, Charlie still fears being seen as fragile, and both struggle with trust.

Yet the shift from performance to honesty becomes a kind of emotional adulthood. Avery learns that real love cannot be controlled like a plot; it has to be met directly.

Charlie learns that affection doesn’t require hiding the parts of herself that are scared. Their reconciliation later is built not on an idealized romance, but on Avery’s willingness to say, clearly, that she loves Charlie and is choosing her with full knowledge of the risks.

The title of Charlie’s script, “The Illusion of Us,” underlines the theme: what began as illusion still mattered, because it led them to something true. The book suggests that love can start in odd places, even in games, but becomes meaningful when both people stop using it to manage fear and start using it to meet each other as they are.

Honesty, secrecy, and the cost of trying to protect someone

Secrecy runs through the story in two parallel lines: Evan hiding his spiraling grief and removal of Halle’s art, and Charlie hiding her chronic kidney disease. Both kinds of secrecy come from a desire to protect someone else, but the book is clear that protection through silence often creates a different kind of harm.

Evan avoids talking about the photographs because he can’t bear the pain of her absence. In calling Halle’s work “old junk,” he is not dismissing her so much as trying to survive his own loss.

Still, that survival strategy isolates Avery and makes her feel that her mourning is unwelcome at home. The book shows how secrecy inside a family can turn grief into loneliness, even when love is still present.

Charlie’s secrecy is more complicated because it exists inside romance that is still new. She hides her illness because she senses Avery’s grief is raw and doesn’t want to add another layer of fear.

She leans on Leyla because she needs support and because Leyla already knows the medical reality. From Charlie’s perspective, silence is care.

From Avery’s perspective, silence is the same betrayal she felt when Halle shielded her from the seriousness of cancer. That collision matters thematically: honesty is not simply a moral rule here; it is tied to trauma.

Avery is not angry only because Charlie kept a secret, but because secrets about sickness have already rewritten her life once. The story respects that reaction while also letting Avery grow past it.

What makes this theme land is that the resolution doesn’t say “never keep anything to yourself. ” Instead it asks what honesty is for.

Is honesty meant to unload without thought, or to invite someone into your real life? Charlie learns that allowing Avery to know the truth is not cruelty; it is trust.

Avery learns that being told the truth does not mean she must fix it or control it. She can be present without being the savior.

Leyla’s role supports this theme too. Even though she is the ex, she acts as a bridge rather than a rival, making it clear that care can exist outside romantic ownership.

By the end, honesty becomes the ground on which love and family can stand without collapsing under fear. Evan begins therapy and shares the real story of his elopement with Halle.

Avery shares her story and accepts that she can’t manage everyone’s pain on her own. Charlie shares her medical reality openly before the transplant.

The book argues that secrecy may feel like kindness in the moment, but it keeps people from carrying hardship together, which is the only way they can survive it in the long run.

Legacy, memory, and the way art keeps people present

Halle’s scavenger hunt is more than a plot engine; it is the story’s way of exploring how a person can remain part of the world after death without being reduced to nostalgia. Halle’s light paintings and time capsules are acts of communication across time.

They let Avery experience her mother not only as someone who died, but as someone who once loved music festivals, made impulsive choices, argued with friends, and fell in love in risky, joyful ways. This matters because grief can flatten the dead into saints or shadows.

The hunt fights that flattening. Each clue is a reminder that Halle was a full person, and by learning that, Avery gains permission to be a full person too.

Art, in this theme, is not decoration. It is a language.

Halle used light painting to leave messages that can’t be spoken directly, like “Manifest” or “CORA. ” She used time capsules to tie locations to emotion, so that Brighton itself becomes a living archive.

Avery opening each capsule is like opening a door into a memory that still has heat inside it. The memory is not frozen in a frame.

It changes Avery in the present. Even the broken floppy disk fits this theme: not every piece of legacy survives perfectly, but the attempt still matters.

When Avery believes the hunt is over, her devastation shows how strongly she needed this connection. Charlie’s comfort in that moment becomes another form of legacy-building, because it creates a new memory attached to the same places Halle once loved.

The theme also explores legacy through intergenerational echoes. Avery and Charlie sitting in Cora’s back room where their mothers once sat, Esther and Halle having been roommates, and the reunion bringing the past into contact with the present all suggest that lives are linked in webs of choice and chance.

Avery doesn’t just inherit biology or career pressure. She inherits stories, places, music, and a model of love that is brave enough to risk pain.

Evan’s confession that Halle said “Yes” at the flea market reframes Avery’s understanding of her parents’ relationship. It teaches her that the love she is building with Charlie is not separate from her mother’s story; it is a continuation shaped by new circumstances.

By ending with Charlie’s recovered script and successful transplant, the book shows legacy moving forward rather than backward. Halle’s art gives Avery roots, but Avery’s decisions grow into new branches.

Memory becomes a guide, not a cage.