Tell Me Everything Summary, Characters and Themes | Elizabeth Strout

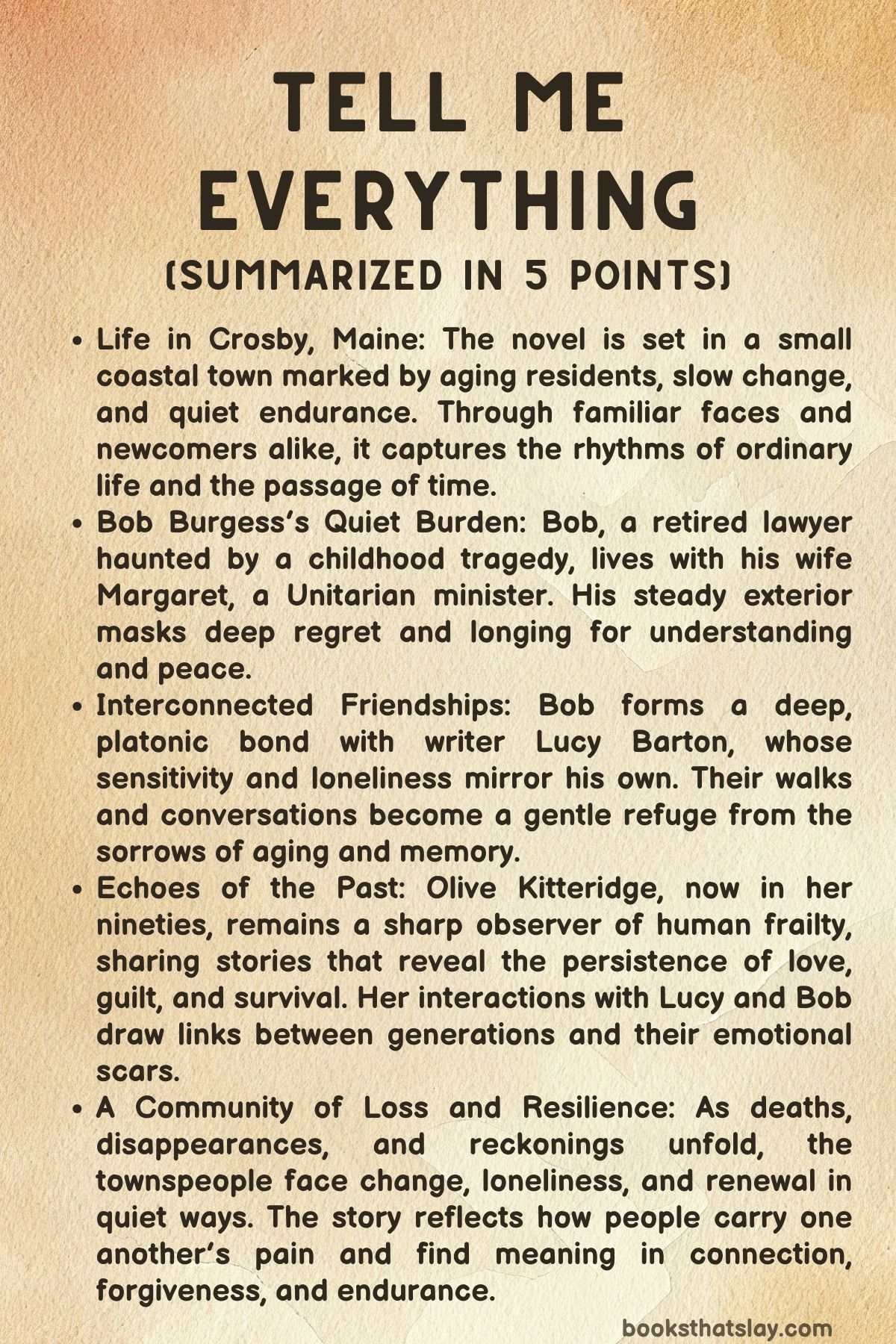

In Tell Me Everything, Elizabeth Strout returns to the familiar fictional landscape of Crosby, Maine, to explore aging, memory, guilt, and the quiet endurance of human relationships. At its center stands Bob Burgess, a retired lawyer haunted by a childhood tragedy and sustained by small acts of kindness and connection.

Strout gathers familiar figures from her earlier works—Olive Kitteridge and Lucy Barton—each confronting solitude, regret, and the search for meaning in later life. Through their intersecting lives, the novel reflects on the nature of friendship, the burden of love, and the fragile, luminous humanity found in ordinary days.

Summary

The novel unfolds in the quiet town of Crosby, Maine, where the rhythms of the seasons mirror the passing of time for its aging residents. Bob Burgess, sixty-five, lives with his wife, Margaret Estaver, a Unitarian minister admired for her composure and moral steadiness.

Bob’s past is marked by a tragedy that shadows him still—he accidentally caused his father’s death as a boy by playing with a car’s gearshift. Though outwardly calm, Bob carries a lifelong sorrow beneath his gentle manner.

Crosby’s long-time observer, Olive Kitteridge, now ninety, still resides at the Maple Tree Apartments, gruff yet perceptive as ever. She disapproves of most ministers, but sees depth and sadness in Bob, recognizing his quiet decency.

Olive, having endured the isolation of the pandemic and the loss of her friend Isabelle to a nursing home, remains sharply aware of her own mortality and loneliness.

Nearby lives Lucy Barton, a novelist who fled New York with her ex-husband, William, during the pandemic. Locals regard her warily as one of the outsiders driving up property prices.

She keeps to herself, except for her walks with Bob, who has become her closest friend. Their companionship is built on mutual understanding—he smokes secretly, she listens with empathy, and both share unspoken griefs from their pasts.

Their friendship becomes a sanctuary, a quiet meeting of souls searching for comfort.

When Olive asks to meet Lucy, believing she might use one of her stories in a novel, Bob arranges it. Their encounter begins awkwardly but soon turns intimate as Olive recounts her mother Sara’s lost love and the enduring sorrow that followed.

Lucy listens and interprets Olive’s story as one of love and haunting—a reflection of lives shaped by loss and secrecy. Speaking her truth gives Olive relief, a release from decades of resentment toward her mother.

Meanwhile, the town’s stillness is disturbed by the disappearance of Gloria Beach, an elderly woman known for her harshness. Her son, Matthew, becomes the prime suspect.

Gossip spreads, and old memories resurface. Bob’s sister, Susan, recalls the Beach family from childhood, and Olive mutters they were “crazy, crazy, crazy.

” The case remains unresolved, deepening the novel’s undercurrent of mystery and melancholy.

Winter brings introspection and weariness. Bob volunteers at food pantries and shelters, small gestures that help him cope with loneliness.

His brother Jim, a successful New York lawyer, stays distant. Margaret devotes herself to her church work.

During Christmas, Bob remembers wounding his mother as a child with careless words—a memory that returns each holiday. At Margaret’s Christmas Eve service, Lucy attends with William; despite the warmth of the evening, both women feel hidden sadness.

Margaret recognizes in Lucy’s tears the same yearning she feels—the need for connection that persists beneath even a faithful life.

Charlene Bibber, a widowed house cleaner, becomes another thread in Crosby’s fabric. She befriends Lucy after volunteering together at a food pantry.

Their walks by the river offer Charlene rare companionship, though she remains burdened by loneliness and financial hardship. Her story reveals the quiet suffering of working-class women in a changing town, where outsiders buy up homes and lifelong residents struggle to stay.

Lucy, meanwhile, confides to Bob her despondency—her daughters’ distance, her sense of being unneeded, and her sadness over a houseplant she believes she has harmed. Bob listens tenderly.

They discuss fear, aging, and the turmoil of the world beyond their small town. In their shared vulnerability, they find solace.

Then, an unexpected call from Bob’s first wife, Pam, upends his routine. Pam, now wealthy but miserable in East Hampton, confesses she became an alcoholic during the pandemic, driven by boredom and betrayal after discovering her husband’s affair.

Having fought her way to sobriety, she visits Bob in Maine. Their meeting is bittersweet—two people aged and changed by life, sharing compassion but not rekindled romance.

Pam’s vanity and old habits remain, yet Bob’s empathy for her suffering is unwavering.

After Pam’s departure, Bob learns from her that Jim’s wife, Helen, is dying of pancreatic cancer—a secret Jim kept from him. The news devastates Bob.

When Helen later calls to say goodbye, thanking him for his lifelong kindness, her words echo through his grief. Her death leaves him hollow, even as he continues his quiet routines and care for others, including Mrs.

Hasselbeck, a lonely, elderly woman whose need for dignity breaks his heart.

Olive resurfaces, telling Lucy a story about Janice Tucker, a hairdresser who cared for a young, abused man. Lucy calls Janice a “sin-eater,” someone who absorbs others’ pain.

Later, she tells Bob that he too is one—a man who takes others’ burdens as his own. Bob accepts this quietly, recognizing it as truth.

Spring brings both renewal and loss. Gloria Beach’s decomposed body is found in a quarry, her life of cruelty and suffering revealed through her journal.

Bob becomes involved as her son Matthew’s lawyer, trying to piece together a life marked by pain and misunderstanding.

Helen’s funeral reunites the Burgess family. Bob comforts his grieving brother Jim, who confides that he wants his ashes scattered over the Androscoggin River.

Pam attends, now stronger in her recovery, sharing her own journey of forgiveness and acceptance, including her son’s transition and her reconciliation with herself. Life, the novel suggests, continues in small redemptions.

As spring ripens, Bob and Margaret’s marriage falters. A sermon trip to Boston triggers a fierce argument—Bob feels abandoned; Margaret accuses him of projection.

Their reconciliation is fragile, leaving them both uncertain. Bob immerses himself in defending Matt Beach, forming a cautious friendship with the troubled man.

He insists Matt stay connected, worried for his safety.

Bob’s feelings for Lucy deepen until he realizes he loves her. Their emotional intimacy grows, but Lucy, too self-aware, understands this love will never be acted upon.

When Bob spies on her in a grocery store, watching her contradict herself with different people, he is reminded of her remark that “no one truly knows anyone. ” Their friendship cools but survives.

Pam relapses after a painful visit from her ex-husband’s lover, but with Bob’s support, she steadies herself again. Jim visits Maine, subdued by grief.

Bob and his siblings talk of the past and of who caused their father’s fatal accident. The truth remains uncertain, each memory clouded by trauma.

Margaret’s work stabilizes after a scandal in her church, and life seems to level out. Lucy and William remarry, a decision that both surprises and saddens Bob.

At the celebration, Margaret officiates; Bob congratulates Lucy, their silent glance acknowledging love and loss at once. Later, Olive remarks to Bob that his devotion to Margaret—not his yearning for Lucy—is what defines him.

The final chapters bring acceptance. Bob resumes his life in Crosby with calm endurance.

Margaret hangs a portrait of him painted by Matt Beach, a symbol of quiet recognition. Lucy and Bob continue their walks, their affection tempered into friendship.

When Bob sees Matt walking hand in hand with a woman, he feels a rare joy, believing healing is possible. Olive, now ninety-one, listens as Lucy recounts her unconsummated love for Bob—an affection that steadied her and, in its restraint, preserved them both.

In the end, Tell Me Everything is a meditation on aging, forgiveness, and the enduring need to bear witness to one another’s lives. Love, the book insists, may not rescue or fulfill, but it sustains—the small, luminous force that keeps ordinary people moving through the quiet seasons of their days.

Characters

Bob Burgess

Bob Burgess stands at the emotional center of Tell Me Everything, a man defined by remorse, decency, and quiet endurance. A retired lawyer living in Crosby, Maine, Bob carries within him the heavy residue of a childhood tragedy—his belief that he accidentally caused his father’s death.

This memory has shaped his adult life, infusing his actions with an undercurrent of guilt and tenderness. Though he presents a façade of calm respectability, his life is marked by private fears, sleepless introspection, and a deep-seated anxiety about being unloved or forgotten.

His relationship with Margaret, while stable, lacks warmth; she is practical and self-assured, while he is introspective and self-doubting.

Bob’s emotional life is enriched yet complicated by his friendship with Lucy Barton. In Lucy, he finds understanding without judgment, and together they share an unspoken melancholy that defines their companionship.

He is drawn to Lucy’s empathy and intelligence, and though their connection borders on romantic longing, it remains rooted in emotional rather than physical intimacy. Bob’s compassion extends beyond Lucy—to the lonely, the broken, and the marginalized of Crosby.

His visits to the elderly Mrs. Hasselbeck and his concern for the troubled Matt Beach reveal a man who seeks redemption through kindness.

Yet his goodness often stems from a desire to atone for past guilt rather than pure altruism. In the novel’s closing chapters, Bob comes to accept the unresolved nature of his past and the limitations of human understanding, finding peace in small acts of love and constancy.

Lucy Barton

Lucy Barton, the quiet novelist from New York, embodies emotional intelligence, fragility, and resilience. Having escaped a childhood of deep poverty and shame, Lucy carries with her a lifelong sensitivity to suffering.

In Crosby, she becomes both observer and participant—an outsider who nonetheless connects intimately with others like Bob Burgess and Charlene Bibber. Her introspective nature allows her to absorb others’ pain, acting as what Olive Kitteridge calls a “sin-eater.

” Lucy’s empathy is profound but also isolating; she listens deeply but rarely reveals her own loneliness, except in moments of rare vulnerability.

Her friendship with Bob is one of mutual solace—a communion of two souls weary from guilt and longing. Their walks by the river symbolize emotional refuge and fleeting peace, yet Lucy’s sadness runs deep, tied to her feelings of estrangement from her daughters and her uncertain sense of belonging.

When she reunites with her ex-husband William, the decision to remarry him suggests a search for stability rather than passion, a return to what feels familiar and safe. Lucy’s reflections on life’s meaning—her questions about love, suffering, and existence—frame much of the novel’s philosophical undercurrent.

By the end, her understanding of love matures into something humble and profound: love as endurance, as kindness, as the act of not abandoning another even when affection has faded into habit.

Margaret Estaver

Margaret Estaver, Bob’s wife, is a Unitarian minister whose life is structured by purpose and conviction. She is intelligent, disciplined, and confident in public, yet her private world is marked by emotional distance and control.

To others in Crosby, she represents stability, but within her marriage, her moral certainty often borders on self-righteousness. Margaret’s inability to fully grasp Bob’s internal anguish creates a quiet tension between them; she intellectualizes pain rather than feeling it, which makes her both admirable and exasperating.

Margaret’s self-image as a caretaker and moral guide is challenged when she and Bob quarrel about emotional neglect. Her apology after looking up “gaslighting” marks a rare moment of humility and growth.

Over time, she emerges as the steady anchor of Bob’s life—not because she understands him perfectly, but because she remains beside him through the ordinary and the painful alike. Her presence in the story reaffirms Strout’s theme that constancy, not passion, sustains love in the long run.

Olive Kitteridge

Olive Kitteridge, the acerbic yet deeply human observer of Crosby life, serves as a bridge between the past and the present. Now ninety-one, she is sharp-tongued, unsparing, and possessed of a moral clarity that borders on cruelty.

Yet beneath her brusque exterior lies an immense capacity for compassion and reflection. Her interactions with Lucy Barton and Bob Burgess highlight her continuing curiosity about others’ lives and her yearning to be known.

Through Olive, Tell Me Everything revisits Strout’s enduring preoccupations—aging, regret, and the stubborn persistence of love. Olive’s memories of her mother’s thwarted romance and her father’s despair illustrate how personal histories shape identity and bitterness.

Her friendship with Isabelle near the novel’s end softens her edges, showing that even in old age, the human heart can still ache for connection. Olive’s candid insight to Bob—that his feelings for Lucy were a “crush, not a ghost”—provides one of the book’s most grounded moments of truth.

Pam Burgess

Pam Burgess, Bob’s ex-wife, offers a poignant portrait of midlife collapse and redemption. Once elegant and socially successful, Pam spirals into alcoholism and loneliness after discovering her husband’s infidelity.

Her confessions to Bob reveal a woman humbled by her own weakness and searching for dignity. Pam’s struggles with addiction and her attempt to make amends through Alcoholics Anonymous are marked by self-awareness and lingering vanity; she is both tragic and human, capable of self-pity and genuine remorse.

Pam’s relationship with Bob rekindles old tenderness but also underscores the gulf between who they were and who they have become. Her relapse after Lydia’s visit demonstrates the fragile nature of recovery, while her acceptance of her son’s gender transition reflects a newfound capacity for love untainted by judgment.

Through Pam, the novel explores shame, self-deception, and the quiet heroism of beginning again.

Jim Burgess

Jim Burgess, Bob’s older brother, embodies the burdens of pride and repressed guilt. Outwardly successful as a New York lawyer, Jim remains emotionally closed and controlling, haunted by his own belief that he caused their father’s death.

His secrecy about his wife Helen’s terminal illness and his volatile relationship with his son reveal his inability to process grief. Jim’s arc mirrors Bob’s but in a darker key—where Bob seeks forgiveness, Jim clings to denial.

After Helen’s death, Jim’s isolation deepens, and his rare moments of vulnerability with Bob hint at the depth of his pain. By the novel’s conclusion, he becomes a tragic figure of self-containment—broken not by evil but by emotional paralysis.

His story underscores the novel’s larger theme that guilt, left unspoken, corrodes the soul.

Charlene Bibber

Charlene Bibber represents the working-class resilience and loneliness of small-town life. A widow who cleans houses to survive, she is defined by her weary pragmatism and longing for dignity.

Her friendship with Lucy Barton provides her with warmth and companionship, yet she remains self-conscious about her social status. Charlene’s reflections on class, kindness, and exploitation lend the novel its social realism.

Through Charlene, the narrative gives voice to those whom society overlooks—the cleaners, caretakers, and aging poor of towns like Crosby. Her gradual drift away from Lucy as life changes reflects the transience of human bonds, even those formed through shared pain.

Matt Beach

Matt Beach’s tragic story binds the novel’s themes of inheritance, guilt, and compassion. The suspected murderer of his mother, Gloria Beach, Matt is portrayed not as a villain but as a wounded soul trapped in a cycle of trauma.

His diaries, filled with conflicting emotions of love and hatred toward his mother, reveal the psychological scars of abuse and neglect.

Bob’s decision to defend Matt becomes an act of grace and self-redemption, as he recognizes in the young man a reflection of his own brokenness. Under Bob’s guidance, Matt begins therapy and tentatively rebuilds his life.

His painting of Bob serves as both literal portrait and symbolic mirror—a depiction of endurance in the face of sorrow.

Helen Burgess

Helen, Jim’s wife, appears briefly but profoundly. Dying of pancreatic cancer, she reaches out to Bob with gratitude and love, asking him to care for Jim and their son.

Her serenity contrasts sharply with the anguish around her, making her death a quiet moral pivot for the novel. Helen represents grace amid suffering—the acceptance that life’s beauty lies in its impermanence.

Themes

Guilt and the Weight of the Past

In Tell Me Everything, guilt emerges as an invisible companion shaping nearly every character’s emotional landscape, most notably Bob Burgess. His childhood memory of possibly causing his father’s death becomes a psychological wound that defines his entire adult life.

The uncertainty surrounding the accident—whether he or his brother Jim was truly responsible—does not ease the pain but rather amplifies it, as ambiguity itself becomes a form of punishment. Bob’s guilt manifests not only as regret but as a pervasive caution in his relationships and decisions.

His kindness, patience, and tendency to absorb others’ burdens all stem from an internal need to atone for a crime that may not even be his. Strout portrays guilt not as a discrete emotion but as a lifelong state of being, a force that can twist affection into obligation and empathy into quiet suffering.

For Olive Kitteridge and Pam, guilt also lingers in the form of failed love and self-destruction—Olive’s estrangement from her family, Pam’s alcoholism, and their respective self-judgments reinforce the novel’s suggestion that remorse can be both corrosive and redemptive. By showing how these characters carry their shame through decades, the narrative transforms guilt from a singular event into an enduring condition, suggesting that living with the past—without fully resolving it—is the human experience itself.

Loneliness and the Search for Connection

The quiet rhythm of Crosby, Maine, provides a backdrop for the persistent ache of loneliness that seeps through Tell Me Everything. The novel’s characters, whether aging or middle-aged, live surrounded by others yet remain profoundly alone.

Bob and Lucy Barton’s friendship arises from this shared solitude—a relationship sustained less by words than by the relief of being seen. Their walks by the river, marked by small confessions and silences, reveal that companionship in later life is not about passion but about the recognition of another’s inner ache.

Olive’s story adds another layer, depicting old age as a confrontation with isolation that no amount of sharp wit or stubborn pride can ward off. Strout examines how loneliness becomes both a symptom and a truth of human existence: even love, marriage, and friendship cannot fully erase the feeling of separateness.

Margaret’s role as a minister—professionally surrounded by people yet spiritually detached—illustrates how even those who serve others may live with quiet emotional deprivation. The novel suggests that connection, though fleeting, is sacred precisely because it is fragile.

In the world of Crosby, loneliness is not an anomaly but a shared condition, and moments of tenderness—a walk, a conversation, a simple gesture—become acts of resistance against the silence that defines their lives.

Aging and Mortality

Aging in Tell Me Everything is portrayed with unflinching honesty, neither sentimentalized nor dramatized. The town’s slow seasons mirror the decline of its residents—bodies weaken, memories blur, and daily rituals acquire a fragile grace.

Strout captures how growing old strips away pretense, forcing her characters to confront what remains of their lives when ambition and desire fade. Bob’s awareness of mortality is both physical and existential; every act, from smoking in secret to visiting an elderly client, carries a muted recognition of time running out.

Olive’s ninety-one-year-old perspective reveals the loneliness of outliving one’s peers and the terror of irrelevance, while Pam’s struggles with addiction in later life show how aging does not necessarily bring wisdom but sometimes a desperate reckoning with one’s failures. Death in this novel is not an endpoint but a quiet presence woven into daily existence—a call that humbles and clarifies.

Helen’s illness, the death of townspeople, and even the discovery of Gloria Beach’s body underscore the fragility of life and the randomness of survival. Yet, rather than despair, Strout offers acceptance: the grace lies not in defying mortality but in finding meaning within its inevitability.

The Fragility of Marriage and Human Relationships

Marriage in Tell Me Everything is portrayed as both a shelter and a site of quiet despair. Bob and Margaret’s union, viewed by outsiders as stable, is undercut by emotional distance and unspoken resentment.

Their arguments, especially the confrontation after Margaret’s trip to Boston, reveal the delicate balance between love and irritation that long-term relationships demand. Strout captures the complexity of commitment—how affection can coexist with frustration, and forgiveness can become habit rather than choice.

Through Pam’s failed marriage and subsequent recovery, the novel also examines the illusion of happiness in relationships built on appearance rather than truth. Even Lucy and William’s remarriage, which outwardly restores a sense of order, carries an undertone of resignation rather than passion.

The novel insists that all relationships, romantic or otherwise, depend on endurance and grace rather than certainty. Strout suggests that love, in its truest form, survives not through perfection but through persistence—through the small, daily choices to stay, listen, and forgive.

Ultimately, the fragility of human connection is what makes it precious; every reconciliation in the story feels hard-won because it resists the ease of sentimentality.

Redemption through Compassion and Understanding

Compassion functions as the moral core of Tell Me Everything, offering redemption to characters burdened by guilt, fear, and disappointment. Bob’s kindness toward others—the elderly woman with cats, his troubled client Matt Beach, his ex-wife Pam—reveals an instinct to heal not through grand gestures but through patient presence.

Strout uses these quiet acts of empathy to suggest that redemption is not achieved through confession or religious absolution but through human connection. Lucy’s gentle listening, Olive’s late-life honesty, and even Pam’s participation in Alcoholics Anonymous embody different forms of seeking forgiveness—of oneself and others.

Compassion becomes a way to make sense of life’s randomness, a means to bridge the vast emotional distances between people. Importantly, the novel resists idealizing goodness; it acknowledges that empathy often coexists with exhaustion, confusion, and self-doubt.

Yet, by the book’s end, small mercies—an offered hand, a shared walk, a word of comfort—accumulate into something resembling grace. Redemption, Strout suggests, does not erase the pain of the past but transforms it into a capacity for tenderness, allowing her characters to keep living with dignity and hope despite everything they have lost.