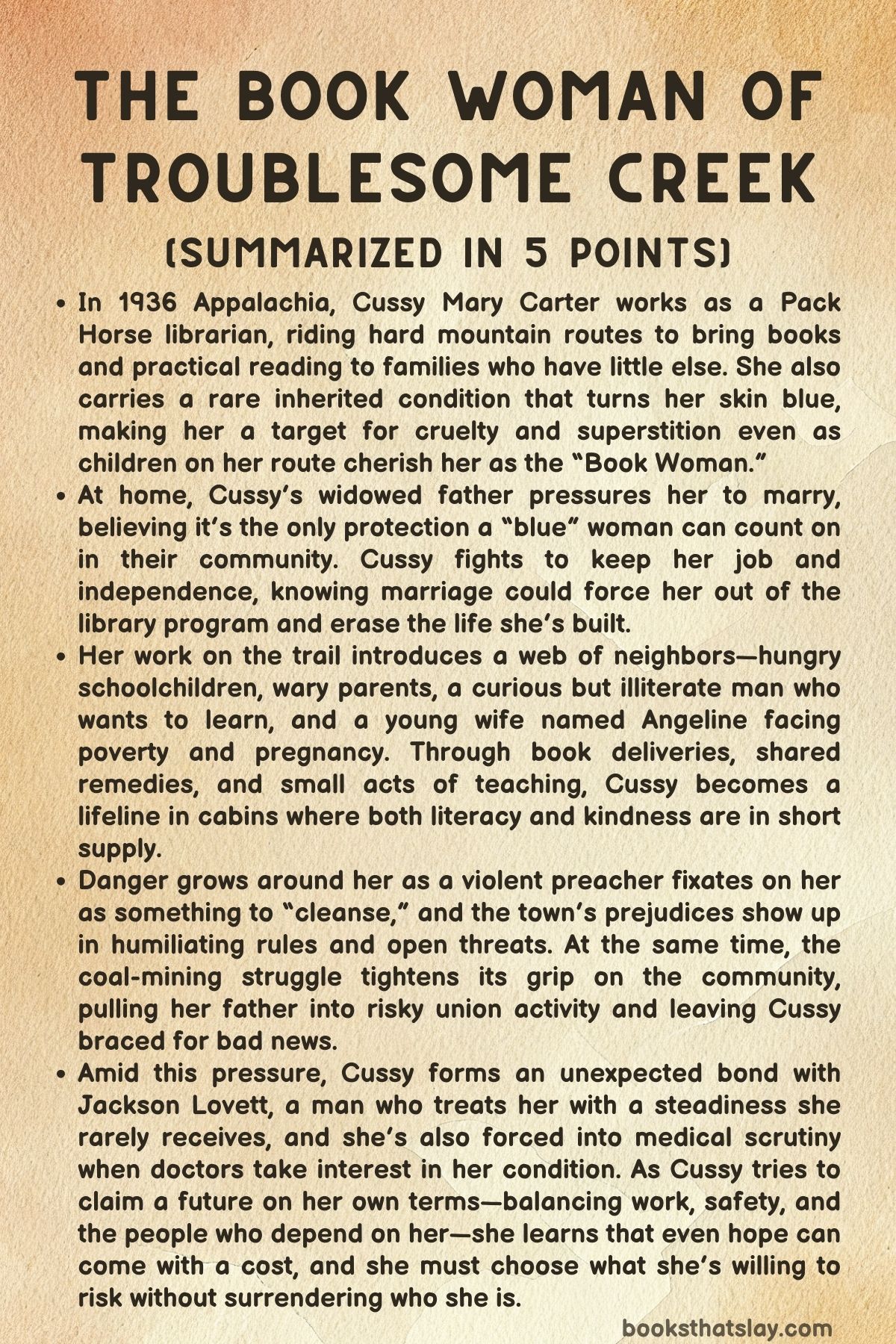

The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek Summary, Characters and Themes

The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michele Richardson is a historical novel set in Appalachia during the Great Depression, following Cussy Mary Carter, a young Pack Horse librarian who delivers books and practical reading material to isolated families in the Kentucky mountains. Cussy is also one of the local “Blue People,” born with a rare condition that turns her skin blue and makes her a target for cruelty, superstition, and exploitation.

As she rides her route, she becomes a lifeline to her patrons—while fighting for safety, dignity, and the right to shape her own future.

Summary

In 1936 Kentucky, nineteen-year-old Cussy Mary Carter works as a Pack Horse librarian, riding through rugged mountain trails to deliver books, magazines, and pamphlets to families cut off by poverty and distance. The work gives her pride and purpose, but it also puts her in danger—especially because Cussy’s skin is visibly blue, a hereditary condition that marks her as one of the “Blue People” and draws fear, insults, and gossip.

At home in Troublesome Creek, her father, Elijah, worries constantly about her safety and believes marriage is the only way to protect her. Cussy resists, knowing that if she marries a man considered employable, WPA rules could cost her the job she loves.

Elijah begins calling in suitors under the old custom of the “courting candle,” which limits how long a man may stay. One by one, the men arrive, glance at Cussy’s blue hands and face, and recoil.

A land-hungry suitor named Hewitt Hartman comes mainly to inspect the deed Elijah offers as a dowry; once he sees Cussy up close, he ends the visit himself and refuses her. Still, Elijah continues pushing, convinced time is running out for his daughter.

Eventually he agrees to a match that horrifies Cussy: Charlie Frazier, an older widower tied to the notorious preacher Vester Frazier, a man known for violent “cleansings” and public humiliation of anyone deemed sinful or different.

Cussy pleads with her father not to force the marriage, but Elijah insists, believing he is securing her future. The wedding becomes a nightmare.

Charlie assaults and beats her, hiding her face so he does not have to look at her color. Cussy wakes injured and terrified, with her father and a doctor trying to tend to her.

Charlie dies during the aftermath, and Elijah buries him quickly, along with the courting candle, as if trying to bury the whole bargain. Cussy survives, heals slowly, and returns to the only life that still feels like her own: the book route.

With Charlie’s death, Cussy inherits his mule, Junia, a battered animal she nurses back to strength with care and what little money she can spare. Junia proves loyal and protective—gentle with women and children, wary and aggressive toward men.

When Cussy rides again, her patrons greet her as the Book Woman, and she delivers not only stories but also practical knowledge: patterns, recipes, remedies, and scraps of news. She keeps a shared scrapbook of useful clippings that mountain families can pass from hand to hand.

On her route, Cussy visits Angeline Moffit, a teenage wife doing her best to hold a struggling household together. Angeline’s husband, Willie, lies in bed with a severe foot wound, and Cussy reads to him while keeping the pages high, sparing him from having to stare at her face.

Cussy notices something unsettling: Willie’s nails and parts of his foot carry a faint blue tint. Angeline asks Cussy to persuade the doctor to come by offering him precious corn seeds as payment, and she confides that she is pregnant and hopes for a better life for her child.

Danger shadows Cussy’s work. Preacher Vester Frazier confronts her on the trail, condemning her books as sinful and her blue skin as proof of a devil inside her.

He grabs her, tries to force her toward the water, and claims he can “cleanse” her. Junia charges in at the crucial moment, trampling and braying until the preacher flees.

Shaken, Cussy rides on, learning that survival in these mountains often depends on quick instincts, a steady hand, and the fierce loyalty of her mule.

Cussy also meets Jackson Lovett, a newcomer living on a ridge homestead. Their first encounter is awkward—Junia bites him when he reaches for the bridle—but Jackson surprises Cussy by treating the injury calmly and speaking to her with curiosity rather than disgust.

He asks for specific books and shows he values reading, and Cussy finds herself thinking about him long after she rides away. In town, however, cruelty is louder than kindness.

At the library center, supervisors and townspeople mock Cussy’s color and treat her as less than human. She forms a friendship with Queenie Johnson, another Pack Horse librarian who faces brutal discrimination as a Black woman.

Even simple acts—washing a wound, standing side by side—are policed by signs and threats.

Meanwhile, unrest grows in the mining community. Elijah becomes involved in union efforts, desperate for safer conditions and fair pay, and he disappears for stretches of time.

Cussy fears the company’s violence and the way men can vanish without explanation. She clings to scraps of information passed through friends, waiting for proof her father is alive.

At the same time, gossip spreads that Vester Frazier has gone missing. Cussy carries the secret weight of what happened on the trail and the lengths taken to keep her safe from investigation.

A turning point comes when a doctor takes Cussy to Lexington for testing. There, she faces cold stares and clinical distance, but the medical findings give her condition a name: methemoglobinemia, a blood disorder that reduces oxygen delivery and causes the blue coloring.

The doctor offers an experimental treatment—methylene blue injections—that briefly change her skin tone. For a moment, Cussy sees herself in the mirror without the mark that has invited hatred all her life.

But the effect fades, and the physical toll is real. Still, she keeps taking the injections, hungry for a world that might treat her differently if she looks “acceptable.”

Tragedy strikes on Cussy’s route when she finds Willie Moffit dead by hanging and discovers Angeline bleeding after childbirth, with a newborn baby girl beside her. The child has a faint blue tint, revealing the truth Willie could not accept: the “blue” trait was in him, too.

Overwhelmed by shame, he chose death, leaving Angeline and the baby behind. As Angeline fades, she begs Cussy to take the baby—Honey—and raise her with love, because the world will be cruel to a blue child.

Cussy promises, reading aloud as Angeline dies so Honey will hear words filled with life even as loss settles in.

Cussy brings Honey home and argues with Elijah, who fears the scandal of an unwed woman raising a baby. But Cussy refuses to abandon the child.

Elijah relents, and they begin building a fragile family. Cussy arranges care for Honey with Miss Loretta Adams, an elderly woman who welcomes the baby with joy and offers protection while Cussy works.

As Elijah’s health worsens, he again presses Cussy to marry, believing respectability might shield Honey. Then Jackson Lovett returns the old courting candle and admits he has been asking Elijah’s permission for some time.

He proposes, promising to love Cussy and Honey without conditions. Cussy accepts, allowing herself to hope.

They marry at the courthouse with friends nearby—only to have their marriage destroyed minutes later when Sheriff Davies Kimbo arrests Jackson under Kentucky’s miscegenation laws. Jackson is beaten and jailed, the license torn apart, and Cussy is threatened with losing Honey to an institution.

Years later, Cussy writes that she continues her library work and raises Honey, now a bright child eager to read. Jackson, freed but banished from Kentucky for decades, visits secretly from Tennessee.

The prejudice has not vanished, but small changes appear—signs come down, allies remain, and Cussy keeps riding, carrying books, knowledge, and a hard-won kind of hope into the hills.

Characters

Cussy Mary Carter (Bluet)

Cussy Mary Carter, known lovingly as Bluet, is the heart of The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek. She embodies resilience, compassion, and quiet defiance against the social prejudices of her time.

Born with blue-tinged skin caused by methemoglobinemia, she lives on the fringes of society, shunned and ridiculed for her difference. Yet, instead of succumbing to isolation, Cussy channels her pain into purpose through her work as a Pack Horse librarian, bringing books and literacy to the remote Appalachian communities.

Her empathy for the poor and uneducated mountain folk stems from her own experiences with ostracism, making her an agent of change and kindness in a cruel world. Through the novel, she grows from a timid, self-effacing young woman—one who hides her hands and avoids mirrors—into a proud, self-assured individual who embraces her identity and worth.

Her journey is one of reclaiming dignity in a society that equates worth with whiteness, and her enduring devotion to knowledge and compassion becomes her quiet form of rebellion.

Elijah Carter (Pa)

Elijah Carter, Cussy Mary’s father, is a complex figure defined by love, fear, and generational hardship. A coal miner hardened by years underground, he embodies the struggles of working-class Appalachia during the Depression.

His insistence that Cussy marry stems not from cruelty but from a desperate desire to protect her in a world that offers little mercy to women—especially those marked as “other.” His fear of her dying alone or destitute drives his poor choices, including forcing her into a dangerous marriage. Yet beneath his stern exterior lies deep love and vulnerability, revealed in his tender care after Cussy’s assault and his tireless fight for miners’ rights.

Elijah’s participation in union activities symbolizes his yearning for justice and equality, paralleling his daughter’s struggle for acceptance. His eventual softening—accepting Honey as family and supporting Cussy’s independence—marks a quiet redemption and a recognition of his daughter’s strength.

Jackson Lovett

Jackson Lovett stands as the embodiment of compassion, intellect, and moral courage in contrast to the narrow-mindedness that dominates Troublesome Creek. A newcomer and outsider like Cussy, Jackson sees beyond color and class, valuing her for her intelligence, empathy, and bravery.

His growing affection for her is not born of pity but of admiration, making him both a romantic and moral ideal. Jackson’s willingness to defy Kentucky’s miscegenation laws and marry Cussy is a radical act of love and resistance in a segregated society.

His imprisonment and exile underscore the cruelty of institutionalized racism, but his unwavering devotion to Cussy and their child, Honey, reaffirms the novel’s theme that love and humanity transcend man-made boundaries. Through Jackson, Richardson portrays the possibility of decency and moral progress even in dark times.

Angeline Moffit

Angeline Moffit represents the tragic cycle of poverty and prejudice that consumes many Appalachian women. A young wife and mother, she mirrors Cussy’s own yearning for dignity amid hardship.

Her attempts to read, write, and barter with books for medical help symbolize the transformative power of literacy and knowledge in a place that often dismisses their value. Angeline’s death following childbirth—abandoned and scorned because her baby was born with blue skin—lays bare the lethal consequences of ignorance and shame.

Yet, her final act of entrusting her baby, Honey, to Cussy becomes a moment of grace. Through Angeline, the novel exposes how women, especially poor rural women, are often victims of both patriarchy and superstition, but also how they forge deep bonds of sisterhood and compassion in resistance to such forces.

Honey

Honey, Angeline’s infant daughter, becomes a living symbol of hope, continuity, and the shared legacy of the “Blue People.” Her faint blue tint represents both vulnerability and survival—the persistence of difference in a world eager to erase it. In raising Honey, Cussy finds purpose beyond her librarian work; she channels her maternal instincts and her mission for acceptance into nurturing a new generation.

Honey’s existence ensures that the story of the Blues will not die out, and that the love, knowledge, and courage passed on by Cussy will endure. The child’s laughter and innocence soften even Elijah’s hardened heart, turning Honey into a beacon of reconciliation and future promise.

Junia

Junia, Cussy’s mule, is more than a faithful companion—she is a symbolic extension of Cussy herself. Fierce, loyal, and misunderstood, Junia mirrors Cussy’s defiant spirit against male aggression and societal cruelty.

Her protective instincts and aggression toward abusive men, such as Vester Frazier, make her a living shield for her mistress. Through Junia, the novel explores the deep connection between humans and animals, particularly in isolated, rural landscapes where companionship can be a matter of survival.

Junia’s intelligence and devotion emphasize themes of loyalty, freedom, and resilience, offering both physical and emotional strength to Cussy throughout her journey.

Queenie Johnson

Queenie Johnson, a Black Pack Horse librarian, embodies the shared struggle of marginalized women against racial and social oppression. Her friendship with Cussy bridges the racial divide, creating a rare bond between two women who understand what it means to be judged for the color of their skin.

Queenie’s success—earning a librarian position in Philadelphia—highlights both the progress possible through perseverance and the painful contrast between her mobility and Cussy’s continued entrapment in Kentucky’s bigotry. She represents the power of education as liberation, and her respect for Cussy’s courage reinforces the theme of solidarity among women facing systemic injustice.

Queenie’s departure serves as both inspiration and a bittersweet reminder that while some can escape, others must continue to fight where they stand.

Harriett Hardin and Eula Foster

Harriett and Eula represent the ingrained cruelty of small-town prejudice and the moral hypocrisy that festers under the guise of propriety. Harriett’s gossip, mockery, and open racism expose the pettiness of a community eager to ostracize those who are different.

Eula’s complicity, seen in her enforcement of segregationist rules and her “No Coloreds” sign, demonstrates how ordinary people perpetuate systemic injustice under the cover of tradition. Yet, Richardson allows faint hints of humanity—Eula quietly removing the sign in the novel’s closing years—suggesting that even the hardest hearts may soften over time.

These women serve as counterpoints to Cussy and Queenie, illustrating how ignorance sustains cruelty and how knowledge threatens it.

Vester Frazier

Preacher Vester Frazier embodies fanaticism and the weaponization of religion against the vulnerable. A man driven by delusion and sadism, he uses faith to justify violence and sexual aggression, seeing Cussy’s blue skin as evidence of sin.

His attempted “baptism” and assault on her represent the worst form of spiritual and physical abuse. When he dies at Cussy’s hand, his demise becomes both literal and symbolic—a purging of the hate and superstition that plague Troublesome Creek.

Through Frazier, the author critiques the misuse of religion as a tool for control and punishment, and his end underscores the moral triumph of compassion over fanaticism.

Themes

Prejudice and Racial Discrimination

In The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, the most pervasive form of injustice comes from the deep-seated prejudice that defines 1930s rural Kentucky. The novel’s portrayal of Cussy Mary’s life as a “Blue” woman lays bare how ignorance and fear can transform physical difference into social exile.

Her blue skin, caused by methemoglobinemia, turns her into an object of superstition and hatred—people label her as “devil-touched,” refuse to touch her books, and deny her humanity. This discrimination mirrors the racial hierarchies of the Jim Crow South, where both skin color and ancestry determined worth.

Richardson uses Cussy’s experiences to critique the social mechanisms that create “outsiders,” showing how systemic bigotry is reinforced by religion, law, and custom. Even as Cussy works selflessly to bring education to impoverished families, her good deeds are met with violence, exclusion, and humiliation.

The arrest of her husband Jackson Lovett under miscegenation laws underscores how institutionalized racism extends beyond individual cruelty—it is codified into governance and morality. Yet, within this bleak reality, moments of quiet defiance emerge: Queenie Johnson’s success as a Black librarian, and Eula’s eventual decision to remove the “No Coloreds” sign, suggest small ruptures in the wall of hatred.

The novel’s treatment of prejudice becomes a haunting commentary on how ignorance can poison empathy, and how dignity persists even when the world denies it.

Gender and the Role of Women

The story presents women not as passive victims of their circumstances, but as agents of endurance and transformation within a patriarchal society that limits their freedom. Cussy Mary’s fight to remain a Pack Horse librarian despite her father’s insistence on marriage symbolizes the broader struggle for female autonomy during the Great Depression.

Women were expected to obey, marry, and sacrifice ambition for domestic duty; yet, Cussy’s journey on horseback through the mountains becomes both a literal and symbolic assertion of independence. Through her, Richardson illuminates the tension between duty and self-determination—the expectation to serve versus the yearning to live meaningfully.

The Pack Horse women, often dismissed as “unfit” or “unfeminine,” redefine womanhood by carrying knowledge and compassion to isolated homes. Their labor challenges the belief that education and courage belong only to men.

Even within private suffering—Cussy’s forced marriage and sexual assault—there is resistance in survival. Her reclamation of her body, her career, and her right to choose motherhood through adopting Honey, demonstrate resilience born not from privilege but from moral strength.

Richardson’s portrayal of women in this novel celebrates the quiet heroism that sustains communities when men falter, suggesting that progress, though invisible in history books, often begins with the endurance of women who refuse to surrender their purpose.

Poverty and the Power of Knowledge

Economic deprivation saturates the Appalachian landscape of the novel, shaping both the moral and material world of its characters. The residents of Troublesome Creek live in a cycle of hunger, illness, and dependency, where survival eclipses all else.

Cussy’s father, a miner crushed by poverty and corporate exploitation, embodies a generation of working-class men trapped by capitalism’s indifference. Amid this despair, Cussy’s books emerge as lifelines—objects of both hope and defiance.

The WPA’s Pack Horse Library Project, meant to uplift rural America, represents a belief in the democratizing power of knowledge. When Cussy delivers reading material to families like the Moffits or the Smiths, the act transcends literacy; it becomes a moral offering, a way to remind the forgotten that they are worthy of beauty, curiosity, and thought.

Books become medicine for the spirit in a world where food is scarce, teaching children to dream and adults to question their limits. Richardson’s depiction of literacy is not romanticized—it is grounded in the struggle to make learning relevant in a place where hunger gnaws at dignity.

Yet, the persistence of the librarians illustrates that knowledge is the one thing that cannot be confiscated by poverty. Through stories and words, the novel suggests that education is not just escape—it is resistance against the silence imposed by deprivation.

Isolation and the Search for Belonging

Cussy Mary’s journey is ultimately one of seeking acceptance in a world determined to reject her. Her blue skin becomes both her curse and her identity, a mark that isolates her even from those she serves faithfully.

The mountains of Kentucky amplify her solitude—vast, cold, and filled with whispers of superstition. Within that loneliness, the few connections she builds—her bond with Junia the mule, her friendship with Queenie, and her love for Jackson—become acts of salvation.

Richardson explores how isolation, whether physical or emotional, can warp human perception. The townspeople’s fear of Cussy arises from their own loneliness and ignorance, and their cruelty reflects a desperate need to define belonging through exclusion.

When Jackson sees beyond her color, his love becomes a radical recognition of shared humanity, defying the rigid social boundaries of their time. The theme of belonging also extends to Cussy’s relationship with Honey, the blue-skinned baby she adopts; together they form a family built not on blood or conformity, but on acceptance.

Their union stands as a rebuke to a society that confuses sameness with community. By the novel’s end, belonging is no longer about social approval—it is about finding those who see the soul beneath the surface.

Hope, Resilience, and the Human Spirit

Despite the cruelty that surrounds her, Cussy Mary embodies endurance rooted in compassion. The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek becomes a testament to how the human spirit can endure repeated trials without surrendering kindness.

Each loss—her mother, her freedom, her safety—could have hardened her, yet she continues her library route, nurturing curiosity in others even as she faces scorn. Hope in this novel is not grand or romantic; it is quiet, stubborn, and practical.

It appears in the act of reading a story to a child, in Queenie’s promotion, in the slow removal of hateful signs, and in Honey’s first steps. Richardson portrays resilience not as heroic denial of pain, but as the ability to continue loving the world despite it.

The methylene blue injections that briefly make Cussy appear “white” expose the emptiness of external acceptance, reminding readers that true healing lies in self-worth, not in erasure. Even when the law punishes her love for Jackson, she refuses bitterness, choosing to build a home filled with books and tenderness.

Through Cussy, the novel celebrates ordinary endurance as the highest form of courage—an unbreakable faith in goodness despite the world’s determination to destroy it.