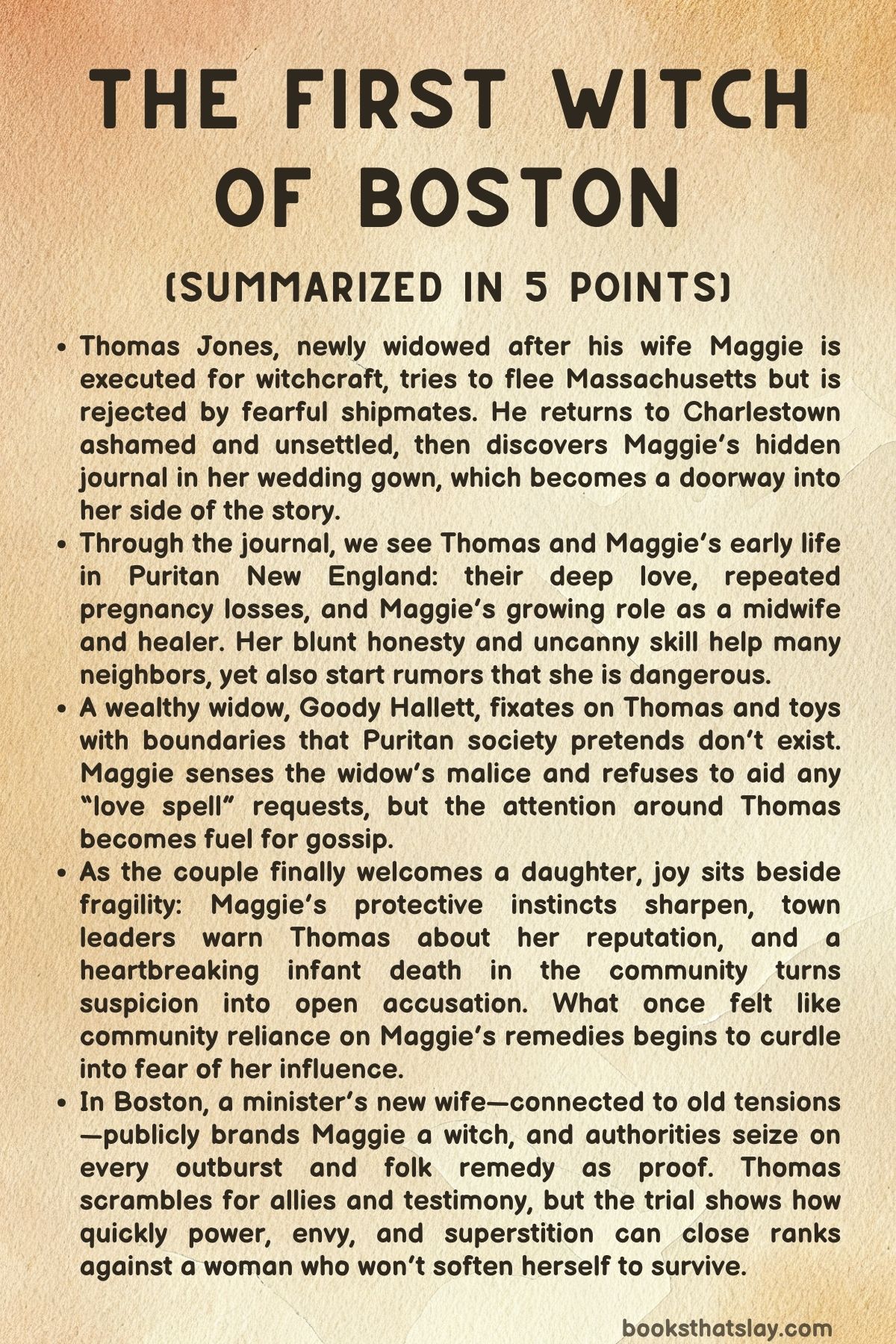

The First Witch of Boston Summary, Characters and Themes

The First Witch of Boston by Andrea Catalano is a historical novel set in Puritan New England, built around the real-life execution of Margaret “Maggie” Jones, often cited as the first woman hanged for witchcraft in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The book follows Maggie, a sharp-tongued healer and midwife, and her husband Thomas, an Irish cabinetmaker, as they try to build a stable life in a society that fears anything it can’t control.

Through Thomas’s grief and Maggie’s own voice in her hidden journal, the story examines love, suspicion, power, and how quickly helpful knowledge can be turned into a death sentence.

Summary

In June 1648, Thomas Jones stands on a Charlestown dock ready to leave Massachusetts for Barbados. His wife, Margaret “Maggie” Jones, has been executed for witchcraft two weeks earlier, and he wants to escape the colony that ruined them.

Yet as he boards the ship Welcome, the passengers recognize him as “the witch’s husband. ” The ship suddenly tilts hard to starboard and will not steady.

Terrified travelers blame Thomas for bringing evil aboard and demand he be thrown off. Though Captain Davies doubts their fear, the ship stays unbalanced until constables escort Thomas back onto the dock with his trunks and his cat, Molly.

The moment his belongings touch land, the ship straightens. The crowd’s certainty grows, and Thomas is left shamed, stranded, and without a home.

With nowhere to go after selling his house, Thomas takes shelter with friends Samuel and Alice Stratton. Alice gently asks whether he still holds anything belonging to Maggie that might keep danger near.

Thomas admits he kept her emerald wedding gown. Late that night he opens his trunk to destroy the last traces of her, honoring her final request.

Hidden inside the folds he finds a small red leather book he has never seen: Maggie’s journal. He hesitates, knowing that even a hint of forbidden knowledge could doom him, but grief pushes him to read.

The earliest pages describe their arrival in Charlestown in 1646 and Maggie’s work as an apothecary preparing salves, teas, and remedies for neighbors. Her voice is practical, loving, and confident.

For Thomas, the words revive his memories of her warmth and skill, while also raising a frightening question: did this book contain anything that could have been twisted into “witchcraft”?

The journal carries Thomas back to their life two years earlier. In June 1646, Maggie and Thomas lie together after making love.

She is certain she is pregnant again after repeated losses, claiming she has dreamed of a strong baby girl. Thomas wants to believe her but has learned caution through heartbreak.

Their hopes are simple: a safe home, a child, and a chance to live quietly.

Thomas’s carpentry business grows, bringing him into Boston to meet Goody Hallett, a wealthy young widow who wants a large wardrobe built. She guides him into her bedchamber, openly flirtatious, and offers payment without bargaining.

Thomas leaves uneasy, aware that a bold woman in Puritan society can be dangerous to be near. When he tells Maggie about the job, he stresses that she alone is his love.

Maggie believes him, but she senses something cold in the widow. Later Hallett visits Maggie for herbs and hints that she wants a love spell so men cannot resist her.

Maggie refuses sharply, warning that such talk invites ruin. She comes away convinced that Hallett’s desire for Thomas could turn into malice.

As Maggie’s pregnancy progresses, her reputation in Charlestown becomes complicated. She is gifted and blunt; her cures often work, and she sometimes seems to know an ailment before a patient speaks.

Neighbors admire her results, but they worry about her methods and her directness. In August 1646, Thomas finds Maggie in the market giving strawberries to a young man locked in the pillory for Sabbath drunkenness.

The act is compassionate, yet public. Former governor Endecott calls her a “cunning woman” and orders her away, implying the Devil’s influence.

Thomas defends her, blaming pregnancy softness, but Endecott warns that her kindness toward sinners will cost them fines and scrutiny.

Through autumn and winter their household brightens. Maggie delivers twins for Goody Moore, managing the birth skillfully and using poppy to calm a violent husband.

That night Thomas waits under a full moon and remembers their first meeting in England years ago at a Midsummer festival by the chalk White Horse. They had slipped away from the bonfires, made love, and promised marriage before dawn.

The memory reminds him that their bond began with joy and trust, long before fear ruled their lives.

By December 1646, Puritan authorities have banned Christmas, but Maggie and Thomas quietly celebrate her growing belly. She is sure the baby is a girl and speaks of naming her Elizabeth.

Her moods are sharp, and her confidence in her healing grows stronger, which others interpret as arrogance. Whispers spread again: “cunning woman” is a step away from “witch.

” Still, in March 1647 she gives birth after a long labor. The baby girl arrives healthy, if oddly shaped from birth.

Alice Stratton reassures Thomas that newborn skulls round out. They name her Elizabeth, called Bess, and for a while the family seems safely anchored.

Motherhood is harder than Maggie expected. She fears she is failing because Bess cries with hunger, though Thomas points out the baby is thriving.

They find brief moments of intimacy and laughter again. Thomas’s work prospers.

Yet Hallett remains a shadow. She commissions a massive bed and needles at Maggie with the label “cunning woman.

” Thomas throws her out of his shop, but the insult sticks. When Hallett later touches Bess, the child becomes fussy and feverish.

Maggie worries about the Evil Eye and protects Bess with charms of rue and oils. The child is only teething, but Maggie’s protective rituals, common in her old life, look ominous to Puritan eyes.

Warnings come from above. Governor Winthrop and former governor Dudley tell Thomas that Maggie’s sharp tongue and strange intuition need restraint.

Sam Stratton repeats that neighbors talk behind their backs. In October 1647, Maggie treats the Weston boy’s croup using methods she knows well—warmth, open windows, and forceful coughing to clear the chest.

The boy improves, but his mother is unsettled by Maggie’s talk of “ill humors” and her commanding tone. Thomas argues with Maggie, pleading for caution.

They reconcile, but the social ground beneath them keeps crumbling.

The worst blow lands in December. Maggie delivers Goody Hall’s baby, but it is stillborn, dead from a cord around its throat.

Maggie comes home mourning. After church three weeks later she approaches Goody Hall to offer comfort.

The woman recoils and cries out publicly that Maggie is the Devil’s hand. Even Goody Hall’s husband supports the claim.

The congregation stares, and Thomas feels the colony’s quiet suspicion harden into threat.

By 1648 the danger becomes open. Maggie quarrels with Goody Pierce over cruelty toward her cat, and Pierce storms away calling her devilish.

Maggie also angers Governor Winthrop by praising native remedies after an elderly Winnisimmet woman shows her a medicinal plant. Winthrop scolds her for trusting Indigenous knowledge; Maggie fires back that native people once saved starving colonists.

Each honest sentence makes her enemies stronger.

At Sunday service the new minister Longfellow preaches, and Maggie notices his wife is the former Widow Hallett—now “Goody Longfellow”—and already pregnant. Maggie hints aloud that the child was conceived before marriage.

Thomas hushes her, watching Hallett stare at him with unreadable intent. Soon after, Mary Doyle, the minister’s servant, secretly brings Maggie a poppet found in Hallett’s wardrobe.

The doll resembles Maggie, and thirteen pins pierce its belly. Maggie believes Hallett wants to curse her womb and may have helped kill Bess, who died of scarlet fever at fourteen months.

Maggie wants confrontation; Thomas refuses, fearing that accusing a minister’s wife without backing would destroy them.

The next week in the marketplace, Hallett strikes first. She publicly screams that Maggie has bewitched her, clutches her head, and faints dramatically.

The town accepts the spectacle as proof. On May 12 constables arrive with a warrant charging Maggie with witchcraft, dealings with Satan, harming townspeople with her medicines, and keeping familiars.

Maggie laughs and fights them verbally, and her fury is recorded as evidence. She is hauled to jail.

Thomas, desperate, gathers names of people Maggie healed and pleads with former governor Bellingham. Bellingham sympathizes but says Winthrop and the magistrates are determined, and that Maggie must appear humble or the court will crush her.

At trial Maggie stands chained before nine magistrates led by Winthrop and Dudley. She refuses silence, challenging every charge.

Witnesses describe her treatments as spells. A boy says she opened windows on a cold night and ordered illness to leave; his mother calls it sorcery.

Goodman Spence admits Maggie gave him an oil to prolong sex, then claims it ruined his marriage when his wife’s desire rose and she ran away. Maggie names the ingredients plainly, but the court treats her knowledge as corruption.

Her defiance feeds their certainty.

That night Maggie is watched by Constable James Baldwin. Feverish from sickness and grief, she speaks of Bess as if the child is alive beside her.

A frightened maid claims she sees the child too, then collapses into a seizure. Maggie orders James to fetch a spoon and saves the maid from choking.

When Molly the cat enters and curls near Maggie, James is shaken. The next day these events are used against her.

A professional witchfinder, Martha Wheeler, says she found a “witch’s teat” on Maggie’s thigh that did not bleed when pricked. Maggie denounces the tool as fraud, but the crowd roars.

James testifies about the night visions. The magistrates call it proof.

Winthrop announces the verdict: Maggie is guilty and will be hanged on June 15, 1648. In jail she is sick, isolated, and still unbroken.

A constable assaults her the night before execution, attempting rape, but Governor Bellingham interrupts, arrests the man, and grants Maggie one last night with Thomas. In the cell Thomas confesses that Hallett drugged his ale and seduced him, and he believes her pregnancy is his child.

Maggie is shattered with rage and sorrow, yet their love survives the shock. She makes him swear to leave Massachusetts, destroy their possessions, and refuse to let her death trap him.

Hallett visits to gloat, claiming she helped turn the court and that she carries Thomas’s baby. Maggie presses the cursed poppet into her hand and warns that evil returns threefold.

Hallett flees, shaken. On execution day storm clouds gather.

Maggie stands on a cart beneath a maple tree, declares her innocence, and denounces the court. Alice Stratton cries out in protest, but the cart rolls away and Maggie dies by hanging, giving Thomas a last farewell.

Later, Thomas finds a hidden letter Maggie wrote on the day of her arrest. She reveals a secret she never spoke aloud: as a teenager in England she was raped, became pregnant, refused abortion, and gave birth at fifteen.

Her grandmother took the baby to be adopted by the Wells family. Bess was Maggie’s second daughter.

With that truth, Thomas’s grief turns into purpose. He leaves for Maryland, then learns Hallett died in childbirth and Reverend Longfellow killed himself.

Two years after Maggie’s death, Thomas returns to England, finds Maggie’s first daughter Constance at the Wells farm, and tells her who her mother was. He offers her money and a chance to begin again in Maryland.

She hesitates but later appears at Bristol harbor as his ship prepares to sail. Thomas welcomes her aboard, calling her his daughter, and at last carries Maggie’s legacy forward into a freer life.

Characters

Thomas Jones

Thomas is the emotional anchor and point-of-view lens for much of The First Witch of Boston, a man pulled between private loyalty and public terror. He begins as a practical Irish cabinetmaker who believes hard work and migration can secure a decent life, but his wife’s persecution forces him into a far more fragile role: widower, exile-in-waiting, and reluctant keeper of her memory.

What makes Thomas compelling is not heroic certainty but human contradiction. He deeply loves Maggie and often defends her, yet he also fears the Puritan system enough to urge restraint, and his caution sometimes reads like betrayal to her.

His shame after being cast off the Welcome shows how quickly communal hysteria can strip him of dignity; in that humiliation he becomes a symbol of collateral damage in witch trials, punished not for deeds but for proximity. His confession of infidelity is not framed as simple lust, but as a moment of weakness exploited by Hallett and then weaponized by the town.

The epilogue completes his arc: grief hardens into purpose. By seeking Maggie’s first daughter and remaking his life in Maryland, Thomas transforms from a man who tried to survive quietly into one who carries truth forward, suggesting that love for Maggie ultimately reshapes his identity into something braver than he knew he could be.

Margaret “Maggie” Jones

Maggie is the novel’s fiery center: an apothecary and midwife whose competence, intuition, and refusal to bow make her both luminous and doomed in Puritan Massachusetts. She lives in two realities at once.

In private, she is devoted wife and mother, aching from miscarriages and later from Bess’s death, and her tenderness surfaces most clearly when she delivers babies or comforts the sick. In public, she is sharp-tongued, proud, and impatient with ignorance, and that bluntness becomes her fatal vulnerability in a culture that equates female assertiveness with moral danger.

Maggie’s “uncanny” diagnostic gift is written as a natural extension of experience and empathy, yet the town reads it as diabolical; this gap between what she knows herself to be and what society insists she is fuels the tragedy. She also carries a buried personal history of sexual violence and coerced motherhood, which explains both her fierce self-protection and her complicated sense of womanhood.

Importantly, Maggie never offers the submission that might save her. Even in chains and fever, she resists being rewritten into a repentant stereotype.

Her final defiance, her refusal to confess, and the dark tenderness of her last night with Thomas make her more than a victim: she becomes a moral indictment of the world killing her.

Molly

Molly, Maggie’s plump multicolored cat, functions as far more than a pet in The First Witch of Boston. She embodies the ordinary domestic life Maggie and Thomas try to preserve, yet in the eyes of the community she becomes proof of supernatural threat.

The contrast is deliberate: to Maggie, Molly is comfort, continuity, and companionship; to the Puritan crowd, she is a familiar, a living symbol onto which fear can be projected. Her calm presence during Maggie’s imprisonment—padding in, rubbing against her, seeming to seek her out—reads naturally as animal loyalty but is interpreted by constables as eerie allegiance.

In that way Molly exposes the mechanics of hysteria: anything affectionate or unexplained becomes sinister when a narrative of witchcraft is already in motion. She also adds emotional texture to Thomas’s grief after Maggie’s death, because caring for Molly links him to Maggie’s last requests and to the life they lost.

Goody Hallett / Goody Longfellow

Hallett is the novel’s most overt antagonist, but she is not simply evil; she is ambition wearing piety’s mask. As a young, wealthy widow, she is accustomed to desire turning into entitlement, and her pursuit of Thomas is both sexual and strategic.

Her flirtation in his workshop and the way she hovers around Maggie are acts of dominance, testing how far she can transgress without consequence. Once she becomes Reverend Longfellow’s wife, her power multiplies, and she weaponizes Puritan structures to eliminate Maggie—the woman who saw through her and refused to help her chase vanity spells.

The poppet in her wardrobe, her marketplace theatrics, and her influence over testimony show a knack for manipulating superstition into policy. Yet beneath her machinations is something almost pitiful: she wants to be irresistible, to be chosen, to win.

Her final fate—dying in childbirth—mirrors Maggie’s maternal suffering and suggests the novel’s bleak moral symmetry: cruelty does not cancel vulnerability, and the same society that empowers her also devours her.

Reverend Longfellow

Reverend Longfellow is the institutional face of righteousness turned lethal. Frail in body but absolute in authority, he represents the Puritan belief that social order is spiritual order.

His marriage to Hallett ties him to personal corruption he seems unwilling or unable to see, and his rapid readiness to denounce Maggie shows how fragile clerical compassion can be when reputation and orthodoxy feel threatened. Longfellow’s courtroom posture is less about truth than about protecting a worldview where misfortune must have a moral cause.

His eventual suicide in the epilogue implies a delayed reckoning: either guilt finally pierces him or the collapse of his marriage and public life proves too heavy. In either case, his arc reflects the cost of complicity, even for those who believe themselves righteous.

Samuel Stratton

Samuel is a steady, quietly courageous counterpoint to the colony’s fear. As Thomas’s friend and host after the Welcome incident, he provides practical refuge when Thomas is most desperate.

Samuel is not flamboyantly defiant toward the authorities, but his loyalty is consistent and risky: he helps Thomas gather testimony, repeats uncomfortable rumors without malice, and continues to stand by the Jones family even as suspicion rises. His role underscores that resistance in such a society often looks like persistence—offering shelter, speaking gently against gossip, and refusing to abandon the accused.

Samuel is also a portrait of ordinary goodness under pressure, a man who understands the danger yet chooses friendship anyway.

Alice Stratton

Alice is one of the novel’s strongest secondary moral voices, embodying female solidarity within a rigid world. As midwife and confidante, she validates Maggie’s skill and maternity, helping deliver Bess and offering comfort through loss.

Alice’s blessing of Maggie’s pregnancy and her stories of late-life childbirth function as emotional medicine, balancing Maggie’s own sharpness with warmth. Importantly, Alice is not blind to danger; she asks Thomas what relic of Maggie he still holds, intuiting how memory can become perilous in a fearful town.

Her outcry at Maggie’s execution is a rare public rupture of the Puritan script. Alice represents what the colony suppresses: women supporting women against the state’s gaze, even when silence would be safer.

Bess (Elizabeth Jones)

Bess is both presence and absence, the child around whom love and grief crystallize. Her birth is a triumph after repeated loss, and her early life is portrayed as vigorous and hungry for the world.

The death of Bess from scarlatina becomes the emotional pivot of the story. For Maggie, it is a wound that never closes and a trigger for her fever-dream in jail, where motherly love and trauma blur into visions that the court will distort into witchcraft.

For Thomas, Bess’s loss weakens his ability to protect Maggie because it intensifies his fear of further punishment. Bess is also the vulnerable point Hallett attacks through the poppet, making her death part of the larger machinery of accusation.

Even in death, Bess drives the plot, proving how child loss in this world is never private—it becomes public evidence, rumor, and weapon.

Constance Wells

Constance appears late but reframes the entire narrative. She is Maggie’s first daughter, taken away after Maggie’s teenage rape and pregnancy, and raised without knowledge of her origins.

When Thomas finds her, she becomes a living bridge between Maggie’s silenced past and her erased future. Constance’s resemblance to Maggie is not just physical; it carries the implication that identity survives persecution.

Her initial refusal to leave England shows a cautious independence, not sentimentality, yet her later decision to board Thomas’s ship suggests a willingness to reclaim a legacy once she understands it. Constance embodies continuation: the life Maggie was denied now has a chance to unfold beyond the reach of Boston’s gallows.

Governor John Winthrop

Winthrop stands for the paternal authority of the colony—cultured, politically savvy, and profoundly certain that spiritual purity justifies coercion. His early correction of Maggie for listening to Indigenous knowledge reveals the ideological frame that will later condemn her: anything outside sanctioned doctrine is suspect.

Winthrop’s leadership in the trial is not cartoonish cruelty but bureaucratized fear. He interprets laughter, anger, and sickness as guilt because his system requires witches to exist to explain disorder.

His power lies in how calmly he transforms prejudice into verdict. In the novel’s moral universe, Winthrop is less a villainous individual than a mechanism, the voice of a society that prefers certainty over compassion.

Governor Richard Bellingham

Bellingham is a conflicted protector, caught between conscience and survival within politics. He believes Maggie is not a witch and assists Thomas with advice and limited help, even intervening dramatically to stop Constable Johnson’s assault.

Yet he repeatedly hedges, refusing to testify personally and warning Thomas about the political costs of open defense. This mixture of sympathy and self-preservation makes him one of the story’s most realistic figures.

Bellingham illustrates how decent people can enable injustice by trying to do “just enough” without burning their own standing. His care for Maggie in her last night is genuine, but his inability to stop the execution shows the limits of private virtue in a public machine.

Thomas Dudley

Dudley functions as a hard-edged judicial partner to Winthrop. He is the magistrate who reads charges and treats Maggie’s interruptions as proof, showing a temperament that values order over inquiry.

Dudley’s presence highlights how trials are performances: his sternness cues the crowd on what to feel, and his framing of evidence shapes interpretation before Maggie can speak. He is not explored deeply as a personal character, but as a force he represents the colony’s punitive certainty, the kind of man for whom law is not a search for truth but a tool to maintain fear-based stability.

Constable James Baldwin

James Baldwin is a rare point where the system briefly allows empathy to breathe. As Maggie’s overnight guard, he approaches her with skepticism but not hostility, and their shared grief over lost children opens him to her humanity.

His testimony later is devastating precisely because he believes he is being honest. James does not invent what he saw; he interprets a fevered mother’s delirium through the only lens the colony gives him.

This makes him tragic rather than malicious. He embodies how ordinary men, even kind ones, become instruments of brutality when fear provides the story and authority provides the stakes.

Goody Martha Wheeler

Martha Wheeler is the professionalization of witch-hunting. As a witchfinder, she turns suspicion into craft, using body examinations and pricking devices that claim scientific authority while serving superstition.

Her certainty about the “witch’s teat” demonstrates the predatory logic of her trade: the body must yield evidence because the verdict is already assumed. Wheeler does not need to hate Maggie personally; her role depends on producing witches.

She represents an economy of fear, where social panic becomes a livelihood, and where female bodies are policed by other women acting on behalf of male power.

Constable Johnson

Johnson is the story’s blunt depiction of violence unrestrained by morality. His attempted rape of Maggie, accompanied by threats and humiliation, reveals the underside of Puritan authority: a world that publicly preaches virtue while privately enabling cruelty.

Unlike James Baldwin, Johnson does not misinterpret; he abuses knowingly. His dismissal by Bellingham is one of the few moments where the narrative grants immediate justice, but that justice is narrow and arrives too late to save Maggie.

Johnson’s presence underscores that accusations of witchcraft often coexist with, and distract from, real crimes committed by men shielded by power.

Mary Doyle

Mary Doyle, the minister’s servant, is a small but crucial witness to hidden malice. She brings Maggie the poppet with pins, acting out of fear and perhaps conscience.

Mary’s choice to reveal the doll suggests she suspects her mistress’s duplicity, yet her social position prevents her from acting openly. She highlights the peril of truth in a hierarchical society: even seeing wrongdoing does not grant you the power to stop it.

Through Mary, the novel shows how servants and lower-status women become silent carriers of dangerous knowledge.

Minor townspeople and authority figures

Several additional figures operate as a chorus of pressure around the central tragedy. Governor Endecott, by publicly labeling Maggie a “cunning woman,” shows how elite men seed suspicion through small humiliations that later grow into capital charges.

Goody Pierce, Goody Hall, and other neighbors embody how personal offense, grief, and envy mutate into accusation once witchcraft becomes a socially approved explanation for pain. Goodman Spence illustrates opportunistic blame: he enjoys Maggie’s remedies until his household collapses, then repackages his shame as evidence against her.

Goody Moore and the pillory scene show Maggie’s instinctive compassion clashing with Puritan ideas of deserved suffering. Together these minor characters create the social ecosystem of the trials, reminding us that Maggie is not destroyed by one enemy alone but by a community that finds safety in scapegoating.

Themes

Puritan Fear and the Machinery of Social Control

From the moment Thomas is blamed for the ship’s imbalance simply because he is “the witch’s husband,” the story shows how fear can harden into a public system that polices belief and behavior. In The First Witch of Boston, collective anxiety is not a background mood; it becomes an authority that steers decisions, reputations, and even physical safety.

Charlestown and Boston are portrayed as communities where religious doctrine has fused with civic power, so suspicion works like law. Ordinary events—an ill-timed illness, a fainting fit, a cranky infant, a strange birthmark—are read through a single lens: the Devil must be at work.

Once that lens is accepted, it does not matter how thin the evidence is. The court searches for “witch’s teats,” neighbors repeat rumors, and magistrates translate any emotional display into guilt.

Maggie’s laughter in court, her anger, her refusal to be meek: all are treated as confirmations of witchcraft because the society already needs her to be a witch.

This theme also comes through in how quickly social control targets anyone who disturbs the Puritan ideal of restraint. The community doesn’t only punish alleged magic; it punishes difference.

Maggie’s bluntness, medical confidence, and refusal to flatter the powerful make her a threat to a culture that prizes quiet obedience. Even Thomas, a man trying to live within the rules, is vulnerable once connected to her.

The harbor incident makes clear that superstition is less about sincere belief than about enforcing a shared narrative. The passengers could not tolerate uncertainty and seized a socially convenient explanation.

In that sense, fear becomes a tool for keeping the community unified, even if that unity requires cruelty. The tragedy is that the system feeds itself: each accusation raises the temperature of panic, each panic demands another scapegoat.

Maggie’s execution is therefore not just the end of her life; it is the clearest evidence of how a society can legalize its own terror and call it righteousness.

Gender, Authority, and the Cost of Female Independence

Maggie’s life is shaped by what happens when a woman refuses to shrink herself for male comfort. She is a healer, a midwife, and a sharp observer of hypocrisy, and every one of those qualities puts her at odds with the expectations surrounding Puritan womanhood.

The story repeatedly shows that competence in a woman is unsettling to a patriarchal order. Maggie knows remedies before patients speak; she understands births in ways magistrates never could; she sees through the performative piety of people like Goody Longfellow.

Yet instead of being treated as a community asset, her skill becomes evidence against her. The label “cunning woman” is weaponized precisely because it sits at the border of permitted female labor and forbidden female power.

A midwife is acceptable when she is humble and invisible; she becomes dangerous when she is confident, outspoken, or admired.

The contrast between Maggie and Goody Hallett/Longfellow sharpens this theme. Hallett uses the limited forms of power available to women—sexual allure, kinship ties, social performances—to gain protection and influence.

Maggie rejects those methods and insists on frank speech, medical knowledge, and moral clarity. The society is willing to tolerate the former because it doesn’t challenge male governance; it violently rejects the latter because it does.

Even the courtroom becomes a gendered stage: Maggie is condemned not only for alleged magic but for refusing the submissive posture that might have saved her. Bellingham warns Thomas that contrition is required, meaning a type of femininity must be performed in order to survive.

Maggie will not perform it, so her fate is sealed.

The theme extends to sexual control and vulnerability. Maggie carries the hidden trauma of teenage rape, a history that illustrates how female bodies are treated as sites of conquest, shame, and secrecy.

Later, the attempted assault in jail shows the same logic at work: a woman marked as “witch” is also marked as disposable. The story does not present Maggie as flawless, but it frames her defiance as human dignity in a world that confuses obedience with virtue.

Her death becomes an indictment of a culture that cannot imagine female independence without calling it evil.

Marriage, Desire, and the Weight of Grief

At the heart of the narrative is a marriage that is tender, sensual, and battered by loss. Thomas and Maggie’s relationship in The First Witch of Boston is not idealized; it is shown through everyday affection, quarrels, reconciliations, and shared dreams.

Their longing for a child, after repeated miscarriages, creates a foundation of hope that keeps returning even as tragedy piles up. The birth of Bess feels like a victory over fate, and her later death becomes the emotional crater that fear and rumor fall into.

Maggie’s delirium in jail—speaking to Bess as if alive—is both a symptom of fever and a portrait of a mother whose love has nowhere left to go. This grief is private and intimate, yet the community turns it into public evidence of guilt.

Desire inside the marriage is treated with equal complexity. Thomas is deeply devoted, but his attraction to Hallett and eventual affair show how vulnerability can be exploited.

The story doesn’t use this to cheapen their bond; instead it reveals how external pressure and internal loneliness can twist even strong love. Maggie’s anger when she learns the truth is scorching, yet the scene quickly returns to the core of their connection: they are two people who have survived pain together and still reach for each other.

That oscillation between hurt and closeness makes their marriage feel lived-in rather than symbolic.

The theme also highlights how grief reshapes identity. Maggie, once confident in her role as healer and mother, begins to question herself when Bess is gone and the town’s whispers grow louder.

Thomas, once focused on building a stable life, becomes a man driven by memory and responsibility to Maggie’s last wishes. The epilogue carries this forward: grief is not ended by death; it becomes a mission.

Thomas’s search for Maggie’s first daughter is a way of refusing to let love be erased by a courtroom sentence. In that sense, marriage in the book is both shelter and wound, a place where human weakness and loyalty coexist, and where grief tests love without fully destroying it.

Knowledge, Healing, and the Clash Between Medicine and Superstition

Maggie’s apothecary work sits at the center of the conflict, and it exposes how fragile the boundary is between science and suspicion in a theocratic society. She uses herbs, poultices, charms, and practical midwifery skills learned through experience.

None of these are presented as magical in themselves; they are grounded in the bodily realities of illness and childbirth. Yet the Puritan world around her lacks the conceptual space to treat female medical knowledge as legitimate.

When she talks about “ill humors,” or when she beats a boy’s back to clear his lungs, her methods are interpreted as occult because they are not sanctioned by male authority. The story shows how superstition grows in the gaps left by ignorance, and how quickly those gaps are filled with moral panic.

There is also a colonial dimension to this theme. Maggie learns from a Winnisimmet woman about a medicinal plant, and Winthrop’s rejection of that knowledge reflects a wider refusal to credit Native expertise.

Healing becomes political: accepting Indigenous medicine would mean admitting colonists do not own all truth. Maggie’s defense of Native help during earlier famines is therefore not just a personal opinion; it is a challenge to the settled hierarchy of who is allowed to know.

The episode with the poppet underlines how symbolic objects can override material reality. A doll with pins, probably planted by Hallett, becomes proof of a curse because the community is eager to treat symbols as facts.

Likewise, the “witch’s teat” claim depends on pseudoscientific inspection methods imported from England. The court’s approach parodies medicine: it imitates the form of investigation while being driven by predetermined conclusions.

Maggie’s real healing skills are discounted, while fraudulent “witchfinding” is amplified.

Through this conflict, the book frames knowledge as something contested, not neutral. Maggie’s expertise threatens those who depend on fear to maintain order.

Her fate suggests that societies sometimes destroy healers not because the healers are harmful, but because their knowledge exposes the community’s deeper insecurities. The tragedy is that practical care for bodies is treated as spiritual threat, and the people who most need healing participate in condemning the one who provides it.

Scapegoating, Reputation, and the Legacy of Truth

Reputation functions like currency in the towns of Massachusetts Bay, and the story shows how easily that currency can be stolen. Maggie is turned into a scapegoat through a chain of small social fractures: a harsh remark to Goody Pierce, a public comfort offered to a grieving mother, a refusal to supply a love spell, a moment of frankness about Hallett’s pregnancy.

Each incident on its own is trivial. Together they form a narrative that the community finds convenient.

Scapegoating here is not a sudden frenzy; it is a slow social decision to place one person at the center of everyone else’s anxieties. Maggie becomes the vessel for fears about illness, female sexuality, child mortality, and religious impurity.

Thomas’s experience after her death shows the long tail of scapegoating. Even when he tries to leave, the town brands him, the harbor rejects him, and he is forced to walk with the shame designed for his wife.

That stigma reveals that scapegoating rarely stops with the accused; it spreads to anyone linked to them, ensuring isolation and silence.

The epilogue adds another layer: truth can outlive reputation, but only through painful uncovering. Maggie’s hidden letter about her rape and first child reframes her life, not by turning her into a saint, but by restoring her complexity.

The secrecy she carried was born from a world that would have punished her for being a victim. Her decision to keep that truth private makes sense in context, and the letter’s discovery is a reminder of how many lives are misread because the powerful control the story.

Thomas’s mission to find Constance is thus a refusal to accept the official record. He reconstructs Maggie’s identity against the verdict that tried to define her forever.

This theme ends on a note that is both sorrowful and hopeful. The community that killed Maggie collapses into its own consequences—Hallett dead in childbirth, Longfellow dead by suicide, Thomas gone—suggesting that reputational violence corrodes the society that practices it.

Yet Maggie’s legacy travels forward through Constance and through Thomas’s remembrance, showing that truth does not depend on courts to survive. It depends on people who keep telling the fuller story even when the world insists on a simpler lie.