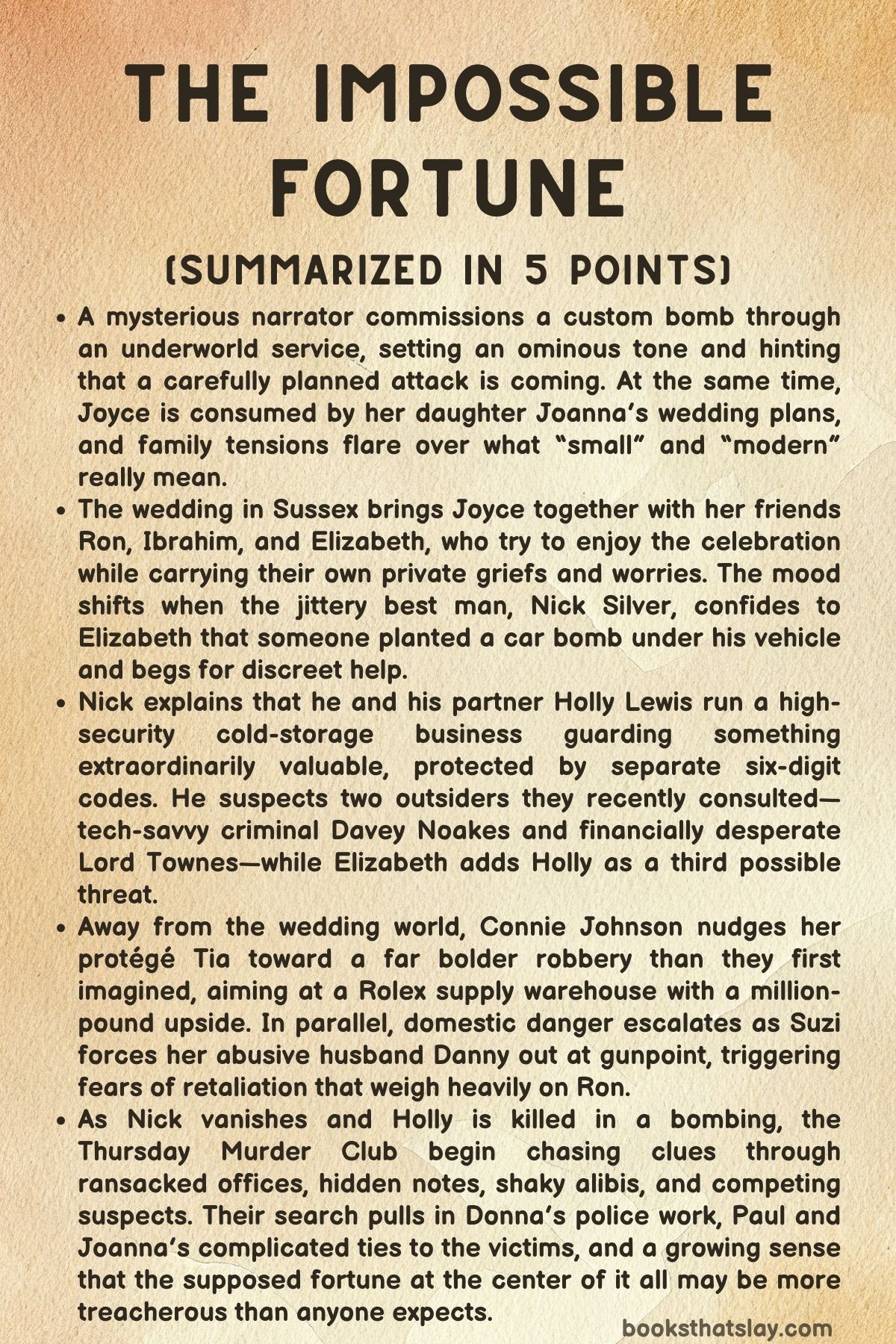

The Impossible Fortune Summary, Characters and Themes

The Impossible Fortune by Richard Osman is a witty, fast-moving mystery that reunites the sleuths of Coopers Chase for another case that’s bigger, messier, and more personal than they expect. The story opens with a chilling hint of violence, then swings into the familiar warmth of friendship, stubborn curiosity, and everyday life among retirees who refuse to stay out of trouble.

When a wedding guest turns up with news of a bomb under his car and a secret tied to a vast crypto stash, the Thursday Murder Club finds itself chasing a vanishing man, a deadly betrayal, and the uncomfortable question of whether any fortune was real to begin with. It’s the 5th book in the Thursday Murder Club series by the author.

Summary

A hidden narrator calmly explains how simple it is to buy instructions for explosives online and even simpler to outsource the job. They choose a compact device and place an order with a criminal outfit that builds and delivers bombs to specification, charging a fortune per target.

The narrator treats the expense like a detail that won’t matter once their plan is complete.

Joyce is distracted by the chaos of preparing her daughter Joanna’s wedding. She wants tradition and grandeur; Joanna wants modern music, no hymns, and a guest list that Joyce considers tiny but is still hundreds strong.

Their bickering softens when they remember Joanna’s late father, Gerry. Joyce throws herself into the event anyway, determined to make it special.

The wedding happens on a Thursday at a beautiful Sussex country house. Joyce, Ron, Ibrahim, and Elizabeth sit together afterward with drinks, watching the evening settle.

They toast the couple, tease one another, and try to enjoy the calm.

Elizabeth lingers outside a moment longer, still hollowed by grief for her husband Stephen. A man approaches her from the trees: Nick Silver, the groom’s best man.

He says someone tried to kill him that morning. He shows her photos of a professional device fixed under his Lexus.

He didn’t remove it because he had to attend the wedding and didn’t want to alert anyone. Nick asks Elizabeth for quiet help, insisting police attention would endanger his work.

He runs a high-security storage venture called The Compound, and something of immense value sits in cold storage there. The secret is locked behind two separate six-digit access codes: one known only to Nick, one only to his partner Holly Lewis.

Each has left sealed backups with a solicitor, to be opened only if one of them dies. In the last week they told two outsiders about what was inside: Davey Noakes, a notorious former drug dealer turned tech criminal, and Lord Townes, a broke aristocratic banker.

Nick believes one of them planted the device. Elizabeth coolly notes that Holly, who possesses the other code, is also a plausible suspect.

Nick asks her to meet the next day so he can explain everything.

Back in Fairhaven, Connie Johnson—recently freed after a mistrial and nudged by Ibrahim into mentoring young offenders—meets her protégé Tia Malone. Tia wants Connie to join a robbery worth a hundred thousand pounds.

Connie pushes her to think larger. Through sharp questions and lessons from Connie’s own past, she persuades Tia to aim at a Rolex supply warehouse instead, worth far more.

Tia begins gathering a crew.

At the wedding reception Joanna privately admits to Ibrahim that she’s scared; she has known Paul only six months. Ibrahim tells her that seeking advice already shows she knows her own heart.

Joyce later writes with delight about walking Joanna down the aisle to a Backstreet Boys song, about Paul’s kindness, and about the way Elizabeth seems secretive. In a separate thread, Suzi Lloyd confronts her abusive husband Danny at home, holding his gun on him.

She has packed his bag and tells him to disappear before her brother Jason arrives. Kendrick, their son, comes downstairs, asks blunt questions, and accepts Suzi’s promise that Danny will not return.

Danny leaves fuming, quietly imagining revenge.

The next morning Elizabeth travels to Fairhaven with Joyce to meet Nick. They find his office at 8b Templar Street looking derelict.

No one answers the buzzer. Joyce notices steam from a vent, suggesting someone is inside.

Elizabeth calls Donna De Freitas. Donna arrives with Bogdan and forces entry.

Inside, the office has been torn apart and Nick is gone. Elizabeth keeps the wider police away, shares her three suspects, and asks Joyce to invite Holly to dinner while they wait for contact.

Before leaving, Elizabeth finds a hidden file addressed to her with a note from Nick: “Help me, Elizabeth. You’ll work out how.

” It convinces her he was alive during the break-in.

Ron, newly hungover and increasingly worried about his daughter Suzi, helps Elizabeth and Joyce search for Nick’s house. His car is there, but the device has been removed.

Nick has vanished without a trace.

Detective Chris Hudson, irritated that the Thursday Murder Club is back in his orbit, handles other murders while Donna keeps chasing leads on Nick and Holly. Soon news arrives: Holly Lewis has been killed by a car device.

Elizabeth and Joyce visit Lord Townes at his decaying estate. Townes admits Holly and Nick came seeking help to convert an enormous cryptocurrency holding—hundreds of millions—into cash.

He expected a massive fee. He tries to sound shocked by Holly’s death and Nick’s disappearance, but the women don’t buy it.

They leave believing Townes has motive and is hiding something.

Danny, now abroad, hires a contract killer to murder Jason first and then Suzi. At Coopers Chase, the club argues about the case.

Ron suspects Nick might be manipulating events; Ibrahim wants access to the codes at The Compound. They add a Manchester contact, Jill Usher, to their suspect list, until Donna discovers that Jill’s husband Jamie has a fraud record and likely was the real contact.

Tia, meanwhile, slips into the Rolex warehouse under a cleaner identity, smuggling in two guns, and waits for the delivery that will kick off her heist.

The club confronts Davey Noakes late at night. Davey admits Holly met him the day before she died.

He says Holly confessed she had tried to kill Nick so she could claim both codes and the whole fortune. Davey refused and removed the device from Nick’s car.

When he couldn’t find Nick afterward, he had one of his men place the device back into Holly’s car with a note meant as a warning. Holly got in, and it detonated.

Davey insists he wanted to scare her, not kill her, and believes Nick fled into deep hiding.

Then Davey drops the real twist. Years ago he paid Holly and Nick in Bitcoin for an amphetamine deal, but he never handed over the real wallet.

Instead he gave them a fake string of numbers on paper—a worthless key. He kept the genuine Bitcoin, slowly cashing it out for himself as its value soared, while Holly and Nick believed they were sitting on a fortune.

Their recent plan to cash out was the moment he knew he’d be exposed. Holly’s attempt on Nick was sparked by desperation and greed, but the treasure she fought over didn’t exist.

The paper the club recovered from the safe is worthless.

While this revelation sinks in, Ron hides in Pauline’s flat, certain someone is following him. Danny breaks in, gun drawn, demanding the Bitcoin paper.

He says Connie tipped him off and hired him to kill Ron. Ron bargains for his family’s safety, forcing Danny to call the hitman and cancel both murders.

As Danny finishes the call, armed police storm in. Connie has worked with Ron and the authorities to trap him.

Danny is arrested, and Suzi, Jason, and Kendrick are safe.

In the aftermath Ron and Ibrahim repair their friendship and talk about Connie’s uneasy role in saving them. Lord Townes, financially wrecked and clinging to the dream of a commission, takes a boat into the Channel with a gun and disappears, leaving police to suspect him in Holly’s death.

Weeks pass. Nick remains missing.

Joyce concludes that Holly destroyed herself for a fortune that was never there.

Later, Paul learns from solicitor Jeremy Jenkins that sealed envelopes with the two codes still exist. Joanna admits she withheld this, fearful Paul might be involved, but they choose honesty and stay together.

Finally, Nick is revealed hiding in a cheap Travelodge, living off vending machines and fear. A radio dedication from Paul convinces him to call on a burner phone.

Paul tells him it’s safe, that Holly is dead, and that there is good news and bad news—setting the stage for whatever comes next.

Characters

Joyce

Joyce comes through as the emotional anchor and the most openly human lens on events in The Impossible Fortune. She is warm, chatty, and deeply domestic in her instincts, which makes her both relatable and occasionally blinkered.

Her narration style leans toward small details—cake prices, hats, nail bars, music choices—yet those details quietly reveal her values: she wants safety, tradition, and a sense that life is held together by ritual. The wedding planning shows how much she loves Joanna, but also how love turns to control when Joyce feels her role slipping; she fights about hymns, guest counts, and the “older bride” comment not because she is cruel, but because she is anxious and trying to protect the story she carries of family and loss.

At the same time, Joyce is no fool. She can be stubbornly certain of her instincts—her quick suspicion of Davey Noakes is a good example—but her certainty is often a cover for fear that she might not understand this new world of cryptocurrency, cold-storage facilities, and professional bombs.

In the investigation she plays a subtle but vital part: not the mastermind, but the conscience and texture of the group, the one who keeps people tethered to ordinary life even while stepping into danger.

Elizabeth

Elizabeth is the strategist, the cold-eyed realist, and the gravitational center of the Thursday Murder Club dynamic in The Impossible Fortune. Her grief for Stephen gives her a quieter vulnerability than she usually allows to surface; she is restless with the idea of “ordinary life,” and this case becomes a way to keep moving when stillness feels unbearable.

She is relentlessly analytical, always widening the suspect pool, always refusing obvious stories, and her instincts about people are razor sharp—she reads Nick’s fear, Townes’s performance, and even the convenience of the whole setup with suspicion. Yet her brilliance is paired with a quietly protective streak: she limits police involvement to Donna, she brings Joyce along partly for companionship and partly as a safeguard, and she treats danger as a shared burden rather than a personal thrill.

Elizabeth’s moral compass is complicated; she will bend rules, trespass, and manipulate a scene if it helps her reach truth or protect her circle. What makes her compelling is that her competence never hardens into cruelty—her empathy is simply disciplined, expressed through action rather than comfort.

Ron Ritchie

Ron is defined by loyalty, bruised idealism, and a body that carries the history of violence he has survived. In The Impossible Fortune his hangover scenes are comic on the surface, but they expose the way trauma lives in him: the memory of police brutality on a picket line is not a story he tells for pity, it is a scar that still shapes his reflexes.

He is physically tough but emotionally raw where family is concerned, especially Suzi and Kendrick. His suspicion about Nick’s story shows the part of Ron that distrusts easy narratives and resents being played; he is the skeptic who keeps the club from becoming romantic about their own cleverness.

Family pressure pulls him away from the case and forces him into a more personal battlefield, where his courage changes shape. His confrontation with Danny is Ron at his most dangerous and most loving—he negotiates with a violent man not for pride but to save his daughter and grandson.

Even when he hides plans from the group, it comes from a protector’s instinct, not ego. Ron’s arc sits at the junction of private tenderness and public hardness, showing how a man can be both gruff and profoundly devoted.

Ibrahim Arif

Ibrahim is the moral steadying hand in The Impossible Fortune, and his calm has weight because it is chosen, not naive. He is compassionate but not sentimental; he tends to Ron’s hangover with care, mentors Connie into something constructive, and listens to Joanna’s doubts without theatrics.

His advice to Joanna is classic Ibrahim: he doesn’t tell her what to do, he reflects her own truth back to her. He values responsibility and repair, which is why he pushes Connie toward mentoring and away from small-time crime, even if that choice brings friction with Ron.

Ibrahim also represents the club’s quiet faith in people: he believes in growth, in second chances, and in the possibility that even dangerous lives can bend toward good. Yet he is not blind to risk; his willingness to access old contacts and think about the cold-storage codes shows a practical edge beneath the gentleness.

In many ways he is the club’s conscience, but a conscience that still understands the messy, compromised routes truth sometimes requires.

Joanna

Joanna embodies modernity pressing against grief and tradition in The Impossible Fortune. She is decisive, witty, and allergic to being infantilized, which is why she clashes with Joyce so sharply.

Her wedding preferences—no hymns, Backstreet Boys, “small” but still huge by normal standards—show her desire to own her narrative rather than inherit one. Beneath her confidence sits real vulnerability: marrying Paul after six months frightens her, and she seeks reassurance not from peers but from Ibrahim, a choice that reveals how deeply she trusts older wisdom even while resisting older rules.

Joanna is also emotionally mature in conflict; when Paul’s history with Holly surfaces, she pressures honesty but rejects melodrama, offering compassion for complicated feelings rather than demanding a clean script. Her arc suggests a woman learning how to hold love and doubt together without breaking either.

Paul

Paul in The Impossible Fortune is kind, slightly bewildered by the storm around him, and defined by loyalty that sometimes drifts into avoidance. Joyce’s affection for him is earned: he is gentle with Joanna and respectful to her family, and he has the decency to feel guilty when his grief for Holly does not match expectations.

His past relationship with Holly complicates the case, but his confession to Joanna suggests he is not a liar by nature; he is more a conflict-avoider who learns, through marriage and crisis, that truth up front is safer than truth dragged out. As an early investor and friend to Nick, he sits at a fault line between personal trust and financial risk.

What makes Paul interesting is that he is not a noir-style suspect or a hero, just an ordinary man forced to discover whether he can stay ordinary while the people around him become lethal.

Nick Silver

Nick is a study in charm layered over fear in The Impossible Fortune. He comes across as confident enough to run a high-stakes cold-storage business and to stroll out of trees at a wedding to reveal a bomb plot, yet every move he makes telegraphs panic and calculation.

His request for Elizabeth’s discreet help rather than police involvement is both logical and suspicious, capturing how Nick lives at the edge of legality even if he doesn’t see himself as “criminal. ” His relationship with Holly is built on mutual secrecy and mutual necessity, which becomes fatal once greed and paranoia take over.

When he disappears, he turns into a ghost like the fortune itself—both central and unreachable. His eventual hiding in a Travelodge for weeks paints him as less a mastermind and more a terrified survivor, a man who believes he’s clever enough to outwait danger even while the world collapses around him.

Nick’s defining trait is self-preservation, and the tragedy is that his survival instinct is what makes him both victim and catalyst.

Holly Lewis

Holly is the sharpest example of ambition curdling into recklessness in The Impossible Fortune. She is presented at first as an equal partner to Nick—brilliant enough to build a fortune, disciplined enough to split access codes, and careful enough to store failsafes with solicitors.

But the truth cracks open a darker edge: she is willing to kill Nick for complete control, and her plan is not heat-of-the-moment desperation but cold, premeditated greed. Her anger at Paul and refusal to attend the wedding reveal a personal emotional volatility that mirrors her professional one; she does not tolerate being sidelined, whether in love or money.

Her death by car bomb is grimly ironic, the violent consequence of the violent tactics she embraced. Even in absence she shapes the story: her secrets, phone calls, and ruthless gamble set every other character spinning.

Davey Noakes

Davey is danger wrapped in professionalism in The Impossible Fortune, a man with a criminal past who now operates in the sleek, shadowy world of illegal tech. He is intimidating, but not chaotic; his demeanor is controlled, and his home confrontation scene shows how carefully he manages power dynamics.

Davey’s revelation about the fake Bitcoin wallet reframes him as both conman and long-game survivor—he outfoxed Holly and Nick years ago, then spent years drifting under the weight of his own deception. His role in returning the bomb to Holly is morally tangled: he claims he wanted to scare, not kill, yet he chose a method that any experienced criminal would know could spiral.

Davey is neither pure villain nor repentant sage; he is a pragmatist who misjudged the size of the fire he was playing with. His honesty now is less about redemption and more about control—he wants the narrative in his hands before others write it for him.

Lord Robert Townes

Lord Townes in The Impossible Fortune represents decaying privilege and the terror of becoming irrelevant. His estate is grand but rotting, mirroring a man whose title no longer provides meaning or security.

He performs warmth and surprise when confronted about Holly’s death, but the façade is thin; Joyce senses his knowledge immediately, and Elizabeth reads him as a man who has rehearsed his innocence. His motivation is painfully human despite the aristocratic shell: he is broke, purposeless, and seduced by the idea that one final deal could restore control.

The family motto “Kill or be killed” is not just heritage but a psychological permission slip, pushing him toward decisive, potentially violent action for the first time in his drifting life. His disappearance by boat and near-suicide sketch a man who believed money would save him, then found himself staring at the void when it didn’t.

Townes is tragic because he is hollowed out by entitlement and fear, yet still capable of self-awareness too late to change course cleanly.

Connie Johnson

Connie is the embodiment of hard-earned intelligence in The Impossible Fortune, a woman shaped by crime but not reduced to it. Fresh from a mistrial, she carries bitterness and a hunger for agency, yet Ibrahim’s push toward mentoring reveals another side: she likes power, but she also likes teaching, shaping, and leaving a mark that isn’t destruction.

Her meeting with Tia shows Connie as a coach who forces ambition upward; she refuses small thinking and reorients Tia toward a bigger, riskier, more organized heist. That guidance is morally dark but psychologically nuanced—Connie is trying to create professionalism and loyalty in a world she knows will chew amateurs apart.

Later, her involvement in the Danny trap reveals her as strategic and unexpectedly cooperative with law enforcement when it suits a larger plan. Connie’s complexity comes from the way she mixes predator instincts with a mentor’s pride; she wants to win, but she also wants her protégés to be worthy of winning.

Tia Malone

Tia is youthful hunger colliding with conscience in The Impossible Fortune. She wants money and status, and her criminal trajectory—from snatching Rolexes to planning warehouse robberies—shows a mind that escalates quickly once it believes in its own capability.

Yet she is not numb to what she’s doing. In the warehouse scene, her reflections on low wages, systemic weakness, and the temptation of legitimate life reveal a conscience that hasn’t been burned out yet.

She steels herself to point guns at ordinary workers, but the fact that she has to steel herself matters; she is still negotiating with her own moral boundary. Her relationship with Connie is almost parental in structure—Tia seeks approval and direction, and Connie offers ambition as a replacement for fear.

Tia stands at a crossroads between becoming a hardened criminal or a clever survivor who exits in time, and the tension of that choice hums beneath her every action.

Danny Lloyd

Danny is the clearest portrait of coercive violence in The Impossible Fortune. He is a controlling abuser who masks cruelty with casual dismissal, treating Suzi’s pain as inconvenience and assuming every rebellion is temporary theater.

His internal monologue reveals entitlement at its ugliest: he imagines leaving for a pub, returning to reassert dominance, and later arranging murders with the cold logic of a businessman. Danny is not impulsive; he is systematic, which makes him more frightening.

The moment Suzi turns the tables, his mind immediately shifts to revenge fantasies rather than remorse, proving that his identity is built on power, not love. Even when forced to call off the hits, he does so through negotiation with Ron, not moral reckoning.

Danny functions as a human toxin in the story, a threat that exposes how personal violence can be as lethal and strategic as any bomb.

Suzi Lloyd

Suzi’s arc in The Impossible Fortune is one of reclaimed agency. She begins as a woman who has learned to compartmentalize—smiling in public, enduring in private—but the confrontation scene shows her stepping into clarity with frightening calm.

She is not acting from chaos; she has planned Danny’s exit, packed his suitcase, timed Jason’s arrival, and anchored her threat in the protection of Kendrick. Her threat is not cruelty, but a boundary drawn in steel: she will not be victim again.

What makes Suzi powerful is her emotional realism; she knows the danger of Danny returning, knows the cost Jason might pay if he protects her, and chooses a path that saves both. In a novel full of murder mysteries, Suzi represents another kind of survival story, one where courage is domestic, intimate, and absolute.

Kendrick

Kendrick in The Impossible Fortune provides a clear-eyed innocence that cuts through adult nonsense. He is calm, literal, and perceptive, and his brief lines about possibly being neurodivergent are not a label for drama but a way to explain his processing of fear.

He notices the gun, his mother’s swollen eye, and the emotional temperature of the room with blunt accuracy. His acceptance of Danny leaving is heartbreaking and illuminating: he trusts Suzi’s promise because she finally speaks with certainty.

Kendrick’s presence raises the stakes for Ron and Suzi and reframes the conflict not as marital drama but as generational safety. He is the moral center of that subplot, the child whose quiet resilience makes the adults’ actions feel necessary rather than abstract.

Jason Ritchie

Jason acts as the protective fuse in The Impossible Fortune—rarely on stage, but always close to ignition. He is the brother Suzi relies on and the threat Danny fears, which positions him as a symbol of familial defense.

Jason’s arrival after Suzi’s selfie shows him as someone who responds, not hesitates. Even when he and Kendrick protect Ron from the full truth, it reads as loyalty rather than deception.

He becomes a target for Danny’s planned killings simply because Danny understands Jason as a credible counterforce. Jason’s role is less about investigation and more about representing the line between abuser and consequence.

Donna De Freitas

Donna is the bridge between official law enforcement and the Thursday Murder Club in The Impossible Fortune. She is sharp, ambitious, and increasingly confident in challenging Elizabeth, which signals her growth from sidekick to near-equal.

Her irritation at royal-visit duty and her teasing rapport with colleagues make her feel real rather than procedural. Donna’s investigative leap about the Manchester number—realizing Jamie Usher might be the true contact—shows her as a detective who can outthink the amateurs when she focuses.

She also has a moral spine; she demands clarity about bombs and codes, refuses to be excluded, and maintains professional skepticism even while being emotionally fond of the club. Donna is the novel’s reminder that institutional competence exists, even if it often needs the club’s chaos to spark it.

Detective Chris Hudson

Chris provides a comic, self-mocking contrast in The Impossible Fortune, but his humor hides insecurity. He brags about solving cases without elderly interference, yet the need to say it so loudly suggests he misses the friction and brilliance the club brings.

His anecdote about Johnny Jacks shows a detective who trusts his instincts and enjoys theatrically proving himself right. The firearms-training joke underscores his self-awareness; he knows he isn’t a swaggering action hero, and he leans into that.

Chris is a good policeman with a slightly bruised ego, and his presence keeps the official investigation from feeling like a faceless machine.

DCI Varma

Varma appears as the weary professional drowning in a case designed to resist normal policing in The Impossible Fortune. The encrypted emails, missing phone, and unhelpful forensics leave Varma in a fog, and his frustration highlights how the case sits outside standard patterns.

He becomes a narrative counterweight to the club’s improvisational methods—what they can intuit socially, he cannot extract scientifically. Varma is competent, but the world of cryptocurrency, private cold storage, and bespoke bombs makes competence feel inadequate.

Bogdan

Bogdan is the club’s quiet muscle and discreet ally in The Impossible Fortune. He forces entry into Nick’s office without fanfare, signalling disciplined capability rather than brute theatrics.

His synchronized lie with Ron about bowling shows loyalty to the club’s secrecy, even when it risks his standing. Bogdan’s personality is defined by calm presence and selective involvement—he doesn’t dominate scenes, but when he appears, things get done.

Carlito

Carlito, the minibus driver, adds a grounded slice of ordinary community life to The Impossible Fortune. His role is small but symbolic: he is one of the everyday people orbiting Coopers Chase, enabling the club’s movements without being swallowed into the chaos.

His cheerful greeting to Elizabeth suggests she is a known figure even outside the club, reinforcing her social reach.

Pauline

Pauline functions as Ron’s domestic counterpoint in The Impossible Fortune. She feeds, cares, and provides a place of refuge, embodying the small kindnesses that keep battered people upright.

Her flat becomes the stage for Ron’s standoff with Danny, turning her ordinary home into a site where safety is defended. Pauline is not a detective, but her quiet steadiness makes the detectives possible.

Archie

Archie is a light romantic flicker in The Impossible Fortune, noted through Joyce’s amused observation that he seems interested in Elizabeth. His presence gently suggests that Elizabeth’s life still contains possibility beyond grief and mystery, even if she barely allows herself to notice it.

Jill Usher

Jill is a ghostly name at first in The Impossible Fortune, representing the “Manchester link” and the way innocence can be used as camouflage. The detail that the contract is in her name frames her as potentially unaware, more a vessel for someone else’s scheme than an active conspirator.

She stands for how crime often launders itself through ordinary identities.

Jamie Usher

Jamie emerges as the more plausible criminal connective tissue in The Impossible Fortune. His history of fraud and the suspicion that he used Jill’s name suggest a man comfortable with deception as infrastructure.

Even without a full arc in the summary, he represents the mid-level predator who thrives in financial shadows and becomes a key lead because Donna understands motive, not just paperwork.

Jeremy Jenkins

Jeremy is the anxious custodian of secrets in The Impossible Fortune. He is an ordinary solicitor suddenly holding sealed envelopes that might unlock a fortune, and his fascination mixed with professional restraint paints him as a man tempted by drama but ruled by duty.

His role shows how even mundane bureaucratic positions can sit at the hinge of extraordinary events, and his careful procedure contrasts with the recklessness of everyone chasing the codes.

Unnamed narrator linked to “Boom or Bust”

The unnamed voice at the start of The Impossible Fortune sets the moral temperature for the plot: cold, transactional, and terrifyingly casual about murder. Their cost-per-life calculation and outsourcing of the bomb show a worldview where human beings become line items.

Even without later identity revealed in the summary, this narrator embodies the modernized violence of the story’s world—crime as service industry, death as purchasable convenience. This figure functions less as a full character so far and more as a lurking threat, a reminder that the novel’s dangers are industrialized and anonymous.

Gerry

Gerry, Joanna’s late father, is absent in body but emotionally central in The Impossible Fortune. The wedding arguments and reconciliation hinge on his memory, and Joanna’s choice to have Joyce walk her down the aisle is explicitly a way to keep Gerry present.

He symbolizes the tenderness beneath family conflict and the shared grief that softens Joyce and Joanna back toward each other.

Stephen

Stephen, Elizabeth’s late husband, shapes her interior landscape in The Impossible Fortune. Her moments alone at the wedding terrace show a woman unsure how to return to normal life after losing her partner.

Stephen’s absence is what makes Elizabeth’s appetite for mystery feel less like hobby and more like survival; investigation becomes movement, movement becomes coping.

Pete Tong

Pete Tong appears only as a cultural echo in The Impossible Fortune, but his presence matters for Nick’s final reveal. Listening to him in hiding emphasizes Nick’s isolation and the strange normality he clings to.

The dedication Paul makes on air becomes the thin thread that pulls Nick back into the world, so Pete Tong functions as an accidental catalyst for the next stage of the story.

Hassan, Benny, and Bobby

These three sit on the edges of the heist plot in The Impossible Fortune, but each reflects a different face of ordinary labor caught in criminal currents. Hassan, the forklift driver, is pulled into Tia’s plan as an inside lever, suggesting a worker whose vulnerabilities or resentments make him recruitable.

Benny and Bobby are the chatting guards whose banter and underpayment signal how fragile security becomes when systems rely on exhausted people. They are not deeply individualized in the summary, yet collectively they show the social ecosystem crime exploits.

Themes

Greed, Illusion, and the Price of Wanting More

Money in The Impossible Fortune is never just a resource; it is a mirror that shows what people are willing to become. The storyline around the supposed Bitcoin fortune exposes how greed can hollow out judgment and warp relationships.

Holly and Nick live for years believing they possess a key to unimaginable wealth, and that belief shapes their identities, careers, and sense of safety. When the imagined fortune becomes threatened, the response is not cautious protection but escalation into betrayal and murder.

Holly’s choice to try to kill her partner for a code illustrates greed’s most corrosive form: the belief that another human life is simply an obstacle between you and what you feel you deserve. Importantly, the twist that the fortune was never real turns greed into tragedy and dark comedy at once.

The characters are not destroyed by actual money, but by the fantasy of it. Their fear, violence, and paranoia are built atop nothing.

Davey Noakes represents another shade of greed: pragmatic, patient, and quietly predatory. He does not need violence to take what he wants; he uses time and deception, letting others dream while he profits.

His decision to hand over fake wallet codes years ago is a long con rooted in the assumption that everyone can be managed if you control their hope. Even Lord Townes, who dresses his motives in respectability, is compromised by the lure of commission and the chance to restore status.

The phrase “Kill or be killed” hanging over his reflections shows how greed disguises itself as necessity when pride is involved.

By letting the “fortune” evaporate, the novel argues that greed is self-generating: it does not require a real prize. The chase is enough to make people cruel.

The result is a world where value is measured not in pounds or coins, but in what someone is willing to sacrifice—trust, dignity, even life—for the feeling of being one step from riches.

Violence as a Continuum: From Public Terror to Private Control

The story places two kinds of violence side by side: spectacular violence meant to shock the world, and quiet violence meant to rule a household. The opening voice discussing bomb procurement is chilling precisely because it treats murder as a transaction.

The narrator calculates cost per life, chooses a “small-to-medium” device for convenience, and uses a customer-service style criminal marketplace. This frames terror not as chaotic rage but as consumer logic: violence outsourced, branded, delivered.

It reflects a society where cruelty can be efficient, distant, even bureaucratic. Killing becomes easier when responsibility is broken into steps and sold as a service.

Against this sits Danny Lloyd’s domestic abuse, which is not efficient at all, but grinding and intimate. Suzi’s confrontation reveals years of psychological erosion—the forced smiles, the routine fear, the sense of being trapped inside someone else’s mood.

Danny’s casual instruction that she should “smile more” is a small sentence loaded with power; it shows how abusers normalize harm and expect the victim to manage appearances. The gun scene flips that script.

Suzi uses Danny’s own weapon not to become violent herself, but to interrupt the structure of control. Her warning about Jason arriving, and her willingness to protect Jason from becoming a killer, underline the moral cost abuse spreads through families.

Harm does not stay between two people; it radiates.

These two strands make one point together: violence is not only about bodies. It is about domination.

Whether it is a bomb under a car or a threat whispered in a kitchen, the intention is to decide who gets to live freely and who must live in fear. The novel quietly insists that private violence is as politically meaningful as public violence.

Both rely on systems that allow harm—criminal networks, weak security, social silence, and the tendency of others to look away until someone insists on being seen.

Trust, Betrayal, and the Fragility of Chosen Families

At the heart of the book is a contrast between relationships built on loyalty and relationships built on utility. The Thursday Murder Club’s circle functions like a chosen family: they argue, tease, and doubt each other, but their default setting is care.

Joyce’s letters and diary entries show affection in ordinary gestures—dancing at a wedding, shared breakfasts, rides in minibuses, even buying flapjacks when time is short. These moments matter because they establish trust as a daily practice, not a dramatic promise.

When Elizabeth asks Joyce to come with her into danger, it is not because Joyce is useful in a tactical sense; it is because companionship steadies the mind. The group’s warmth does not erase suspicion, but it gives suspicion a humane boundary.

In contrast, Nick and Holly’s partnership has been corroded by secrecy. Their split codes and solicitor-held envelopes were supposed to protect them, yet the very structure implies that each sees the other as a possible threat.

This kind of trust is contractual and fragile. Once pressure arrives, betrayal becomes thinkable, and then inevitable.

Holly’s attempt on Nick’s life is not a sudden moral collapse; it is the endpoint of a relationship already organized around withholding.

Ron’s storyline adds another layer. He resists working with Connie because of past wounds and principles, yet he ultimately depends on her to safeguard his family.

Trust here is negotiated under stress, revealing that loyalty is complicated and sometimes uncomfortable. The choice to accept help from someone you dislike can be a form of love, because protecting others matters more than preserving old grudges.

Even Ibrahim’s forgiveness of Ron shows trust as renewal rather than naïve faith.

The novel suggests that betrayal is rarely about one moment of treachery. It grows in spaces where people stop seeing each other as ends in themselves.

Trust survives where people remain willing to be vulnerable, to forgive, and to prioritize human bonds over advantage. The contrast between the Murder Club’s affectionate messiness and the cold calculus around the Bitcoin codes makes that argument without ever preaching it.

Aging, Grief, and the Search for Meaning After Loss

Grief in The Impossible Fortune is not treated as a single event but as a long afterlife that reshapes identity. Elizabeth’s quiet moment at Joanna’s wedding, sitting alone as sunlight fades, shows how loss lingers even in rooms full of celebration.

Her husband Stephen is absent not only as a person but as a structure of meaning. She wonders how to return to ordinary life, hinting that grief demands a new version of the self.

Yet she does not retreat. Instead, she keeps moving—into mysteries, into danger, into responsibility for others.

The investigation becomes a way to stay engaged with life when the old reasons have disappeared.

Joyce’s reflections on Gerry operate differently. Her grief is woven into family rituals and memory.

The wedding planning conflict with Joanna is charged because both mother and daughter are negotiating how to honor a dead father without letting his absence dominate their future. Joanna asking Joyce to walk her down the aisle is a tender compromise: she cannot have Gerry there, but she can carry his presence through the act of choosing who represents him.

That moment shows grief as something families continually translate into new forms.

Ron’s hangover memory of being beaten during a picket line brings aging into focus. The body remembers violence and fatigue, while the mind keeps score of history.

His worry about Suzi and Kendrick is also the worry of a man who knows time is finite and that protection must happen now, not later. Aging here is not about decline alone; it is about sharpening priorities.

The older characters are not idle background figures. Their experiences make them quick to notice patterns of human behavior—greed, fear, love—because they have survived them before.

Through these arcs, the novel frames meaning as something you keep rebuilding. Loss is permanent, but so is the possibility of purpose.

The elderly detectives pursue truth not because they are bored, but because the act of caring, solving, and safeguarding each other is a form of staying alive in the deepest sense. Grief does not end; it changes shape, and people either shrink under it or learn to live alongside it.