The Librarian of Burned Books Summary, Characters and Themes

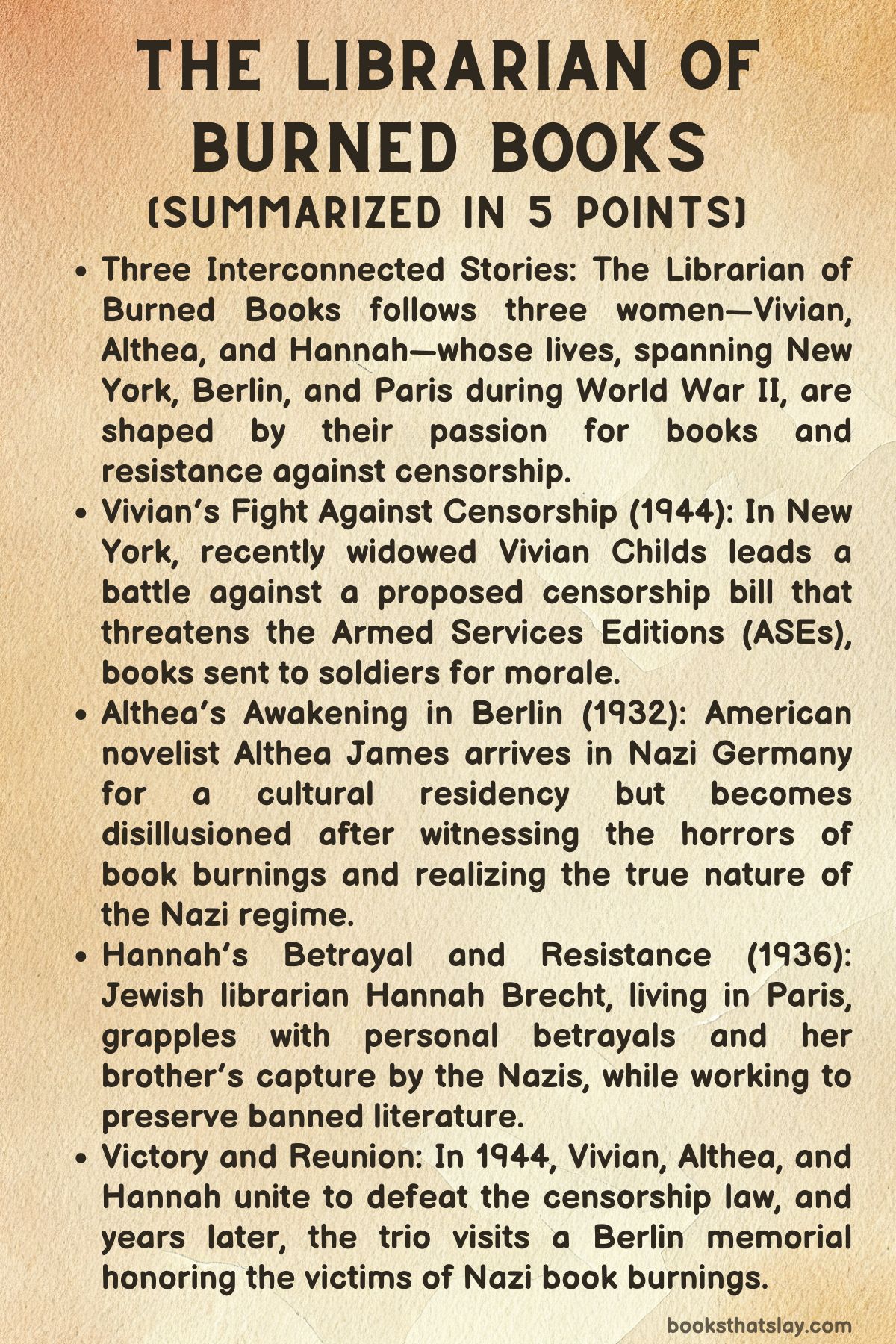

The Librarian of Burned Books by Brianna Labuskes is a compelling historical novel that intertwines the stories of three remarkable women across different countries and moments in history, bound by their shared passion for books and their defiance against censorship.

Set against the backdrop of Nazi Germany, pre-war Paris, and wartime America, the novel explores themes of loss, resistance, betrayal, and redemption. As the characters face the horrors of World War II, they find themselves drawn into dangerous political movements, personal betrayals, and courageous acts of resistance, all while battling for the freedom of expression and the preservation of literature.

Summary

The novel opens in New York in 1944, where Viv Childs is grappling with the loss of her husband in the war. In the midst of her grief, she is thrown into another fight—this time against a proposed censorship law that threatens her work with Armed Services Editions (ASEs), the small paperback books distributed to soldiers as morale boosters.

Determined to prevent this, Viv begins planning a large-scale event to rally public support and discredit Senator Taft, the bill’s primary advocate.

As part of her strategy, she seeks out two key figures: a reclusive author named Althea James and a mysterious librarian who has made it her mission to protect books once destroyed in Nazi book burnings.

Flashback to Berlin in 1932, where American author Althea James arrives in the city as a guest of the Nazi Party, which seeks to cultivate cultural connections with America.

At first, Althea is swept away by the glamour and intellectual energy of Berlin, forming a close friendship with two women—Deveraux Charles, a lively actress and screenwriter, and Hannah Brecht, a Jewish woman who works in a library that preserves banned literature.

However, Althea’s world shatters when she witnesses a brutal book-burning ceremony orchestrated by the Nazis.

Deeply shaken, Althea becomes aware of the true extent of the regime’s cruelty, particularly after discovering that Hannah’s brother, Adam, is part of a covert resistance movement.

Althea and Hannah’s friendship deepens, and they become lovers. However, their relationship is torn apart when Diedrich, Althea’s Nazi liaison, uncovers the affair. In retaliation, Diedrich orchestrates Adam’s capture and implicates Althea, leading Hannah to sever ties with her.

Several years later, Hannah, now in Paris, organizes exhibitions against Nazi oppression, but her life is still marked by the trauma of her brother’s betrayal and the suspicion that Deveraux, her old friend, had a role in it.

When Hannah confronts Deveraux, she learns that Deveraux had indeed given up Adam to maintain her Nazi connections, but only after receiving information from Otto, another friend of Hannah’s. Devastated by the betrayals, Hannah breaks off all ties with Otto and leaves for America.

Back in 1944, Viv manages to convince Althea to emerge from her secluded life and speak at her anti-censorship event.

At the same time, she discovers that the mysterious librarian safeguarding the burned books is none other than Hannah Brecht. Together, the women give stirring speeches about their experiences in Nazi Germany, with Althea reflecting on the horrors she witnessed and Hannah calling attention to the destruction of intellectual freedom.

Their powerful testimonies sway public opinion, leading to the defeat of the censorship law.

In the novel’s conclusion, Viv rekindles a relationship with Hale, her late husband’s half-brother, and years later, the three women travel to Berlin to visit a memorial honoring the victims of the infamous book burnings.

Characters

Vivian Childs

Vivian is a determined and resilient woman who, despite the personal loss of her husband in World War II, channels her grief into a fight against censorship. Her work with the Armed Services Editions (ASEs) demonstrates her belief in the power of literature, particularly in maintaining morale among soldiers on the front lines.

Her character embodies the struggle for freedom of expression during wartime, and her opposition to Senator Taft’s censorship proposal highlights the tension between patriotism and intellectual freedom on the home front. Vivian’s personal journey intertwines with her professional mission, and as she rekindles her relationship with Hale, the story hints at her desire for personal healing and moving forward after tragedy.

Her strategic approach in organizing the event against censorship shows her ability to rally others for a greater cause. She blends her personal passion for books with her civic responsibility.

Althea James

Althea is portrayed as a complex character who is shaped by her deep love for literature and her subsequent disillusionment with the Nazi regime. Initially, she is drawn to Berlin’s cultural scene, seeing her residency as an opportunity to contribute to German-American relations through art and literature.

However, her experiences in Nazi Germany, particularly witnessing the horrific book burnings, shatter her naive understanding of the regime. Althea’s involvement with Hannah and the resistance movement places her at odds with Diedrich and the Nazi apparatus.

The betrayal she experiences from Diedrich and the resulting fallout with Hannah marks a pivotal point in her life, as she is left ostracized and guilt-ridden. Her reclusive nature by 1944 reflects her unresolved trauma and sense of shame, but her decision to join Vivian’s cause is an act of redemption.

Althea’s character arc, from an optimistic novelist to a scarred survivor, underscores the personal cost of standing against tyranny. The novel highlights the power of literature as both a refuge and a weapon in times of political oppression.

Hannah Brecht

Hannah is a German Jewish woman whose life is profoundly affected by the rise of the Nazi regime and the loss of her brother, Adam. As a librarian who champions banned books, she is committed to preserving the intellectual heritage that the Nazis seek to destroy.

Her relationship with Althea in Berlin adds an emotional layer to her resistance, but it is fraught with the dangers of betrayal and political intrigue. Hannah’s grief over Adam’s capture and death, compounded by her discovery that both Otto and Deveraux played roles in his downfall, drives her to distance herself from the people she once trusted.

Her relocation to Paris and subsequent work in America suggest that she is trying to rebuild her life, though the pain of the past lingers. When she resurfaces in 1944 as the mysterious librarian at Viv’s event, her rousing speech about the intellectual fall of Germany positions her as a moral compass in the novel.

Hannah represents the importance of memory and resistance against authoritarianism. Her reunion with Althea indicates a possible healing of old wounds, but also a recognition of their shared trauma.

Diedrich

Diedrich is initially depicted as a charming and sophisticated figure who helps Althea navigate her new life in Berlin. His loyalty to the Nazi regime reveals a much darker side.

His sense of betrayal when Althea turns against the Nazis leads to his vindictive actions, including arranging Adam’s capture and implicating Althea. Diedrich’s character embodies the seductive allure of fascism, offering the appearance of refinement and culture while masking the brutality of the regime.

His manipulation of both Althea and Hannah reflects the personal and political betrayals that are central to the novel’s exploration of trust and loyalty in dangerous times.

Deveraux Charles

Deveraux is a complex figure whose motivations are ambiguous throughout much of the story. As a glamorous actress and screenwriter, she seems at home in the glittering world of Berlin’s cultural elite, but her complicity with the Nazis, revealed through her betrayal of Adam, casts her in a morally dubious light.

Her justification that she was spying on the Nazis in an effort to subvert them adds a layer of complexity to her character. It is unclear whether she truly believed she was doing the right thing or if she was more concerned with self-preservation.

Deveraux’s betrayal of both Adam and, indirectly, Hannah, positions her as a tragic figure. Her personal ambition leads her to compromise her morals, ultimately costing her the trust of her closest friends.

Otto

Otto is Hannah’s childhood friend who becomes increasingly consumed by his hatred of the Nazis. Though initially portrayed as a reliable and close companion to Hannah, it is later revealed that Otto played a role in Adam’s capture by selling information on his plans.

This betrayal cuts deeply for Hannah, who views it as a personal violation as well as a political one. Otto’s descent into instability reflects the broader theme of how individuals react to the trauma of living under a repressive regime—some, like Hannah, choose resistance, while others, like Otto, become lost in their own rage.

His betrayal serves as a key turning point in the novel, forcing Hannah to confront the consequences of misplaced trust.

Hale

Hale is Vivian’s first love and the half-brother of her deceased husband, which adds a layer of emotional complexity to their relationship. As Vivian works to organize the event against censorship, Hale becomes her confidant and partner, offering support both emotionally and strategically.

Their relationship, which is rekindled after the war, symbolizes hope and the possibility of finding solace and companionship even in the aftermath of loss. Hale’s character is not explored as deeply as the other figures in the novel, but his presence is important in anchoring Vivian’s personal storyline.

He offers her a chance at happiness and emotional recovery as she moves forward from the grief of her husband’s death.

Adam Brecht

Although Adam does not appear directly in much of the novel, his presence looms large over the narrative, particularly for Hannah. As a member of the resistance movement, Adam’s capture and death at the hands of the Nazis is a turning point for several characters, particularly Hannah, Althea, and Deveraux.

His role in the resistance movement and subsequent martyrdom make him a symbol of the intellectual and moral fight against fascism. His loss is felt deeply by his sister, who carries the weight of his memory throughout the story.

Adam’s character, though not explored in detail, represents the stakes of the resistance. He symbolizes the personal sacrifices made by those who opposed the Nazi regime.

Themes

The Intersection of Censorship, Intellectual Freedom, and the Fight for Cultural Preservation

One of the central themes of The Librarian of Burned Books is the intricate relationship between censorship, intellectual freedom, and the fight to preserve culture during times of war and political upheaval. The novel examines how censorship is wielded as a tool of control by authoritarian regimes, particularly the Nazis, who destroy books as symbols of dangerous ideas and dissent.

This is vividly captured in the scene where Althea and Hannah witness the burning of thousands of books in Berlin—a violent attack on both physical texts and the collective memory they represent. The act of burning books becomes a metaphor for the erasure of culture, ideas, and identities that threaten the power structure.

Althea, a novelist whose life revolves around storytelling and knowledge, is devastated by this destruction, which catalyzes her rejection of the Nazis. In 1944 New York, Viv’s battle against the censorship of Armed Services Editions highlights a different form of suppression, rooted in political conservatism and the desire to limit soldiers’ access to diverse ideas.

The ASEs, which are meant to boost morale and maintain intellectual engagement among troops, represent a beacon of free thought. Viv’s efforts to preserve them underscore the ongoing struggle to protect intellectual freedom from political interference, regardless of the context.

Betrayal, Moral Ambiguity, and the Complexity of Resistance

Throughout the novel, betrayal is a crucial theme, intersecting with moral ambiguity and the perilous decisions people make during times of extreme oppression. Characters like Deveraux and Otto exemplify the blurred lines between right and wrong when individuals are forced into morally compromising situations.

Deveraux’s betrayal of Adam is initially framed as a self-serving act, but her complex motives as a spy trying to subvert the regime are revealed later. Otto’s betrayal of Adam, driven by his growing hatred of the Nazis, complicates the reader’s understanding of resistance and collaboration, showing how even those who resist can become corrupted by their own obsessions.

Betrayal also plays out on a personal level in the relationship between Althea and Hannah. Althea’s perceived betrayal by Diedrich leads to Adam’s capture and creates a deep rift between the two women, demonstrating how love and loyalty are tested in times of war.

The novel suggests that resistance is not a straightforward moral path but rather a labyrinth of difficult choices, where betrayal and sacrifice often intersect.

The Personal and Collective Trauma of War and Displacement

The theme of personal and collective trauma is explored through the experiences of the three protagonists, each marked by dislocation and loss due to World War II. Althea, who witnesses the devastation of Nazi Germany’s cultural policies firsthand, is scarred by the book burnings and the betrayal she experiences, leading her to a life of reclusion.

Hannah’s trauma is even more pronounced, as she deals with the destruction of her family, her brother’s capture, and the betrayal by close friends. Her decision to flee to Paris and later to America reflects the emotional and physical displacement faced by many Jewish refugees during the war.

Collective trauma is also evident in Viv’s storyline as she mourns the loss of her husband while fighting to preserve intellectual freedoms under attack on the home front. The women’s journeys symbolize the broader suffering of their nations, highlighting the lingering impact of war on individual psyches and collective memory.

In the novel’s final scenes, when the elderly women return to Berlin to witness the memorial to the book burnings, it serves as a poignant moment of reconciliation and a recognition of the need to commemorate cultural loss.

The Role of Women in the Preservation of Cultural and Intellectual Integrity During Wartime

The novel centers its female protagonists, highlighting the often overlooked role of women in preserving cultural and intellectual integrity during crises. Each of the three women—Viv, Althea, and Hannah—engages in resistance deeply tied to protecting knowledge and safeguarding ideas.

Althea, as a writer, fights against Nazi censorship and the destruction of literature. Hannah, as a librarian, works to protect banned books and raise awareness of Nazi atrocities through her exhibitions.

Viv, in contrast, takes a leadership role in preventing the censorship of ASEs, recognizing the importance of maintaining soldiers’ access to literature. Their efforts serve as a counterpoint to the male-dominated forms of resistance typically portrayed in war literature.

The novel suggests that while men may engage in physical combat, women play a crucial role in ideological and cultural battles. This theme is reinforced by the portrayal of the library as a symbol of resistance, where women like Hannah work to preserve knowledge and counteract censorship.

Memory, Legacy, and the Act of Historical Remembrance

The theme of memory and legacy is central to the novel, particularly in how individuals and societies remember and reckon with past atrocities. Althea, Hannah, and Viv all grapple with the weight of their personal histories and their roles in the broader historical narrative of World War II.

Their journey to Berlin at the novel’s conclusion serves as a symbolic act of remembrance, not just for the destruction of books but for the cultural and intellectual losses inflicted by the war. The memorial they visit is a testament to the importance of acknowledging the past, even its most painful aspects, in order to move forward.

The novel’s structure, spanning multiple timelines and locations, weaves together personal stories with the larger historical context. It suggests that memory is both a personal and collective act, requiring active engagement with the past to preserve its lessons for future generations.

In this way, The Librarian of Burned Books underscores the vital role literature, libraries, and storytelling play in keeping history alive, even in the face of attempts to erase it.