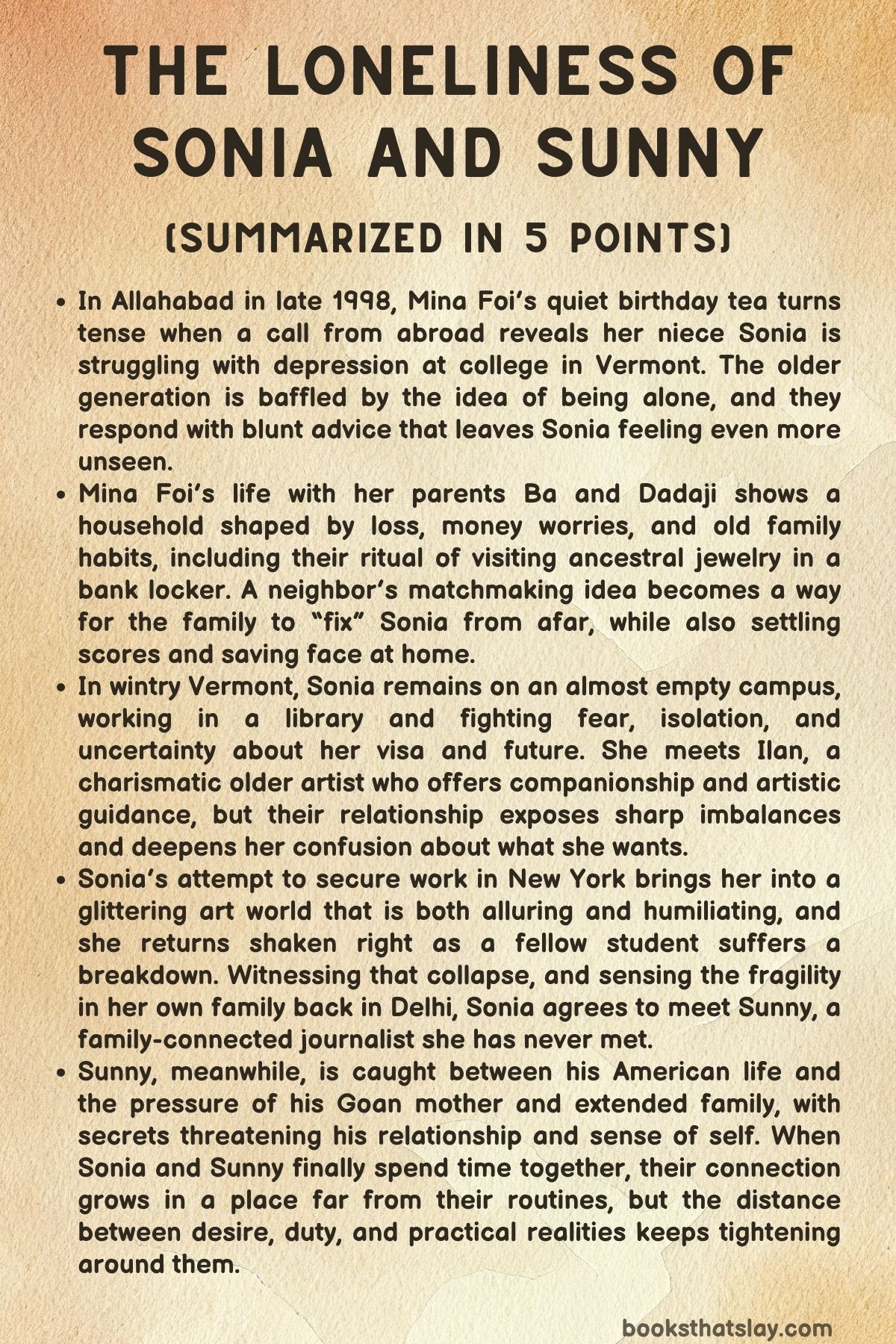

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny Summary, Characters and Themes

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran Desai is a cross-continental novel about family pressure, love, and the strange shapes loneliness can take. It opens in Allahabad with an aging, tradition-bound household that can’t quite grasp what their American-college granddaughter Sonia is suffering through.

From there, the story travels to snowy Vermont, crowded New York, and humid Goa, following Sonia and Sunny as they try to build lives that are theirs, not just extensions of family history. The book balances sharp social observation with intimate emotional detail, showing how migration, class, and desire complicate every choice.

Summary

On December 1, 1998, in Allahabad, Ba, Dadaji, and their divorced daughter Mina Foi sit on a dust-coated veranda, drinking tea and planning Mina Foi’s birthday meal. The family’s routine is steady, bordered by highway noise and guava orchards, yet a long-distance call cracks the calm.

Manav, Mina Foi’s brother living abroad, phones to wish her well and then admits he and his wife Seher are worried about their daughter Sonia, who is studying in Vermont. Sonia has been crying, saying she feels desperately lonely.

Dadaji, used to joint families and constant company, refuses to understand loneliness as a real problem. He decides Mina Foi should speak to Sonia, believing a stern talk might cure her.

When the call finally connects, Sonia describes her American college life in small details—the dorm food, themed dinners, and the strange abundance of pies and sweets. Mina Foi listens with wonder, but Dadaji interrupts with blunt advice: Sonia should stop crying, exercise, toughen up, and remember that studying in America is a privilege won through his efforts.

Sonia tries to say that winter darkness and self-obsessing thoughts are swallowing her, but he repeats that America is friendly and safe, and that loneliness is nonsense. Sonia begins to weep again, the call cuts out, and they let it end there.

The family returns to their day, brushing dust away as if the problem can be swept aside too.

Mina Foi’s birthday continues in the shadow of an old family ritual. Each year she and Ba go to the bank to inspect jewelry stored since their flight from Rangoon decades earlier.

The jewels represent wealth lost and family pride preserved in boxes, and the visit brings up buried grief. Ba recalls a giant Burmese ruby lost during the 1942 escape, a symbol of their decline.

Mina Foi, whose short marriage ended in divorce and whose life has been treated as an unfortunate accident by her parents, feels bitterness rise when Ba casually remarks on her lack of interest in dressing up. A small quarrel leaves them unsettled, then they return home to prepare kebabs for the birthday dinner.

After a formal meal and the sorting of pills, Dadaji announces a plan. The Colonel, a neighbor with whom he plays chess, has an unmarried American-educated grandson.

If Sonia is lonely, Dadaji thinks, a suitable boy from a known family could solve it. Ba agrees quickly.

The proposal also hides a quiet motive: years earlier the Colonel convinced Dadaji to invest in a doomed mill, and Dadaji never forgot the loss. A marriage alliance would feel like repayment without anyone naming it.

The next day they take leftover kebabs to the Colonel’s house and bring up Sonia’s situation. Mina Foi notices a photograph of the grandson—Sunny—and feels a spark of curiosity.

Winter in Vermont presses down on Sonia. Most students leave for internships, but she cannot work off-campus, so she stays in the dorm and works alone in the library.

Days are long, silent, and cold. She catalogues books half-heartedly under a supervisor named Marie, eats cheap ramen, and tries to write stories for her thesis.

Her moods swing from panic to numb calm. She carries a Tibetan amulet called Badal Baba, a small anchor against fear.

One snowy afternoon a tall older man appears at the empty library. He shovels steps, reads art books, and scribbles in a Van Gogh volume.

Sonia protests, and he returns later with owl recordings, odd jokes, and a widening friendliness. He talks about India, mimics monkeys, and is interested in Sonia’s childhood memories in Allahabad.

When he learns she is alone for the winter, he says he is alone too and invites her to dinner. He is Ilan de Toorjen Foss, a painter, theatrical and self-absorbed, yet attentive in a way that feels like rescue.

Sonia is drawn into a relationship with him, part romance and part lifeline, until his demands begin to shape her.

As graduation nears, Sonia argues with Ilan about her future. Her visa is ending; she needs a job sponsor to stay in the U.

S. , and panic about deportation overtakes everything.

Ilan criticizes her “monkey” story, calling it false and too eager to please Western expectations. He urges her to write about real lives such as Mina Foi’s and mocks the idea that arranged marriages are the center of Indian experience.

Wanting to help, he calls his friend Lala Leone Leloup, a New York gallery owner, to arrange work for Sonia. Then Ilan leaves for Mexico, kisses her dramatically, and disappears.

Sonia waits in anxious longing, but he never contacts her again.

She goes to New York to meet Lala and pursue the job. The city greets her harshly: she is tricked at Port Authority by a scammer and scolded by a cabdriver for her naivety.

Lala’s world is glossy and cold. In a luxury apartment filled with famous art, Lala sizes Sonia up, saying a gallery receptionist must be beautiful or shockingly unattractive, and notes Ilan’s taste with a smirk.

Still, she offers Sonia low-paid work, rules for her body and clothes, and a promise to process a temporary visa. Sonia accepts because she has no other way forward.

Back in Vermont, her fragile stability is shaken when a fellow student, Lazlo, has a breakdown. Sonia and her housemate Armando find him rigid on his bed, screaming when touched.

He is taken away and soon flown back to Bulgaria. Armando is shaken by the loss of his only friend.

Sonia, already raw from Ilan’s silence, calls his Mexico number and reaches an angry woman who hangs up. She tries calling home in Delhi, but no one answers.

In Delhi, Sonia’s parents attend a dinner party where men drunkenly rank women by nationality while women try to steer talk toward politics and violence after the Babri mosque destruction. On the drive home, Manav drinks too much and nearly runs his wife down in fury as she opens the gate.

The marriage’s hidden brutality becomes clear. Not long after, Manav phones Sonia privately.

He suggests she meet Sunny, the Colonel’s grandson, who lives in New York. Hurt, lonely, and uncertain about her future, Sonia agrees.

Meanwhile in Allahabad, Ba and Dadaji draft a marriage proposal letter, listing Sonia’s virtues and flaws with comic bluntness. Ba slips in a stolen photo.

The letter reaches Sunny in Brooklyn. He is a shy journalist working nights at the Associated Press, living with his American girlfriend Ulla without telling his family.

Ulla reads the letter and sees Sonia’s photo, and suspicion floods her. She confronts Sunny about secrecy and his divided loyalties.

Their argument exposes a deeper problem: Sunny wants freedom but cannot cut the cord to his mother Babita, whose calls and expectations shadow him. The story pauses on this tension, showing Sunny’s past with Ulla and the cultural friction inside their shared life.

Sonia and Sunny later meet in Goa. Their first encounter is awkward, shaped by family expectation and their own guardedness, but it softens into intimacy as they travel together through old mansions, churches, beaches, and bakeries.

They talk about America’s demands and the exhaustion of being foreign. The relationship becomes real in the small hours and shared swims.

Yet fear stays close: Sunny worries about what they can be, Sonia fears separation, and both sense the weight of families waiting behind them. After leaving Goa they must pretend not to know each other in Delhi.

When Sonia tries for a U. S.

visa to reunite with Sunny, she is refused, labeled too risky to return. She emails Sunny the news, along with word of a neighborhood scandal after they were seen together.

In New York, Sunny reads her message, missing her and feeling the future narrowing.

The final movement shifts to Babita in Goa, alone and frightened by anonymous calls accusing her of missing gold and warning her she will be punished. She also learns her seaside house purchase was illegal and could be taken away.

Sonia, now staying with Babita, talks with her late into the night about loneliness and loss, while her own dreams are haunted by Ilan. When Sunny hears about Sonia’s desperate arrival and Ilan’s looming influence, he travels to Mexico to confront him.

He finds Ilan in a ruined mining hamlet, grandiose and unstable, obsessed with the Badal Baba talisman. After a tense interview, Sunny sneaks into Ilan’s compound, meets a silent young woman terrified of him, and steals the matching amulet from Ilan’s chapel.

He flees through tunnels and deserts, later reading that Ilan has vanished and the talisman is missing. Carrying guilt and responsibility, Sunny returns to Goa.

He arrives at Babita’s house to find light, laughter, and the smell of kebabs. Sonia opens the door, and they reunite—older, thinner, but relieved that the other is real.

Sonia reaches for the battered amulet at his neck. The story closes on their fragile renewal: two people trying to make a life together while the past, family need, and solitary fear still circle near the edges.

Characters

Sonia

Sonia is the emotional center of The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, a young Indian woman whose inner life is dominated by isolation, self-scrutiny, and a fear that loneliness is not a temporary phase but a condition that could swallow her whole. In Vermont she is cut off structurally and culturally—unable to work off-campus, stuck in a near-empty dorm, and facing a winter whose darkness mirrors her mood swings—so her depression is both personal and situational.

She tries to steady herself through routines and talismans like the Badal Baba amulet, but her imagination also turns against her, making her susceptible to romantic projections and dread. Sonia’s relationships reveal a tension between what she wants—connection, safety, a future she can choose—and what she has been trained to accept—family authority, visa realities, and the expectation that a good life should cancel out despair.

She is also a writer in formation, which makes her doubly vulnerable: she searches for a story truer than cliché, yet she is haunted by guilt when she uses Mina Foi’s life as material, suggesting her creativity is entangled with family wounds. Across the novel she moves from passive waiting to active choosing, but that agency is always hard-won, shaped by repeated experiences of abandonment, judgment, and the blunt power of border systems.

Sunny

Sunny is the novel’s quiet counterweight to Sonia, a man who appears gentle and reasonable on the surface yet is deeply conflicted about belonging, duty, and desire. As an Indian journalist living in New York, he has built a life of self-reliance and American intimacy with Ulla, but his family’s pull continues to operate like gravity, especially through Babita’s emotional pressure and the unspoken demand that he represent the family’s honor abroad.

Sunny’s defining struggle is between passivity and action: he often tries to keep everyone calm by smoothing things over, evading hard truths, or saying what a powerful person wants to hear, and then hates himself for it. Yet he is also capable of decisive moral risk, as shown by his journey to Mexico to confront Ilan and recover the amulet.

That trip exposes both his courage and his naivety—he steps into a mythic danger zone not as a hero with certainty but as a frightened man trying to do one clear good thing. Sunny’s love for Sonia grows out of mutual recognition rather than fantasy; with her he feels seen in his fatigue and uncertainty, and his affection is tied to a hope for a simpler, shared future.

Still, even in love he cannot escape the habits of compromise that have kept him afloat, making his arc one of gradual awakening to the costs of neutrality.

Mina Foi

Mina Foi embodies the long, slow ache of a life judged as “unlucky,” and her character gives the book its generational depth. Divorced after a six-month marriage and returned to her parents’ house, she lives in a state of social suspension where her present is defined by what she lost and how the family narrates that loss.

On her birthday ritual at the bank locker, Mina Foi’s resentment flares not just toward her parents’ pity but toward the fact that she was never allowed to develop a self beyond what the family needed her to be. Her dryness on the phone with Manav and her quiet sadness during the kebab dinner reveal a woman who has learned to survive by shrinking her expectations rather than by forgetting them.

Mina Foi’s brief interest in the Colonel’s grandson’s photo and her later fictional resurrection through Sonia’s thesis show that she still carries suppressed desire and unwritten possibilities. She is not simply tragic; she is also perceptive, ironical, and capable of sharp truth, which makes her a silent critic of the household’s moral economy.

Dadaji

Dadaji is a patriarch formed by habit, history, and certainty, and his worldview is built on the idea that family structure is a cure for all existential problems. He cannot comprehend Sonia’s loneliness because he has never had to face a self outside kinship; to him solitude is not a psychological state but a practical impossibility.

His brisk scolding on the phone—exercise, persevere, be grateful—shows an older logic of endurance that treats emotion as indulgence. Yet he is not merely cruel: his generosity is real within his framework, shown by his decision to call Sonia, his pride in her education, and his attempt to “solve” her pain through marriage.

Dadaji’s character also carries the weight of past financial humiliation, especially the failed woolen mill investment, which makes the proposed match with the Colonel’s family feel like quiet revenge disguised as benevolence. He represents the way patriarchal affection can be sincere while still oppressive, because it refuses to recognize the interior lives of younger people as legitimate.

Ba

Ba is the household’s vigilant guardian of order, and her love expresses itself through control, suspicion, and ritual precision. She polices meals, bathing, pill-sorting, and propriety not as empty tradition but as her way of holding chaos at bay—especially the chaos of decline, migration, and broken marriages that haunt the family story.

Her yearly bank visit with Mina Foi shows Ba’s attachment to material memory; jewels become proof of a past dignity that must be counted and re-banded to stay real. Ba’s emotional tightness makes her capable of small cruelties, such as interpreting Mina Foi’s divorce as misfortune she must carry, but her fear is also legible: she worries that loosening her grip will expose how fragile the family’s status truly is.

Even the stolen photograph slipped into the proposal letter shows her ability to cross ethical lines for what she believes is family survival. Ba is a portrait of a woman whose authority is real but secondhand, exercised within the boundaries of her husband’s world.

Manav

Manav, Sonia’s father, is a man split between cosmopolitan success and intimate brutality. In the family phone call he plays the role of concerned modern parent, worried about Sonia’s depression, but in Delhi his dinner-party masculinity is crude and performative, participating in the objectifying talk that reveals how little emotional safety exists behind the polished surface.

His near-murderous act of driving the car at his wife shows the terrifying volatility underneath his charm, suggesting a rage that erupts when his control is challenged. Yet Manav is also pragmatic in his parenting; his proposal that Sonia meet Sunny is presented as protection against loneliness and collapse, a father’s attempt to offer a safer male presence after Ilan.

This mix of care and harm makes him one of the novel’s most unsettling figures: he wants to be loving without relinquishing dominance.

Seher

Seher, Sonia’s mother, lives in the quiet fallout of Manav’s aggression, and her character illustrates what endurance looks like when it is forced rather than chosen. She is present at the dinner party as part of a social unit that keeps women polite and redirecting conversation away from male vulgarity, which shows her practiced skill at managing men’s moods.

The gate incident marks a turning point in her understanding of her marriage; she recognizes not a momentary lapse but genuine intent to harm. That recognition does not instantly free her, but it changes her interior posture, making her more alone inside her own life.

Seher’s emotional reality is mostly offstage, which itself is telling: she embodies the way women’s fear and labor are often rendered background noise in family narratives.

Ilan de Toorjen Foss

Ilan is both magnet and menace, an older painter whose charisma is inseparable from his predatory instability. He enters Sonia’s winter like a mythic rescuer—shoveling snow, offering owl calls, drawing her into conversation—yet his intimacy is built on asymmetry: he becomes her lifeline while keeping his own life opaque.

Ilan’s artistic ego fuels his contempt for Sonia’s writing, accusing her of falseness and cliché while also appropriating her family stories as material he deems “truer,” which is a form of control disguised as mentorship. His theatrical affection and sudden disappearance enact a classic cycle of seduction and abandonment, leaving Sonia trapped in longing and self-blame.

Later, in Mexico, Ilan’s compound and talisman obsession reveal an imagination curdled into paranoia; he treats Badal Baba as both muse and shield, suggesting a man who has turned spirituality into a private fortress. Ilan’s volatility toward Sunny and his eventual disappearance make him a figure of destructive artistry—the kind that consumes others as fuel and then rewrites the damage as destiny.

Lala Leone Leloup

Lala is a sharp-edged embodiment of art-world realism, someone who sees people as surfaces to be curated and sold. Her first interaction with Sonia is transactional and appraising, evaluating her beauty and usefulness with cold honesty that shocks Sonia out of romantic illusions.

Yet Lala is not simply villainous; she offers Sonia a job, clothes, visa processing, and a survival blueprint, indicating a worldview where help is never free but can still be real. She also punctures the myth around Ilan by calling him complicated and refusing to idealize him, acting as a secular corrective to Sonia’s longing.

Lala’s power lies in her clarity, which can feel brutal but also lifesaving in a world that repeatedly exploits Sonia’s innocence.

Babita

Babita is Sunny’s mother and one of the novel’s most complex sources of emotional pressure. Widowed and living alone, she wields guilt, suspicion, and rumor like instruments to keep her son tethered, often reframing Sonia as unstable or opportunistic to protect her own claim on Sunny’s loyalty.

Her manipulation is not abstract cruelty; it springs from fear of abandonment, social precariousness, and the erosion of authority that migration has caused. The threatening phone calls and fraudulent house sale strip her of certainty, revealing a frightened woman whose paranoia is grounded in real vulnerability.

Her late-night conversation with Sonia in Goa shows another side: she can recognize loneliness in others and offer cautionary wisdom, even if she cannot stop weaponizing the same loneliness inside her family. Babita represents how love can become coercive when it is mixed with isolation and unhealed grief.

Ulla (Mary)

Ulla is Sunny’s American girlfriend, and her presence exposes the cultural and emotional asymmetries in Sunny’s life. She is not naïve about compromise—she entered an international student romance knowing there would be frictions—but the proposal letter from Allahabad makes visible how thoroughly Sunny has hidden her from his family, turning her into a private experiment rather than a public commitment.

Her anger is rooted in dignity: she refuses to be an option kept in reserve while Sunny maintains a parallel self for his mother’s approval. Ulla’s voice is a necessary counterpoint to the story’s Indian family logic; she insists on transparency, respect, and adult partnership rather than filial performance.

Even when she argues bitterly, she is asking for a life that does not require erasure.

Satya

Satya is Sunny’s longtime friend and an example of how insecurity can metastasize into betrayal. In Goa he is humiliated by Sunny’s ease—his swimming, his reading, his obvious comfort in the world—and that humiliation becomes jealousy when he senses Pooja’s admiration for Sunny.

Satya’s cruelty is less about Sunny’s real actions than about Satya’s own fear of being ordinary and replaceable. The lies he tells Pooja and Babita reveal a man who chooses temporary control over moral fidelity, and his later guilt shows that he is not monstrous, just weak in the face of envy.

Satya illustrates how male friendship can fracture under the pressure of status anxiety and erotic rivalry.

Pooja

Pooja moves through the Goa section with quiet perceptiveness, caught between loyalty to her husband and a dawning awareness of his pettiness. Her admiration for Sunny’s intelligence is genuine and unguarded, and Satya’s reaction teaches her the cost of speaking honestly in a marriage built on fragile male pride.

She does not openly rebel, but her subtle unease and attempts at kindness show a woman negotiating her safety within a relationship that can punish her curiosity. Pooja’s character suggests how desire often reads first as attention before it becomes confession, and how women in such spaces learn to translate attraction into silence.

Armando

Armando is Sonia’s housemate and a fleeting yet poignant mirror of her loneliness. His panic over Lazlo’s disappearance reveals how precarious friendship becomes in a foreign landscape where one person can be your entire emotional economy.

When Lazlo collapses, Armando’s repeated insistence that Lazlo was his only friend underscores the dorm’s atmosphere of isolation and the thinness of their support systems. He is a reminder to Sonia that her depression is not uniquely hers; it is a shared condition among displaced students.

Lazlo

Lazlo is the novel’s stark warning about what happens when loneliness curdles into breakdown. His rigid, boxed-up room and screaming collapse are almost ritualistic, as if his self has been packed away before his body gives up.

Lazlo’s removal by ambulance and the family’s swift extraction back to Sofia show how mental crises are often handled through disappearance rather than care. For Sonia, Lazlo becomes a possible future she refuses to accept, intensifying her need to find a different path.

Marie

Marie, Sonia’s library supervisor, is a minor character who still matters because she provides a rare form of gentle, non-intrusive kindness. Her gift of the bright yellow coat is practical warmth but also symbolic visibility, a small gesture that acknowledges Sonia as someone worth noticing.

In the cold institutional winter, Marie is one of the few adults who offers comfort without demanding repayment or narrative.

Anand

Anand, the Goan taxi driver, seems comic at first with his habit of stopping to pick up plastic bags, yet he functions as a moral texture in the Goa episodes. His concern for the littered landscape introduces an ethic of care that contrasts with the tourists’ consumption of beauty and history.

The delays he causes force Sonia and Sunny into a slower rhythm, shaping their encounter into something less scripted and more lived-in. Anand represents the grounded local reality that surrounds and quietly resists the visitors’ private dramas.

Clayton

Clayton, the caretaker of the Loutolim mansion, embodies the decayed colonial afterlife of Goa—devout, dutiful, and deeply invested in propriety. His assumption that Sonia and Sunny are married shows how he polices morality through fantasy, arranging their stay into a story that satisfies his values.

His secret voyeurism and masturbation, though they never learn of it, are a dark underside to that propriety: desire repressed into furtive violation. Clayton is a reminder that the house’s beauty and melancholy are not neutral; they are inhabited by living contradictions.

The Colonel

The Colonel functions less as a developed person and more as a node of old power, linking past debts to present marriage schemes. His influence over Dadaji through the failed investment and chess companionship places him inside the family’s private economy of honor and repayment.

Even absent, he represents the social machinery that turns emotional crises into marital transactions.

Ravi and Rana

Ravi and Rana, Sunny’s uncles, provide a blunt alternate reading of Babita’s behavior. Their advice to be ruthless and push her to sell the house is pragmatic, even cold, but it comes from long familiarity with her manipulations and the family’s entanglements.

They are not moral guides so much as survival strategists, showing Sunny a version of adulthood that prioritizes boundaries over harmony.

Betsy and Brett

The American missionaries are background figures who nonetheless sharpen Mina Foi’s sense of abandonment. Their possible absence on her birthday signals how fragile cross-cultural kindness can be, and how quickly small hopes collapse into confirmation that one is forgettable.

In Mina Foi’s world, they become symbols of a foreign promise that never quite returns.

Mrs.

Mrs. Sharma, the neighbor who sees Sonia and Sunny together, is the spark that turns private desire into public scandal.

She represents the surveillance culture of middle-class neighborhoods, where morality is enforced through gossip rather than law. Her role shows how quickly love becomes evidence, and how a single witness can activate an entire social tribunal.

Themes

Loneliness as a lived condition rather than a private flaw

From the first phone call between Allahabad and Vermont, loneliness is treated as a problem that different worlds don’t even agree exists. Sonia’s distress is not presented as a melodramatic phase; it is a full-body experience shaped by time zones, winter dark, institutional rules for foreign students, and the thinness of daily contact.

Her family hears the word “lonely” and translates it into ingratitude or laziness. Dadaji’s bafflement is not simple cruelty; it comes from a worldview where aloneness is structurally prevented by extended family, routine, and constant surveillance.

The novel shows how a person can be surrounded by people and still be emotionally stranded, while another can be physically alone and not recognize the state as abnormal. This mismatch turns Sonia’s depression into something doubly painful: she is suffering, and her suffering has no social language at home.

The American campus, too, fails her. The dorm empties, the visa blocks work, and even her library job becomes a quiet room where her thoughts echo louder.

The “international” food lists and themed dinners underline how institutions offer variety as a substitute for belonging; novelty does not equal care. The loneliness spreads outward, showing itself in Lazlo’s breakdown and Armando’s fear of being left without a friend.

It also appears in Babita’s later paranoia and in Sunny’s own isolation inside his secret life with Ulla. The book keeps returning to the idea that loneliness is not a special event but a climate people live inside, sometimes for decades.

Crucially, relief does not come from a grand cure; it comes from small recognitions—Sonia and Sunny admitting they are tired of self-reliance, Babita and Sonia speaking late into the night, even the awkward early moments in Goa when two strangers begin to risk honesty. The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny suggests that loneliness is not defeated by moral advice or by a forced match but by the slow creation of a space where another person really sees you and stays.

Family obligation, control, and the quiet violence of “care”

The domestic routines in Allahabad look tender on the surface—tea on the veranda, kebabs prepared for a birthday, jewels admired in a bank locker—but the same gestures also operate as systems of control. Ba and Dadaji’s “care” for Mina Foi is inseparable from how they narrate her divorce as her personal failure.

Her misfortune becomes a family story that keeps her in place, grateful and diminished. Even an outing to the bank vault, which could be a moment of shared memory and pride, turns into a reminder that the family’s wealth and lineage are not hers to define.

Ba’s remark that it is “fortunate” Mina Foi never liked dressing up lands like a confiscation of her right to want anything. In this world, love is often administered through supervision: Ba policing the kebabs, Ba ensuring Dadaji gets the last potato, pills sorted and swallowed in a choreographed line.

The book is sharp about how obligation can erase individuality while pretending to preserve it. The marriage proposal for Sonia is framed as rescue from loneliness and also as repayment of an old debt to the Colonel.

The family can call it generosity because the transaction is hidden under affection. Sunny faces a parallel pressure.

His mother Babita’s love is real, but it is also possessive and strategic. Her accusations against Sonia, her guilt tactics, and her ability to pull Sunny into complicity by rewarding him when he criticizes Sonia show how family ties can become emotional blackmail.

Sunny’s secret life with Ulla illustrates another aspect of obligation: the fear of disappointing family is so strong that he chooses deception over open conflict, even at the cost of his relationship. The novel doesn’t reduce family to villains; it shows how people inherit scripts of duty and then reproduce them, often without noticing the harm.

Mina Foi, Sonia, Sunny, and even Babita are all shaped by expectations they didn’t author. What makes the theme painful is its closeness to love—control arrives wrapped in food, advice, matchmaking, and worry.

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny asks whether care that denies choice is still care, and how adults can find a way to belong to family without becoming owned by it.

Migration, cultural in-betweenness, and the cost of reinvention

Life across borders in The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is not presented as a single upward arc or a simplified tragedy. It is a long negotiation with paperwork, accents, money, romance, and the way the past keeps traveling with you.

Sonia’s Vermont winter exposes the physical infrastructure of migration: the student visa that traps her on campus, the empty dorms when Americans disperse, the anxiety that her right to remain depends on pleasing an employer. Her relationship with Ilan begins in a space created by her foreignness—she is alone, he is fascinated, the deserted library is a shelter.

Yet the romance also shows the imbalance that migration can create. Ilan has mobility, confidence, and cultural authority; Sonia has a ticking visa and the feeling that every wrong step could send her back.

When she goes to New York, she encounters a city that profits off her vulnerability, from the Port Authority con to Lala’s evaluation of her body as a workplace asset. Migration is shown as a kind of audition, where the immigrant is constantly assessed.

Sunny’s immigrant life has a different texture. He has built a career and a relationship in Brooklyn, but he lives on two clocks at once.

His nights at the AP, Spanish classes, and American girlfriend mark a present he is inhabiting, while Babita’s letters and proposals drag him into a past that demands loyalty. He cannot fully claim either world.

His secrecy with Ulla is both self-protection and a symptom of cultural split: he fears the judgment of home and fears losing the comfort it still provides. Even in Goa, a place inside India, Sonia and Sunny are migrants in another sense—temporary, on assignment, pretending to be something else for family and society.

Their near-drowning on the red-flag beach echoes the theme’s risk: to cross into a new life is to enter waters that can save or swallow you. The book keeps underlining that reinvention is expensive.

It can bring freedom, love, and perspective, but it can also make you unrecognizable to those who raised you and to yourself. The emotional toll is not only homesickness; it is the endless effort of translation—of feelings, behavior, ambition, even the meaning of being alone.

Migration here is a condition of permanent adjustment, where belonging is always provisional.

Power, gender, and the ways people become usable to others

Across generations and locations, the novel tracks how power operates through gendered expectation and economic dependence. Mina Foi’s divorce is treated as damage to her worth, and the family’s response is to store her in the home, not because they hate her but because the social order leaves little room for a divorced woman to live freely without shame.

Her life becomes a quiet demonstration of how patriarchy can be enforced by women as well as men—Ba’s vigilance, her moral policing of food and propriety, sustains a hierarchy that keeps Mina Foi small. Sonia’s experiences in America might look like escape from that structure, yet she finds new versions of it.

Ilan’s charm masks a patronizing authority over her art and identity; when he criticizes her story as false and “self-orientalizing,” he is also claiming the right to define what her truth should be. Lala’s job interview turns Sonia into an object evaluated for saleability; beauty becomes a job requirement and language becomes another gate.

The message is blunt: even in cosmopolitan spaces, women’s bodies and stories are treated as resources for others’ projects. Sexual vulnerability enters again in Goa through Clayton’s spying and masturbation outside Sonia and Sunny’s room, a reminder that privacy and safety are never guaranteed to women, even in moments of happiness.

Babita embodies another facet of gendered power. As a widowed mother, her social capital is fragile, and she responds by tightening her grip on Sunny.

Her manipulation is not excused, but it is contextualized as a survival method learned in a world where women without husbands are easy targets for rumor, fraud, and threat. The anonymous calls about missing gold and the illegal house sale show how quickly a woman’s property and security can be challenged.

Meanwhile, Sonia’s parents’ dinner party in Delhi reveals male entitlement in its most casual form—women rated like menu items, violence normalized to the point that Manav’s near-murder of his wife grows from a drunken quarrel into a moment of terrifying clarity. The novel’s power dynamics are not only male-over-female; they also include cultural power, class power, and artistic celebrity power.

Ilan’s fame allows him to disappear people emotionally and perhaps physically. Sonia and Sunny must continually measure themselves against forces that treat them as usable—family debts, visa systems, lovers’ egos, employers’ tastes.

What emerges is a map of how power is exercised in ordinary scenes, not only in dramatic confrontations. The theme argues that love and safety require resisting these uses, creating relationships where neither person is a solution, a debt payment, or a prop for someone else’s story.