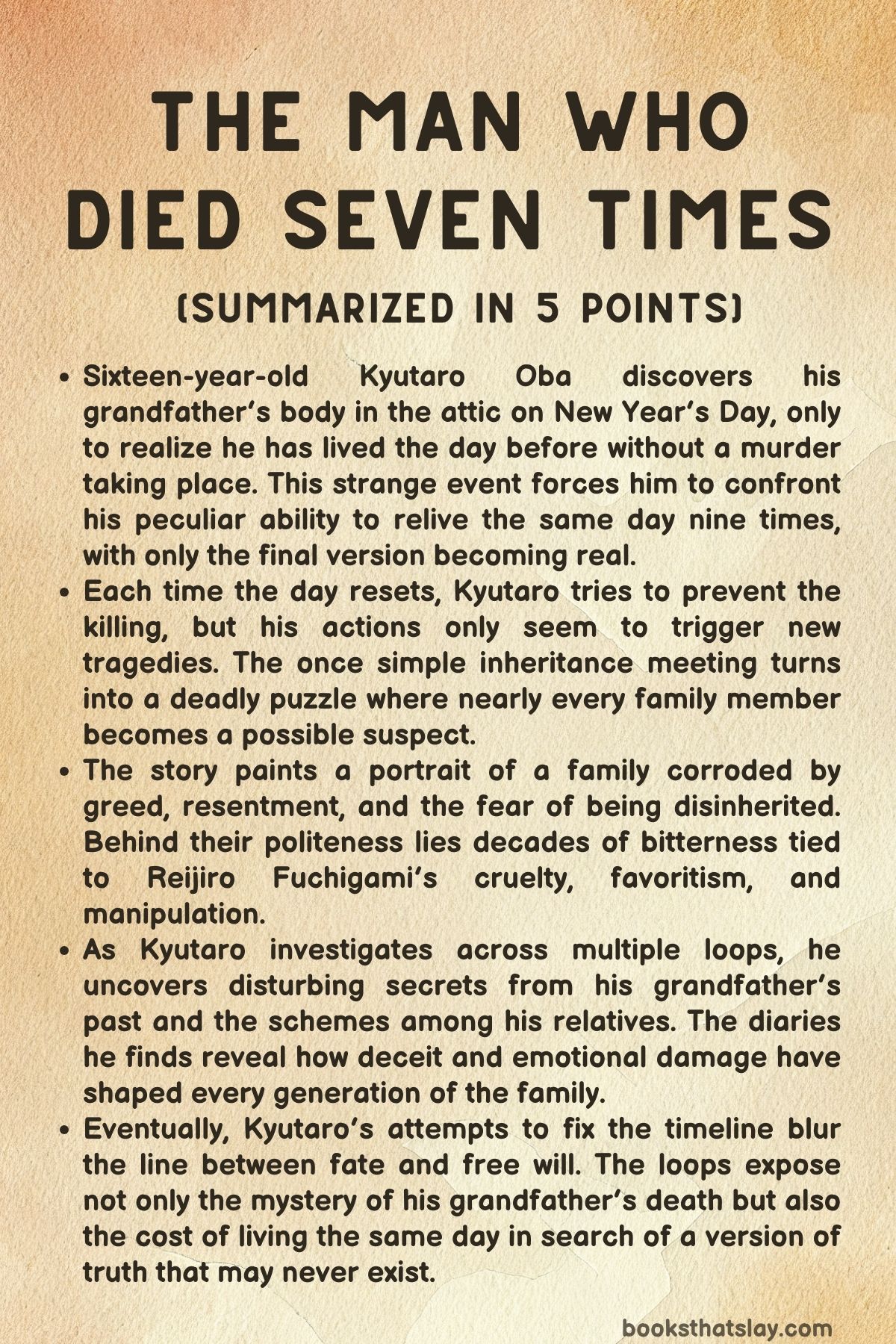

The Man Who Died Seven Times Summary, Characters and Themes

The Man Who Died Seven Times by Yasuhiko Nishizawa is a psychological mystery that blends family drama with speculative elements of time repetition. The story follows sixteen-year-old Hisataro “Kyutaro” Oba, a boy cursed with reliving the same day multiple times—a condition he calls “the Trap.”

When his wealthy grandfather, Reijiro Fuchigami, is murdered during a tense New Year family gathering, Kyutaro must use his ability to uncover the truth. Each repetition reveals new secrets and rivalries within the Fuchigami family, as Kyutaro struggles to prevent the murder and confronts the darker side of human ambition and fate.

Summary

Kyutaro Oba, a teenager burdened with a strange curse that forces him to relive the same day nine times, visits his grandfather Reijiro Fuchigami’s mansion for the New Year. The family reunion is an uneasy one, filled with long-standing resentment and competition over inheritance.

Reijiro, founder of a successful restaurant empire, has made and revoked several wills over the years, leaving his daughters Kamiji, Kotono, and Haruna, and their children desperate for favor. During the gathering, Reijiro announces he will finalize his will that very night.

Each relative reacts with anxiety or ambition, while Kyutaro, cynical from his repeated experiences with time loops, simply observes—until he finds his grandfather dead in the attic the next morning.

Kyutaro soon realizes that time has reset. The day begins again exactly as before, and his grandfather is alive.

He understands that “the Trap” has ensnared him once more. The curse allows him to alter small events, though he alone remembers what happens in each iteration.

This time, however, the stakes are higher: Reijiro’s death recurs despite Kyutaro’s interventions, each loop leading to a new version of the same tragedy. In the first repetition, he sees his cousins Runa and Fujitaka secretly meeting and scheming to influence the will by proposing marriage to strengthen their claim.

When Reijiro ends up dead again, Kyutaro suspects their involvement.

In subsequent loops, Kyutaro tries to change small details—avoiding the attic, warning his cousins, and confronting them—but the outcome remains the same. Each day reveals new truths.

Runa’s sister Mai harbors feelings for Fujitaka, and her jealousy drives her into fits of rage. When Kyutaro exposes the affair, Mai attacks her sister, deepening the family rift.

Despite his efforts to divert them, Reijiro dies again, the weapon changing from a vase to a sake bottle. Kyutaro begins to realize that every adjustment he makes only causes another person to commit the murder instead.

The same death keeps repeating under different circumstances, and he starts to question whether he can ever change fate.

As the loops continue, Kyutaro learns more about his family’s corruption. Searching his grandfather’s study, he discovers old diaries filled with notes about business deals, manipulations, and personal betrayals.

Reijiro had orchestrated the downfall of his own sons-in-law, paying people to ruin their reputations for his amusement. He pitted his children against each other, delighting in their desperation for his approval.

These revelations crush Kyutaro’s remaining faith in his family and confirm that greed and resentment are at the heart of every tragedy that unfolds.

In later loops, Kyutaro attempts to keep everyone in one place to prevent any opportunity for murder. He hides the suspected weapon, the vase of orchids, and convinces Aunt Kotono to organize a group meeting.

Despite his best planning, Reijiro still dies—this time from an apparent accident, slipping on Runa’s dropped earring. Furious and helpless, Kyutaro understands that the event itself has become inevitable, the specific cause changing each time but always leading to the same outcome.

The loops seem to enforce some kind of cruel destiny, mocking his attempts to outwit it.

On his eighth loop, Kyutaro tries to restore the original sequence of events exactly as they first happened, believing deviation causes the death. He joins his grandfather for drinks, listens to his rambling conversation, and avoids interference from others.

But Reijiro collapses mid-conversation from a heart attack. His relatives, realizing his death, conspire to disguise it as murder so they can manipulate the inheritance in their favor.

Runa and Fujitaka attempt to frame Emi, the family’s assistant and Kyutaro’s quiet love interest, by planting her fingerprints on the vase. This discovery leads Kyutaro to the truth: there was never a true murder to prevent.

Reijiro’s death was natural each time; the supposed “murders” were all schemes invented by his greedy family members after the fact.

In the final loop, Kyutaro confronts his grandfather directly and forbids him to drink, revealing the manipulation and decay within the family. Startled by his grandson’s conviction, Reijiro promises to change.

Sober for once, he completes his will peacefully, naming Fujitaka and Runa as heirs to his business and sharing the estate equally among everyone else. For the first time, the day ends without bloodshed.

Kyutaro feels the cycle has finally been broken.

When he wakes the next morning, January 3rd, everything seems normal. His grandfather is alive, the family reconciled, and the business stable.

Yet Kyutaro senses something is still off. Emi, meeting him later, accidentally calls him by a name from an earlier loop, proving she remembers events that should have been erased.

She explains that he had misunderstood the loop’s timing—it was actually January 3rd repeating, not January 2nd. He had once died during one of the cycles, slipping on an earring, and that death caused him to lose an entire loop’s memory.

The realization unsettles him: he may never know how many versions of the same day he truly lived through.

Months later, life appears calm again. The succession ceremony confirms Fujitaka as the new head of the Fuchigami family.

Yet old rivalries soon resurface. Runa and Fujitaka’s relationship disintegrates, leading to renewed bitterness among the relatives.

Kyutaro, now older in spirit than his years, wonders whether the Trap will someday return—forcing him again to relive not only time but the endless cycle of human greed and moral decay.

In The Man Who Died Seven Times, Yasuhiko Nishizawa explores the limits of control, the repetition of fate, and the moral cost of knowledge. Kyutaro’s time loops mirror the patterns of obsession, ambition, and resentment within his family, suggesting that some events repeat not because of time itself, but because people never truly change.

Characters

Hisataro “Kyutaro” Oba

Kyutaro, the teenage protagonist of The Man Who Died Seven Times, is shaped by the Trap, a nine-iteration time loop that leaves him prematurely jaded and hyper-analytical. The loops give him tactical power but also moral fatigue: he learns that saving everyone is impossible, so his instincts drift toward self-preservation even as his conscience keeps dragging him back into the fray.

His love for Emi exposes a softer core beneath the cynicism, and his repeated attempts to prevent his grandfather’s death trace a coming-of-age arc from manipulator to responsible actor. By the end, he recognizes that the true challenge is not solving a puzzle but resisting the family’s corrosive schemes and forcing difficult, sober changes—literally demanding sobriety from his grandfather and accepting exclusion from the inheritance to protect others.

Reijiro Fuchigami

Reijiro is the volatile patriarch whose whims and cruelties seed the very chaos that later seems like fate. Once a destructive gambler and drinker, he rebuilds an empire yet never stops treating his family as pieces in a private game, rewriting wills on a whim and even engineering scandals to heighten the drama around succession.

Senility blurs his judgment, but the lasting harm comes from his deliberate manipulations: the origami-crane “method,” the rotating heirs, and the sustained emotional blackmail that pits daughters and grandchildren against one another. His repeated “murder” is revealed as death by overdrinking or natural causes followed by opportunistic staging, making him both victim and author of the family’s moral collapse.

Emi

Emi begins as a seemingly peripheral attendant but gradually becomes the moral and intellectual counterpoint to Kyutaro. Her calm defiance—accepting or declining heirship on her own terms, rejecting Ryuichi’s transactional proposal, and confronting class contempt—marks her independence in a house obsessed with status.

She sees through the family theater and ultimately sees through time itself, deducing the missing loop and forcing Kyutaro to reexamine his assumptions. By choosing love and clarity over power, she models the agency and honesty that the Fuchigamis lack, and her memory of events anchors the story’s final realignment.

Yoshio

Yoshio, Kyutaro’s brother, plays the brash opportunist whose bravado masks insecurity within the inheritance scrum. His willingness to drink with Reijiro and his furtive movements with the orchid vase show how easily he can slide from joker to dangerous participant when power beckons.

He mirrors the family’s reflexive appetite for advantage—quick to posture, quicker to improvise—and becomes one of several “substitute” killers produced by a toxic environment rather than singular malice. In Kyutaro’s evolving moral lens, Yoshio is less a mastermind than a weather vane for the household’s shifting currents of greed.

Fujitaka

Fujitaka’s arc entwines ambition with pliability: he is bold enough to court inheritance through a taboo romance with Runa, yet malleable enough to be steered by her strategic mind. His complicity in staging a murder after a natural death reveals a capacity to rationalize wrongdoing when the prize seems near.

Even his later elevation as successor cannot stabilize him, as the breakup with Runa exposes how little substance underlies their alliance once the performance of unity no longer serves them. He represents the heir manufactured by pressure rather than merit, a successor whose crown sits uneasily because it was chased through shortcuts.

Runa

Runa is the family’s most agile schemer, combining charm, audacity, and a keen sense for leverage. Her secret affair with Fujitaka is less romance than tactic, a move to consolidate name and fortune by bending tradition to her will.

She weaponizes symbols—the ochre earring, the orchid vase, fingerprints—to script narratives that keep her options open, even proposing to frame Emi when fate hands her a natural death to exploit. Yet Runa’s brilliance is also her prison: the same calculating instinct that helps her win rounds ensures lasting intimacy slips away, and when the engagement collapses, it reveals the emptiness of victories won by manipulation.

Mai

Mai’s jealousy toward Runa turns her into an accidental antagonist, a reminder that in a house of constant comparison even love becomes a contest. Humiliation sharpens her into a ruthless truth-teller who exposes her sister’s secrets with surgical calm, and in some loops she becomes another potential “substitute” killer shaped by wounded pride.

Unlike Runa, Mai does not plot long games; her actions surge from emotion, which makes her both more human and more dangerous in volatile moments. She embodies the collateral damage of Reijiro’s dynastic theater—someone who might have been kind if she weren’t forced to compete for visibility.

Kamiji

Kamiji, Kyutaro’s status-fixated mother, illustrates how parental fear mutates into ambition. Once harmed by Reijiro’s vices, she now pursues his favor with the fervor of a convert, pressing her children into the inheritance race and lashing out at perceived social inferiors like Emi.

Her eventual role in one loop’s fatal escalation underscores how desperation erodes judgment; righteousness yields to rage when opportunity or insult presents itself. Kamiji is tragedy by assimilation: in trying to escape the patriarch’s power, she becomes fluent in it.

Kotono

Kotono is the dutiful daughter who stayed, rebuilt, and runs the Edge Group, yet her strength is braided with compromise. She protects the patriarch’s image, manages his senility with the origami-crane charade, and balances the company’s needs against a family addicted to favoritism.

Her willingness to orchestrate gatherings at Kyutaro’s urging shows practicality and a desire for order, but her silence about Reijiro’s decline helps sustain the theater that keeps everyone at risk. She stands as the story’s institutional conscience—capable, burdened, and not quite brave enough to end the pageant she maintains.

Haruna

Haruna operates as both rival and chorus, a sister who fled Reijiro’s earlier cruelty yet remains tethered by the promise of restitution through inheritance. Her reactions—screams that discover bodies, scolding that inflames quarrels—keep the household’s dramas visible and loud.

She is less strategist than amplifier, but in a family where perception is currency, amplification has weight. Haruna’s presence shows how long harm echoes: even those who left return to the same stage when the will is rumored to change.

Ryuichi

Ryuichi, the young assistant, is ambition without pedigree, eager to convert proximity into power. His flirtation with Emi, swiftly curdling into threats when rejected, reveals entitlement learned from watching the Fuchigamis play.

In several loops he becomes a plausible killer simply by being near the machinery of succession and by chasing recognition in a system that rewards audacity over ethics. Ryuichi is the ecosystem’s natural byproduct: an outsider remade in the family’s image, aspiring to win by the same cruel rules.

Kiyoko

Kiyoko, the maid and quiet witness, anchors the narrative with small truths—the missing red origami paper, the sighting of Ryuichi with the vase—that puncture the family’s self-serving stories. Her observations expose how the household runs on fragile props and routines, and how easily those props can be rearranged into evidence of guilt.

She holds no overt power, yet information makes her the most subversive figure in a house addicted to secrecy. In a story about performative inheritance, Kiyoko’s plain facts are the rare acts that are not performance.

Mr. Munakata

Mr. Munakata, the absent-present lawyer, is the story’s legal metronome whose missed entrance on the supposed final day becomes the clue that time itself is off-beat.

His routine visits legitimize Reijiro’s annual whims, turning caprice into paperwork and thereby laundering family politics into formal order. When he fails to appear, the rhythm breaks, prompting Emi’s deduction that exposes the lost loop and forces a re-reading of events.

He personifies how institutions can stabilize dysfunction—and how their small disruptions can reveal truths no one intended to see.

Hitoshi Kanagae

Hitoshi, Runa’s disgraced father, lurks at the edge of the action as a casualty of Reijiro’s engineered scandals. His fall illustrates the patriarch’s reach and the way private ruin is deployed as public lesson to keep the clan obedient.

Even offstage, Hitoshi’s humiliation fuels Runa’s urgency and the cousins’ bitterness, proving that exile and silence still shape the battlefield. He is the cost ledger of the family game, a reminder that every spectacle demanded a sacrifice.

Mayu Tsurui

Mayu is the hired seductress whose role in framing a relative turns scandal into strategy. She demonstrates how the family’s moral contagion spreads outward, recruiting strangers into its scripts and reducing human intimacy to a tool.

Her presence in the diaries converts suspicion into evidence of Reijiro’s deliberate cruelty, hardening the cousins’ resolve against him. Mayu’s brief, instrumental appearance shows that in this world even outsiders are drafted into the choreography of power.

Themes

Time, Agency, and the Trap of Repetition

Kyutaro’s “Trap” imposes a strict architecture on time that tempts him with godlike control while steadily shrinking his freedom. The loops promise mastery—test answers memorized, outcomes optimized—but the price is psychic erosion.

Each reset teaches him how to steer small events, yet the larger arc proves stubborn: Reijiro keeps ending up dead, whether by blunt force, accident, or natural failure. The pattern exposes a paradox: the more Kyutaro interferes, the more contingent variables multiply, producing new culprits, fresh motives, and alternative paths to the same endpoint.

What looks like determinism from a distance is, up close, a tightening net of unintended consequences. The ninth-day “definitive version” tempts him to game reality, but his victories feel hollow because they are purchased by eight days of solitary memory, a private history nobody shares.

When the narrative finally reveals that the apparent calendar itself is misread—and that Kyutaro even died in one iteration he cannot recall—the theme widens from a puzzle-box conceit to a claim about human perception: our grasp of cause and effect is fragile, and certainty can be a mirage constructed from fatigue, grief, and selective memory. Agency survives here not as omnipotence but as responsibility for limited, humane choices—keeping the vase out of circulation, confronting lies, insisting that Reijiro stop drinking.

Time does not bend into a perfect line under Kyutaro’s will; it yields only when he abandons the fantasy of total control and accepts that care, rather than cleverness, is the only reliable intervention. The Trap thus becomes less a superpower than a moral laboratory, revealing how obsession with control can prolong calamity, while precise, modest acts—telling the truth, protecting one person from harm—are the only forms of freedom that endure when clocks refuse to stay put.

Family Legacy and the Economics of Affection

Inheritance in The Man Who Died Seven Times is never simply a transfer of assets; it is a currency that buys performances of love. Reijiro’s annual reshuffling of wills converts intimacy into a competitive market, pricing each relative’s loyalty according to fleeting caprice.

Bright tracksuits and chanchanko vests turn the gathering into a pageant in which children and siblings posture for a patriarch who has monetized attention. The Edge Group’s success sustains the household materially, but the emotional cost is steep: daughters who once fled his cruelty now supplicate, cousins rehearse alliances disguised as romance, and even incorruptible kindness becomes suspect because favors and titles sit in the background of every conversation.

The diaries expose the rot beneath this economy: a patriarch who choreographs demotions, pays for entrapment schemes, and treats his family’s reputations as chips at a table. The effect on the next generation is corrosive.

Runa and Fujitaka mistake proximity to power for destiny; Mai’s jealous eruption shows how scarcity of recognition pushes siblings into rival camps; Kyutaro himself, exhausted by repetition, initially construes his condition as a resource to be hoarded for survival. The legacy at stake is not just a business but a moral climate in which people learn that love must be leveraged to secure position.

The eventual redistribution—naming successors while sharing the estate—offers only partial repair, because the habits formed under scarcity do not vanish overnight. Even after the apparent settlement, the engagement collapses and rivalries reignite, proving that money can endow a dynasty but cannot guarantee inheritance of trust.

The book’s harsh insight is that families built around a fortune risk adopting its logic: dividends are counted, debts remembered, and every gesture audited for advantage until affection itself feels like a transaction ledger.

Performance, Staged Crime, and the Theater of Reality

Again and again the story shows people staging scenes to win advantages: orchestrated confrontations, planted earrings, and even counterfeit murders. What begins as a whodunit becomes a study of why all these people keep acting as if they are on a set.

Reijiro leads by example, treating succession as spectacle. His diaries reveal a director’s mindset: hire this person, nudge that scandal, set up a reveal, and stand back as chaos delivers entertainment and leverage.

The household learns the lesson too well. After Reijiro dies of drink or strain, others rush to retrofit the corpse to a narrative that profits their faction.

A vase with the right fingerprints can transform happenstance into weaponized story; an earring dropped at the correct stair turns misstep into indictment; a rumor placed in the right ear transmutes spite into policy. Kyutaro’s loops amplify the theatrical vibe because he is the lone audience member who remembers every rehearsal.

He experiments with blocking and timing—keep these cousins here, send that aunt there—only to discover that a different understudy is ready to step into the role of killer. The point is not that truth is unknowable but that truth in this family is constantly outbid by a better script.

Even the eventual clarification—that Reijiro’s deaths are not murders—does not dismantle the stage; it only reveals that the most persuasive fictions have been layered over accidents and frailties. The antidote arrives when Kyutaro stops producing scenes and starts dismantling props: hide the vase, refuse to frame Emi, insist on sobriety.

By rejecting dramaturgy, he allows reality to be ordinary again, even if ordinary means anticlimax, disappointment, and the stubborn fact that people still quarrel once the curtain drops.

Moral Ambiguity, Complicity, and the Cost of Survival

Few characters fit cleanly into categories of villain or victim. The patriarch is both a self-made founder and a manipulator who engineers suffering.

Runa is tender with her sister one moment and ruthless the next. Kyutaro saves lives in some loops and endangers them in others, sometimes by doing exactly what looks prudent.

The loops force him into a triage ethic: if he cannot save everyone, he tells himself, he must at least protect himself or the person he loves most. That rationale hardens into a worldview where motives are constantly traded off against outcomes, and guilt becomes a tax paid by whoever was closest to the last bad choice.

Complicity spreads through the household not just through malice but through exhaustion and rationalization. The fight in the banquet hall escalates because years of small surrenders—silences kept for the sake of peace, favors accepted against better judgment—have built pressure no one is willing to acknowledge until crockery flies.

The theme’s sharpest edge appears when the family uses death as an instrument. Reframing a heart attack as murder is not only a legal risk; it is a moral convenience that converts grief into a tactic.

Kyutaro’s turning point arrives when he resists the easy route of a tidy narrative and accepts a messier, accountable one: there is no killer to unmask, only a pattern of choices to interrupt. The book argues that survival without reflection drifts into complicity, while survival with responsibility requires naming harm, even when it comes from those who fed you, taught you, or promised you a future.

In the end, the family remains flawed, but the possibility of a less compromised life begins the moment someone in the room refuses to benefit from a lie.

Addiction, Decline, and the Fragile Body

Reijiro’s drinking is not atmospheric detail; it is the mechanical heart of the plot. Alcohol turns from social lubricant to lethal variable, governing whether the day ends in sleep or collapse, reconciliation or staged crime.

The patriarch’s body becomes a site where decades of exertion, guilt, and indulgence appear as arrhythmia, falls, and vulnerability to suggestion. His career resurrection—gambling wins, stock market coups, restaurant expansion—promised that willpower could rewrite destiny, but the body keeps a second ledger that cannot be falsified.

Each loop exposes how casually the family treats that ledger. Relatives focus on signatures, cranes, and colors, while the most urgent intervention would be water, rest, and distance from the sake bottle.

The cruel irony is that the household, trained by Reijiro’s past despotic whims, hesitates to police him now that his whims are self-destructive. Addiction, here, is also institutional: the family is hooked on the adrenaline of crisis.

Announcements about heirs give everyone a reason to postpone compassion; the next reveal is always minutes away. Kyutaro’s late decision to force a public promise of sobriety is therefore both medical and symbolic.

It places the patriarch’s body ahead of the company’s paperwork and rejects the myth that a sovereign man answers to no one. The aftermath shows how fragile victory is: even with drinking halted for a time, relationships remain volatile, and no single pledge repairs years of damage.

Yet the insistence on health reframes what counts as success. Living grandfather, messy estate, awkward dinners—this, the book suggests, is a better outcome than a perfect will drafted over an avoidable death, because it respects the truth that futures are built on bodies, and bodies must be protected before legacies can be.

Perception, Memory, and the Unreliable Map of Reality

The final reveal—that Kyutaro misread the calendar and even lost an iteration to his own death—recasts the entire case from a puzzle solved to a perception corrected. Throughout the loops he treats recall as absolute, scrupulously reproducing schedules and conversations, but the story asks a harder question: what if the historian is part of the error term?

Repeated scenes and identical outfits make distinct days look like clones; senility makes new statements sound like echoes; sleep deprivation and alcohol skew timestamps; grief tunnels attention toward clues that fit a preferred theory. The Trap therefore functions as a critique of certainty.

To know a day perfectly, one would need not just memory but corroboration from minds untouched by fear and desire—an impossibility inside this family. Emi’s slip at dinner, calling Kyutaro by a name tied to an earlier loop, cracks the frame.

Her observation exposes gaps in his narrative and shows that memory is collective before it is personal; reality stabilizes only when someone else can confirm where the seams are. This theme also interrogates genre expectations.

In a classic closed-circle mystery, evidence accumulates toward a reveal with a satisfying snap. Here, evidence sometimes accumulates toward a gentle correction: the map was flawed, the compass sticky, the traveler overtired.

The effect is humbling rather than deflating. It invites a form of maturity in which one’s own cognition is an object of suspicion, and therefore kindness becomes a practical epistemology.

If those around you might be misremembering—and you might be too—then patience, disclosure, and verification are not soft virtues; they are the only tools that keep shared reality from slipping through the floorboards.

Desire, Jealousy, and the Politics of Intimacy

Romantic energy in the mansion is never private; it is collateral in the succession struggle. Runa and Fujitaka’s secret affair mixes genuine attraction with ambition, each feeding the other until boundaries blur.

Mai’s jealousy is authentic pain, yet it is also sharpened by the knowledge that affection might decide who ascends. Ryuichi’s proposal to Emi reads less like a promise than a corporate merger, and his wounded pride at her refusal exposes a worldview where love is a lever for promotion.

Kyutaro’s affection for Emi, in contrast, registers as the book’s ethical counterpoint. He botches confessions, misreads signals, and stumbles through awkwardness, but he refuses to weaponize her position or fingerprints when pressured.

Intimacy, then, becomes a diagnostic: if you claim to love someone, do you grant them freedom or fold them into a plot? The affairs around the attic repeatedly flip from tenderness to strategy the moment inheritance is mentioned, revealing how scarcity poisons even the most private attachments.

The aftermath confirms that relationships formed under the shadow of advantage do not hold. Runa and Fujitaka’s engagement disintegrates once the pageantry ends, suggesting that passion yoked to politics cannot sustain itself in ordinary daylight.

Kyutaro and Emi’s closing exchange, by contrast, is grounded in recognition and honest talk about the nature of the loops. The book refuses tidy romantic closure, yet it does articulate a standard: love that survives beyond a crisis is the kind that can speak plain truth even when that truth threatens one’s standing.

In a house where desire is constantly audited for strategic value, that plainness feels radical, and it becomes the seed of a healthier future, however unstable the family remains.