The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey Summary, Characters and Themes

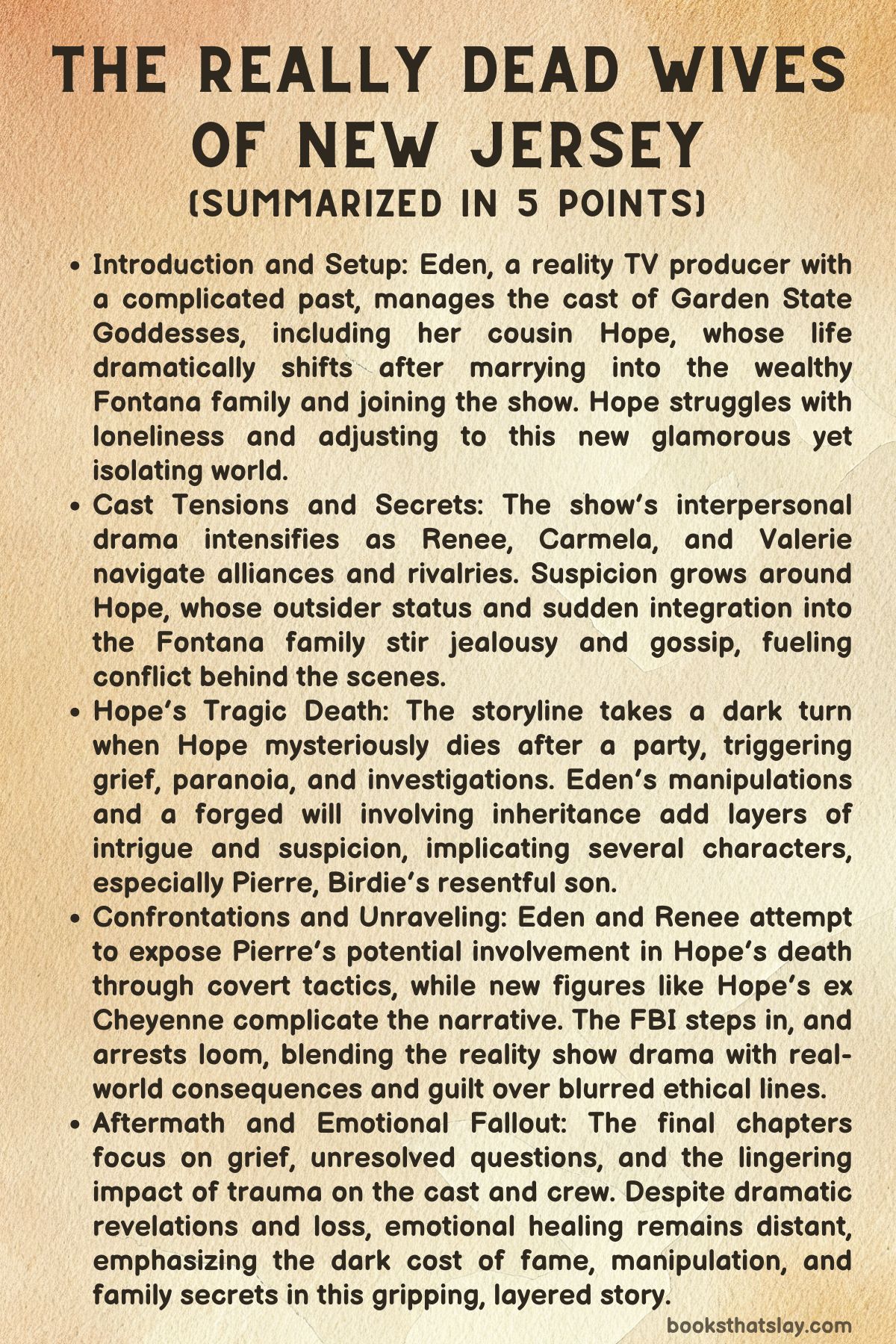

The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey by Astrid Dahl is a sharply written, darkly satirical novel that skewers the artifice of reality television, the dangers of secrets, and the often predatory nature of fame. Set in the glamorous yet treacherous world of Garden State Goddesses, a top-tier reality show, the story follows Eden Bennett, a shrewd showrunner, and her estranged cousin Hope, a former cult member thrust into the spotlight.

Dahl crafts a tense and emotionally charged narrative full of betrayals, manipulations, and twisted relationships. With its biting humor and high-stakes drama, the book offers a layered exploration of identity, trauma, and ambition.

Summary

The story begins with Eden Bennett, a thirty-seven-year-old producer at the height of her career, newly minted as the showrunner of Garden State Goddesses, a wildly popular reality television show. Eden has long abandoned her initial idealism as a documentary filmmaker and now thrives in a world that rewards manipulation, spectacle, and emotional exploitation.

Her latest bold move involves casting her estranged cousin, Hope Fontana—formerly Hope Bennett—as a fresh face on the show. Hope has recently escaped a repressive, cult-like religious sect known as Brother God and is now married into the powerful Fontana family through Leo, Eden’s ex.

Eden’s decision to bring Hope into the show is calculated: it promises compelling TV, solidifies family alliances, and injects mystery into the narrative.

Hope, sheltered and emotionally delicate, is overwhelmed by her new environment. Her wedding to Leo is a lavish spectacle, and her new home in Shady Pond is a world away from her modest past in Weed, California.

Her talents as a singer and songwriter, as well as her gentle presence, contrast sharply with the hardened personas of the other cast members. Despite Eden’s cold, utilitarian view of Hope, the newcomer possesses an intangible magnetism.

Eden quickly recognizes that Hope could be a powerful narrative driver—but also a potential threat.

As Hope acclimates to the cast—which includes fierce personalities like Carmela, Valerie, Birdie, and Renee—she struggles with alienation, suspicion, and an increasing sense of disorientation. Carmela immediately views Hope as an interloper, while others like Renee become cautious allies.

Hope attempts to remain grounded through small acts of resistance—choosing simple meals over extravagant ones, resisting Eden’s branding of her—but the forces around her are relentless. An Instagram post Eden orchestrates ends up exposing Hope to her dangerous ex, Cheyenne, who sends a haunting photo of her father’s scorched Bible.

The sense of surveillance and vulnerability intensifies.

The group trip to Birdie’s opulent estate, Château Blanche, and later to Rhode Island, becomes a crucible. Hope is mocked, humiliated, and questioned aggressively about her past.

Carmela, increasingly hostile, accuses her of hiding something and brands her a “shady freak. ” Hope, however, remains mostly calm through the onslaught.

The fractures between performance and truth widen as Birdie’s erratic behavior and alcoholism become more evident. Hope’s place in the group becomes increasingly precarious as both her past and her secrets threaten to surface.

Tensions come to a head at a televised charity gala where Ruby, Renee’s daughter, performs a song that subtly indicts Renee’s emotional neglect—an indirect consequence of her affair with Hope. Renee and Hope’s relationship, previously hidden from public view, is now marred by guilt and instability.

Hope’s emotional withdrawal and Renee’s maternal guilt clash violently. Hope reveals shocking truths: Leo condoned their affair because he had his own long-standing affair with Carmela.

Hope, buoyed by this grotesque symmetry, envisions a strange double life. But Renee is shaken and pulls away.

Soon after, Hope collapses in front of the cast, muttering fragmented phrases and invoking the biblical figure Delilah. She dies on the spot.

The atmosphere descends into chaos, and just as emergency responders arrive, the FBI bursts in to arrest her—for the arson and murder of her parents, tipped off by Cheyenne. Eden is stunned into collapse.

The aftermath is swift and brutal. Renee sends Ruby to live with her father.

Leo, drunk at Carmela’s nail salon anniversary event, accuses her of poisoning Hope and stabs her with a nail file. Dino, Leo’s brother, kills Leo in front of cameras.

With Hope dead, Eden and Renee attempt to uncover the truth behind her final days. Eden becomes obsessed with the footage, trying to pinpoint who was responsible.

Her suspicions turn to Cheyenne, who had knowledge of Hope’s dark past and may have manipulated others. When Renee visits Eden in a drugged haze and reveals Birdie had added Hope to her will, a new suspect emerges—Pierre, Birdie’s son.

Pierre had always been hostile to Hope and now appears to have both motive and means.

Eden, Renee, and Valerie hatch a plan to search Pierre’s home. Under the guise of emotional healing, they gain entry and drink his drugged smoothies while investigating.

Luz, the housekeeper, confesses that she was asked by Pierre to give Hope a martini the night she died. Pierre’s erratic behavior and desperation mount.

As Eden and Renee fake being more intoxicated than they are, they record Pierre’s reactions during a confrontation. The situation spirals when Pierre’s supplier enters the house in front of the police, sealing Pierre’s fate.

Pierre tries to flee but is arrested. Flashbacks reveal he had murdered his father and Princess Helena and, paranoid over the forged will he believed was real, killed Hope to protect his inheritance.

The final section shifts to a year later. Eden, Renee, and Ruby are living in Los Angeles.

Eden has become Ruby’s guardian of sorts and is financially strained due to a writers’ strike. Renee is haunted by her past, and Ruby, though determined to enter the entertainment world, remains fragile.

Aria, Eden’s frenemy and TV producer peer, returns, proposing a new show centered on Bianca, Carmela’s daughter, who now runs a gossip account called Shady Di. Aria manipulates Eden with footage of her forging Birdie’s will.

Aria needs Eden’s help to manufacture drama in the new show. Despite her personal growth and new responsibilities, Eden agrees—hinting that her ties to the corrupt world of reality television may never be fully severed.

The story ends with the suggestion that even tragedy cannot completely undo the seductive power of spectacle.

Characters

Eden Bennett

Eden Bennett stands as the dominant force in The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey, a woman whose life has been shaped by both ambition and abandonment. As a reality TV showrunner for Garden State Goddesses, Eden has transitioned from a would-be documentarian with a passion for truth to a ruthless orchestrator of drama.

Her ability to manipulate people, stories, and emotions is unmatched, and she weaponizes this talent not only to climb the industry ranks but to exert control over others—especially her cousin Hope. Eden’s relationship with Hope is fraught with contradictions: she rescues Hope from a stifling religious cult, yet exploits her trauma for entertainment.

This tension lies at the heart of Eden’s character. She is both savior and puppeteer, protector and predator.

Her emotional coldness is a defense mechanism; buried beneath it are layers of guilt, grief, and suppressed empathy, which occasionally surface in her interactions with Ruby and Renee after Hope’s death. Despite her attempts at redemption, Eden remains ensnared in the very world she claims to critique.

Her inability to fully break free from reality TV’s gravitational pull—even when faced with the consequences of her own decisions—renders her a tragic figure: brilliant but broken, sharp but deeply scarred.

Hope Fontana (née Bennett)

Hope is the emotional and moral epicenter of The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey—a woman trying to rebuild herself after surviving a life of religious extremism and psychological control. Introduced during a surreal wedding to Leo Fontana, Hope initially appears as a fragile and enigmatic outsider.

Her history with Brother God, the church led by her and Eden’s fathers, informs much of her internal conflict. Haunted by past trauma and the loss of familial ties, Hope enters the glittering chaos of reality TV like a ghost—present, yet often disconnected.

Her musical talents and quiet strength win over some, like Ruby and Renee, but others—like Carmela and Pierre—perceive her vulnerability as a threat. Hope’s relationship with Renee reveals a more passionate, yet equally complicated side: she is capable of intense intimacy but remains guarded, weighed down by secrets.

Her final days are marked by emotional disintegration, culminating in a shocking collapse that leads to accusations of parricide. Whether victim, manipulator, or martyr, Hope is a vessel for the novel’s most haunting questions about faith, identity, and the thin line between reinvention and erasure.

Her presence continues to shape the lives of those she left behind, long after her death.

Renee

Renee is one of the more emotionally nuanced and conflicted characters in The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey. A single mother, bisexual, and cast member of Garden State Goddesses, she straddles multiple identities with both charm and contradiction.

Renee initially appears to be a voice of reason within the show’s toxic ecosystem, forming a gentle and secretive relationship with Hope. However, her vulnerabilities soon unravel—especially when her daughter Ruby debuts a painfully autobiographical song that exposes Renee’s emotional absence.

Her affair with Hope, while tender and deeply felt, also reveals her immaturity and escapism. Renee wants to be a better mother and partner but is constantly derailed by her own insecurities and impulsiveness.

After Hope’s death, Renee becomes one of the few characters who seeks genuine accountability. Her breakdowns and confrontations suggest a soul on the brink, but also one striving for healing.

She represents the novel’s tension between desire and responsibility, spectacle and sincerity. Ultimately, Renee’s grief becomes transformative, pushing her to reassess her priorities, even as she remains tethered to the trauma that unfolded on camera.

Carmela

Carmela, the self-anointed queen bee of Garden State Goddesses, embodies the aggressive, performative toxicity that defines much of The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey. Regal, manipulative, and viciously insecure, she is both a caricature and a deeply damaged woman.

Carmela sees Hope as a threat from the moment she enters Shady Pond, and much of her behavior—mockery, sabotage, gaslighting—stems from this defensive posturing. Her affair with Leo, which stretches over a decade, further complicates the web of betrayals that drive the plot.

Though Carmela’s power appears unshakeable, her grip is fueled by fear and jealousy. Her role in the events leading up to Hope’s death is ambiguous, shrouded in speculation and accusation.

Leo claims she poisoned Hope, yet this may be projection or paranoia. What’s certain is that Carmela’s veneer of control ultimately crumbles—first emotionally, then physically, when she is stabbed by Leo at her own salon’s anniversary party.

Her downfall is both grotesque and symbolic, a final performance in a life built on them. She is both villain and victim, a tragic reminder of what happens when power becomes a mask for pain.

Leo Fontana

Leo Fontana is a morally ambivalent figure in The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey—charming on the surface, but ultimately passive and complicit in the dysfunction around him. As Hope’s husband, he initially seems supportive, even liberal-minded—he condones her affair with Renee and positions himself as a modern man unfazed by traditional boundaries.

But this permissiveness masks deeper selfishness and cowardice. Leo’s decade-long affair with Carmela betrays not just Hope, but the pretense of sincerity he tries to maintain.

His refusal to allow Hope an autopsy after her death, citing religious reasons, is telling: he invokes faith only when it suits him. His unraveling culminates in a drunken, public accusation and physical assault on Carmela, followed by his execution at the hands of his brother, Dino.

Leo’s arc underscores the novel’s themes of duplicity, privilege, and emotional vacancy. He’s neither hero nor full villain—just another broken person who underestimated the damage of secrets and underestimated Hope’s emotional gravity.

Birdie

Birdie is one of the novel’s most flamboyant and tragic characters—a woman trapped between theatrical excess and deep emotional fragility. Owner of the palatial Château Blanche and mother to Pierre, she hosts the infamous New Beginnings party and later invites the cast to Rhode Island.

Birdie plays maternal fairy godmother to Hope, gifting her a guitar and lavishing her with affection. But her sincerity is questionable: Birdie’s moments of generosity are often overshadowed by drunken outbursts, exaggerated affectations, and performative compassion.

Her sobriety is more performance than progress, and her motivations for including Hope in her will become suspect following Hope’s death. Birdie may not be a murderer, but she is an enabler of toxicity, especially when it comes to Pierre.

Her dramatic fainting spells and shifting personas highlight her detachment from reality, reinforcing the show’s themes of identity-as-performance. By the end, Birdie is sidelined, a hollow relic of the spectacle she once dominated.

Pierre

Pierre is the undisputed antagonist of The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey—a sociopath cloaked in designer clothes and irony-laced charm. From his snide remarks to his obsession with control, Pierre radiates menace.

He resents Hope from the moment she arrives, and his hostility masks far more sinister intentions. Ultimately revealed to be the murderer of not only Hope, but also his own father and Princess Helena, Pierre’s motivations stem from greed, jealousy, and an unflinching desire to protect his inheritance.

His behavior is erratic and unhinged, veering between passive-aggressive jabs and open aggression. When Eden and Renee confront him, Pierre panics and unravels, inadvertently confirming his guilt.

His downfall—arrested at the airport with drugs, a fake ID, and a burner phone—is both fitting and anticlimactic. Pierre is the embodiment of unchecked privilege and moral decay, a reminder that beneath the gloss of wealth and celebrity often lies something rotten.

Ruby

Ruby is the novel’s silent storm—young, musically gifted, and emotionally wounded. Daughter of Renee, she exists on the margins of the adult drama for much of the novel, but ultimately delivers its most searing moment: a song about maternal neglect that forces everyone to reckon with their failures.

Ruby’s performance at the Broke Not Broken gala is both a triumph and a cry for help. Her song exposes not only Renee’s emotional absence but also the corrosive impact of the adult world on a child seeking love and security.

Ruby’s relationship with Hope is significant—she sees in Hope both a mentor and a kindred spirit. After Hope’s death, Ruby is sent away by Renee in a desperate act of damage control.

Yet she returns a year later, determined to pursue her dreams despite the wreckage. Ruby represents the future—a generation shaped by trauma but not defined by it.

Her resilience and talent offer a rare glimmer of hope in a world built on spectacle and self-destruction.

Themes

Exploitation and Performance

In The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey, the landscape of reality television becomes a breeding ground for manipulation, performance, and exploitation. At the center of this theme is Eden, a woman whose career hinges on engineering emotional spectacle.

Once motivated by documentary truth, her work now relies on exploiting people’s pain, secrets, and emotional volatility for ratings. Her decision to cast her estranged cousin Hope is emblematic of how far she’s come from authentic storytelling—turning her cousin’s traumatic past into content and treating her as an instrument to serve the show’s narrative rather than as family.

The manufactured nature of Garden State Goddesses underscores how reality TV creates artificial dynamics and pressures real people to become exaggerated versions of themselves. Hope is expected to perform vulnerability, charisma, and conflict on demand, all while navigating emotional trauma and profound displacement.

Even Renee and Birdie, older and more experienced cast members, participate in this transactional theater, with intimacy and affection often revealed to be strategic rather than sincere. The lines between sincerity and performance are so blurred that characters lose track of what is authentic, and this confusion often becomes weaponized.

The audience—both viewers of the show and readers of the novel—witness characters suffer real emotional harm under the pretense of entertainment. The ultimate cost of this exploitation is not only public disgrace or failed relationships, but death, addiction, and psychological collapse.

The entire ecosystem thrives on performance, but the consequences are all too real, particularly for those like Hope who lack the armor or cynicism required to survive in such a performative world.

Trauma, Repression, and the Aftermath of Abuse

Hope’s character arc is fundamentally shaped by the haunting presence of childhood trauma and the psychological scars left by growing up in a repressive religious cult. Her withdrawal, cryptic behavior, and moments of emotional fragility are not signs of weakness but reflections of her efforts to navigate a life still dominated by fear, shame, and unresolved grief.

The novel consistently underscores how trauma distorts identity—Hope’s reluctance to share details about her past is interpreted as evasiveness or deceit by those around her, particularly Carmela, when in truth it is an instinctive act of self-preservation. Her behavior becomes even more ambiguous when the narrative hints at her participation in or proximity to a devastating crime—the arson that killed her parents—raising questions about whether she is a survivor, a perpetrator, or both.

Characters like Renee and Eden are also implicated in cycles of trauma, albeit in different forms. Renee is emotionally distant from her daughter and uses Hope as a distraction from her failings, while Eden’s hardened emotional detachment is the result of years in an industry that punishes vulnerability.

Even Birdie’s alcoholism and Pierre’s sociopathy can be read as distorted responses to unspoken generational wounds. What emerges is a portrait of trauma that is not linear or redemptive—it does not always lead to healing, understanding, or justice.

Instead, the aftermath is chaotic and often unresolved, with betrayal, death, and suspicion replacing reconciliation. The novel refuses to sanitize the effects of trauma, making it clear that unresolved pain, when ignored or commodified, can become dangerous and even deadly.

Power, Class, and Social Hierarchy

The social fabric of Shady Pond and the Garden State Goddesses cast is one defined by stark class distinctions and performative power. Hope, coming from a modest background and religious isolation, is immediately positioned at the bottom of this hierarchy despite her new marriage into the wealthy Fontana family.

Her unfamiliarity with luxury goods, social etiquette, and cutthroat interpersonal politics renders her both visible and invisible—visible as a novelty, invisible as a true participant in the elite circle. Characters like Carmela and Pierre actively police these boundaries, using sarcasm, humiliation, and microaggressions to remind Hope of her outsider status.

The constant pressure to assimilate—whether through Instagram aesthetics, fashionable choices, or reality TV confessionals—becomes a form of class violence that demands emotional and psychological conformity. Hope’s moments of resistance, such as choosing her own drinks or questioning her portrayal, are immediately dismissed or punished.

Meanwhile, wealth functions as both shield and sword. Characters like Birdie can absolve their instability with lavish gifts or theatrical declarations, while Leo’s secrets and betrayals are obscured by his economic privilege.

Even Eden, who ostensibly worked her way up, depends on the patronage and networks of this elite world to maintain her status. The show thrives on these class dynamics, using the spectacle of newcomers attempting to navigate wealth as a narrative engine.

The entire structure privileges those who can afford to be careless with their reputations and cruel with their power. In this way, the novel critiques the illusion of meritocracy, revealing a society where power is inherited, protected, and ruthlessly enforced.

Identity, Reinvention, and the Limits of Transformation

Much of the novel hinges on the possibility—and limits—of personal reinvention. Hope is introduced at the precipice of a new life, supposedly leaving behind the trauma of her upbringing and beginning a glamorous chapter as Leo Fontana’s wife.

However, her attempts at transformation are continuously undermined by the unresolved realities of her past and the unforgiving gaze of those around her. Her new identity, constructed for both her marriage and the show, requires not just surface changes but an emotional erasure that she cannot commit to.

Similarly, Eden tries to refashion herself from a manipulative producer to a maternal figure, especially as she assumes care for Ruby in the final chapters. Yet this reinvention remains tenuous, constantly tested by her complicity in the exploitative mechanisms of reality television.

Even Renee, attempting to redeem herself after neglecting her daughter and engaging in a morally fraught affair, struggles to escape the identity of someone broken and haunted. The tension lies in how much change is possible when the structures surrounding a person—family, fame, trauma—resist transformation.

Reinvention in the novel often comes at a cost: characters may gain a new title or role, but they do so by compromising, forgetting, or betraying some part of themselves. The ending, where Eden is once again drawn into Aria’s machinations, suggests that identity in this world is less about growth and more about adaptation to constant performance.

The novel paints a cynical yet realistic picture of transformation as a loop rather than a line—one that demands sacrifice without necessarily promising resolution or redemption.

Secrecy, Betrayal, and Surveillance

Secrets are currency in The Really Dead Wives of New Jersey, and betrayal is the natural consequence of their exposure. Nearly every relationship in the novel is marked by hidden truths, concealed affairs, or past transgressions waiting to be weaponized.

From Eden’s hidden manipulation of the will to Carmela’s decade-long affair with Leo, the characters operate within a dense web of lies that are inevitably revealed in the most public and damaging ways. Hope’s entire presence on the show is one giant secret unraveling—her background, her trauma, her affair with Renee, her pregnancy, and ultimately her parents’ deaths.

The reality show format amplifies this theme, as surveillance is not just literal through cameras, but metaphorical, with cast members constantly watching, judging, and documenting one another. Confessionals, voice memos, and leaked social media posts become the means through which secrets are both confessed and exploited.

Even the novel’s climactic confrontations are shaped by surveillance—Pierre’s downfall is precipitated not by a legal confession, but by Eden’s covert recording. The show’s ethos—that nothing is off-limits—seeps into personal boundaries, encouraging betrayal as a form of emotional spectacle.

Trust is nearly impossible in such an environment; even acts of intimacy are filtered through suspicion. This culture of surveillance erodes any chance of sincere connection, reducing relationships to strategic alliances.

Hope’s demise is the ultimate casualty of this ecosystem—targeted not just by individuals, but by a collective willingness to sacrifice privacy, safety, and loyalty for dramatic payoff. The novel suggests that in a world built on secrets, survival often depends on betrayal.