The Women of Arlington Hall Summary, Characters and Themes

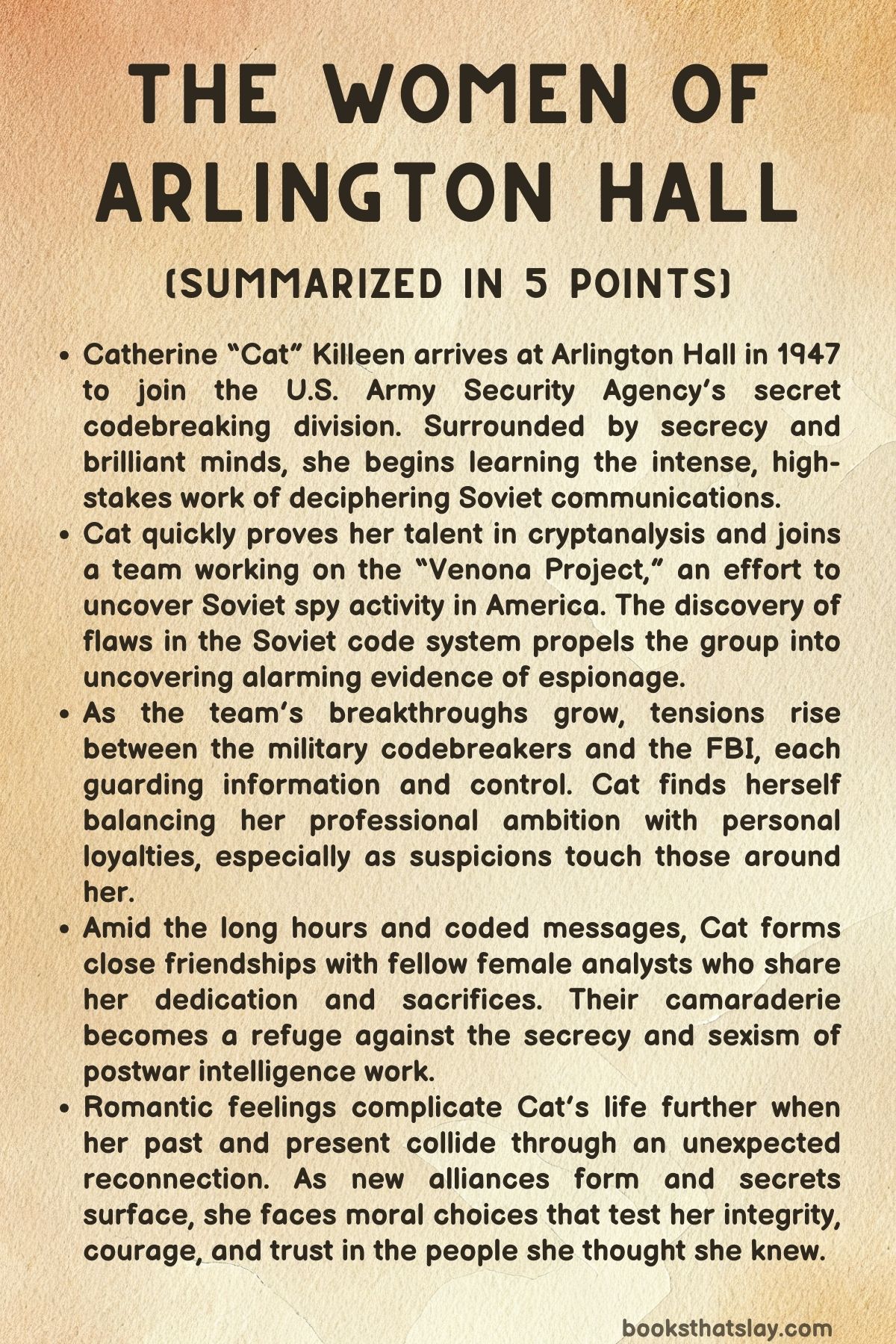

The Women of Arlington Hall by Jane Healey is a historical novel that highlights the unsung women who worked behind the scenes of America’s most secret intelligence operations in the aftermath of World War II. Through the eyes of Catherine “Cat” Killeen, the story offers a detailed look into life at Arlington Hall, the nerve center of U.S. cryptanalysis during the early Cold War.

Blending real history with fiction, the novel explores themes of secrecy, patriotism, and gender in intelligence work, portraying the women who helped unravel Soviet codes and uncover atomic espionage while navigating friendship, romance, and the heavy burden of classified duty.

Summary

In the fall of 1947, Catherine “Cat” Killeen arrives at Arlington Hall in Virginia to begin her work with the U. S. Army Security Agency. Uncertain yet determined, she endures an awkward first day that includes a mix-up at the gate and an embarrassing scuffle with her luggage.

Orientation supervisor Margaret Sherwood steps in to help, guiding her through the early bureaucratic hurdles and even helping her find housing when a paperwork error leaves her stranded.

During the mandatory orientation, Cat meets Effie LeBlanc, a cheerful recruit from New Orleans, and a dozen other young women who are introduced to the seriousness of their new roles. Each must sign strict loyalty and secrecy oaths that forbid them from ever discussing their work—even with family.

The gravity of these oaths unsettles Cat, who realizes she has committed to something far beyond the ordinary.

Cat’s skills quickly draw attention. A former professor had recommended her for her outstanding mathematical and linguistic abilities.

During her aptitude test, she impresses Margaret with her crossword-solving speed, which is seen as an indicator of strong codebreaking potential. Yet her background check reveals complications—her father’s Irish birth and her uncle Peter Walker’s membership in the Communist Party USA.

Though cleared to work, Cat is warned this could return to haunt her.

Assigned to Building B, Cat learns her department, the Russian Section—disguised as “Special Problems”—is responsible for deciphering Soviet telegrams intercepted during the war. Thousands of encrypted messages fill filing cabinets, and their mission is to break Soviet codes to expose espionage networks operating within the United States.

Her supervisor, Gene Grady, and other veterans of the section explain that the Soviets’ encryption system, known as the one-time pad, was believed to be unbreakable. However, minor errors by the Soviets during wartime had made breakthroughs possible, sparking a top-secret effort now known as the Venona Project.

Cat soon meets Meredith Gardner, the brilliant cryptanalyst whose insights have already cracked fragments of the Soviet system. His discoveries—that Soviet agents infiltrated the Manhattan Project—shock the entire department.

The realization that spies may have passed atomic secrets to the USSR gives their tedious, coded work a deadly urgency.

As Cat adjusts to long hours of cryptanalysis, she develops friendships with Effie, Dale Motlow, Gia Manzo, and Rosemary Biddle, finding solidarity in shared exhaustion and secrecy. Their camaraderie offers rare moments of laughter amid the strain.

She also crosses paths with Jonathan Dardis, a former Harvard classmate and friendly rival who now works for the FBI. Their playful banter rekindles old sparks, though both understand that romance between government workers is fraught with risk.

Catherine’s dedication earns her a place on a team assembling a master reference of Soviet code names and their real-world counterparts. Late one evening, she discovers a clue referencing a spy codenamed “Liberal” and a wife named Ethel.

This discovery hints at a spy couple and captures the attention of her supervisors, signaling Cat’s growing influence on the project.

Soon, her professional and personal worlds collide. Jonathan confides that his FBI work is tied to her department’s decryptions.

He mentions Elizabeth Bentley, a defector who revealed vast Soviet spy networks within the U. S. —a revelation that connects directly to the Venona messages. Catherine, alarmed by his openness, warns him of the danger of discussing classified work.

Despite their differences, mutual trust and affection deepen between them.

In early 1948, new breakthroughs from decoded Soviet cables confirm that Soviet spies infiltrated America’s atomic research. Director J.

Edgar Hoover himself visits Arlington Hall, praising their achievements but imposing strict secrecy, forbidding the Venona decrypts from being used in court. The FBI begins working directly with the Venona team, pairing Catherine and Meredith with Bob Lamphere and Jonathan Dardis.

This partnership marks the beginning of active collaboration between cryptanalysts and counterintelligence agents.

As the year progresses, Catherine’s bond with Jonathan strengthens, culminating in a tender farewell before his transfer to London. Their final night together at the Cairo Hotel—dancing in the snow outside under city lights—becomes an enduring memory for Catherine.

Eighteen months later, in 1949, Catherine continues her work as Venona’s breakthroughs multiply. She shares an apartment with Effie and Gia and maintains friendships that have become her chosen family.

When anti-communist fervor surges across the country, her past resurfaces—her uncle Peter’s Communist ties again draw scrutiny. Margaret warns her that suspicion could jeopardize her career.

Meanwhile, Bob Lamphere announces that the Soviets have successfully tested an atomic bomb, confirming espionage had indeed accelerated their nuclear development.

Catherine’s team faces mounting pressure to uncover the spies responsible. Through persistence, they help identify a British physicist, Klaus Fuchs, as a key Soviet source.

Fuchs’s confession implicates others, unraveling a network that stretches from Los Alamos to Washington, D. C.

Even as Catherine wrestles with fatigue and doubt, her intellectual resilience and moral conviction sustain her.

Soon, she becomes entangled in another crisis. British intelligence officers Lindsay Philmore and Ron McAllister falsely accuse her of having ties to her uncle’s espionage activities.

Desperate to clear her name, Catherine secretly meets Peter Walker in New York. Their emotional encounter reveals painful family history—his remorse over betraying both country and family—and his resolve to help her prove her innocence.

When Peter introduces her to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Catherine suddenly recognizes their names from intercepted Venona messages. She suspects Julius may be “Liberal,” the spy leader mentioned months earlier.

The next day, Peter disappears, fleeing federal pursuit. Catherine is interrogated by the FBI but remains steadfast, offering information about the Rosenbergs and her uncle’s admissions.

Gia arrives to support her, and Jonathan—suspended for aiding her—joins her in New York, where they finally confess their love. A package soon arrives from Peter containing a notarized letter and photographs implicating several spies, including Klaus Fuchs, the Rosenbergs, and others.

This evidence clears Catherine and helps the FBI confirm crucial links within the Soviet atomic ring.

Catherine returns to Arlington Hall, where Meredith apologizes for doubting her. FBI agents arrest Philmore’s associate Weissman, while Philmore and McAllister defect to the Soviet Union.

As arrests of real-world spies follow—Harry Gold, David Greenglass, and finally the Rosenbergs—Catherine and her colleagues watch history unfold, their once-secret work now echoing across headlines.

By 1950, Catherine’s personal and professional lives reach a turning point. Despite Jonathan’s reassignment to an isolated post in Texas, their bond endures through letters.

During a weekend getaway at Rosemary’s Delaware beach house, Jonathan appears unexpectedly, having traveled cross-country to see her. Declaring he is done waiting, he tells her he wants to build a future together, no matter the cost.

Catherine accepts, closing the novel on a hopeful note as they drive away, ready to start a life beyond secrecy.

The Women of Arlington Hall closes with the author’s note acknowledging how the story blends fiction with real history. The Venona Project, Meredith Gardner, and many events depicted were real.

Jane Healey’s novel pays tribute to the forgotten women cryptanalysts whose quiet brilliance helped shape the course of the Cold War.

Characters

Catherine “Cat” Killeen

Catherine Killeen stands as the central figure of The Women of Arlington Hall, embodying the tension between individual ambition and societal expectation in postwar America. Intelligent, determined, and deeply introspective, Cat’s journey begins with nervous optimism as she steps into the secretive world of cryptanalysis.

Her mathematical brilliance and linguistic talent quickly establish her as a natural codebreaker, yet beneath her professionalism lies a woman haunted by personal loss—the death of her brother Richie and her mother’s early passing. Her identity is further complicated by her Jewish heritage, Irish Catholic upbringing, and her Communist uncle, Peter Walker, all of which reflect America’s tangled web of identity and suspicion during the early Cold War.

Cat’s relationships—whether with her vivacious roommate Effie, the strict but caring Margaret, or the complicated Jonathan Dardis—reveal her struggle to balance emotion and duty. Through her resilience, moral conviction, and intellectual growth, Cat evolves from a timid newcomer to a confident, morally grounded woman who shapes her own destiny amid political paranoia and gendered constraint.

Jonathan Dardis

Jonathan Dardis, Cat’s onetime academic rival and eventual love interest, represents the charming yet conflicted face of Cold War masculinity. As an FBI agent, he operates at the intersection of law enforcement and espionage, embodying both patriotism and bureaucratic rigidity.

His flirtatious wit and boyish confidence often mask his own insecurities—particularly his moral discomfort with the secrecy and manipulation demanded by his profession. Jonathan’s relationship with Cat reveals his depth: beneath the teasing lies a genuine admiration for her intellect and courage.

Their romantic arc—from rivalry to companionship—illustrates the emotional cost of living within a system that values loyalty over humanity. His transfer to London and later reassignment to El Paso symbolize both exile and renewal, as he ultimately chooses love and integrity over ambition.

Meredith Gardner

Meredith Gardner, the brilliant but eccentric cryptanalyst leading the Venona Project, is portrayed as a complex mix of genius and frailty. His obsessive dedication to uncovering Soviet espionage elevates him to near-mythic status among his colleagues, yet his human vulnerabilities—his pride, insecurity, and eventual humility—make him one of the novel’s most nuanced figures.

Gardner’s early dismissiveness toward Cat’s abilities gives way to mentorship and respect, mirroring the broader transformation of a male-dominated field reluctantly recognizing female intellect. His uneasy alliance with the FBI and his clashes with J.

Edgar Hoover highlight the moral ambiguities of wartime intelligence work: the pursuit of truth often required sacrificing transparency and ethics. In Gardner, Jane Healey crafts a portrait of brilliance both burdened and redeemed by conscience.

Bob Lamphere

FBI Agent Bob Lamphere serves as the moral backbone of the intelligence apparatus within The Women of Arlington Hall. Practical, diligent, and deeply patriotic, Lamphere is both ally and skeptic within the Venona team.

His collaboration with Gardner and Cat bridges the gap between cryptanalysis and counterintelligence, though it also exposes the growing rift between scientific inquiry and political zeal. Unlike the more volatile Hoover, Lamphere is grounded in pragmatism and a sense of justice.

His relationship with Catherine is one of professional respect, and he emerges as a steady force amid chaos—a man disillusioned by bureaucracy but still committed to uncovering the truth. His exhaustion and frustration during the Soviet atomic test crisis reveal a humanity that offsets the institutional paranoia surrounding him.

Effie LeBlanc

Effie LeBlanc, the vivacious and kind-hearted woman from New Orleans, provides warmth and levity in contrast to the novel’s intellectual intensity. Her charm and humor mask her own struggles with loneliness and fatigue, but she remains a constant source of friendship and optimism for Cat.

Effie represents the ordinary women who, thrust into extraordinary circumstances, found strength and purpose in service to something larger than themselves. Her easy sociability, Southern charm, and empathetic nature make her the emotional glue of the Arlington Hall community.

By encouraging Cat to engage socially and emotionally, Effie helps her navigate both the professional demands and emotional turbulence of espionage life.

Margaret Sherwood

Margaret Sherwood is the strict orientation supervisor who first welcomes Cat into Arlington Hall. Stern but ultimately compassionate, Margaret’s character evolves from a bureaucratic gatekeeper to a deeply human figure hiding personal vulnerabilities.

Her revelation as Rosemary’s secret partner introduces a powerful subplot about forbidden love and the fear of exposure in an era of moral and political policing. Margaret’s professionalism, attention to detail, and quiet courage mirror the disciplined yet compassionate leadership that many women exercised behind the scenes during this period.

Through her, Healey examines how secrecy extends beyond national defense—it shapes personal identity and love itself.

Rosemary Biddle

Rosemary Biddle is Cat’s colleague and confidante, whose personal story of escaping an arranged marriage and navigating a secret relationship with Margaret underscores the novel’s theme of hidden truths. Gentle, thoughtful, and wise, she becomes a moral anchor for the group, offering Cat a sense of sisterhood and perspective.

Rosemary’s dual existence—professional precision by day, secret love by night—reflects the suffocating conformity of postwar America and the quiet rebellion of those who dared to live authentically. Her empathy and emotional intelligence contrast beautifully with the analytical world of cryptography, grounding the narrative in human tenderness.

Gia Manzo

Gia Manzo is one of the more colorful members of the Venona team—bold, outspoken, and brimming with life. Her sharp tongue and playful attitude conceal a deep intellect and loyalty to her friends.

Through her, the novel captures the camaraderie and occasional chaos of life at Arlington Hall. Gia’s flirtation with the eccentric Cecil Peterson adds humor, but it also hints at how even the most grounded individuals sought connection amid the isolation of secrecy.

She represents the free spirit within an institution that prized obedience, reminding readers that rebellion can exist even within the most regulated spaces.

Cecil Peterson

Cecil Peterson, the odd but gifted codebreaker, embodies the archetype of the eccentric genius. His quirks—obsession with UFOs, unconventional dress habits, and unfiltered honesty—make him both comic relief and symbol of intellectual freedom.

Beneath his oddities lies a profound brilliance that contributes to the team’s success. Cecil’s friendship and possible romantic connection with Gia humanize him, transforming what could have been a caricature into a portrait of individuality surviving within a rigid system.

He reflects the novel’s recurring message: brilliance often walks hand-in-hand with nonconformity.

Peter Walker

Peter Walker, Catherine’s estranged uncle and a Communist physicist, serves as the ideological mirror to the novel’s central moral dilemmas. His decision to share atomic secrets with the Soviets stems not from treachery but from idealistic conviction—the belief that no nation should wield unilateral control over nuclear power.

Peter’s intelligence and regret, particularly regarding his estrangement from Catherine’s mother, make him a tragic figure caught between conscience and consequence. His relationship with Catherine transforms from suspicion to mutual respect, ultimately aiding her redemption and propelling the uncovering of the real spies.

Walker’s character embodies the gray moral space of the Cold War, where patriotism and betrayal often blurred.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

The Rosenbergs, introduced late in the novel, serve as historical anchors within Healey’s fictional narrative. Their presence blurs the boundary between fiction and fact, connecting Catherine’s personal struggle to real-world events.

Julius, identified as “Liberal,” and Ethel, his devoted wife, are portrayed not as one-dimensional villains but as complex individuals driven by ideology and loyalty. Their ultimate downfall represents both the triumph and tragedy of American justice during the Red Scare era—a moment when the search for truth was often clouded by fear.

Through their depiction, Healey forces readers to confront the uneasy reality that patriotism and treachery can wear similar faces.

Brendan

Brendan, the British liaison introduced near the novel’s conclusion, symbolizes hope and new beginnings. His presence marks the potential for Catherine to move beyond loss, espionage, and heartbreak toward a more balanced life.

His gentle demeanor and open curiosity contrast with Jonathan’s intensity, suggesting a future built on understanding rather than secrecy. Brendan’s arrival reinforces the cyclical nature of Catherine’s journey—after years of cryptic messages and hidden loyalties, she finally encounters a man who represents transparency and possibility.

Themes

Women and Work in Postwar America

In The Women of Arlington Hall, the narrative vividly portrays the transformation of women’s roles in the immediate postwar era, a time when societal expectations began to shift yet remained deeply rooted in traditional norms. The women working at Arlington Hall, including Catherine Killeen, Effie LeBlanc, Rosemary Biddle, and others, represent an entire generation caught between the independence they achieved during wartime service and the societal pressure to return to domestic life.

Through their lives, the novel explores the complexity of this transition — how these women, armed with intellect and ambition, sought meaning and identity in a world reluctant to grant them full professional legitimacy. Their work in codebreaking, one of the most intellectually demanding and secretive wartime roles, becomes a symbol of silent empowerment.

They contribute to national security, yet the confidentiality of their work prevents public recognition. This anonymity adds a layer of irony — they are essential, yet invisible.

The novel also explores camaraderie among these women, their friendships functioning as both emotional sustenance and quiet rebellion against gendered isolation. Jane Healey captures not only the intellectual fulfillment they find in their work but also the exhaustion, loneliness, and occasional disillusionment that accompany it.

The women of Arlington Hall stand as early pioneers of a modern female professional identity — one defined by intellect, autonomy, and the willingness to challenge a system built to limit them.

Patriotism, Loyalty, and Moral Ambiguity

The book examines patriotism not as blind allegiance, but as a moral struggle tested by secrecy, politics, and personal conviction. Catherine’s work as a cryptanalyst demands absolute loyalty to her country, reinforced through oaths of silence and the ever-present threat of espionage prosecution.

Yet, through her connection to her uncle Peter Walker, a physicist and Communist sympathizer, the novel exposes the gray areas within patriotic duty. Peter’s justification for sharing atomic secrets — to prevent a monopoly of destructive power — forces both Catherine and the reader to question the ethics of absolute secrecy and the political manipulation of loyalty during the early Cold War.

The Venona Project itself, while rooted in the pursuit of truth and national protection, becomes a mechanism for paranoia and witch hunts as McCarthyism takes hold. Catherine’s own interrogation and near-ruin at the hands of bureaucratic suspicion highlight how fear corrodes justice and morality.

The novel’s moral depth lies in its refusal to portray patriotism as simple heroism; instead, it presents it as a constant negotiation between conscience and duty. The characters’ choices reflect the tension between truth and propaganda, belief and coercion — revealing that in times of political hysteria, patriotism can become both shield and weapon.

Secrecy, Trust, and Isolation

Secrecy functions as both the architecture and the emotional weight of The Women of Arlington Hall. The novel is built around a culture of concealment — classified messages, hidden identities, and forbidden conversations — and this secrecy extends beyond the professional into the personal lives of the characters.

Catherine’s inability to share her work with her family isolates her, and even among colleagues, layers of classification restrict openness. This environment breeds not only suspicion but also an emotional distance that threatens intimacy and mental well-being.

Trust becomes a precious but fragile commodity. The dynamic between Catherine and Jonathan Dardis exemplifies this tension: their affection grows in the shadow of professional secrecy, their relationship shaped by what cannot be said.

Similarly, Margaret and Rosemary’s concealed romantic relationship mirrors the larger secrecy of the workplace, demonstrating how private truth must often be hidden for survival. Healey uses these personal dimensions of secrecy to highlight the psychological cost of serving in a system built on distrust.

The women’s silence becomes both an act of patriotism and a form of self-erasure. The novel ultimately suggests that while secrecy is essential to intelligence work, it exacts a profound toll on the human need for honesty, connection, and understanding.

Gender, Power, and Institutional Control

The narrative exposes the subtle mechanisms through which power operates within male-dominated institutions, particularly in the military and intelligence community. Catherine’s experiences at Arlington Hall underscore the systemic challenges women faced — not only in earning respect for their intellectual contributions but also in navigating a hierarchy that constantly reminded them of their secondary status.

Meredith Gardner’s early dismissal of Catherine’s insights, later followed by his reluctant admiration, captures this gendered ambivalence. Even as women become indispensable to national security, they are often patronized, under-credited, or silenced.

The novel portrays how women like Catherine and Margaret use resilience, intellect, and solidarity to subvert institutional limitations. Yet it also acknowledges the psychological strain of existing within systems that reward compliance over creativity.

The rigid codes of behavior, the moral policing of female workers’ personal lives, and the constant scrutiny of their backgrounds reveal how gender and power intersect to maintain institutional control. By situating its female characters in the heart of Cold War intelligence, the book transforms their struggle for professional recognition into a broader commentary on autonomy and resistance within oppressive structures.

Love, Loss, and Emotional Resilience

Beneath the tension of espionage and secrecy, The Women of Arlington Hall unfolds as a deeply human story of longing and endurance. Catherine’s romantic journey — from her broken engagement to her complex relationship with Jonathan Dardis — reflects the emotional volatility of living under constant pressure.

Love in this world is fleeting, shadowed by the impermanence of wartime assignments and the ever-present risk of betrayal. Yet it is also what sustains the characters, offering moments of warmth in an otherwise cold, bureaucratic existence.

Catherine’s eventual reconciliation with vulnerability — her willingness to love despite uncertainty — becomes an act of courage parallel to her professional bravery. The motif of loss, from her mother’s death to her brother’s wartime sacrifice, deepens her emotional resilience and sense of duty.

Friendships among the women form another expression of love, one rooted in empathy and shared struggle. Through these relationships, Healey explores the idea that connection — whether romantic or platonic — becomes an act of defiance against the emotional sterility demanded by secrecy and discipline.

The novel’s closing image, of Catherine and Jonathan choosing love and freedom over career constraints, encapsulates the triumph of personal authenticity in a world that thrives on concealment and conformity.