We Do Not Part Summary, Characters and Themes

We Do Not Part by Han Kang is a haunting, lyrical exploration of trauma, memory, and human connection.

In the wake of personal and historical violence, an unnamed narrator struggles with psychological fragmentation while navigating the ghostly presence of war, grief, and artistic responsibility. The novel is structured in three movements—Bird, Night, and Flame—each representing a stage in the narrator’s emotional and existential journey. Through stark prose and poetic imagery, Han Kang examines what it means to bear witness, to survive, and to hold space for both the living and the dead.

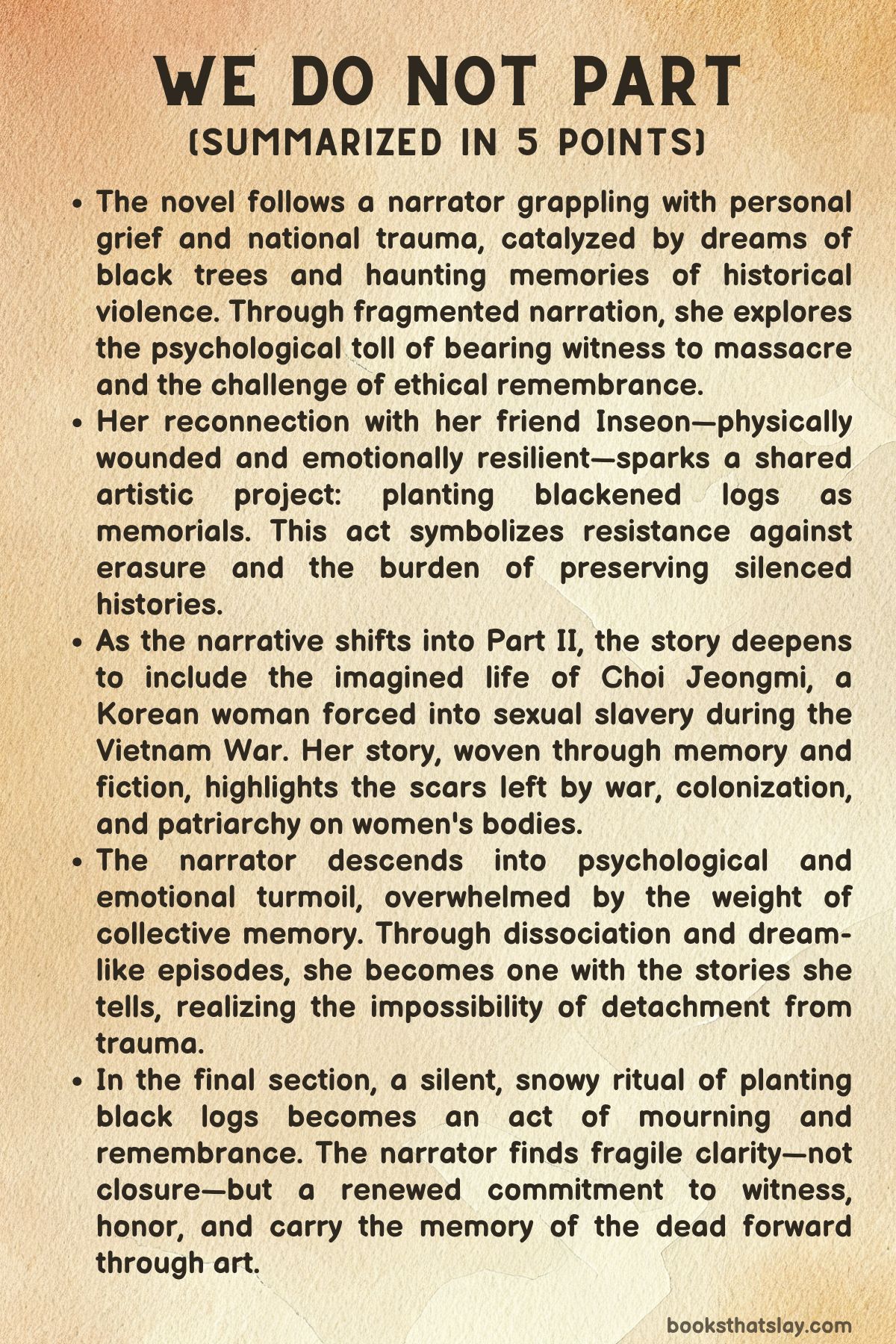

Summary

We Do Not Part unfolds in three parts—Bird, Night, and Flame—each marking a descent into and eventual emergence from grief.

At its center is an unnamed narrator, an author who has written a book on a historical massacre in the fictional city of G—, an act that leaves her emotionally and physically shattered.

The story is a layered, introspective account of trauma, artistic responsibility, and the fragile ties between people.

Part I: Bird

In Part I: Bird, the narrator is submerged in emotional and bodily collapse.

Haunted by dreams of a snowy field filled with grave-like blackened tree trunks and an encroaching sea, she embodies the toll of unprocessed trauma.

Her dreams merge with her waking state, marked by depression, disconnection, and physical ailments.

She begins writing farewell letters, cleaning her home, and confronting the echoes of the massacre that her book described.

A vision takes hold of her: planting 99 black logs in snow as a memorial.

She shares this idea with her friend Inseon, who offers land in Jeju for the project.

This collaboration becomes a quiet turning point—a suggestion that remembrance through art may offer a path forward.

Part II: Night

The second part, Night, deepens the emotional core of the novel.

The narrator learns that Inseon, a former documentarian and now a woodworker, has suffered a severe hand injury while preparing the memorial project in Jeju.

Her fingertips were reattached, but she must endure needles every few minutes to keep them alive.

This becomes a stark metaphor for the endurance required to sustain memory and identity.

The story shifts to Inseon’s background: her withdrawal from public life, her artistic solitude, and her own silent grief.

Inseon had quietly taken responsibility for the memorial when the narrator could not, sculpting logs in solitude.

Her pain becomes an extension of the narrator’s unfinished promise.

At the hospital, a quiet yet profound companionship unfolds.

The narrator becomes a witness and caregiver, surrounded by stillness and the muted rhythm of hospital life.

She is forced to confront her own failures—the ways she had abandoned the vision, the burden she unintentionally placed on Inseon.

Yet, Inseon’s calm dignity and request that the narrator complete the project stir something long-dormant.

The image of “the deep sea” emerges, symbolizing both buried trauma and the depth of emotional connection that survives despite pain and silence.

Part III: Flame

In the final section, Flame, the narrator returns to Jeju alone, carrying Inseon’s last wish.

She arrives during a snowstorm and walks through the landscape that had once existed only in her dreams: a white field, a black forest, the sea in the distance.

She finds the logs—some shaped, some waiting—half-buried in the snow.

This act of presence, of physically standing among the remnants of the vision, marks a quiet transformation.

The dream has become real, and the narrator accepts the burden not just of memory but of continuation.

There is no triumphant closure—no full healing or redemptive arc—but there is form, stillness, and a subtle affirmation.

The narrator chooses not to escape grief but to live with it, to witness and remember.

The title, We Do Not Part, underscores the enduring bonds formed through shared suffering and artistic communion.

In the end, survival is not a victory but an act of will—“to rise among the trees,” even as snow and sea threaten to erase all.

Characters

In We Do Not Part, Han Kang intricately explores the emotional and psychological journeys of her characters, particularly the unnamed narrator and Inseon, through their shared trauma, grief, and artistic endeavors.

The development of their characters is nuanced, representing not only personal experiences but also broader reflections on collective memory and historical violence.

The Narrator

The narrator, whose name remains unspoken, is a central figure who embodies the themes of trauma, memory, and the struggle for survival. At the beginning of the story, she is portrayed as deeply fractured by a past event tied to historical violence.

This trauma manifests physically in her health, with symptoms such as migraines, depression, and a profound sense of disconnection from the world. Her emotional and psychological unraveling is vividly depicted through her dreams and the deteriorating state of her daily life.

She retreats into isolation, experiencing a sense of guilt and helplessness, yet also feels a slow compulsion to reconnect with the world, particularly through her writing and artistic projects. Throughout Part I, she is shown grappling with the weight of her past and the way it intrudes upon her present, symbolized by her recurring dreams and the idea of a memorial project.

Her journey is one of slow, painful recovery, though she remains uncertain and ambivalent about confronting the full scope of her grief. By Part III, however, there is a subtle but significant shift—she finds herself confronting the work she had abandoned, standing in the snow-covered field surrounded by the memorial logs, embracing her role in the collective act of remembering.

The narrator’s final transformation is one of acceptance, where she recognizes that survival does not mean escaping the trauma but continuing to live in the shadow of it.

Inseon

Inseon is the narrator’s old friend who plays a crucial role in the unfolding of the narrative, both as a mirror to the narrator’s pain and as an individual undergoing her own personal crisis. Inseon’s backstory reveals a woman who was once a documentarian, dedicated to telling the stories of women affected by war and colonization.

This suggests a deep empathy for others’ suffering, but also a personal history of grappling with the scars of history. Her transition from film to woodworking represents a retreat from public representation into private, tactile creation—a shift that underscores her own withdrawal from the world as she processes her grief.

Inseon’s injury, where she severs her fingertips in a carpentry accident, becomes a significant metaphor for the pain and sacrifice inherent in the act of remembering. Despite her physical suffering, Inseon maintains an extraordinary calm and philosophical acceptance of her pain, which profoundly affects the narrator.

Her endurance and commitment to the memorial project, despite her own isolation and injury, contrast with the narrator’s earlier retreat from it, emphasizing Inseon’s strength and resolve. Inseon’s final request for the narrator to complete the memorial in her stead signifies a powerful act of trust and an acknowledgment of the importance of memory, even in the face of immense suffering.

Inseon represents resilience, and through her, the narrator begins to understand the necessity of engaging with the past, no matter how painful.

Themes

The Interconnection Between Personal Trauma and Collective Memory

A significant theme in We Do Not Part is the exploration of how personal trauma intersects with historical and collective memory. The narrator’s grief and psychological fragmentation are not isolated; they are deeply entwined with the violence of the past, particularly a massacre referenced in the novel, which impacts the narrator’s sense of identity and her relationship with her surroundings.

Her psychological breakdown is mirrored by the larger societal trauma, and the physical and emotional scars she bears reflect the way history seeps into the present, influencing how one understands and interacts with the world. This connection is symbolized through the recurring motif of trees buried in snow and the project to plant black logs, which becomes a ritualistic act of both remembering and confronting past atrocities.

The Power of Art as Memory and Resistance

Another prominent theme is the role of art in preserving memory, as well as its power to act as a form of resistance. Inseon, the narrator’s friend, uses her work as a documentarian and later as a woodworker, to process and channel grief.

The artistic act becomes a form of ritual—one that creates a space for grief to be witnessed and, through that witnessing, to persist. The project of planting black logs in a snowy field is both an artistic memorial and a tangible means of bearing witness to history’s violence.

This project serves as a quiet form of rebellion, not against the world, but against forgetting. It reflects the idea that art allows one to confront the unspeakable and give voice to that which otherwise remains silenced.

Resilience and the Struggle to Continue Amidst Unbearable Pain

The theme of resilience, particularly in the face of overwhelming grief and physical pain, runs throughout the novel. The physical injury of Inseon—severed fingertips that require constant painful maintenance to preserve function—becomes a metaphor for the emotional and psychological endurance needed to survive trauma.

The constant acts of care, both by Inseon and the narrator, mirror the daily, invisible work required to continue living despite a past that refuses to be forgotten. The idea of “remaining light,” as symbolized through the imagery of trees and snow, portrays resilience as an ongoing struggle—not a triumph, but a subtle and enduring act of survival.

The narrator’s decision to continue, despite her internal conflict and sorrow, highlights how survival often requires a quiet acceptance of both the beauty and the burden of life.

The Silent Bonds of Shared Grief and Connection

The novel places great emphasis on the power of shared grief and silent connection. The relationship between the narrator and Inseon is pivotal; while not overtly verbal, their bond is one of mutual understanding and unspoken support.

This theme is particularly important in Part II of the novel, where Inseon’s injury and suffering evoke a profound silence between the two women, yet this silence speaks volumes about the nature of their bond.

Inseon’s injury, which she sustains while working on the memorial project that the narrator envisioned, brings to the forefront the complex ways in which people are interconnected through shared acts of care, pain, and remembrance.

It suggests that the act of bearing witness to another’s suffering can be a powerful form of connection, transcending words and even physical presence.

The Existential Struggle to Find Meaning in the Wake of Loss

Lastly, the existential theme of seeking meaning in a world filled with loss pervades the entire narrative. The recurring images of snow, trees, and the sea all symbolize forces that are beyond human control—forces that shape the lives of the characters.

In the final part of the book, the narrator’s journey to Jeju and her decision to carry out Inseon’s project is symbolic of her existential struggle to find purpose and meaning after years of enduring loss. The memorial project, which initially seemed like a daunting task filled with emotional weight, becomes an act of reclamation.

The narrator’s eventual acceptance of her role in completing the project reflects a quiet acceptance of the ambiguity of survival, where meaning is not always clear, but the act of living itself becomes a form of testament to the persistence of life amid trauma.