Witchcraft for Wayward Girls Summary, Characters and Themes

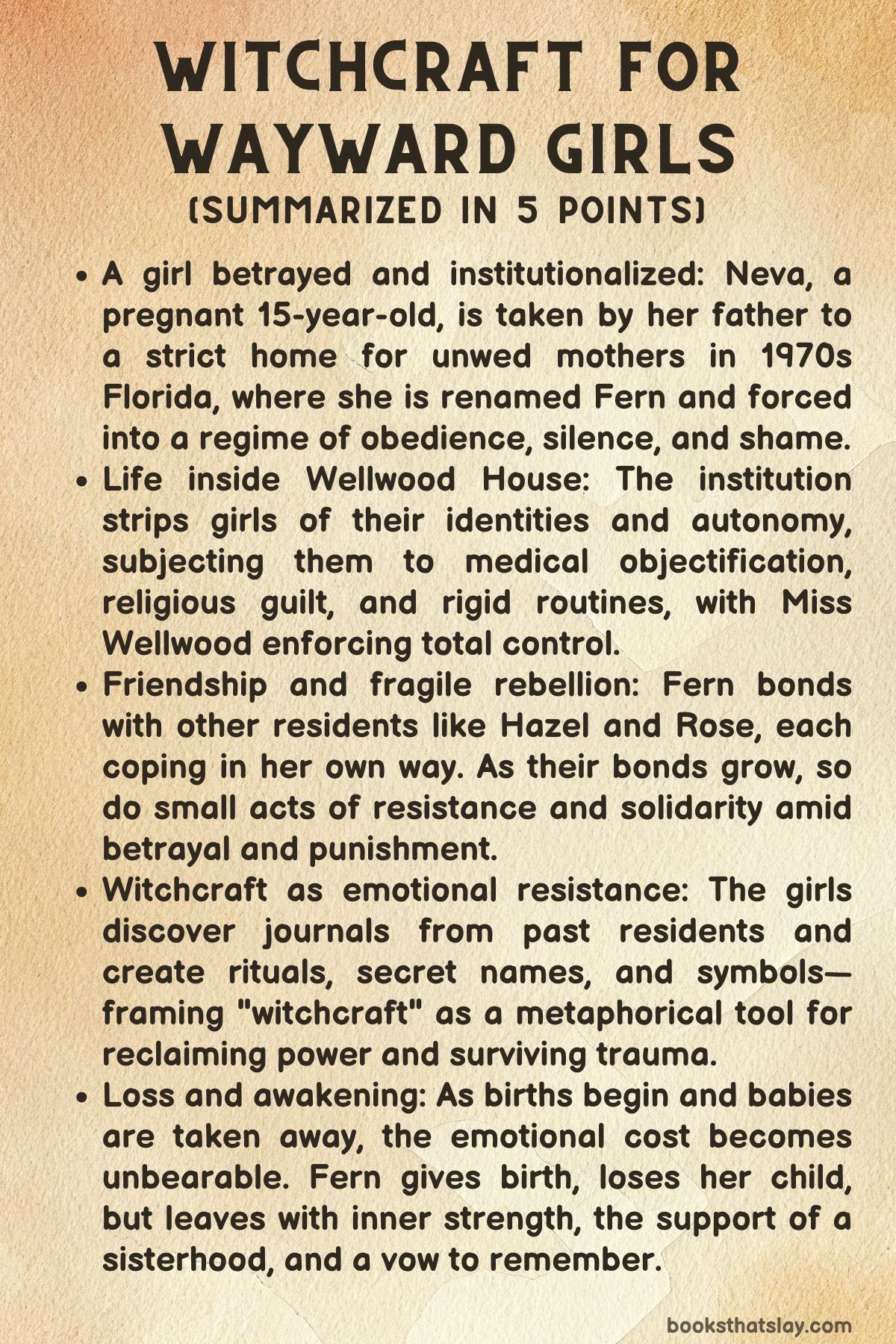

Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix explores the hidden lives of pregnant teenage girls sent away to maternity homes in the 1970s.

Set in the oppressive, religiously charged Wellwood House in Florida, the story follows 15-year-old Neva—renamed Fern—as she is forced into conformity and silence. Through themes of identity, trauma, resistance, and female solidarity, Hendrix crafts a poignant critique of patriarchal control and institutional cruelty. As the girls reclaim their voices and identities through rituals that echo witchcraft, the novel becomes a powerful tale of survival, rebellion, and transformation.

Summary

Witchcraft for Wayward Girls unfolds in a rigid maternity home during the 1970s where pregnant teenage girls are hidden away by their families to give birth in secrecy and surrender their babies.

The novel centers on 15-year-old Neva from Alabama, who is abruptly taken by her father and left at Wellwood House in Florida—a grim facility that functions more like a prison than a refuge.

Upon arrival, Neva is renamed Fern, a symbolic erasure of her identity.

The home strips all residents of personal freedom, identity, and autonomy under the guise of moral and religious correction.

At Wellwood House, girls are assigned plant names and subjected to strict routines and surveillance.

Fern struggles with the cruelty and coldness of the system, embodied by the authoritarian Miss Wellwood and the clinical, dehumanizing Dr. Vincent.

Yet in this suffocating environment, Fern slowly forms tentative bonds with other residents: the rebellious Rose, the kind and maternal Hazel, the eccentric Myrtle, and others like Daisy, Flora, and Holly.

Each girl represents a different form of resistance, trauma, or resignation.

The first half of the novel chronicles Fern’s psychological breakdown and reluctant adaptation.

The girls endure daily humiliations, invasive medical examinations, religious shame, and isolation.

The institution enforces obedience through name-stripping, censored communication, monitored routines, and fear.

Despite the bleakness, moments of connection and empathy emerge—Hazel offers Fern guidance, and Rose provides a spark of defiance that inspires others.

Gradually, Fern begins to understand the unspoken survival code of the Home and begins to push back internally, even as she outwardly complies.

The second half of the novel sees Fern and the girls transition from passive victims to active resisters.

Their emotional bonds deepen as they begin to share secrets, perform symbolic rituals, and reclaim parts of themselves.

They discover journals and items left by former residents hidden in a forgotten room, revealing that their suffering is part of a generational cycle.

These relics spark a sense of legacy and empowerment.

Framing their resistance as “witchcraft,” the girls invent ceremonies, codewords, and even “spells” to regain control over their stolen identities.

One night, they reclaim their real names in a secret naming ceremony.

Another girl, driven by fear or manipulation, betrays them, resulting in Daisy’s punishment.

But the punishment only strengthens their resolve.

They begin enacting small acts of sabotage—rearranging rooms, leaving cryptic notes—as a form of magical protest.

Through these symbolic rituals, they rewrite their pain into power.

Amid ongoing heartbreak—miscarriages, mail burnings, and forced separations—the girls cling to each other.

One of the most emotional turning points comes when they perform a vigil for Myrtle’s stillborn child, a moment of collective grief and defiant love.

Fern becomes increasingly bold, even confronting Dr. Vincent with painful questions.

She sneaks into the forbidden nursery only to find an eerie silence—no babies, just empty cribs.

As their pregnancies reach full term, each girl faces the loss of their child.

Before giving birth, they conduct intimate, whispered naming ceremonies for the unborn, an attempt to reclaim at least a piece of motherhood.

Rose’s final rebellion and Hazel’s tragic confession about abuse at home add depth and gravity to their shared trauma.

Fern’s labor is harrowing and her baby is taken immediately after birth.

Miss Wellwood delivers a final sermon about shame and forgetting, but Fern rejects the imposed narrative.

Though she leaves the Home without her baby, she carries something profound: the names, voices, and memories of the girls who endured with her—and a defiant sense of self that no institution could extinguish.

Characters

Fern (Neva)

Fern, initially introduced as Neva, is the protagonist of the story. At the beginning of the novel, she is a young, naive teenager who is suddenly thrust into a harsh and controlling environment after being sent to Wellwood House.

As her name is stripped away, Fern symbolizes the loss of identity and autonomy experienced by the girls in the institution. Despite the oppressive environment, Fern shows a growing sense of self-awareness.

Her quiet strength emerges as she bonds with the other girls and begins to resist the institution’s control. By the end of the novel, Fern’s journey represents the transformation from victimhood to empowerment, as she finds strength in unity and resilience among the girls, despite the loss she endures.

Rose

Rose is one of the first residents Fern meets at Wellwood House. Known for her rebellious nature, Rose quickly becomes a leader among the girls.

She openly mocks the rules of the institution and questions its morality, challenging the authority of Miss Wellwood. Rose’s outspoken nature contrasts with Fern’s more reserved demeanor, and it’s through Rose that Fern begins to understand the potential for resistance within the harsh confines of Wellwood House.

Rose’s character is crucial in teaching the other girls that their pain can be transformed into power. She becomes a symbol of defiance and individuality in the face of overwhelming control.

Hazel

Hazel is a more reserved and maternal figure in the group. She takes Fern under her wing, offering advice on survival in the Home and helping her navigate the oppressive structure.

Hazel’s backstory is particularly tragic, as she reveals that her pregnancy resulted from molestation by a family friend. This revelation deepens the emotional stakes of the novel, highlighting how systemic abuse is often hidden under societal structures.

Hazel’s role in the story is significant because she represents the quiet endurance of trauma and the hidden strength of those who appear the weakest. Her bond with Fern is one of the most genuine in the book, as they provide each other with support amidst the dehumanizing circumstances of their confinement.

Myrtle

Myrtle is a more eccentric and vulnerable character, known for her quirky behavior and emotional fragility. Her struggle with the institution’s control is portrayed through her vulnerability, and she becomes one of the most tragic figures in the novel.

Myrtle’s eventual miscarriage and the cold response of the institution to her loss underscore the brutal emotional repression enforced at Wellwood House. Despite her outward oddness, Myrtle’s pain resonates deeply with Fern and the other girls, illustrating the shared suffering and loss that unites them.

Her character serves as a reminder of the devastating impact of the Home on the girls’ mental and emotional well-being.

Miss Wellwood

Miss Wellwood, the authoritarian headmistress of the institution, is the embodiment of the oppressive system that governs the girls’ lives. Her cold, calculating demeanor and strict enforcement of rules create an atmosphere of fear and submission.

However, Miss Wellwood’s character also represents the blind adherence to moral and social norms that justify cruelty under the guise of religious righteousness. Her interactions with Fern and the other girls highlight the psychological manipulation used to control and diminish their sense of self.

Miss Wellwood’s character is a symbol of the institutional forces that exploit and dehumanize vulnerable individuals for the sake of control.

Dr. Vincent

Dr. Vincent represents the medical and institutional abuse the girls face at Wellwood House. As a figure of authority, he treats the girls like objects rather than individuals, conducting impersonal exams and subjecting them to humiliating procedures.

His character adds to the novel’s critique of the ways in which women’s bodies are objectified and controlled in societal systems. Dr. Vincent’s actions serve as a reminder of the cold, clinical violence inflicted on the girls, which mirrors the emotional and physical manipulation that permeates the Home.

Daisy

Daisy is another resident at Wellwood House whose tragic breakdown illustrates the psychological toll the institution takes on the girls. She is one of the first to begin cracking under the pressure of constant surveillance, medical violation, and emotional repression.

Daisy’s punishment for revealing the secret rituals conducted by the girls serves as a reminder of the severe consequences of defying the oppressive system.

Her eventual fate symbolizes the crushing impact of institutional control on mental health, as she is punished not just for her resistance, but for the vulnerability she cannot hide.

Themes

Dehumanization and Institutional Control in Patriarchal Systems

A central theme in Witchcraft for Wayward Girls is the systematic dehumanization that the female protagonists experience within the authoritarian institution of Wellwood House. The novel critiques how oppressive systems strip individuals of their personal identities, particularly those of women, to serve the larger societal narrative.

At Wellwood, the girls are subjected to rigid regulations that control every aspect of their existence, from their names to their daily routines. Fern, the protagonist, is renamed “Fern,” and all the girls are forced to surrender their individuality as they become mere numbers within the system.

Their autonomy is constantly violated, from the intense surveillance of their actions and words to the medical objectification they face during frequent, impersonal exams. This theme of institutional control is presented through the lens of a society that enforces silence, obedience, and shame, punishing any attempt to assert personal power or voice.

Emotional Repression and the Silent Struggle for Autonomy

Another major theme is the emotional repression imposed upon the girls in Wellwood House. The characters struggle with their own identities, and their emotional responses to trauma are either suppressed or ignored by the institution.

The religious and societal pressures placed on the girls add a layer of guilt and shame that fosters internalized repression. Miss Wellwood, the authoritarian figurehead, uses religious rhetoric to enforce the girls’ sense of sin, positioning them as morally flawed for their pregnancies.

Yet, beneath this oppressive surface, the girls’ emotional growth and rebellion begin to manifest.

In subtle, often small ways, they push back against the system by creating a sisterhood, developing secret rituals, and forming bonds that allow them to reclaim some measure of control over their lives.

The repression they experience gives way to a deeply rooted emotional awakening, culminating in their pursuit of personal freedom through acts of resistance.

Resistance and Reclamation of Identity through Ritual and Witchcraft

As the story progresses, the girls discover a form of resistance that draws on ritualistic practices and witchcraft. Initially, the notion of witchcraft may seem like a metaphor, but it evolves into a powerful tool for reclaiming autonomy.

Witchcraft, in the context of the novel, becomes a means of forging an alternative identity that is not dictated by the patriarchal and oppressive system they find themselves in. The girls use symbolic rituals, such as naming ceremonies, “hexes,” and the reclamation of their real names, to carve out a space for emotional expression and personal agency.

These acts of rebellion—small yet potent—allow the girls to bond over shared experiences of trauma, creating a solidarity that challenges the system’s attempts to erase their humanity.

The book thus reframes witchcraft not as something supernatural, but as a form of resistance that turns the girls’ pain into power.

The Grief of Motherhood and the Struggle for Agency in Reproductive Choices

A profound theme in the novel is the exploration of grief and loss, particularly regarding the girls’ experiences of motherhood within the confines of Wellwood House. The narrative underscores the trauma of being separated from their children immediately after childbirth, a loss that is felt deeply by each of the characters.

For the girls, their pregnancies are not celebrated but are framed within a context of shame and sacrifice. The emotional weight of giving birth and then having the child taken away—often without a chance for contact—serves as a brutal commentary on the control over women’s reproductive rights and the erasure of their agency.

The girls, especially Fern, grapple with this devastating loss while still forming deep emotional connections with one another. The theme of grief is intricately tied to the loss of bodily autonomy, as the girls are not only denied the opportunity to raise their children but also stripped of any say in their reproductive choices.

This loss is not merely physical but emotional, as they are forced to relinquish their identity as mothers in a system designed to control and exploit them.

The Power of Sisterhood and Solidarity in Overcoming Oppression

The relationships between the girls at Wellwood House evolve throughout the story, highlighting the transformative power of sisterhood. Initially, the girls’ interactions are defined by suspicion, rivalry, and isolation, but as they endure the same emotional and physical trauma, their bonds grow stronger.

This sisterhood becomes a sanctuary for the girls, a space where they can share their pain, fears, and resistance strategies in secrecy. The solidarity that emerges from their shared experiences of oppression enables them to challenge the institutional control that seeks to tear them apart.

Through their interactions and the creation of their own rituals, they offer each other comfort and strength, forming an unbreakable network of mutual support. The theme of sisterhood is vital not only as a form of emotional survival but also as a method of resistance against the system that tries to silence them.

It becomes clear that together, the girls are able to find meaning, hope, and even power in their shared experiences.

Historical Trauma and the Cyclic Nature of Abuse

Finally, the theme of historical trauma emerges as the girls uncover past records of former residents who suffered similar fates at Wellwood House. This discovery reveals a long-standing cycle of abuse and oppression that has persisted for generations.

The journals and keepsakes left behind by these previous residents serve as both a testament to their suffering and a warning about the repetitive nature of the system. The cyclical nature of trauma is further explored as the girls recognize how the institution exploits and erases the identities of the girls who come before them.

The trauma they experience is not unique to them but is part of a broader, deeply entrenched system of control that transcends time. By unearthing these hidden histories, the girls gain a sense of continuity, understanding that they are not alone in their suffering, but also that there is power in breaking the cycle.