The Wayfinder Summary, Characters and Themes

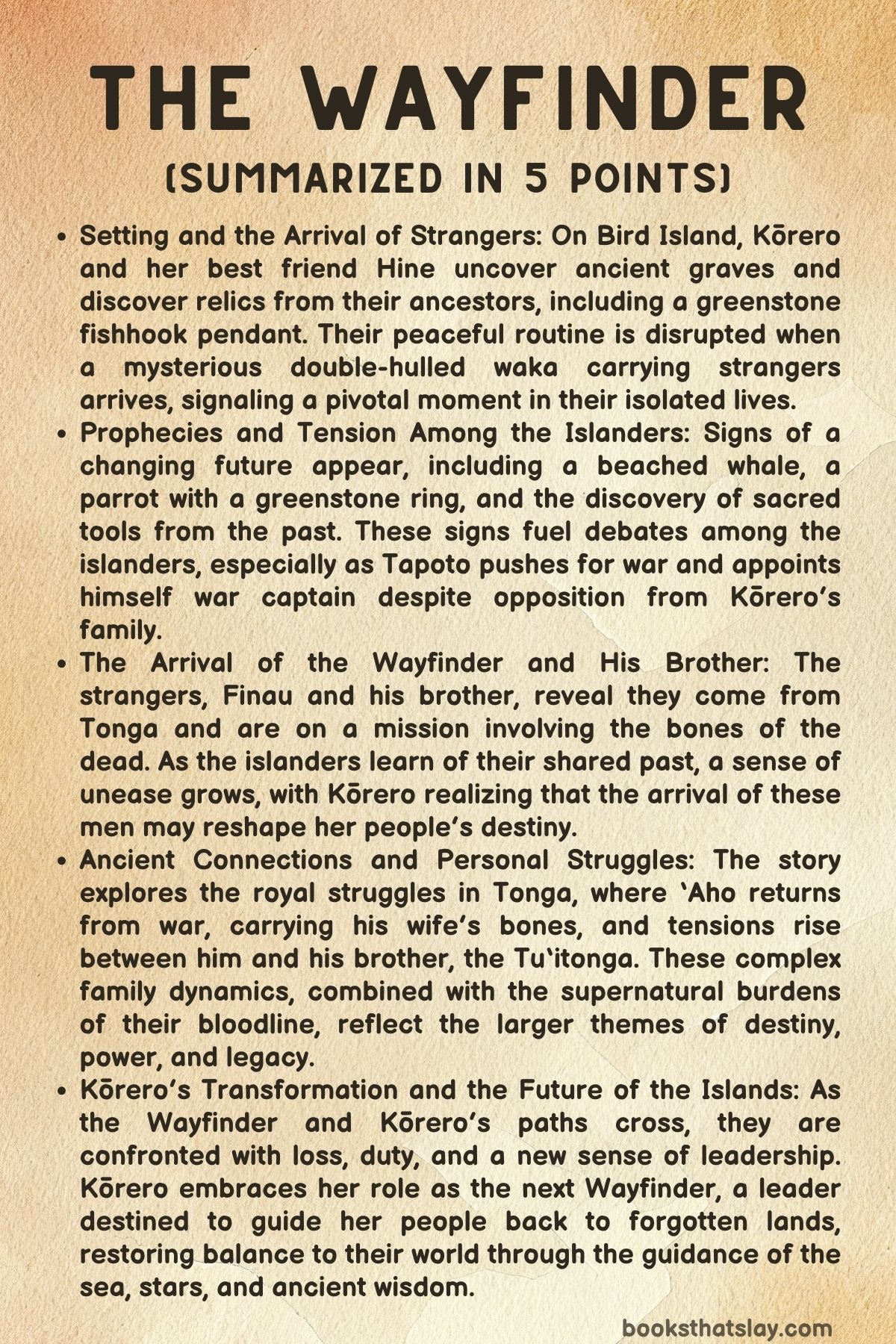

The Wayfinder by Adam Johnson is a work of speculative and historical fiction that bridges the distant future and the mythic past of the Pacific Islands. Set across isolated archipelagos and ancient kingdoms, the novel explores memory, ancestry, and survival through the journeys of navigators, storytellers, and rulers.

Blending elements of science fiction and Polynesian cosmology, it follows Kōrero, a young girl on a dying island, and Finau, a navigator descended from Tongan royalty, as their lives intersect through relics, voyages, and buried histories. Johnson’s narrative examines how knowledge and power move through generations—by story, by song, and by the enduring will to find one’s way home.

Summary

In a distant future, generations after humanity fled the mainlands, the people of Bird Island cling to survival. Kōrero, a spirited girl descended from refugees of Aotearoa, scavenges the graves of her ancestors for relics of the old world.

Among bones and ancient offerings, she uncovers a greenstone fishhook pendant—once a symbol of safe passage. Her island, once lush and alive with birds, is now a desolate place where even the skies seem to mourn.

Kōrero lives with her blind guardian Tiri, the tribe’s storyteller, and her quiet friend Hine, both of whom help her understand their fading world.

The peace of the island shatters when a massive, double-hulled canoe drifts into their cove. Its hull is marked by a frigate bird, its sails blood-red.

From it emerge two strangers, sun-darkened and tattooed, carrying sacks of bones and a parrot that recites ancient poetry. The brothers—Finau and the Wayfinder—claim descent from a faraway kingdom, Tonga, and their presence upends everything Kōrero’s people believed.

The arrival confirms the stories of other surviving lands, but it also stirs old fears of war and conquest. Tapoto, an ambitious man seeking power, declares their coming a prophecy fulfilled and demands control of the island’s defenses.

Divided between preparing for war or peace, the islanders sense the past rising from its grave.

As the newcomers integrate, Finau’s parrot mocks and sings, echoing verses of the ancestors. Kōrero, drawn to the Wayfinder’s quiet wisdom, feels both kinship and dread.

The relics she unearthed mirror those the strangers carry, suggesting a shared origin that reaches across centuries. The discovery of a sacred turtle that unearths human bones and a greenstone adze deepens the mystery—their ancestors, it seems, buried not only the dead but also the tools for their descendants’ salvation.

Far away, in the ancient kingdom of Tonga, another story unfolds centuries earlier. ‘Aho, a battle-hardened prince and brother to the Tu‘itonga (the sacred king), returns home from years of brutal war.

Haunted by loss, he carries the bones of his wife, intending to bury her among royal tombs despite taboos forbidding it. His brother, wary of his violent temper, welcomes him with ceremony but distrust.

Their reunion exposes the fissures of divine kingship—duty against blood, tradition against conscience. The Tu‘itonga seeks counsel from the souls of the dead he keeps preserved in coconuts, while ‘Aho’s rage and guilt simmer toward inevitable rebellion.

Alongside them is Māhina-e‘a, or Moon Appearing, a young woman chosen to dance in the royal court. Though clumsy, she possesses a luminous spirit that captures the prince’s son Lolohea’s attention.

Their brief connection, born of grace and melancholy, plants the seed for generations to come. The king’s tattooist, an old Samoan artist, inks sacred designs onto the bodies of warriors and princes, his craft symbolizing continuity and control.

Through tattoos, songs, and royal decrees, Tonga’s destiny is etched into flesh and myth.

In these parallel worlds—Kōrero’s future and Tonga’s royal past—the legacies of faith, violence, and migration intertwine. The Wayfinder and Finau, descendants of ‘Aho’s line, carry the physical and spiritual remnants of their world’s collapse.

Through their arrival, Kōrero’s island learns that their isolation was an illusion; history, like the sea, always returns.

Back in Tonga’s court, power begins to unravel. The Tu‘itonga dreams of comets and omens, while famine and rebellion rise.

‘Aho, consumed by guilt over his wife’s death, challenges the king to a duel of honor. His savagery overwhelms reason, and though he wins, his victory marks the beginning of his fall.

The king, mortally wounded, leaves his son Lolohea the burden of a broken realm. Lolohea ascends as the new Tu‘itonga, but his rule rejects bloodshed.

He frees captives, ends the wars, and tries to unshackle Tonga from centuries of divine hierarchy. Yet peace proves as dangerous as war, and tradition demands its price.

Meanwhile, Finau and the Wayfinder travel across decaying islands, carrying the bones of their ancestors and the weight of their lineage. They meet Kōrero and her people, whose legends speak of the same gods and canoes that once launched from Tonga.

As they explore a nearby volcanic island, they encounter Ihi, a girl left alone after war destroyed her village. She leads them through ruins filled with relics—the Red Cloak, sacred spears, and the symbols of the ancient navigators.

There, the brothers confront their mission: to deliver “life” by restoring the fractured balance between the living and the dead. But what they truly seek is redemption—for their family, their empire, and themselves.

As hunger and fatigue press on, Ihi reveals that her people once warred over sacred laws and divine favor, forgetting they all came from the same ancestral canoe. Her story echoes Kōrero’s own history, binding the two threads of the novel.

Together, they decide to leave the cursed island, guiding Ihi toward safety. The Wayfinder teaches Kōrero to read the stars, passing on the art of celestial navigation.

Under a new moon, their canoes glide over silent waters, steering by instinct and faith.

Back in Tonga’s timeline, chaos reigns after the Tu‘itonga’s death. Lolohea’s reforms ignite revolt, and the Tamahā—the royal aunt and highest authority—struggles to maintain order.

The brothers Finau and the Wayfinder flee the collapsing kingdom, carrying relics and memories of their father’s sins. When they reach Bird Island generations later, they bring with them not conquest but a final chance at renewal.

In the novel’s climactic scenes, Tapoto, now a self-declared war leader, faces ‘Aho—the embodiment of tyranny reborn. A duel ensues beside a sacred pool, witnessed by gods and mortals alike.

Through courage and sacrifice, Kōrero and her companions overcome him, wielding the magical Fan, a relic capable of life and death. When ‘Aho falls, Kōrero chooses mercy over vengeance, cutting away the marked hand that bore his crimes rather than ending his life.

This act transforms her from gravedigger to healer, from island girl to leader.

As the storm passes, the people proclaim her the new Tamahā, guardian of sacred law and balance. The Wayfinder, now king, crowns her with the greenstone fishhook—a symbol of guidance and journey.

Together, they represent the convergence of past and future, myth and survival. The Fan, once a weapon of destruction, becomes an emblem of restoration.

In legend, Kōrero endures as the Wayfinder who navigated between forgotten worlds, reviving dead lands and teaching lost generations to listen to sea and star alike. The tale closes where it began: on Bird Island, with voices carried by the wind and the promise that even in ruin, the way forward can still be found.

Characters

Kōrero

Kōrero is the protagonist of The Wayfinder, a young woman from an isolated island who carries the weight of her people’s history while also grappling with the changes that the arrival of outsiders brings. She is a curious and introspective character, caught between her deep connection to the past and the shifting present.

Kōrero is strong-willed and resourceful, as seen in her exploration of ancient graves and her discovery of relics that tie her to the lost world of her ancestors. She has a complex relationship with her parents, particularly her mother, who is a tattoo master, as well as with the tribe’s expectations.

Kōrero’s evolution from a girl who is uncertain about her future to someone who ultimately takes on a leadership role highlights her growth. Her interactions with the strangers, particularly the Wayfinder, reflect her inner conflict—torn between fear and fascination with the outside world.

She is destined to become a navigator, a position that symbolizes her transformation from a passive observer of history to an active force in shaping the future of her people.

Tapoto

Tapoto, the self-proclaimed war captain of the island, is one of the most ambitious and power-hungry characters in The Wayfinder. His desire for control and recognition drives much of the island’s conflict.

Despite his laziness and lack of genuine leadership qualities, he is determined to manipulate the circumstances for his own gain, such as by interpreting signs and events in ways that serve his ambitions. Tapoto’s actions often border on reckless, as seen when he defies sacred rules, like attempting to capture the sacred turtle or demanding the moko tattoos, which symbolize earned authority.

His character arc revolves around his constant need for validation and power, which ultimately leads to his downfall. Though he is defeated in a duel with ‘Aho, his eventual role in the final battle serves as a reminder of the fine line between leadership and tyranny.

Finau

Finau is a mysterious and quiet character who serves as a bridge between Kōrero’s isolated world and the larger, tumultuous world of Tonga. He is calm and introspective, holding a deep understanding of the past and the burdens it carries.

Unlike his brother, the Wayfinder, who is more outspoken and assertive, Finau tends to listen rather than speak, which makes him seem distant and enigmatic. His appearance on Kōrero’s island marks a pivotal moment in the story, and his connection with Kōrero is both spiritual and fateful.

Finau is linked to the past through the fishhook pendant he shares with Kōrero, which symbolizes their shared role as navigators. Throughout the story, Finau grapples with his grief and his responsibilities to his people, especially as the tensions between the brothers grow.

His sense of duty to the past and his family’s legacy is both a strength and a source of inner turmoil, especially as he begins to question whether the weight of tradition and honor is worth the sacrifices it demands.

Hine

Hine is Kōrero’s best friend and a key character in the exploration of their island’s history and future. She is more reserved than Kōrero, tending to act as a grounding force within their relationship.

Hine’s primary role in the story is to care for Tiri, the tribe’s blind storyteller, and to help Kōrero in the excavation of the ancient graves. Her quiet nature contrasts with Kōrero’s talkative one, but it is this balance that deepens their friendship.

Hine’s interactions with Kōrero allow for a deeper exploration of themes like memory, history, and the way the past shapes the present. Hine’s role becomes more significant as she faces the external challenges that arise with the arrival of the strangers.

Her calm demeanor and grounded perspective help anchor Kōrero, allowing her to make clearer decisions during moments of uncertainty.

‘Aho

‘Aho is a complex and tragic figure in The Wayfinder. He is the brother of the Tu‘itonga, the king of Tonga, and his return to the royal court after years of war sets in motion much of the tension in the story.

‘Aho is a man torn between the violence of his past and the remnants of his royal legacy. His relationship with his brother is strained, as ‘Aho harbors deep resentment toward the Tu‘itonga for the death of their mother and the control exerted over their family.

Despite his brutal past, which includes atrocities committed during his time as a warrior, ‘Aho is not portrayed as purely evil. His internal conflict—particularly his guilt over the death of his wife and his role in the war—adds depth to his character.

‘Aho’s character arc is marked by his eventual acceptance of responsibility for his past crimes and his attempt to find redemption, albeit through painful and violent means. His journey ultimately leads him to a confrontation with the king, where his fate is sealed, but his final moments hint at a man seeking a way to reconcile his actions with the consequences of his life.

Tu‘itonga

The Tu‘itonga, the king of Tonga, is an enigmatic and deeply reflective ruler, burdened by the weight of his lineage and the responsibilities of kingship. He is a man caught between tradition and the evolving world around him, and his leadership is marked by a sense of melancholy and foreboding.

As the ruler of Tonga, the Tu‘itonga is revered, but his interactions with his brother ‘Aho reveal the deep-seated tension within the royal family. The king’s power is symbolized through his ability to communicate with the dead and his reliance on spiritual guidance, which reflects the strong ties between the royal bloodline and supernatural forces.

His authority, however, is increasingly questioned by his own son, Lolohea, who begins to challenge the traditions that have long governed their society. The Tu‘itonga’s struggle with his past decisions and his ultimate fate underscores the central themes of destiny and the cyclical nature of history.

Lolohea

Lolohea, the Tu‘itonga’s son, represents a new generation that seeks to break free from the constraints of the past. As the heir to the throne, Lolohea is caught between the weight of his family’s expectations and his own desire for change.

He is idealistic and driven by a strong sense of justice, which leads him to challenge the rigid traditions that have defined his family’s rule. Lolohea’s relationship with his father is complex, as he admires the king but cannot reconcile with his authoritarian ways.

His ideals are put to the test as he ascends to the throne and begins to implement sweeping reforms, including the release of war captives and the end of slavery. His leadership is marked by his desire to create a more equitable society, but it also leads to tension with his advisers and the traditional power structures.

Lolohea’s character arc reflects the struggle of youth to redefine the future while still being haunted by the shadows of the past.

Māhina-e‘a

Māhina-e‘a, or Moon Appearing, is a character from Tonga whose story is intertwined with the royal family. She is a dancer chosen to journey to Tongatapu, though her lack of grace and skill make her an unlikely candidate.

Despite her shortcomings in dance, she embodies resilience and strength, forging her own path in a world that often expects women to conform to rigid roles. Her journey to the court of the king brings her into contact with the royal family, where she becomes entangled in the political and emotional turmoil of the kingdom.

Māhina-e‘a’s character represents the theme of destiny, as she is caught between personal aspirations and the duties imposed upon her by her family and the king. Her story serves as a counterpoint to the royal intrigues and challenges the traditional notions of what it means to be chosen by fate.

Themes

Leadership and Power

In The Wayfinder, the theme of leadership and power is explored through the struggles of various characters, particularly in the context of political authority and personal responsibility. The story presents different forms of leadership—each shaped by the characters’ ambitions, actions, and decisions.

Kōrero, for example, embodies a type of leadership grounded in wisdom and foresight, even though she is not initially recognized as a leader. Her strength lies in her ability to understand the balance between nature, tradition, and the future, making her a natural leader when the situation demands it.

Her eventual rise to the role of the Wayfinder symbolizes the shift from traditional forms of leadership, often marked by brute force and conflict, to a more thoughtful and inclusive leadership based on survival and unity.

The character of Tapoto represents the darker side of power—his ambition and desire for prestige often cloud his judgment. He seeks power without understanding the responsibilities that come with it.

His efforts to manipulate the islanders into accepting him as their war captain, despite the lack of wisdom and ethical grounding, demonstrate the destructive potential of unchecked ambition. Tapoto’s rise to power is a direct challenge to the established order, but his eventual downfall, at the hands of Sun Shower and Tapoto himself, underscores the theme that power born of selfishness and violence ultimately leads to its own demise.

In contrast, the Tu‘itonga’s reign reveals the complex nature of leadership within royal bloodlines. The Tu‘itonga is burdened by his family’s violent past and his own role in continuing that legacy.

His decisions, weighed down by the expectations of tradition, ultimately lead him to a moral crossroads where his leadership falters under the pressure of old values and changing times. His eventual death and the succession of his son, Lolohea, represent a pivotal shift in the power dynamics of Tonga.

Lolohea’s rise symbolizes the hope for a new kind of leadership, one that breaks away from the patterns of the past and seeks peace and justice. The transition from the Tu‘itonga’s rule to Lolohea’s idealism echoes the ongoing tension between traditional leadership and the need for reform in the face of changing circumstances.

Fate and Destiny

The theme of fate and destiny plays a significant role in the lives of the characters in The Wayfinder, particularly in the context of their personal journeys and the broader political and cultural changes on the islands. Characters like Kōrero and Lolohea are caught in the tension between the roles they are expected to play in society and the futures they wish to create for themselves.

Kōrero, in her search for meaning and identity, finds herself connected to the ancient legacy of her ancestors, but she also strives to carve her own path. Her eventual destiny as the Wayfinder signifies the fulfillment of a journey that connects the past, present, and future, showing how destiny is not something predetermined, but something that is shaped through actions, choices, and responses to the challenges one faces.

Similarly, Lolohea’s journey as the new king highlights the conflict between personal aspirations and the weight of responsibility passed down from previous generations. Despite his idealistic vision of peace and equality, Lolohea is inevitably pulled into the role expected of him as the king—an embodiment of his people’s legacy.

His struggles with the expectations of his royal family and the political realities he faces underscore the theme that destiny is a force that cannot be ignored, but must be navigated with care, wisdom, and compassion. His eventual merging with the sea, a symbolic return to the source of life and the natural order, reflects the idea that true peace and understanding lie beyond human control, in the acceptance of fate as part of a greater cycle.

In contrast, The Wayfinder also explores how individuals seek to change or escape their destinies. The character of ‘Aho, for instance, is marked by violence and bloodshed, yet his attempts to confront and undo the horrors of his past reveal a desire to rewrite his fate.

His eventual encounter with the narrator—where she offers him a chance at redemption—reveals the tension between accepting fate and striving to change it. ‘Aho’s tragic journey serves as a reminder that destiny is not easily escaped, and the consequences of one’s past actions cannot be undone so easily.

Memory and Ancestral Legacy

The theme of memory and the legacy of ancestors is woven throughout the novel, as characters are constantly confronted with the past and the stories of those who came before them. For Kōrero, the discovery of the greenstone fishhook pendant and the unearthing of ancient graves is a way to connect with her ancestors and understand her place in the world.

The artifacts they unearth are not merely relics of the past, but symbols of survival, culture, and identity. Kōrero’s relationship with these relics is both personal and collective, as she grapples with the weight of history and her responsibility to carry forward the lessons of her people.

The theme of ancestral legacy also plays a significant role in the development of the characters’ identities. For instance, the conflict between Kōrero’s family and Tapoto centers on the importance of tradition and the interpretation of the past.

Kōrero’s mother, as the tattoo master, holds the key to the knowledge of their ancestors, and her refusal to give Tapoto the sacred moko tattoos signifies her refusal to allow him to access the power that comes with these symbols of heritage. In her role as the keeper of tradition, she protects the legacy of the island’s ancestors from exploitation by those who seek power without understanding the true meaning behind the symbols.

In the case of the Tu‘itonga, his reign is marked by a deep connection to the ancestral spirits, which he consults for guidance. The king’s reliance on the preserved souls of the dead underscores the tension between honoring the past and moving forward into the future.

His eventual death and the passing of the crown to Lolohea signify not only the end of his personal reign but also the shift in the way the people of Tonga relate to their past. Lolohea’s idealism and rejection of the old ways represent a desire to break free from the burdens of ancestral expectations and create a new future for his people.

War and Violence

The pervasive theme of war and violence in The Wayfinder serves as a reflection of both personal and societal struggles, as characters navigate the destructive forces of conflict. The island’s history is steeped in violence, both in the form of warfare and internal strife.

This legacy of violence is particularly evident in the character of ‘Aho, whose life has been shaped by war and brutality. His actions—first as a warrior and later as a member of the royal family—are marked by the scars of violence, and his inability to escape his past serves as a powerful commentary on the cyclical nature of violence and its impact on individuals and societies.

The tension between peace and conflict is also explored through the actions of the islanders, who must decide whether to prepare for war or to seek peace with the incoming strangers. Tapoto’s push for war, driven by his desire for power, stands in stark contrast to the more measured and thoughtful approach of Kōrero’s family, who seek to preserve the fragile balance of their world.

The violence that follows—both in the form of physical battles and the psychological toll it takes on the characters—highlights the destructive nature of conflict and the difficult choices faced by those in power.

The theme of war and violence reaches its peak in the confrontation between ‘Aho and the forces of the Wayfinder and his allies. The brutal duel, the violence of the war dogs, and the eventual death of ‘Aho highlight the price of power and the irreversible consequences of violence.

However, the final act of mercy—where the narrator offers ‘Aho the chance for redemption by severing his hand—symbolizes the possibility of healing, even in the face of the most destructive forces. The resolution of the conflict suggests that while war and violence may define the past, it is the willingness to seek peace and forgiveness that determines the future.