Good Spirits Summary, Characters and Themes

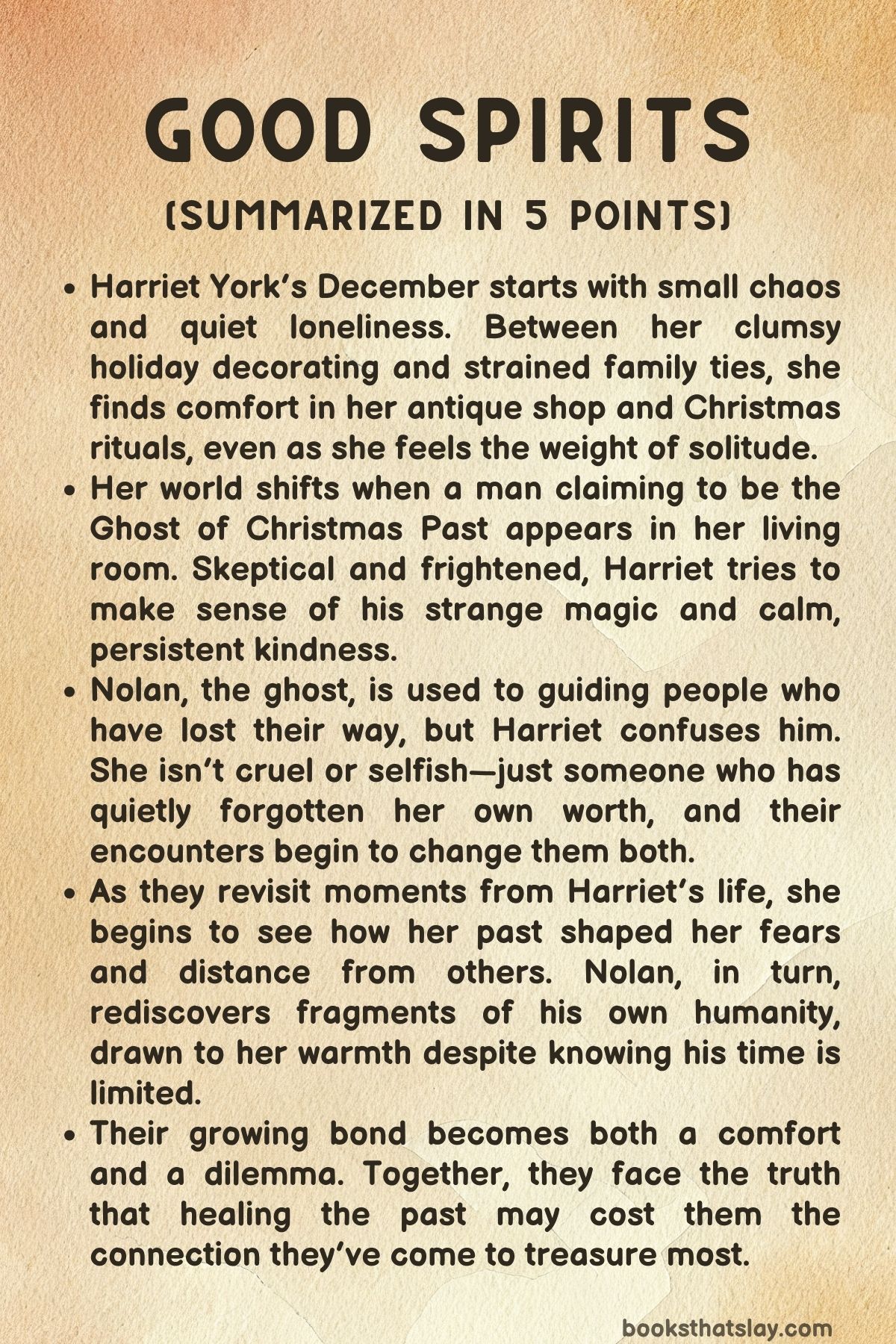

Good Spirits by B.K. Borison is a contemporary holiday romance that blends humor, warmth, and the supernatural into a tender exploration of love, memory, and redemption. Set in the charming town of Annapolis, the story follows Harriet York, an antique shop owner with a kind heart but a lonely spirit.

Her quiet December takes an unexpected turn when she is visited by Nolan, a mysterious Ghost of Christmas Past. What begins as a haunting soon turns into a heartfelt journey through time and emotion, where both Harriet and Nolan must confront their histories, rediscover hope, and learn what it means to truly live and love again.

Summary

Harriet York begins December with a series of small disasters—tripping over her cat, Oliver, injuring her knee, and facing a long day of minor frustrations. Her life in Annapolis is quiet and routine, centered around her antique store, the Crow’s Nest, a legacy from her late Aunt Matilda.

Despite her cheerful exterior, Harriet carries the ache of estrangement from her family, particularly her sister, Samantha. When her mother’s formal invitation to the annual York Family Christmas Gala arrives, it stirs old feelings of nostalgia and exclusion.

The day ends as it began—with Harriet alone, wrapped in a blanket, watching White Christmas, and clinging to small rituals that bring her comfort.

Her solitude is broken when she discovers a strange man standing in her living room. Startled, she attacks him with the TV remote, only to learn he is Nolan, the Ghost of Christmas Past.

Calm and courteous, he insists he’s been sent to help her “mend her ways.” Harriet, practical and skeptical, refuses to believe him. When he vanishes and reappears effortlessly, her disbelief begins to waver, but she still refuses to take his hand when he offers to show her her past.

Nolan leaves with a promise to return the next day, and Harriet is left questioning her sanity.

The next morning, Nolan reappears at her shop, carrying two coffees. He explains that ghosts, despite their state, often cling to human habits.

Harriet reluctantly agrees to see what he has to show her. When she finally takes his hand, the world dissolves into a storm of color, and she finds herself standing in a grand lobby from her childhood.

Watching her younger self alongside her critical mother and kind sister, Harriet is struck by memories of cold comparisons and quiet hurt. Nolan observes with curiosity, puzzled that Harriet’s past seems marked by sadness rather than cruelty or greed—the usual traits of those he’s sent to haunt.

When they return to the present, Harriet texts Samantha for the first time in years, taking a tentative step toward reconciliation.

Over the next days, Harriet and Nolan develop an odd friendship marked by humor and growing affection. His visits, once startling, become something she anticipates.

They share tea, argue playfully, and slowly begin to open up. Nolan reveals fragments of his own past: once a fisherman, he died at sea and has spent centuries serving as a spirit guide for the living.

His loneliness shows through his dry humor and old-fashioned mannerisms. Harriet, compassionate and curious, begins to see beyond his spectral role and into the man he once was.

Their next journey takes them to a Christmas tree farm from Harriet’s youth, where she watches her younger self struggle to cut down a tree alone. Nolan teases her gently, lending his mittens when her hands freeze.

The gesture turns unexpectedly tender, sparking a warmth between them neither wants to acknowledge. When they return, the air between them feels changed.

Harriet wonders if Nolan’s purpose is less about her redemption and more about his. Nolan, torn between duty and emotion, grows increasingly protective of her.

Their connection deepens through moments of quiet intimacy. When Nolan reappears after tending to his injured cat, the two share laughter and a charged closeness.

A simple touch of hands sends them tumbling into another memory, and the lines between past and present begin to blur. As they travel through her memories, and eventually his, they uncover not only Harriet’s unhealed wounds but Nolan’s forgotten humanity.

He admits that her kindness stirs something in him long dead—hope.

One night, in the soft glow of her antique shop, Nolan kisses Harriet. The kiss is electric, filled with life and longing.

Yet the joy is bittersweet when he confesses that come Christmas Eve, his magic will fade, and she will forget him. Harriet, heartbroken, vows to remember anyway.

They cling to each other, sharing a fragile happiness even as time runs out. Their next journey takes them to the early 1900s, where they meet Nolan’s human self—a lonely fisherman in a seaside cottage.

Harriet helps him piece together memories of his family, his home, and the candle his mother lit to guide him back from sea. She encourages him to remember who he was, reminding him that his story matters.

Their time together grows more intimate and emotional. Each journey leaves them weaker but more connected.

When Nolan’s magic spirals out of control, they find themselves lost between his death and her memories, their lives flashing before their eyes. They awaken in Harriet’s shop, drained but alive.

That night, they give in to their love fully, finding solace in each other’s arms. Nolan’s magic fills the room with snow and light, reflecting the impossible beauty of their bond.

But their joy is interrupted when Isabella, Nolan’s superior, appears to warn him that his attachment endangers them both. He must complete his mission before Christmas Eve or risk fading forever.

Despite the warning, Harriet and Nolan steal moments of ordinary joy—baking, joking, and sharing stories. Harriet learns that her cat, Oliver, is actually Nolan’s old pet, Builín, who’s been waiting for his master’s peace.

Their laughter gives way to quiet grief when Nolan admits he doesn’t want to move on. He hides his compass—the object tied to his unfinished business—because he’s afraid it will take him away from her.

But Harriet, selfless and brave, insists that he deserves rest, even if it means goodbye.

Their final journey takes them to the storm that claimed Nolan’s life. Harriet watches in horror as his fishing boat capsizes.

In a desperate attempt to reach him, she falls into the freezing sea. Beneath the water, she sees his body and feels her life slipping away until a hand pulls her back.

When they return to the present, drenched and gasping, Nolan realizes something profound: in his final moments centuries ago, he had seen her—her pink coat, her reaching hand. She was the light that guided him home.

Their souls had always been connected.

As Christmas arrives, they exchange gifts. Nolan gives Harriet a scarf matching his mittens; she returns his lost compass.

When he touches it, the needle points to her. She is his unfinished business—his reason to return.

But the magic that binds them cannot hold forever. He fades in her arms, promising, “I’ll see you tomorrow.”

Harriet rebuilds her life, keeping a candle in her window as Nolan’s mother once did. Weeks pass, and though the world believes she imagined him, she holds faith.

Meanwhile, in a quiet realm beyond life, Nolan meets Isabella and Matilda, who reveal that love has rewritten his fate. Given the choice between peace and returning, he chooses Harriet.

On a snowy evening, as Harriet prepares to blow out her candle, there’s a knock at the door. Nolan stands on her porch, alive and smiling.

When she asks what happens next, he answers that he will see him tomorrow and the tomorrow after that making her realize that the story is far from over.

Characters

Harriet York

Harriet York is the emotional core of Good Spirits, a woman whose life oscillates between order and quiet chaos. At first glance, she appears as a small-town antique shop owner with a fondness for Christmas rituals, peppermint tea, and the comforting familiarity of her cat and her store, the Crow’s Nest.

Beneath this outward warmth, however, lies a woman burdened by emotional isolation and the weight of unhealed wounds. Her strained relationship with her family—especially her mother and estranged sister, Samantha—reflects her lifelong struggle to meet impossible expectations while preserving her sense of self.

Harriet’s compulsive helpfulness, her avoidance of confrontation, and her almost obsessive adherence to routine all stem from a deep-seated fear of rejection. Yet, throughout the story, Harriet’s journey with Nolan forces her to face her past and the emotional scars she has long buried.

The supernatural experiences strip away her defenses, revealing a woman capable not only of forgiveness but of immense courage and empathy. Her transformation—from a woman merely surviving the holidays to one who actively reclaims her joy and agency—makes her one of B.K. Borison’s most richly layered heroines.

Nolan

Nolan, the Ghost of Christmas Past, embodies melancholy, mystery, and yearning. Once a solitary fisherman, his death bound him to a spectral afterlife where he serves as a guide for others, helping them confront the mistakes of their pasts.

His existence is one of endless detachment—until he encounters Harriet. Initially, Nolan approaches his assignment with weariness and suspicion, confused as to why someone seemingly kind and selfless like Harriet requires redemption.

But as their time together unfolds, his hardened exterior begins to soften. Nolan’s dry humor and stoic demeanor conceal a deep vulnerability and a profound loneliness that Harriet instinctively understands.

His growing affection for her reawakens his long-dormant humanity, culminating in the revelation that she is his unfinished business—his reason for lingering between life and death. Through Harriet, Nolan not only rediscovers love but also his own identity and purpose.

His final choice to return to the mortal world for her transforms him from a ghost burdened by duty into a man reborn through love and memory.

Samantha York

Samantha York, Harriet’s sister, exists at the emotional periphery for much of the story, yet her influence on Harriet’s psyche is significant. Their childhood closeness, followed by years of estrangement, underscores the novel’s themes of loss and reconnection.

Samantha represents both the familial love Harriet yearns for and the pain she tries to avoid. Their eventual reconciliation mirrors Harriet’s internal healing—by mending the bond with her sister, she symbolically restores a part of herself long broken.

Samantha’s character also serves as a quiet mirror to Harriet’s growth: where Harriet isolates herself through kindness that borders on self-effacement, Samantha copes through avoidance and silence. The tenderness of their reunion suggests that love, though fractured, can always be reclaimed.

Aunt Matilda

Aunt Matilda, though deceased, looms large in Harriet’s life as both mentor and guardian spirit. The Crow’s Nest, which Harriet inherits from her, becomes a living monument to Matilda’s memory—a space where sentiment, nostalgia, and the beauty of imperfection thrive.

Matilda’s presence continues into the afterlife, revealed when she appears alongside Isabella in the supernatural realm. She represents unconditional love, the kind Harriet never received from her mother.

Through her posthumous guidance, Matilda helps bridge the divide between the mortal and the spiritual, reminding both Harriet and Nolan that love transcends even death. Her role reinforces the story’s emotional foundation: that true connection is eternal, and the people we lose remain with us in unseen ways.

Isabella

Isabella, the stern head of the Holiday Spirits organization, is a figure of order, justice, and cosmic balance. At first, she seems a bureaucratic reaper, detached and rule-bound, ensuring that spirits like Nolan fulfill their duties.

However, as the story unfolds, Isabella reveals complexity beneath her rigidity. She embodies the tension between duty and compassion—pressuring Nolan to complete his haunting while understanding the emotional cost it exacts.

Her interactions with both Nolan and Harriet expose the paradox of her role: she must enforce the boundaries of the supernatural world even as she empathizes with those who challenge them. In the end, Isabella’s willingness to allow Nolan to choose love over eternity suggests that even in the realm of spirits, mercy and humanity prevail.

Darryl

Darryl, the forgetful yet well-meaning postman, serves as comic relief in the early chapters but also subtly anchors the story in community and human connection. His repeated blunders with mail deliveries highlight Harriet’s instinctive kindness—her readiness to help others even when inconvenienced.

Though minor, Darryl’s presence humanizes Harriet’s daily life, contrasting the magical chaos brought by Nolan with the gentle absurdities of ordinary existence.

Paula

Paula, the bakery owner, contributes to the novel’s sense of place and emotional realism. Her bakery represents comfort, tradition, and the small pleasures that make up Harriet’s world.

The morning scene where Harriet is denied her favorite Danish encapsulates the theme of disrupted expectations—a day that begins imperfectly but evolves into something extraordinary. Paula’s warmth and practicality underscore the novel’s grounding in real, tactile experiences that balance its supernatural elements.

Oliver (Builín)

Oliver, later revealed to be Builín, Nolan’s cat from his mortal life, functions as a whimsical but meaningful symbol of continuity between life and death. His silent companionship links Harriet and Nolan long before they realize their fates are intertwined.

The revelation that Oliver once belonged to Nolan transforms him from a simple pet into a metaphysical thread connecting two souls across time. His presence underscores the novel’s belief in destiny and the subtle ways love manifests through the ordinary and the mystical alike.

Themes

Loneliness and the Desire for Connection

In Good Spirits, loneliness becomes the quiet undercurrent guiding both Harriet and Nolan’s journeys. Harriet’s solitude is not dramatic but habitual — a life built on routines meant to fill the silence left by family estrangement and emotional distance.

Her morning rituals, the way she keeps her home meticulously decorated, and her dedication to her shop all mask a longing for genuine companionship. The ghostly arrival of Nolan disrupts this controlled loneliness, forcing her to confront how isolation has shaped her perception of safety and self-worth.

Nolan’s existence mirrors hers in a different realm; as a spirit, he lives in perpetual separation, unseen and untouched, yearning for a human connection that his afterlife has denied him. Their relationship becomes a bridge between worlds, both literally and emotionally.

Through their growing closeness, the novel explores how companionship need not erase loneliness but can transform it into understanding and vulnerability. When Harriet begins to open her home and heart to Nolan, her isolation no longer feels like a punishment but a choice she can finally relinquish.

Their connection emphasizes that loneliness is not simply the absence of others but the absence of being known — and that love, even when fleeting or impossible, can restore a person’s sense of belonging.

Redemption and Healing from the Past

The narrative of Good Spirits centers around the act of reckoning — not as a punitive journey but as a healing one. Harriet’s confrontation with her past is gradual and deeply human, beginning with small moments of recognition rather than grand confessions.

Her childhood memories reveal patterns of emotional neglect and comparison that shaped her fear of confrontation and her need to please others. Each journey through time with Nolan strips away a layer of defensiveness, forcing her to look at her life not through guilt but through compassion.

For Nolan, redemption takes a metaphysical form. His unfinished business is not about a single misdeed but about emotional incompletion — a heart that has never known the fullness of love or peace.

When his compass points to Harriet, the novel reframes redemption as finding meaning, not merely righting a wrong. Both characters discover that absolution is not granted by external forces but achieved through acceptance — of their mistakes, their desires, and their capacity to forgive themselves.

The story ultimately presents healing as a shared act: by helping each other confront their own histories, Harriet and Nolan redefine what it means to be redeemed.

The Power of Memory and Time

Time in Good Spirits functions as both a literal and emotional force, one that bends under the weight of memory. The time-traveling sequences serve as more than supernatural spectacle; they represent the elasticity of memory — how the past is never truly gone but continuously shaping the present.

For Harriet, revisiting her memories allows her to reinterpret them with empathy, transforming pain into understanding. Her mother’s coldness, her sister’s distance, and her own mistakes are no longer fixed events but evolving truths that she can finally process.

For Nolan, time is his prison and his salvation. Bound by eternity yet denied progress, he exists outside of the temporal flow until his connection with Harriet brings him back into the rhythm of human life.

The novel’s manipulation of time reflects the idea that love and grief transcend chronology — that some connections are timeless, persisting across lifetimes. When Nolan chooses to return to Harriet, alive and human, time itself seems to reward emotional growth, suggesting that transformation and love can rewrite even the laws of existence.

Love Beyond Mortality

At the heart of Good Spirits lies an exploration of love that defies physical boundaries. The romance between Harriet and Nolan unfolds with a tension between inevitability and impossibility — a human and a ghost drawn together despite the natural order.

Their intimacy, charged with both tenderness and sorrow, questions what it means to truly belong to someone when time, death, and memory threaten to erase everything. Harriet’s love for Nolan is an act of faith; she chooses connection knowing it will end, embracing impermanence as the price of genuine affection.

Nolan’s love, meanwhile, becomes his path to rebirth — it humanizes him, restores his emotions, and ultimately gives him back his life. The novel treats love not as a mere sentiment but as a transformative energy capable of bending fate itself.

Their story demonstrates that love’s truest expression lies not in permanence but in presence — in choosing to love fully even when tomorrow is uncertain. The ending, where Nolan returns to Harriet alive, serves as a poetic culmination of this idea: love, when honest and selfless, carries the power to resurrect not only the dead but the living parts of the soul that had been lost to grief.

Family, Forgiveness, and Belonging

Family in Good Spirits is portrayed as both the source of pain and the key to healing. Harriet’s strained relationship with her mother and sister defines her adult emotional landscape, leaving her wary of closeness and reluctant to trust.

Her journey through the past reveals how inherited patterns — criticism, silence, and avoidance — fracture the bonds between loved ones. The York Family Christmas Gala invitation symbolizes both her alienation and her lingering hope for connection.

Through Nolan’s influence, Harriet learns that forgiveness does not require reconciliation but rather understanding the limitations of others. When she reconciles with Samantha, it signifies not a return to childhood innocence but a mature acceptance of their shared wounds.

The inclusion of Aunt Matilda as a guiding spirit in the afterlife deepens this theme, showing how love endures even beyond death. Matilda’s presence, nurturing yet firm, mirrors what Harriet lacked from her mother — unconditional acceptance.

By the novel’s end, Harriet’s family extends beyond blood to include Nolan, Sasha, and the memory of those who shaped her. Her final act of keeping a candle burning becomes a quiet declaration of belonging — a reminder that family, in its truest sense, is chosen through love, not birth.