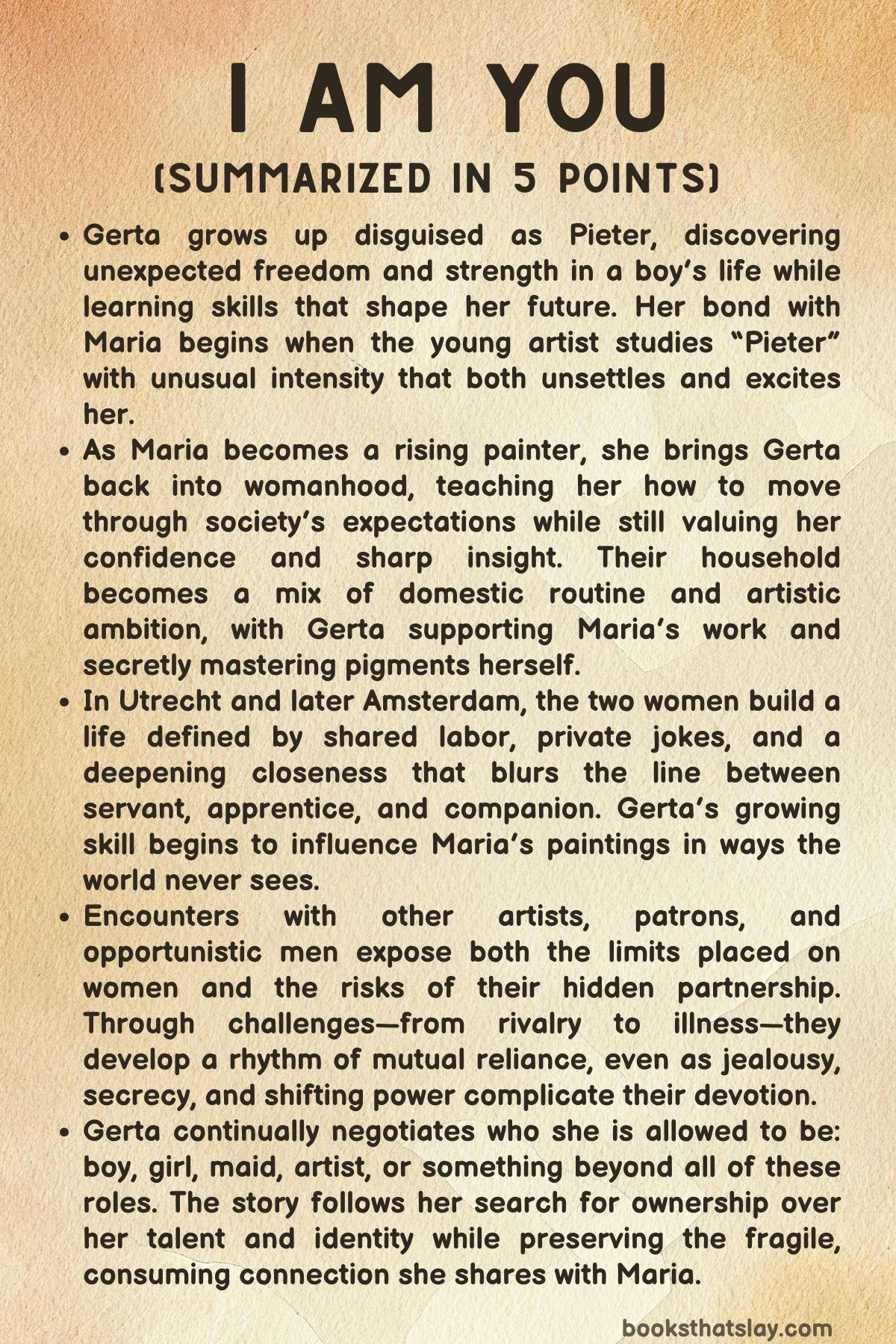

I Am You Summary, Characters and Themes

I Am You by Victoria Redel follows the life of Gerta, a girl who must live for years disguised as a boy in seventeenth-century Holland. Her transformation begins as a matter of survival but becomes a complex path into art, identity, and forbidden love.

Through her years with the still-life painter Maria van Oosterwijck, Gerta learns to inhabit several selves at once: servant, boy, girl, artist, lover, and finally an independent creator. Redel’s novel explores the shifting boundaries of gender, power, desire, and ambition, tracing how two women bind their lives and talents together while struggling against the limits of their world.

Summary

As a child in 1653, Gerta is sent away from her impoverished home to serve a minister’s household under the name Pieter Wyntges. Dressed as a boy, she discovers that life is more secure: she has steady food, a bed of her own, and far better treatment.

She learns quickly how to carry herself as Pieter, mastering the physical tasks expected of a boy and letting the memory of her earlier self fade. Living quietly, she begins observing the minister’s daughter, Maria van Oosterwijck, a young woman with extraordinary artistic talent.

Maria studies Pieter in return, sketching him during his chores and even during moments of sorrow after the deaths of his mother, father, and sisters.

Pieter learns that Maria’s ambitions exceed the narrow space allotted to women, and in an effort to please her he begins crafting inks from natural materials. Maria praises their quality and shows them to visiting painters.

Years pass, and as Pieter’s body begins moving toward womanhood, he binds his chest and maintains his disguise. One day Maria reveals that she has understood the truth for some time, and she announces her intention to bring Gerta with her when she moves to Utrecht.

With the minister’s approval, Pieter—trembling—agrees, and Maria begins retraining her to live once more as a girl. Gerta struggles with restrictive clothing and the expectations placed upon women, but she also learns the subtle social language shared among them.

She keeps her old confidence close when needed.

In Utrecht, Maria apprentices with Jan Davidsz. de Heem.

Because she cannot lodge with the male apprentices, she rents a home with Gerta. The house becomes a vivid space filled with shells, fabrics, fruits, and curiosities that fuel Maria’s inspiration.

Gerta manages the household and perfects the craft of preparing pigments. Her skill with minerals and materials grows, especially with lapis lazuli, which Maria relies upon.

At times Gerta dresses as a boy to fight her way through noisy markets to secure the finest supplies.

The two women live in close quarters, sharing daily routines, secrets, and a growing intimacy. Gerta tends to Maria’s body, dresses her hair and clothes, and becomes deeply familiar with her moods and habits.

Though she keeps her feelings quiet, they deepen with each year. After a plague outbreak, they relocate to Amsterdam, where Maria opens her own workshop.

Their new home is spacious and bright, and Gerta delights in having a room of her own.

Maria’s career flourishes. Gerta assists her, provides commentary, and maintains a bold presence in public to counter Maria’s shyness.

Well-known artists visit the studio, including Willem van Aelst, whom Maria avoids through an elaborate wager. One day Maria asks Gerta to pose without clothing so she can study a body she is never permitted to observe in public life.

The request unsettles both of them, but Gerta consents. As she stands completely exposed, Maria studies her with steady focus.

The moment marks an unspoken shift.

The story continues as Gerta becomes a hidden partner in Maria’s work. Gerta learns to draw and paint in secret, practicing at night.

Slowly she gains confidence and skill. She begins by preparing pigments, then moves to sketching objects, insects, flowers, and eventually entire compositions.

One morning she quietly adjusts Maria’s arrangement on a canvas. Instead of scolding her, Maria acknowledges the improvement, recognizing Gerta’s growth.

Gerta progresses from underpainting to painting full flowers, becoming a silent force behind Maria’s rising renown.

Their life together becomes a blend of domestic routine and artistic exploration. They joke, smoke pipes, and work side by side.

Gerta paints small landscape panels during a countryside trip, which Maria privately admires. Their bond strengthens until, during a visit to Jan Six’s home, Gerta sees Rembrandt’s portrait of Six and is overwhelmed by its rough, living intensity.

She later sneaks into Rembrandt’s studio dressed as a boy, leaves him a precious red pigment, and escapes before he wakes.

Maria’s patrons continue to grow in number. When Huygens discovers a landscape Gerta painted, Maria panics, insisting Gerta is merely a maid she has instructed lightly.

To protect Maria’s reputation and the life they have built, Gerta intentionally ruins a demonstration drawing, presenting herself as untalented. The lie strains their partnership, but after Maria indirectly apologizes, they return to their shared rhythm.

Soon their relationship becomes physical, filled with a fierce closeness that shapes their days for years.

Their harmony is disrupted when Maria reluctantly takes in her nephew Jacobus. His selfish behavior, manipulations, and deliberate provocations unsettle Gerta, who dislikes him but is also troubled by an unwanted attraction to him.

Maria, eager to be a devoted guardian, often sides with Jacobus, creating tension. After Jacobus returns to school, the lovers regain their old intimacy, but he continues planting suspicion in Maria’s mind.

As their life progresses, attention begins turning toward Gerta. Luyc the apothecary openly admires her, unsettling Maria.

Nevertheless, their public presence grows; Gerta becomes known in some circles as Gerta Pieters and attends salons. At Jan Six’s house, she sees two paintings hanging in honor that the world believes are Maria’s, though one is her own.

When her thoughtful remarks about a Rembrandt portrait are treated as playful entertainment rather than serious critique, she feels the sting of her concealed position.

One night at the docks in search of rare pigments, Maria insists on joining her disguised as a man. The port is dangerous and chaotic, and Maria becomes swept into a risky street performance before Gerta pulls her away.

The episode deepens the sense that their lives are changing.

Maria then insists they hire a maid. Gerta selects Diamanta, a quiet Portuguese Jewish girl whose competence allows Gerta more time to paint.

Soon Maria develops a tremor that grows steadily worse. She drops objects, struggles with her brush, and becomes frightened.

Gerta hides the decline by correcting canvases at night. Maria refuses doctors, depending entirely on Gerta.

Their household becomes a closed world marked by alternating calm and turmoil.

When Jacobus returns, now older and more volatile, the situation deteriorates. Maria adores him; Gerta despises him.

He mocks Gerta, plays tricks, and pushes boundaries. During a night of drunken recklessness, he assaults her.

Gerta injures his eye in defense and later, in a moment she does not fully understand, returns to him while he sleeps and forces herself on him. Their encounter becomes a violent knot of rage, shame, and desire.

The next morning Jacobus lies to Maria about the injury, and Gerta continues painting the double portrait Maria requested, adding small hidden insults within it. Jacobus leaves soon after.

Maria’s illness deepens. Gerta shoulders the full burden of the household, the studio, and every painting.

Her identity blurs: she is Gerta, Pieter, servant, artist, caretaker. Love, anger, devotion, and exhaustion overlap as her hand completes the works the world attributes to Maria.

After a long estrangement, Gerta eventually returns to Maria’s home to find her nearly unable to function. Though Maria resists help, she allows Gerta to resume her duties as Pieter.

Their relationship rebuilds slowly. Gerta discovers that Maria burned all her independent paintings, claiming it was better to destroy them herself than to lose them piece by piece.

Gerta is devastated yet strangely released.

Jacobus, now a minister, invites Maria to live with him, reigniting Gerta’s fear. To avoid this future, Gerta invents a plan for a grand performance in England that will win them money, safety, and recognition.

Maria embraces the idea, dressing them in elaborate costumes and rehearsing scenes.

On their voyage across the Channel, a brutal storm nearly destroys them, shaking Gerta’s sense of control. In England, they endure the chaos of court life and present the long-delayed painting to the queen, who is delighted.

Their staged performance follows. Gerta reenacts her transformation from boy to girl to painter, but when Maria speaks of her mother’s death, Gerta becomes overwhelmed by her real history and nearly exposes the truth of their shared work.

She stops herself, finishes the painting, and wins the crowd. Maria introduces her as “my creation,” proposing a contest between them.

Gerta wins again.

After their triumph, Gerta prepares to leave Maria permanently. She arranges protection for Maria, warns Jacobus never to harm her, and disappears upon their return to Amsterdam.

Years later, Gerta lives in Delft as an independent painter. Maria has died, still calling out for “Pieter” at the end.

Gerta reflects on their long, tangled life—a story of talent, longing, power, and loss—and accepts that Maria will always remain with her, shaping the artist she has become.

Characters

Gerta / Pieter

Gerta—who spends much of her childhood and adolescence living as the boy Pieter Wyntges—is the emotional and moral center of I Am You. Her character embodies fluidity: of gender, identity, desire, power, and artistic ambition.

As a child forced into a boy’s disguise for survival, she discovers that masculinity grants her a freedom and dignity she never had as a girl. This early experience forms the core of her selfhood: she learns to speak boldly, work hard, take risks, and rely on no one.

When she enters the minister’s household, her solitude is broken by her growing fascination with Maria, who becomes the first person to truly see her, first as a boy and later as the girl hidden beneath the disguise. As she grows older, her identity shifts again—between servant, assistant, apprentice, model, lover, and eventually co-artist.

Gerta’s lifelong oscillation between genders is less a disguise than a language she uses to navigate a world that refuses to accommodate her complexity.

Her devotion to Maria becomes both her greatest fulfillment and her greatest wound.

She pours her skill, labor, and love into another woman’s fame, often willingly erasing herself. The longing to be recognized—for her art, for her love, for her whole self—haunts her even at her most triumphant moments.

Gerta’s relationship with power is equally conflicted: she sometimes wields it to protect Maria, sometimes to protect herself, and at her darkest, she misuses it, especially in her fraught entanglement with Jacobus. By the end of the novel, she becomes someone forged through both tenderness and brutality, capable of immense love and also of damage.

Her final solitude in Delft reflects a hard-earned autonomy: she is at last an artist in her own right, yet forever marked by the woman who shaped her life.

Maria van Oosterwijck

Maria is brilliant, ambitious, impossible, and profoundly human. As a painter barred by her gender from the institutions and honors her male peers take for granted, she must be sharper, more disciplined, more politically aware, and more self-controlled than any man in her field.

She channels all forbidden desires—erotic, intellectual, spiritual, and artistic—into her work, which becomes an extension of her body, her hunger, and her thwarted potential. Her relationship with Gerta begins through attention: she studies Pieter’s movements, expressions, and emotions as if he were a living still-life, and in doing so, she awakens a lifelong intimacy between muse and maker.

As the years pass, Maria becomes dependent on Gerta not merely for household tasks but for artistic and emotional sustenance. She is affectionate yet demanding, generous yet controlling, delighted by Gerta’s talent yet terrified of being surpassed by her.

This duality shapes their bond: love becomes entangled with mentorship, rivalry, and ownership. When illness strikes, Maria’s fear of losing control deepens, leading her to destroy Gerta’s paintings—a devastating act rooted in desperation rather than cruelty.

Even in her decline, Maria clings to dignity and beauty, insisting on performance and spectacle. Her final years, calling out for “Pieter,” reveal the truth of her attachment: she loved the version of Gerta who protected her, completed her, and allowed her to remain the master of her world.

Jacobus

Jacobus is a figure of disruption—a catalyst who exposes the fragile fault lines in Gerta and Maria’s relationship. As a child, he is manipulative, sly, and perceptive in ways that unsettle Gerta, who senses the danger of a boy who sees too much.

When he returns as a young man, his charm and vanity mask a darker selfishness. He preys on Gerta’s vulnerability, taunts her with the threat of exposure, and ultimately assaults her.

Yet the narrative does not simplify him into a single dimension: he is also pitiable, a young man shaped by neglect, unsure of his place in the world, and hungry for affection. Gerta’s violent retaliation and the morally complicated revenge she takes while he sleeps complicate the reader’s perception of both characters.

Jacobus lacks the capacity for true intimacy or understanding, but he possesses an uncanny ability to sense the emotional tensions in the household. His presence sharpens the existing conflicts between Gerta and Maria, turning jealousy into fear, and fear into catastrophe.

Even after he leaves, he remains a specter of danger, a reminder of how precarious Gerta’s identity is. His later role as a minister, writing polite letters and offering Maria a home, exposes the hypocrisy and social reinvention possible for men—privileges forever denied to Gerta.

Diamanta

Diamanta enters the story quietly, yet her presence becomes a stabilizing force. A Portuguese Jewish girl fleeing her own histories of displacement, she brings discipline, precision, and emotional clarity to the household.

Though intimidated at first by Gerta’s intensity, she eventually becomes her trusted aide, allowing Gerta more time to paint and to tend to Maria. Diamanta represents a different kind of strength—one grounded not in transformation or rebellion, but in steadiness, loyalty, and quiet competence.

When Maria declines, Diamanta’s efficiency becomes essential, revealing how much the household rests on women’s invisible labor. While she never fully enters the intimate world shared by Gerta and Maria, she witnesses it all with a perceptive, unjudging gaze, offering the reader an implicit contrast: a woman who survives by remaining herself, not by remaking herself.

Luyc the Apothecary

Luyc is an emblem of the world outside the studio—a world of trade, science, markets, and human need. His admiration for Gerta is earnest and uncomplicated, which both embarrasses and reassures her.

He represents a path she will never take: a life of ordinary affection, safety, and domestic companionship. When Maria falls ill, Luyc becomes the only person Gerta allows herself to rely on.

His remedies, advice, and quiet presence show that care can be gentle rather than consuming. Though not a central figure in Gerta’s inner world, he becomes crucial in her final act of departure: it is he who promises to watch over Maria when Gerta no longer can.

Luyc’s steadiness softens the story’s darker edges, offering a vision of kindness that neither demands nor defines Gerta.

The Minister’s Family

The minister and his family serve as the foundation for Gerta’s early transformation. The minister provides structure, basic kindness, and the first environment where she can live without hunger or fear.

His household shows her the power of discipline and the routines of educated life, while his daughter’s artistic curiosity becomes the spark for Gerta’s future. Their world is strict, religious, and morally rigid, yet it is also the place where Gerta first learns to observe, to work with precision, and to slip between identities.

The minister’s gentle questioning—asking whether “Pieter” wishes to become Gerta again—marks the first time anyone asks what she wants, allowing her to shape her future rather than be shaped by it.

Jan Six and Rembrandt

These two figures represent the larger world of art—its systems, hierarchies, and possibilities. Jan Six offers patronage, exposure, and intellectual stimulation, but he also reinforces the social boundaries that keep Gerta in her place.

His condescending amusement at her insights mirrors the broader dismissal of women’s artistic ambitions. Rembrandt, seen only briefly and indirectly, becomes a symbol of artistic truth.

His raw, exposed brushwork shocks Gerta into recognizing a new possibility of expression—unpolished, emotional, and utterly honest. Her secret visit to his studio marks a turning point: she seeks not approval, but connection to a lineage of artists who create from instinct rather than propriety.

Together, Six and Rembrandt form a dual compass: one pointing toward prestige, the other toward authenticity.

Themes

Gender, Identity, and Self-Invention

Gerta’s life in I Am You is shaped by a shifting sense of identity that evolves according to necessity, survival, desire, and ambition. As a child forced into the disguise of Pieter, she discovers that gender presentation controls the way she is fed, spoken to, and valued.

What begins as practical protection becomes a revelation: as a boy she gains freedom of movement, physical confidence, and social authority she never had as a girl. This early transformation teaches her that identity can be built rather than inherited, and that selfhood is something she can shape if she is willing to endure the consequences.

As she moves between girlhood, boyhood, and the ambiguous space in between, her sense of self grows more layered. She becomes someone who can read codes across both worlds—performing obedience when required, using boyish boldness when advantageous, and carrying hidden strength even when constrained by corsets and skirts.

In her relationship with Maria, identity becomes an emotional as well as practical negotiation. Maria calls her “Pieter” long after she returns to life as a woman, folding the boy-self into their intimacy.

Gerta experiences gender less as a binary and more as a continuum shaped by work, desire, and circumstance. Over time, identity becomes a territory she revisits rather than a fixed state she must choose.

By the novel’s end, when she establishes herself in Delft, she carries the remnants of every version of herself: the resilient disguised child, the devoted assistant, the hidden apprentice, the lover, and finally the solitary artist who no longer needs a false name to secure her place in the world.

Power, Dependency, and the Hunger for Recognition

Power in this story rarely appears as open force; instead it seeps through relationships, obligations, and unspoken hierarchies. Gerta begins life powerless, yet once she is disguised as Pieter, she experiences how easily respect and safety are granted to those perceived as male.

This early lesson sets the stage for the far more complex power dynamic she later shares with Maria. Their bond is an intense mixture of love, collaboration, artistic partnership, and deep inequality.

Maria’s social standing shields her, while Gerta’s anonymity allows her to work in the shadows, contributing skill that the world believes belongs solely to Maria. Even in moments of tenderness, authority remains uneven: Maria can reveal or conceal the truth, take credit for Gerta’s labor, and dictate whether Gerta exists publicly as a maid, a muse, or nothing at all.

Yet dependency runs both ways. Maria cannot paint without Gerta’s pigments, precision, and eventually her entire artistic hand.

As Maria’s tremors worsen, this dependence intensifies until Gerta becomes the one who keeps her career, household, and dignity intact. Recognition—both earned and withheld—becomes the sharpest instrument of power between them.

When Gerta sees her landscapes admired without her name, the wound is more severe than any physical hardship she endured in childhood. Their bond thrives on mutual need but falters under the weight of unspoken competition and asymmetry.

In the final rupture, the only path to liberation becomes a confrontation with the very structure that bound them together: a public declaration of ability. By choosing to walk away after proving her skill, Gerta claims a form of recognition that no longer depends on Maria’s sanction.

Art, Craft, and the Price of Creation

Art in I Am You is not a lofty calling but a physical and emotional discipline marked by grinding minerals, binding pigments, and scraping canvases. Gerta learns early that mastery grows from repetition, patience, and the tactile experience of touching color before shaping vision.

Her years in Maria’s household turn the studio into a crucible where she discovers her capacity for observation and technique. The secrecy surrounding her apprenticeship heightens the stakes: each stroke she contributes must disappear into someone else’s reputation.

This hidden labor becomes a form of devotion, a gift she willingly offers until the imbalance becomes too painful to ignore. The novel presents creation as something that costs the body as much as the mind.

Maria’s tremors show how fragile artistic ability can be, how quickly a lifetime of skill can be threatened by illness. Gerta’s own relationship with painting becomes entangled with sacrifice: lost sleep, physical strain, and finally the destruction of her independent works.

That burning is both devastating and strangely clarifying, revealing how much of her identity has been bound to Maria’s gaze. Even their trip to England reinforces the novel’s interest in what art demands—risk, reinvention, and sometimes humiliation.

When Gerta performs her story onstage, painting before the queen, the act becomes both spectacle and confession, turning artistic creation into a confrontation with her past. By the end, art becomes the only space where she belongs fully to herself.

In Delft, surrounded by her own canvases, she finally practices the craft without disguise, fear, or borrowed authorship.

Love, Obsession, and the Entanglement of Lives

The relationship between Gerta and Maria cannot be reduced to a simple romance; it is a bond fed by admiration, longing, jealousy, resentment, and a fierce devotion that sometimes suffocates more than it comforts. Their love begins in the quiet intimacy of shared space—hands touching over pigments, glances exchanged across canvases, the trust of bathing, dressing, and confiding in one another.

As their physical relationship deepens, they build a world held together by private rituals and shared labor. Yet the same closeness that nourishes them becomes a source of volatility.

Maria’s need for moral righteousness, Gerta’s desire for recognition, and the constant pressure of secrecy create tensions that erupt in moments of cruelty or withdrawal. Their bond endures illnesses, betrayals, and the corrosive influence of Jacobus, whose presence heightens insecurity on both sides.

The intensity of their attachment blinds them to danger—emotional and physical—and makes separation feel impossible even when pain outweighs joy. When Gerta discovers her paintings burned, the violation cuts through years of affection, yet she remains bound to the woman who destroyed them.

The novel suggests that love can be both shelter and trap; that devotion can mask manipulation; and that the deepest relationships often gather contradictions that cannot be untangled. In the final act, when Gerta leaves Maria, the departure is not a triumph of independence over love but a grief-stricken acknowledgment that their connection has consumed everything but cannot sustain who she has become.

Maria remains with her always, not as a tormentor or beloved alone, but as the person who shaped her most formative years.

Secrecy, Performance, and the Masks People Wear

Secrecy functions as a constant engine in the story, shaping actions, relationships, and even artistic production. Gerta’s early disguise as Pieter prepares her to live a life built upon concealment—hiding her body, her skill, her longing, and her frustration.

Performance becomes second nature: boy in the fields, obedient maid in Amsterdam, silent hand behind celebrated canvases, and eventually the figure onstage in England whose rehearsed transformation astonishes an audience unaware of the darker truths driving the show. The society around her thrives on performance as well.

Maria must present herself as a virtuous woman even while battling jealousy, ambition, and desire. Patrons maintain polished facades while exploiting artists.

Jacobus manipulates kindness into authority, playing victim or aggressor depending on his needs. The studio becomes the one place where these masks slip, yet even there, deception lingers in unacknowledged authorship and misdirected praise.

The tension between truth and the persona one must adopt guides the novel from the opening scenes through the London performance that nearly exposes everything. What ultimately emerges is the understanding that survival often requires maintaining illusions, but growth demands breaking them.

Gerta spends years inhabiting versions of herself crafted for others, but when she chooses transparency—threatening Jacobus, leaving Maria, and stepping into a life under her own name—she sheds the final mask. The act is painful and costly, yet it grants her a future no longer shaped by disguise.

Trauma, Control, and the Struggle for Autonomy

Trauma in the novel is not a singular event but an accumulating weight carried from childhood into adulthood. Gerta’s early abandonment, hunger, and treatment as expendable labor leave marks that shape how she navigates intimacy and authority.

Her assault by Jacobus becomes a turning point where the past’s quiet wounds collide with new violations. The aftermath is tangled, leading her into acts she barely understands, exposing how trauma can warp judgment and ignite destructive impulses.

Control becomes one of the few ways she can protect herself—through mastering pigments, perfecting technique, organizing the household, and later orchestrating the England scheme. Yet control is fragile; storms, illness, and social constraints constantly push back.

Her relationship with Maria embodies this conflict: she craves autonomy but also yearns for the security Maria once provided. When Maria burns her artwork, it shatters the illusion that devotion can guard against betrayal.

The journey to England, intended as a reclamation of power, spirals into chaos, reminding her that control built on secrecy cannot hold against emotional truth. Only when she chooses solitude in Delft does she reclaim autonomy without illusion, grounding her life in the rhythm of work rather than the unpredictability of others.

Mortality, Transformation, and the Search for Meaning

Death shapes the story from the beginning: the loss of Gerta’s mother, sisters, and father fractures her childhood and teaches her that change often arrives through loss. Later, plague, storms, and the creeping decay of Maria’s health reinforce how vulnerable every human endeavor is.

Maria’s tremors and physical decline force both women to confront impermanence—not just of bodies, but of talent, reputation, and relationships. Transformation becomes the counterforce to this fragility.

Gerta changes roles, personas, and skills repeatedly; Maria shifts from rising prodigy to dependent invalid; their partnership adapts, breaks, reforms, and dissolves. Through each transformation, they search for meaning in work, companionship, and recognition.

The novel suggests that meaning is rarely found in prestige or permanence, but in the act of shaping a life despite uncertainty. By the end, Gerta accepts that she cannot preserve everything she loves, nor control the courses of the people who shaped her.

What remains is the ability to create—slowly, quietly, independently. That final image in Delft affirms that a life marked by upheaval can still hold purpose, and that the transformations born of hardship can lead to a self that is finally, fully one’s own.