Old God’s Time Summary, Characters and Themes

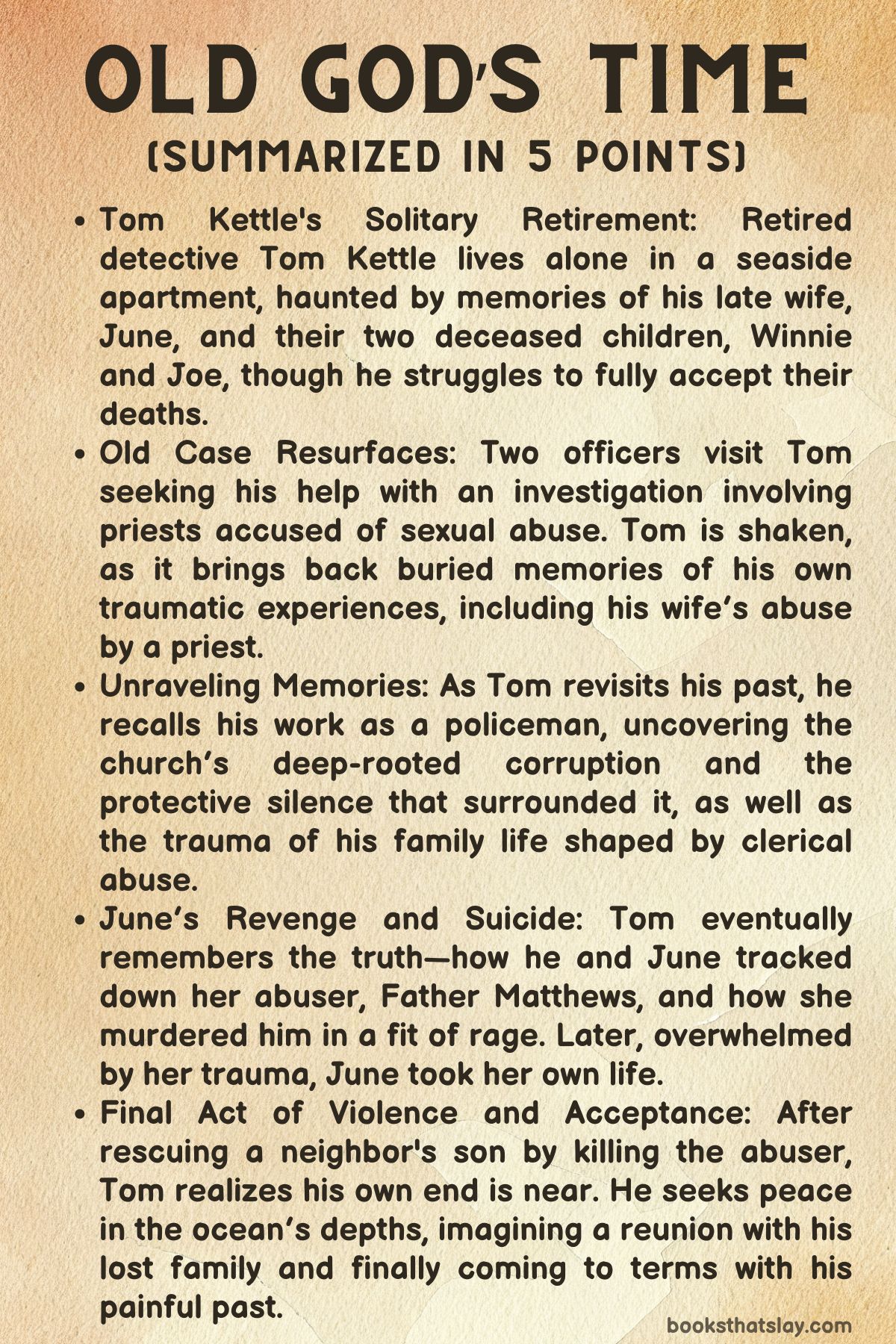

Old God’s Time by Sebastian Barry, published in 2023, is a novel about memory, trauma, and love. The story centers on Tom Kettle, a retired Irish policeman, who is confronted with the dark shadows of his past after two officers seek his help on an old case involving priests.

As the layers of Tom’s personal history slowly unravel, including painful memories of his late wife and children, he is forced to confront both the violence of his career and the unspeakable horrors of clerical abuse. Barry’s novel delves deeply into the intersection of personal grief and institutional corruption.

Summary

Tom Kettle, a retired detective, lives in quiet solitude in a rented apartment by the sea, attached to his landlord’s estate.

His days are marked by routine, with occasional visits from his neighbor, a cello player who lives an odd and detached life. Tom, in the twilight of his years, is burdened by memories of his family—his daughter Winnie, his son Joe, and his wife June, although he hasn’t fully acknowledged that all of them have passed away.

One day, two police officers from his past, Wilson and O’Casey, unexpectedly appear at his door, asking for his insights on a case involving priests. Tom feels an unsettling panic but refuses to engage, unable to confront the horrors that the case stirs within him.

Later, Tom is overwhelmed with grief, realizing he can no longer ignore the deaths of his loved ones. In a moment of despair, he contemplates suicide, but his plan is interrupted by the arrival of Fleming, his old police superintendent.

Their conversation stirs more memories of Tom’s life on the force and his early days with June, whom he met while investigating cases of abuse. Despite the haunting memories, Tom resolves to help with the case.

As he navigates his days, Tom reflects on his time in the police, recalling how officers turned a blind eye to the abuse happening within church-run institutions.

He also remembers the joy and trauma of his early relationship with June—how they met and eventually shared stories of their difficult childhoods, both shaped by abuse within the church’s care.

One day, Winnie appears to visit him, though she reminds him of the harsh reality that she now lives in the cemetery.

This revelation triggers a painful memory for Tom of his honeymoon with June, when she confessed that a priest, Father Thaddeus, had abused her as a child.

Eventually, Tom meets with Fleming, who asks about two priests Tom once investigated: Father Byrne, who had been caught photographing young boys, and Father Matthews, June’s abuser.

Though the case was suppressed by the church, Byrne is now under new accusations. Fleming reminds Tom that he had investigated Matthews’ murder, a memory Tom has long repressed.

Tom’s memories come flooding back. He recalls how June, broken by her trauma, insisted they follow Father Matthews on a mountain hike.

In a surreal moment, June transformed into a rodent-like creature and, in her rage, stabbed Matthews to death with a kitchen knife. Tom now understands that his role in this violent act will come under police scrutiny.

In the present, Tom finds himself drawn into a final act of violence. Miss McNulty’s abusive husband kidnaps her son, Jesse.

In an impulsive moment, Tom retrieves a gun from his neighbor and shoots the man. Knowing the authorities will soon arrive for him, Tom surrenders to the sea, longing for the embrace of his lost family.

As he drifts into the depths, he finds peace and wakes to the sound of his neighbor’s cello, with June sitting by his side once more.

Characters

Tom Kettle

Tom Kettle is the protagonist of Old God’s Time, a deeply complex character haunted by his past. A retired police officer, he now lives a solitary life in an apartment annexed to his landlord’s house.

His world is a fragmented mixture of reality and memories, as he struggles with grief over the loss of his wife, June, and his children, Winnie and Joe. Tom’s confusion is central to his character—his inability to fully acknowledge the death of his family reveals how deeply he is mired in emotional trauma.

He is burdened by guilt and regret, and much of the novel explores his reluctance to face the horrors of his past, particularly the abuse of power he witnessed and his participation in a corrupt system that shielded abusive priests. Tom is also a man trapped in the past, grappling with both personal and collective guilt from his time in the police force and the British Army.

The weight of these unresolved issues becomes overwhelming, leading to his eventual breakdown and suicidal thoughts. His character illustrates a man ravaged by loss and a moral reckoning that culminates in a tragic yet peaceful surrender to his fate when he allows himself to be dragged by the water, with a sense of reunion with his deceased family.

June Kettle

June, Tom’s wife, is portrayed mostly through Tom’s memories, shaping her role as an almost spectral presence throughout the novel. She was a victim of systemic abuse in her childhood, having been raped by Father Thaddeus Matthews, one of the priests investigated by Tom and his police colleagues.

This traumatic past haunts her throughout her life, and it becomes particularly harrowing when she realizes that the man Tom is investigating is her abuser. June’s breakdown and eventual suicide by self-immolation are shocking and emblematic of the deep scars left by her abuse.

While Tom remembers their life together with great affection and recalls their happiness, June is ultimately unable to overcome her trauma. Her death devastates Tom and is a central element of his unraveling. June’s character symbolizes the long-term consequences of clerical abuse and the destructive impact it has on survivors.

Winnie Kettle

Winnie, Tom and June’s daughter, is another character who appears primarily through memory. She represents both hope and tragedy.

A promising legal trainee, Winnie’s ambition and determination suggest a future free from the traumas that engulfed her parents. However, she too falls victim to addiction, a struggle Tom helps her with by sending her to rehab.

Tragically, her addiction relapse leads to her death. Winnie’s death is a profound source of guilt and sorrow for Tom, who struggles with the idea that he couldn’t save her. Her visits to Tom, in which she reveals she now lives “in the cemetery,” symbolize Tom’s inability to face the truth about her death.

Her character, like her mother’s, highlights the devastating impact of familial trauma and the difficulty of escaping cycles of pain.

Joe Kettle

Joe, Tom’s son, is a more distant figure compared to Winnie, but his character still plays a significant role in Tom’s inner turmoil. Joe becomes a doctor and moves to the United States, where he grapples with his own struggles related to sexuality and identity, shaped by his traumatic upbringing in church-run orphanages.

Joe’s life is cut short when he is murdered by the angry father of one of his patients, a tragic event that adds another layer of grief to Tom’s already burdened psyche. Joe’s character, like that of Winnie, is a reflection of the damage caused by the systemic abuse that Tom and June endured. His death serves as a reminder of Tom’s inability to protect his children from the harsh realities of life.

Wilson and O’Casey

These two police officers serve as the catalysts for the novel’s plot. When they visit Tom to ask for his help in an ongoing case involving abusive priests, they unintentionally reopen the wounds of his past.

Their presence forces Tom to confront the trauma he has spent years avoiding, particularly the investigation into Father Byrne and Father Matthews. They represent the new generation of police officers dealing with the unresolved issues of the past, contrasting Tom’s more jaded, resigned view of justice.

Wilson and O’Casey are respectful but persistent, embodying the desire for accountability in cases of clerical abuse, something that was notably absent during Tom’s time on the force.

Fleming

Fleming, Tom’s old superintendent, plays a crucial role in reminding Tom of the unresolved case involving Father Matthews. His interactions with Tom are significant because they not only bring Tom’s past back into focus but also introduce doubt about Tom’s own involvement in the murder of Father Matthews.

Fleming serves as a moral mirror for Tom, forcing him to reflect on his actions and his complicity in covering up the crimes of the priests. Fleming’s role highlights the complexity of guilt and justice in the novel, as he probes into the past while understanding the ethical failures of the police force during Tom’s career.

Father Thaddeus Matthews

Father Thaddeus Matthews, who is also Father Byrne’s associate, embodies the horrific abuse of power that runs through the novel. As June’s childhood rapist, his character represents the corrupt and unchecked authority of the Church in Ireland during the time.

Matthews’s crimes are initially swept under the rug by Church authorities and the police, symbolizing the broader societal complicity in the abuse. His murder becomes a focal point in the narrative, with Tom eventually realizing that he and June took justice into their own hands by killing him.

Matthews’s character is not given much depth as an individual but rather stands as a representation of the systemic evil that has damaged so many lives, including June’s and Tom’s.

Miss McNulty

Miss McNulty is Tom’s neighbor, and her storyline adds another layer of domestic and sexual violence to the novel. She confides in Tom about the abuse her daughter suffered at the hands of her husband, leading to her daughter’s death.

Miss McNulty’s fears for the safety of her son, Jesse, create a parallel to Tom’s own fears and guilt about his family. Her character also emphasizes the theme of institutional and legal failure, as her husband was believed over her, allowing him to escape punishment for his crimes.

In a sense, Miss McNulty mirrors June, as both women are victims of male violence and both see the authorities fail to protect them or their children.

The Cellist

Tom’s enigmatic neighbor, who plays the cello at odd hours, serves as a symbolic figure in the novel. He is a recluse, much like Tom, but the music he plays—particularly “Kol Nidrei”—introduces themes of atonement and forgiveness into the narrative.

His playing of this piece while Tom reflects on his life suggests that Tom is in search of a form of spiritual absolution for his past actions. The cellist’s gun, which Tom uses to shoot Miss McNulty’s husband, becomes an instrument of justice, marking Tom’s final act of protection.

The cellist’s musings about the ghostly girl in the garden add a surreal element to the novel, linking the themes of memory, loss, and the blurred boundaries between the living and the dead.

Themes

The Haunting Legacy of Trauma and Institutional Abuse

In Old God’s Time, Sebastian Barry masterfully delves into the long shadow of trauma, particularly that inflicted by institutional abuse. Tom Kettle, a retired police officer, has spent his life repressing harrowing memories of his childhood in a church-run orphanage, where both he and his wife June suffered horrendous sexual abuse.

The novel uncovers the deep, invisible scars left by these experiences, as Tom’s inability to face the truth of his past traps him in a state of psychological stasis. His repression manifests in his disoriented and fragmented memories, his inability to acknowledge the deaths of his family members, and his resistance to revisiting the case files involving priests.

The novel presents trauma not only as a personal burden but as a systemic issue, deeply embedded in the fabric of Irish society, where religious institutions were shielded from scrutiny for decades. Tom’s struggle reflects the devastating long-term effects of such abuse, both on the individual and societal level, where the conspiracy of silence allows pain to fester across generations.

The Intersection of Memory, Guilt, and Time as a Fractured Experience

Sebastian Barry presents time as something fluid, fractured, and unreliable in Tom’s narrative. His memories of the past are not neatly ordered but instead emerge in fragmented, surreal flashes, with past and present interweaving in ways that blur the boundaries of reality.

This distorted perception of time reflects Tom’s unresolved guilt and grief. He exists in a liminal space, where the weight of past traumas and unresolved memories anchor him to his own psychological purgatory. His disjointed recollections—like his failure to initially remember investigating Father Matthews’s murder—demonstrate how the mind warps traumatic events as a form of self-preservation.

The ghostly presence of his wife and children further complicates his sense of time; Tom speaks with his daughter Winnie, long dead, as though she were still alive, indicating his inability to fully process his losses.

This fractured experience of time also intertwines with his guilt over the abuse he witnessed and perpetuated as a soldier and as a complicit member of a police force that turned a blind eye to clerical crimes.

As he revisits these memories, time becomes a vehicle through which he must confront his guilt, a reckoning that unfolds through the novel’s non-linear structure.

The Ethical Failures of Institutions and the Collusion Between Power and Morality

One of the novel’s most striking themes is the indictment of institutions—religious, legal, and governmental—that were supposed to protect the vulnerable but instead facilitated their suffering.

Tom’s experiences as a police officer and a victim of clerical abuse draw attention to the corrupting force of institutional power.

The novel demonstrates how institutions, in their pursuit of self-preservation, often collude with one another to suppress truth and justice. The unwritten police code that prevented interference with church-run organizations symbolizes a broader moral failure in society, where the moral authority of the church was placed above individual well-being.

Tom’s own participation in this system, his reluctance to challenge it during his career, and his later horror at the reality he had been part of highlight the complex ethical dilemma faced by those within these institutions.

Barry exposes how power distorts morality, with the church and state working in tandem to protect abusers like Father Byrne and Father Matthews while dismissing or silencing their victims.

This theme is underlined by Tom’s own participation in unethical acts as a soldier, killing suspected rebels without due process, which further connects the novel’s exploration of power, violence, and moral compromise.

The Destructive Force of Repressed Trauma on Familial and Personal Identity

The novel intricately portrays how repressed trauma can erode personal identity and familial relationships. Tom’s marriage to June, though built on love, is deeply scarred by their shared histories of abuse.

The trauma they endured in childhood continues to haunt their adult lives, manifesting in June’s breakdown when she recognizes her abuser in Father Matthews and ultimately in her tragic suicide.

Their inability to fully escape the shadow of their past abuse reveals how trauma insidiously infiltrates all aspects of their lives, destroying any hope for lasting peace or stability.

The Kettle family’s story is one of gradual disintegration, as each member is overwhelmed by the forces of unresolved trauma. Winnie’s battle with addiction and eventual death, Joe’s struggles with his sexuality and violent end, and Tom’s own mental unraveling demonstrate the destructive ripple effects of unacknowledged and unprocessed pain.

Through Tom, Barry explores how trauma warps personal identity, fragmenting the self and alienating individuals from their own emotions, memories, and even their families.

Redemption, Atonement, and the Weight of Moral Reckoning

At the heart of Old God’s Time lies a meditation on redemption and the possibility of atonement for past sins. Tom’s journey is one of moral reckoning, as he is forced to confront not only the abuse he suffered but also the abuses he was complicit in as a police officer and soldier.

The novel asks whether true redemption is possible in the face of such overwhelming guilt and horror. Tom’s act of shooting Miss McNulty’s abusive husband, while framed as a final, desperate attempt to protect an innocent, also signals his desire for moral closure, even if it results in his own punishment.

The repeated motif of “Kol Nidrei,” a prayer recited on Yom Kippur that seeks release from unfulfilled vows and a return to purity, serves as a thematic counterpoint to Tom’s struggle with his conscience.

In his final act of swimming into the sea, Tom seems to seek both literal and figurative absolution, surrendering himself to the forces of nature as a form of atonement.

Yet the novel leaves the question of redemption unresolved, with Tom waking in his bed, the music of atonement still playing, but with no clear resolution. Barry presents redemption not as a clean, achievable end but as an ongoing, fraught struggle with the self.