The Great Divide Summary, Characters and Themes

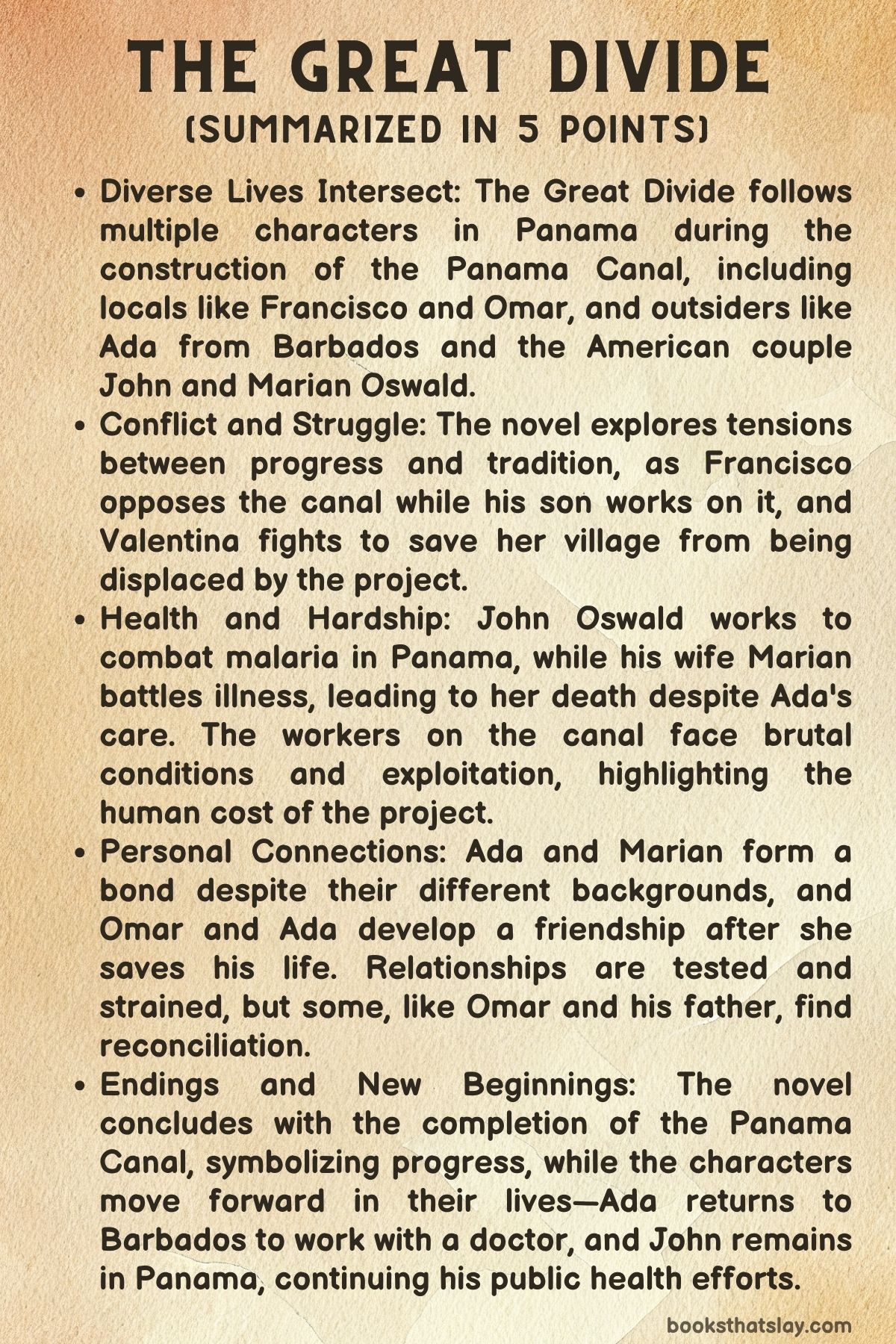

The Great Divide (2024), by Cristina Henríquez is a historical novel that brings together the lives of diverse characters during the construction of the Panama Canal in the early 20th century.

The story is told through alternating perspectives, offering a rich tapestry of experiences from locals and outsiders alike. The novel explores themes of ambition, resilience, cultural clashes, and the human cost of monumental progress, all set against the backdrop of one of the most significant engineering feats in history.

Summary

Set during the construction of the Panama Canal, The Great Divide intertwines the lives of several characters, both local Panamanians and foreigners, each grappling with the impact of this massive project.

Francisco Aquino, a Panamanian fisherman, is deeply opposed to the canal’s construction, especially since his son, Omar, has taken a job working on it, causing tension between father and son.

Ada Bunting, a young woman from Barbados, leaves her home in search of work and ends up in Panama, where she becomes entwined with the lives of John and Marian Oswald, an American couple who have moved to Panama for John’s job with the local health board, tasked with fighting malaria.

John and Marian have been in Panama for nearly a year when the novel begins. John is dedicated to his work in public health, but his social awkwardness and obsession with eradicating malaria strain his marriage.

Marian, a scientist in her own right, feels stifled in her domestic role and isolated in a foreign land. Her health deteriorates, and when she falls seriously ill, Ada is hired as her nurse. Despite the challenges, a bond forms between Ada and Marian, based on mutual respect and shared determination.

Meanwhile, Omar struggles with the harsh conditions and prejudice he faces on the construction site. His relationship with his father, Francisco, remains tense, as Francisco cannot reconcile his son’s involvement in a project he believes is destroying their homeland.

Omar’s experience is further marred by the cruelty of his foreman, Miller, and the death of a fellow worker due to the grueling conditions.

In another part of Panama, Joaquín and his wife Valentina, local residents, are fighting to save their village of Gatún, which is slated for relocation to make way for the canal. Valentina refuses to accept the government’s orders and stays behind to rally the community in resistance, despite the overwhelming odds against them.

Back in Barbados, Ada’s mother, Lucille, is struggling to raise money for a life-saving surgery for her other daughter, Millicent. Lucille eventually seeks help from Henry, the girls’ estranged father, who, despite his wife’s objections, sends a doctor to assist Millicent.

Ada remains unaware of these developments as she navigates her difficult position in the Oswald household, where she faces hostility from the cook, Antoinette.

As Marian’s condition worsens, Ada’s efforts to save her prove futile, leading to Marian’s death.

Ada is unfairly blamed by those around her, but she tries to move forward. At Marian’s funeral, she reconnects with Omar, who is grateful for the life she saved. They share a bittersweet farewell as Ada prepares to return to Barbados.

The climax of the novel centers on the protest staged by the villagers of Gatún. Though ultimately unsuccessful in stopping the relocation, the protest unites the community and imbues them with a sense of pride.

Omar, witnessing the event, begins to see the canal in a new light, recognizing its complexities. This realization helps him reconcile with his father, and they rebuild their strained relationship.

As the novel concludes, life moves forward for the characters.

Ada returns to Barbados and finds fulfillment working with the doctor who saved her sister, while John Oswald, though still battling malaria, watches the first ship pass through the completed canal, marking the end of one chapter and the beginning of another.

Characters

Francisco Aquino

Francisco Aquino is a local Panamanian fisherman who stands in opposition to the construction of the Panama Canal. He is deeply connected to his homeland and the traditional ways of life that he feels are threatened by the project.

Francisco’s resistance to the canal reflects his broader struggle against the forces of change and modernization that are sweeping through Panama. His relationship with his son Omar becomes strained because of Omar’s decision to work on the canal, which Francisco sees as a betrayal of their values and heritage.

This tension between father and son encapsulates the generational and ideological divides that the canal project exacerbates in Panama. Despite his strong beliefs, Francisco’s isolation grows as he loses connection with his son and community.

Ultimately, the narrative shows his capacity for reconciliation and understanding, as he and Omar mend their relationship by the novel’s end.

Omar Aquino

Omar Aquino, Francisco’s son, is a young man who embodies the aspirations and struggles of the working class during the Panama Canal construction. Unlike his father, Omar sees opportunity in the canal project, seeking employment and camaraderie among the laborers.

However, his experience on the job site is harsh, marred by exploitation, racism, and the brutal realities of labor conditions under the oppressive foreman Miller. Omar’s journey is one of disillusionment; he witnesses the death of a coworker, which starkly brings home the cost of the canal in human terms.

His growing understanding of the broader implications of the canal project, especially after witnessing the protest in Gatún, leads to a softening of his stance toward his father. By the end of the novel, Omar begins to seek a new path, enrolling in a preparatory course for teachers, symbolizing his desire for a better future and a move toward reconciliation and personal growth.

Ada Bunting

Ada Bunting is a teenage girl from Barbados who travels to Panama in search of work, driven by the need to support her family back home. Her journey to Panama is marked by resilience and determination, as she navigates a foreign and often hostile environment.

Ada’s experience in the Oswald household is challenging; she faces mistreatment from the cook, Antoinette, and is burdened with the responsibility of caring for Marian Oswald, a task that becomes even more difficult as Marian’s condition worsens. Ada’s character is defined by her strong work ethic and intelligence, qualities that eventually lead to a bond between her and Marian.

However, despite her best efforts, Ada is blamed for Marian’s death, which highlights the precarious position of a young, black immigrant woman in a colonial setting. Despite this, Ada maintains her strength and dignity, ultimately returning to Barbados where she finds a new purpose working with the doctor who saved her sister.

Ada’s story is one of survival and self-discovery, as she carves out a place for herself in a world that often seeks to marginalize her.

Marian Oswald

Marian Oswald is an educated, intelligent woman who finds herself stifled in Panama, where she has followed her husband John, a public health official. Despite her own scientific background, Marian is relegated to a domestic role, a situation that leaves her feeling unfulfilled and frustrated.

Her marriage to John is strained, not only by the pressures of their new environment but also by the traditional gender roles that confine her. Marian’s relationship with Ada, whom she hires as a nurse, becomes one of the few bright spots in her life in Panama, as they share a mutual respect and understanding.

However, Marian’s illness and eventual death underscore the limitations imposed on her by her gender and circumstances, as well as the tragic consequences of colonial life. Marian’s character reflects the struggles of women in a patriarchal society, particularly those who are highly capable yet constrained by societal expectations.

John Oswald

John Oswald is a white American public health official who moves to Panama with his wife Marian to work on eradicating malaria. John is depicted as an intelligent but socially awkward man who is deeply committed to his work.

His dedication to public health is sincere, but his inability to connect with the people around him, including his wife, highlights his isolation. John’s character embodies the colonial mindset of the time—he is there to “help” but remains distant from the local culture and people.

His treatment of Ada, especially after Marian’s death, reveals his underlying prejudices, despite his professional intentions. By the end of the novel, John remains in Panama to continue his work, witnessing the completion of the canal.

His story concludes with a sense of persistence, as he continues his mission despite the personal losses and challenges he has faced. John’s character is a complex portrayal of the well-meaning yet flawed colonial administrator, whose personal and professional life are inextricably tied to the imperial project.

Lucille Bunting

Lucille Bunting, Ada’s mother, is a resilient woman who remains in Barbados while her daughter travels to Panama. Lucille’s primary concern is the health of her other daughter, Millicent, who requires a costly surgery.

Her struggle to raise the necessary funds without the help of Henry, her daughters’ estranged father, highlights the difficulties faced by single mothers in a colonial context. Lucille’s refusal to ask Henry for help until absolutely necessary demonstrates her pride and determination to provide for her family on her own terms.

When she finally does reach out, the situation reveals the complicated dynamics of race, class, and gender that define her relationship with Henry and his white wife. Lucille’s character is a portrait of a mother’s love and the lengths to which she will go to protect her children, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

Joaquín and Valentina

Joaquín and Valentina are a Panamanian couple whose lives are upended by the canal construction. Joaquín, a fisherman, finds his livelihood threatened as the canal project disrupts traditional markets and ways of life.

Valentina, on the other hand, becomes the face of local resistance, determined to protect her village of Gatún from being relocated. Their struggle reflects the broader displacement and cultural erasure caused by the canal project.

Valentina’s activism, though ultimately unsuccessful in preventing the relocation, unites the townspeople and instills a sense of pride and resistance. Joaquín’s support of his wife’s efforts, despite his own struggles, shows the strength of their partnership.

The couple’s story is one of resilience in the face of colonial oppression, highlighting the human cost of the Panama Canal and the resistance of those who are determined to protect their homes and way of life.

Antoinette

Antoinette, the cook in the Oswald household, represents the entrenched social hierarchies and prejudices of the time. Her mistreatment of Ada reflects the internalized racism and classism that can exist within marginalized communities.

Antoinette’s character is not deeply explored, but she serves as a foil to Ada, highlighting the different ways in which individuals navigate their positions within a colonial society. Her actions contribute to the difficulties Ada faces, and she is one of the characters who unjustly blames Ada for Marian’s death, further illustrating the complex and often cruel dynamics of colonial households.

Henry

Henry, the father of Ada and Millicent, is a white man who had a secret relationship with Lucille, their mother. His character is largely defined by his absence and the societal barriers that keep him distant from his daughters.

His relationship with Lucille and his failure to support his daughters reflect the racial and class divisions of the time. When Lucille finally reaches out to him for help, it is not Henry himself but his foreman who comes to Millicent’s aid, symbolizing the indirect and often inadequate support that colonial systems offer to those they have marginalized.

Henry’s character is a commentary on the intersections of race, power, and responsibility, and the ways in which colonial structures fail those who are most vulnerable.

Millicent Bunting

Millicent Bunting, Ada’s younger sister, is a somewhat passive character whose illness drives much of Lucille’s and Ada’s actions. She is a symbol of vulnerability and the human cost of poverty and colonialism.

Although she does not have a direct influence on the events in Panama, her condition and the efforts to save her life underscore the novel’s themes of family, sacrifice, and the impact of colonialism on individuals’ lives. Millicent’s eventual recovery, thanks to the intervention of her father’s foreman, brings a small measure of relief and hope to her family.

Her story provides a counterpoint to the struggles faced by the other characters.

Themes

The Collision of Ambition and Displacement in the Face of Monumental Progress

In The Great Divide, Cristina Henríquez explores the collision between human ambition and the displacement it inevitably causes, particularly through the lens of the Panama Canal’s construction. The canal represents a monumental achievement in engineering and a symbol of global progress, but its realization comes at the cost of displacing entire communities and disrupting the lives of individuals who have little control over the forces shaping their world.

Joaquín and Valentina’s fight against the relocation of Gatún highlights the human cost of such progress. Their struggle is not just for their home but also for the preservation of a way of life that is being obliterated in the name of progress.

The protest staged by the townspeople, though ultimately unsuccessful in stopping the canal, serves as a powerful act of resistance and a statement on the importance of community and identity in the face of overwhelming external pressures. Henríquez uses this theme to critique the often-unquestioned narrative that progress is inherently good, revealing instead that progress for some often means loss and displacement for others.

The Intersection of Colonial Power Dynamics and Personal Agency

The novel intricately weaves together the theme of colonial power dynamics with personal agency, particularly as seen in the lives of John and Marian Oswald, Ada Bunting, and the other characters from diverse backgrounds. The Oswalds, as representatives of American power in Panama, find themselves both privileged and isolated, their personal struggles underscored by their outsider status in a land they are helping to transform.

Marian’s confinement and eventual death serve as a metaphor for the stifling effects of colonial power on those who are both complicit in and victimized by it. Ada, on the other hand, embodies the resilience and agency of the colonized.

Though she faces discrimination and mistreatment, she carves out a space for herself, first by saving Omar and later by forming a bond with Marian, and ultimately by finding her own path in Barbados. Henríquez’s portrayal of these dynamics challenges the reader to consider how colonialism not only shapes societies but also deeply affects the individual lives caught within its web, forcing characters to navigate a complex interplay of power, identity, and resistance.

The Interplay of Health, Illness, and Socioeconomic Inequities

Health and illness are central motifs in The Great Divide, serving as a metaphor for the broader socioeconomic inequities that define the lives of the characters. John Oswald’s work to eradicate malaria represents a broader effort to control and civilize the “unruly” landscape of Panama, a mission steeped in the colonial mindset.

However, his inability to fully conquer the disease underscores the limitations of such endeavors, especially when they are carried out without regard for the human lives affected. Marian’s death, in particular, becomes a poignant commentary on how health and illness are inextricably linked to one’s environment and social standing.

Ada’s journey from Barbados to Panama and back again is also marked by the constant presence of illness—whether it’s the malaria she helps treat in Panama or the struggle to save her sister Millicent back home. Through these narratives, Henríquez critiques the notion that medical and technological advancements alone can solve the deep-seated issues of poverty and inequality, highlighting instead the need for a more holistic approach that addresses the root causes of these disparities.

The Complexities of Identity Formation in Transcultural Spaces

Henríquez delves into the complexities of identity formation in the transcultural spaces of Panama and Barbados, where characters are constantly negotiating their sense of self amid shifting cultural, racial, and social landscapes. Ada’s experience as a Barbadian immigrant in Panama is marked by a duality of identity—she is both an outsider and someone deeply connected to the local community through her work and friendships.

Her journey reflects the challenges of maintaining a sense of self in a foreign land where one’s identity is constantly in flux, shaped by external perceptions and internal struggles. Similarly, John and Marian Oswald’s identities as Americans in Panama are fraught with contradictions—they are both powerful and powerless, respected and resented.

Henríquez uses these characters to explore how identity is not fixed but is rather a dynamic process shaped by the intersection of different cultures, histories, and personal experiences. The novel suggests that in such transcultural spaces, identity is always in the process of becoming, never fully realized but constantly evolving.

The Moral Ambiguity of Resistance and Collaboration

The Great Divide presents a nuanced exploration of the moral ambiguities involved in resistance and collaboration, particularly in the context of imperial and colonial enterprises. Omar’s work on the Panama Canal, despite his father Francisco’s opposition, exemplifies the complex choices individuals must make when caught between economic necessity and ethical convictions.

Francisco’s resistance to the canal is principled but ultimately futile, raising questions about the efficacy and morality of such opposition when it is bound to fail. Similarly, Ada’s relationship with the Oswalds, particularly her friendship with Marian, is fraught with tension—she is both a servant and a friend, a position that complicates the traditional power dynamics of the colonial setting.

Henríquez does not provide easy answers, instead inviting readers to grapple with the difficult choices her characters must make. In this way, the novel reflects the broader moral ambiguity inherent in any resistance or collaboration with oppressive systems, suggesting that such actions are rarely purely right or wrong but are instead shaped by a complex interplay of personal, social, and historical factors.

The Enduring Impact of Transgenerational Trauma and Resilience

Finally, Henríquez explores the theme of transgenerational trauma and resilience, particularly through the experiences of Lucille, Ada, and Millicent. The novel portrays how the legacies of colonialism, racism, and economic hardship are passed down through generations, shaping the lives of the characters in profound ways.

Lucille’s decision to reach out to Henry, the father of her children, despite the pain it causes her, speaks to the ways in which trauma can compel individuals to make difficult choices in the name of survival. Ada’s determination to support her family and build a better future for herself and Millicent is a testament to the resilience that can emerge from such trauma.

Henríquez suggests that while the wounds of the past are deep, they do not have to be defining—through connection, resistance, and self-determination, the characters find ways to transcend the limitations imposed on them by their histories. The novel thus offers a powerful commentary on the enduring impact of trauma, while also celebrating the strength and resilience of those who navigate its challenges.