The Names by Florence Knapp Summary, Characters and Themes

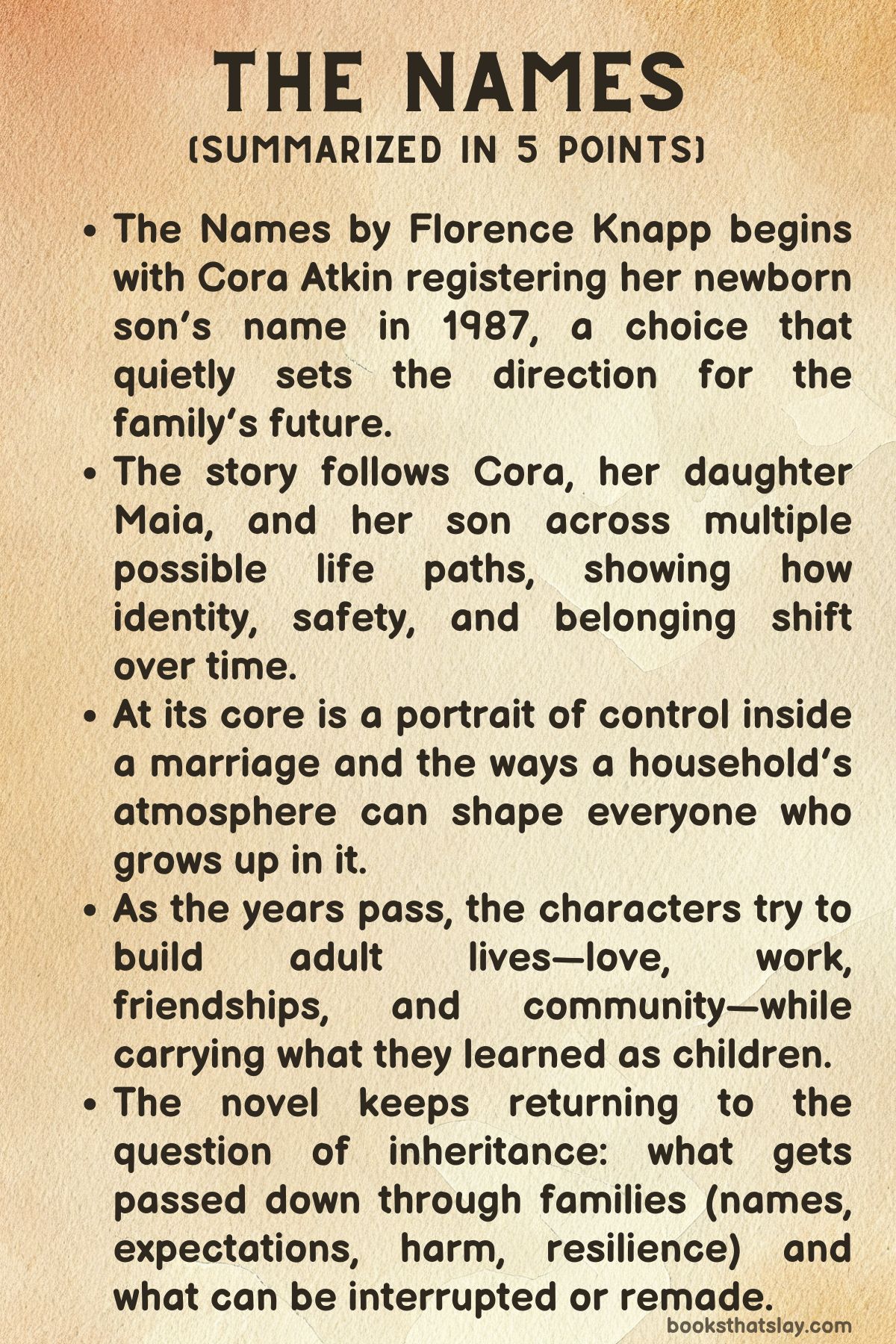

The Names by Florence Knapp is a family drama told through three possible lives that hinge on one choice: what Cora Atkin writes on her newborn son’s birth certificate during the aftermath of the Great Storm of 1987.

Cora’s husband, Gordon, demands that the baby carry the family name he insists on passing down. Cora hesitates, sensing how a name can become a script. Across the years, the story follows Cora and her children as love, fear, memory, and survival reshape them. It’s a novel about power inside a home, the afterlife of violence, and how identity can be claimed, lost, and reclaimed.

Summary

In October 1987, a violent storm tears across the United Kingdom as Cora Atkin faces a quieter crisis inside her own house. She has just given birth to a son, and her husband, Gordon, is certain the child must inherit his name, as men in his family always have. Cora despises the idea, not only because she dislikes the sound of it, but because she recognizes what it represents: a line of dominance, entitlement, and control. Walking to the registry office with her nine-year-old daughter, Maia, Cora considers other options. Maia, sensitive to the tension at home, offers names that feel like protection rather than possession. From that moment, three diverging versions of the family’s future unfold—each shaped by the name Cora chooses and by what happens when Gordon learns he has not gotten his way.

In one life, Cora registers the baby as Bear. Maia is thrilled by the softness and courage she hears in the name, and for a brief second Cora feels she has done something brave. But when Gordon sees the birth certificate, his response is immediate and brutal. He attacks Cora in their kitchen, slamming her head against the refrigerator with a violence that makes clear this is not a single outburst but an expression of who he is. Cora tries to endure in silence as she often has, yet the assault becomes so severe she screams. A neighbor, Vihaan, rushes in and pulls Gordon off her. Gordon lashes out at him too, and Vihaan is thrown through glass. Police arrive, awkward and cautious because Gordon is a doctor and a familiar figure in the community. Gordon is arrested, but the damage is done: Cora understands that even help can come with hesitation when the abuser is respected.

In the years that follow this version, Gordon goes to prison for killing Vihaan, and Cora escapes the daily terror of living with him. She moves into a flat with her children, supported by a small network that becomes her lifeline. Her mother, Sílbhe, travels from Ireland to stay with them, offering tenderness and practical care. Mehri, the mother of Maia’s friend, remains close, and her family becomes an extension of Cora’s own. Maia, though safer, carries the aftershocks: she startles easily, needs therapy, and has learned to read the world for danger. Bear grows up lively and affectionate, seeing Maia as a second parent and calling Cora “Mama Bear,” as if insisting the name can mean warmth rather than threat. Cora begins to reclaim herself in small ways—gardening work, dancing for pleasure instead of performance, and the simple relief of not calculating Gordon’s moods each hour.

In another life, Cora chooses the name Julian, believing she can satisfy Gordon’s demand for meaning while avoiding his exact legacy. The name gives Cora a strange surge of confidence, reminding her of the physical self she once trusted when she was a dancer. Yet she also knows Maia is bracing for consequences. Maia tries to manage Gordon’s temper the way children in volatile homes often do—suggesting his favorite dinner, making decorations, acting as if careful celebration might turn a dangerous man into a safe one. At the table, Cora frames the choice as a tribute. Gordon’s punishment is quieter but still humiliating: he shoves her face into the lasagna once Maia is out of the room. That night, Cora decides she cannot keep living this way, and she plans to leave.

But in this version, leaving triggers the worst outcome. When Cora finally attempts to escape, Gordon kills her. Maia and Julian are left with a grief that is also a kind of confusion, because love and fear were never neatly separated in their childhood. Gordon is imprisoned, and the children are sent to Ireland to live with Sílbhe. The grandmother’s life narrows around their needs. She suspends a romantic relationship with Cian Brennan, a jeweler, because the children’s trauma requires her full attention. Maia wets the bed nightly despite counseling and feels ashamed that Julian does not share the same symptom. Ballet becomes Maia’s way of staying close to her mother’s memory, a bodily language that keeps Cora present. Julian, still young, finds calm in repetitive making—crafting bobbin spangles for a neighbor who makes lace—work that gives him control and quiet when the world has proven uncontrollable.

Cian gradually becomes part of their recovery. Concerned about Julian’s dim sadness, Sílbhe allows Cian back into their lives, and he introduces Julian to silversmithing. The craft becomes Julian’s anchor, a way to shape beauty from metal and to prove, through skill and patience, that he is not defined by his father’s actions. Maia grows into adulthood carrying sharp memories: a brief stay in a women’s refuge with her mother, the fear of the hostel, and then the guilty relief when they returned home—a relief that later feels like betrayal. On the night Cora died, Maia covered Julian’s ears to spare him the sounds behind a locked door, but she heard everything herself. That knowledge hardens inside her as responsibility and rage.

In the third life, Cora gives the baby the name Gordon, and the decision feels like surrender. Her body reacts with disgust and exhaustion, and she begins to drift away from herself. Gordon controls even the most intimate parts of her life, forcing breastfeeding, policing food, removing small comforts, and using his medical authority as a weapon. Maia becomes an unwilling witness and a strategist, learning which words and actions might reduce danger for her mother and brother. Meanwhile, Gordon’s control extends beyond the house: he prevents contact with Sílbhe, intercepts money the grandmother sends, and builds a story that Cora is unstable. When Maia secretly mails a letter to her grandmother, Sílbhe calls and tries to help Cora flee. Cora refuses, terrified she will lose custody, and Gordon prepares for that fear by prescribing medications Cora doesn’t need—props for a future claim that she is unfit. When police check in after Sílbhe reports abuse, Cora protects Gordon with a lie, and the system lets the matter drop.

This version also follows the son named Gordon as he grows. He learns early that his father’s attention is conditional and that cruelty can be rewarded. He lies to impress his father, lashes out at school, and absorbs a warped model of masculinity. As a teenager, he assaults a girl named Lily at a party, then reshapes the story so his peers will applaud him. The act becomes a stain he carries forward, even when he later tries to change.

Across the later years in all versions, the children grow and attempt adult lives while the past keeps returning. Maia’s relationships with women are shaped by both desire and fear, and she often hides her private life, anticipating judgment. Bear, when he exists, feels pressured by the bigness of his name, chasing travel and adventure as if rest would betray who he is supposed to be. Julian, when he exists, becomes an artist who struggles with passivity and with the dread that his father’s violence lives in his blood. Cora, in the versions where she survives, wrestles with trust; even a kind man can feel like a trap because kindness once sat beside brutality in her life.

Time brings new reckonings. Gordon’s release from prison, whether as the murderous husband or the abusive patriarch, sparks dread in his family. Maia freezes when she sees him by chance, and shame floods her—not only fear, but the fear of being seen as herself. In one path, Cora discovers after her mother’s death that Gordon hid both the loss and the inheritance to keep her dependent. That discovery finally forces action. Cora reaches for help, lands at a veterinary practice where Gordon has no power, and is connected to a refuge. The escape is messy and frightening, but it holds.

The novel’s later years show that survival is not the same as peace. Bear dies suddenly during a lockdown after an allergic reaction, leaving Lily to raise their daughter, Pearl. Julian’s marriage strains under financial pressure and his stubborn refusal to sell work to England, until memory and honest conversation open a way back to his family. Maia builds a more truthful life, allowing love to be visible rather than hidden. The son named Gordon, older and sober, confronts his past, admits what he did to Lily, and fights the urge to numb himself. He also becomes, unexpectedly, a shield for his mother—using secret evidence to force his father out and to secure Cora’s home in her own name.

In the end, Gordon faces death alone, trapped with his memories. He tries to stack up the good he’s done as a doctor against the harm he caused as a husband and father, but the harm refuses to shrink. In his final moments, he imagines alternate versions of his life—moments where he walked away, where he refused his own father’s legacy, where Cora lived untouched by him, where their child carried a different name. The book closes on that uneasy truth: names matter, choices matter, and the future can pivot on one line of ink, but what people do with power matters most of all.

Characters

Cora Atkin

Cora is the moral and emotional center of The Names, not because she is idealized, but because the story keeps showing what it costs to stay human under coercive control. She begins as a woman who still has an inner voice—shaped by her past as a dancer, by the independence of leaving Ireland young, and by a clear-eyed sense that naming can be fate. That voice is repeatedly challenged by Gordon’s violence and by the social insulation his profession provides him.

Across the different life paths, Cora’s defining trait is not “strength” in the inspirational sense, but adaptability: she learns how to reduce danger, how to hide fear, how to prioritize her children’s survival minute by minute. She also carries a persistent, complicated relationship with selfhood—her body is both a site of memory (dance, appetite, motherhood) and a site Gordon tries to colonize (food, breastfeeding, medication, isolation). When she is able to leave, her recovery is not instant; it is uneven, cautious, and marked by mistrust, especially toward men who appear kind.

Her eventual capacity to accept love again signals not a simple happy ending, but a hard-earned recalibration of what safety can feel like after years of manipulation.

Gordon Atkin Sr.

Gordon is the primary engine of harm in The Names, written not as a monster from nowhere but as a man shaped by entitlement, status, and inherited cruelty. His obsession with naming is not sentimentality; it is ownership, a demand that the family orbit his identity. He uses violence as enforcement, and he uses professional legitimacy as camouflage—police discomfort around a “respectable” doctor becomes part of his protective shield.

Gordon’s control is both physical and administrative: he restricts money, communication, transport, information, and even time itself, later destabilizing Cora by confusing dates and leveraging a cognitive assessment to seize formal authority over her life.

He also weaponizes medicine, prescribing drugs to construct a narrative of Cora’s instability and to threaten custody. Importantly, the book frames his abusiveness as strategic rather than impulsive; even when he performs charm publicly, it functions as a tool to maintain social cover and isolate Cora further. His final reckoning, imagining alternate lives, does not redeem him; it instead clarifies the tragedy of choice—how often he could have stopped, and how consistently he chose dominance.

Maia Atkin

Maia is the novel’s clearest portrait of how a child becomes an expert in danger. From early on she reads adult tension, tries to manage her father’s moods, and shoulders responsibilities that belong to adults, effectively acting as a co-parent to her brother.

Her trauma is portrayed with specificity—hypervigilance, startle responses, bedwetting in one path, and a lifelong habit of scanning for consequences before expressing herself. Maia’s identity development is constrained by secrecy: she is drawn to women, but fear—of judgment, of violence, of being “seen”—pushes her into concealment and compartmentalization. This secrecy is not merely personal; it mirrors the family’s larger pattern of hiding abuse to survive, creating a painful continuity between childhood coping and adult emotional life.

Maia’s career choices also express her conflicted relationship to control and care: medicine represents competence and legitimacy, but it also sits uncomfortably beside her father’s medical authority; homeopathy, by contrast, offers a practice built around listening and relational healing, reflecting a desire to repair what was broken in how power was used in her home. Her growth arc is less about becoming fearless and more about becoming truthful—learning that silence protected her once, but limits her later.

Bear Atkin

Bear represents the imaginative alternative that naming can offer: a life not pre-scripted by patriarchal inheritance. He is characterized by warmth, playfulness, and social ease, often communicating through making—paper animals, small gestures that create connection. Yet the name also becomes a pressure system. Bear internalizes an idea that he should be bold, roaming, “bigger” than ordinary life, and this expectation shapes his adult choices, including his restlessness and distance even from people he loves.

That tension is central to his psychology: the desire to be dependable and the fear that settling down would betray the identity he thinks he must perform. His relationship with Lily exposes this conflict, as her wish for stability collides with his urge to keep moving, until crisis forces a reevaluation. Bear’s death is narratively brutal because it is not tied to moral causality; it underscores how survival from domestic violence does not guarantee safety from randomness.

In grief, he remains influential through the legacy of naming and care he leaves behind, especially in the way Lily carries their shared naming logic forward with their child.

Julian Atkin

Julian is the most introspective of the three sons, a character shaped by sensitivity and a persistent fear that he is contaminated by his father’s violence. He often experiences life as muted, emotionally flattened, and the novel uses his creative practice—silversmithing and jewelry—as both refuge and language. Making becomes a way to control what can be controlled: shaping metal, perfecting detail, creating beauty that does not harm.

Julian’s avoidance of England is not simple nationalism; it functions as a psychological border, a refusal to engage with the place connected to his mother’s death and to his father’s shadow.

He struggles with intimacy because intimacy demands risk, and risk activates his dread of becoming dangerous. His relationship with Orla highlights this: he is drawn to her, but hesitates, misreads expectations, and retreats when closeness feels like exposure. As a husband and father, Julian’s passivity becomes a secondary problem—less dramatic than Gordon’s cruelty, but still damaging, especially when it leaves Orla carrying the burden of discipline, finances, and emotional labor.

His later development depends on memory-sharing with Maia: as she recounts details of their childhood, Julian gains a clearer map of who his parents were and who he is not, allowing him to separate inheritance from destiny.

Gordon Atkin Jr.

The son named Gordon is the most unsettling study in intergenerational transmission in The Names because he embodies both victimhood and perpetration. He grows up learning that cruelty can earn attention, that women’s pain is background noise, and that masculinity is proved through domination and story control.

His sexual assault of Lily as a teenager and his later public smearing of her reveal how quickly he turns to misogynistic narratives to protect himself and secure male approval. Yet the novel does not freeze him at that moment; it follows the long, uneven process of consequence and self-recognition.

Addiction functions as both symptom and amplifier—an attempt to silence self-awareness, and a force that wrecks his life until sobriety makes memory unavoidable. His confession to an AA sponsor is not framed as absolution; it is an admission that he cannot undo what he did, only face it and refuse to repeat patterns.

Crucially, his protective actions toward Cora later—installing cameras, confronting his father, forcing him out—do not erase his earlier violence, but they do show a capacity to break with the script he was taught. He becomes a complicated figure: someone who carries guilt and tries, imperfectly, to change what he can change.

Sílbhe

Sílbhe represents steadiness, cultural rootedness, and the fierce clarity of a mother who recognizes danger even at a distance. Her relationship with Cora carries the pain of separation—Cora left Ireland young, built a life elsewhere, and then became trapped in a marriage that cut Sílbhe off.

In the timelines where Sílbhe becomes caregiver, she reshapes her entire life around Maia and Julian, sacrificing adult companionship to provide stability and emotional containment. She is not portrayed as naïve or purely nurturing; she is practical, sometimes blunt, and willing to challenge denial, including reporting abuse when she learns the truth.

Her death later, and the fact that information and inheritance are withheld from Cora, reinforces how abusers extend control by controlling knowledge. Sílbhe’s presence also anchors the theme that love can be protective without being possessive—the inverse of Gordon’s claim on family through naming and authority.

Mehri

Mehri functions as the novel’s portrait of everyday community care: observant, steady, and willing to help without demanding disclosure on her own terms. She senses what is happening in Cora’s home long before Cora can say it aloud, and she offers practical support through friendship, shared childcare, and a nonjudgmental doorway out.

In the timelines where Cora escapes, Mehri becomes chosen family, the kind of relationship that replaces what violence tries to destroy—trust, reciprocity, and the feeling of being seen without being managed. Mehri’s importance is also structural: she represents the difference a single safe adult can make, especially for Maia, who learns that adults can be reliable.

Even when physical distance or time intervenes, Mehri remains a touchstone for Cora’s ability to ask for help later, showing how small acts of solidarity can echo across years.

Fern

Fern, though not foregrounded as heavily as the central family, operates as a key childhood counterpoint for Maia: a friend whose home is safer, whose mother models attentive care, and whose presence offers Maia a glimpse of ordinary adolescence.

Fern’s role is significant precisely because it is not dramatic; she embodies normalcy, which becomes aspirational for a child raised in instability. Her connection to Maia also strengthens the idea that peer relationships can be protective when adult life is threatening, and that friendship networks often become the first place where a child tests whether honesty is survivable.

Vihaan

Vihaan appears briefly but carries enormous narrative weight as the catalyst who interrupts a lethal episode. His act—entering the home and intervening—exposes the social reality that domestic violence is often known only when someone physically steps into the private sphere.

His death, and the annual commemoration of it by Cora and her children, becomes a moral scar that refuses to fade: survival is bound up with another person’s loss. Vihaan also highlights systemic discomfort—how authorities respond differently when the perpetrator is socially powerful—making him a quiet symbol of the cost paid by bystanders who choose to act.

Felix

Felix represents a specific kind of kindness that Cora initially cannot trust: calm, professional, attentive, and noncoercive. His significance is not in grand gestures but in how he behaves when Cora is vulnerable—believing her, responding quickly, and connecting her to support without centering himself. That matters because Cora’s abuse trained her to see “nice” as a prelude to harm.

Felix’s later relationship with her, lasting across years, is written as a patient rebuilding of safety rather than a rescue fantasy. He is also narratively linked to the veterinary practice as one of the few spaces where Gordon’s status cannot reach, reinforcing the theme that escape often depends on finding institutions and people outside an abuser’s network.

Della

Della is a representative of the refuge system and a reminder that structured help can exist, even when it arrives late. Her role is practical—transport, information, contact with Maia—and she brings an outside voice that punctures the closed reality Gordon built around Cora.

Importantly, Della’s presence shifts the story from endurance to logistics: leaving is not only emotional; it is planning, transport, paperwork, and safe housing. She stands for the infrastructure of escape that survivors need, and the way one competent professional can make the difference between returning home and staying free.

Lily

Lily’s character operates on two intertwined tracks: as Bear’s partner and as the girl harmed by Gordon Jr. Her early experience of sexual assault, followed by social punishment and isolation, shows how adolescent cruelty is often enforced by groups, not just individuals.

Her later adult life—becoming a human rights lawyer representing victims—suggests not a neat transformation of pain into purpose, but a sustained commitment to protecting others from the kind of harm she endured. In her relationship with Bear, Lily also embodies the tension between independence and longing: she wants a stable partnership, yet refuses to define herself through waiting.

The Paris attack that nearly kills her adds another layer—random public violence intersecting with private histories of violation—while her survival and motherhood emphasize endurance without romanticizing suffering. Lily’s choices around naming her child reflect her attempt to create patterns that feel playful and safe, reclaiming naming as creativity rather than control.

Charlotte

Charlotte appears primarily as Maia’s partner and as a mirror for Maia’s fear of exposure. Charlotte’s steadiness contrasts with Maia’s instinct to hide, and her presence often forces Maia to confront the gap between intimacy and secrecy. When Maia recoils from Charlotte’s touch after seeing Gordon in traffic, it reveals how trauma can override present safety in an instant.

Charlotte’s role is not to “fix” Maia but to exist as a real stake in the future: someone Maia might lose if she keeps living as if danger is always imminent. She represents the ordinary courage of loving someone who is still learning how to be seen.

Kate

Kate’s function in the novel is to show how deeply Maia’s childhood conditioning shapes adult attachment. Maia keeps the relationship secret for years, not because Kate is unsafe, but because Maia still lives under her father’s imagined gaze and her family’s unspoken rules. Kate becomes the test case for whether Maia can integrate her identity rather than splitting it into private and public selves.

When Maia finally brings Kate into family space, the moment matters because it disrupts the old hierarchy where Gordon’s potential reaction dictates everyone’s behavior. Kate’s presence also underscores the theme that chosen truth can be a form of protection—naming oneself openly, instead of being named by fear.

Meg

Meg’s relationship with Maia, beginning through a client connection, highlights Maia’s shift toward a life organized by authenticity rather than avoidance. Meg is less defined through plot mechanics and more through what she makes possible: a later-in-life love that is not built on secrecy as default.

Through Meg, the novel suggests that healing is not only processing the past; it is practicing different patterns in the present, including boundaries, openness, and mutual recognition.

Cian Brennan

Cian is a counter-model of masculinity and mentorship, a maker who teaches without dominating and who listens without demanding performance. As Sílbhe’s partner and later as a mentor to Julian (and a meaningful presence for Bear in another path), he extends family through choice rather than bloodline. His craft becomes a bridge for Julian’s emotional life, offering a way to express what he cannot easily say. Cian’s gift-making—such as crafting a necklace that holds memory—turns objects into containers for grief and continuity.

He also pushes Julian toward practical courage, encouraging him to share his work beyond Ireland, challenging the protective walls Julian builds around his pain. In doing so, Cian represents a lineage not of names, but of care and skill passed on without coercion.

Orla

Orla is written as a person who refuses to accept emotional absence as a neutral trait.

She is drawn to Julian, but she is also attuned to how his fear and passivity leave her carrying the relationship. Her pregnancy and later parenthood bring logistical and emotional pressure that exposes Julian’s tendency to retreat rather than decide, and she becomes increasingly direct about what she needs: partnership, discipline with children, financial pragmatism, and present attention. Orla’s temporary departure is not framed as punishment; it is a boundary, a refusal to normalize being alone inside a marriage. Her return, when it happens, is contingent on Julian choosing active love rather than passive remorse, making her an important vehicle for the novel’s insistence that tenderness requires action.

Eileen

Eileen, the lacemaker neighbor in Ireland, is a small but resonant figure because she introduces Julian to a world where careful, repetitive craft is valued and shared. Her presence reinforces the motif of making as stability—hands producing order, pattern, and beauty in contrast to the chaos of violence.

Through Eileen’s work and Julian’s bobbin spangles, the story connects domestic artistry to emotional regulation, suggesting that tradition and craft can be forms of sanctuary.

Rob

Rob, Gordon Jr.’s AA sponsor, is the person who insists on accountability without spectacle. In scenes with Rob, the novel shifts into a moral register focused on repair and restraint: confession is not performance, and remorse is not the same as change. Rob’s steadiness provides the container in which Gordon Jr. can speak the truth about what he did and sit with the consequences. He represents a community model of responsibility, where relapse triggers and shame are addressed through choice and support rather than denial.

Comfort

Comfort enters as Gordon Jr.’s partner in later life and helps show what a healthier masculinity might look like after long damage. Her relationship with him suggests she sees both his vulnerability and his responsibility, and she participates in a family arrangement that includes Cora and Maia without collapsing into chaos.

Comfort is also linked to the possibility of stability after addiction, not as a reward, but as something built through daily reliability. She functions less as a plot driver and more as evidence that people can live differently once they stop centering the abuser’s gravity.

Ida

Ida, Comfort’s teenage daughter, calling Gordon Jr. “Gord,” subtly transforms the meaning of the name inside the family. Where “Gordon” once signaled dominance and fear, in Ida’s voice it becomes casual affection, a sign that identity can be recontextualized. Her presence also puts Gordon Jr. near a young person again, implicitly raising the stakes of his sobriety and self-control. Ida symbolizes the forward-facing part of the story: the next generation watching whether adults repeat old patterns or build new ones.

Themes

Naming, Identity, and the Stories People Are Forced to Live Inside

A name in The Names isn’t treated as a label; it functions like a first draft of a life, written before a child can object. Cora’s choice at the registry office becomes a compressed argument about who gets to define a person: a mother trying to protect, a father trying to possess, and a society that often treats family tradition as neutral even when it carries violence.

The novel keeps returning to the way identity can be assigned by others long before it is self-authored. When a boy grows up as Bear, he internalizes expectations of softness, courage, and an almost mythic warmth; when he grows up as Julian, he carries a sense of distance from England and a longing for meaning that lives in craft and memory; when he grows up as Gordon, the name becomes inheritance in its bluntest form—an enforced alignment with the father’s ego and legacy.

What’s crucial is that none of these identities are purely chosen. Each is shaped by what the surrounding adults reward, punish, or fear, and by how the world reads the name before meeting the person.

The book also shows that the “name” a character carries publicly may not be the one that governs their private self. Maia’s experience demonstrates this split most sharply: she is often treated as “the murderer’s daughter” in social imagination, even when nobody says it aloud, and she learns to pre-empt other people’s judgment by hiding parts of her life.

That pressure turns identity into management—what to reveal, what to conceal, what to perform to stay safe. Naming extends to the way trauma labels families and how shame behaves like a second surname, passed around without consent.

Yet the novel refuses a simplistic claim that a name determines destiny. Instead, it tracks how names create friction: expectations push, characters push back, and identity emerges as negotiation. By making the same family branch into different futures, The Names stresses that selfhood is never only internal; it is also an outcome of language, power, and the stories a community is prepared to believe about you.

Domestic Abuse, Coercive Control, and the Architecture of Fear

The violence in The Names is not framed as isolated “incidents” but as a system with rules, incentives, and infrastructure. Gordon’s abuse operates through obvious physical harm, but it is sustained by quieter mechanisms: monitoring, humiliation, economic restriction, manipulation of institutions, and the slow erosion of Cora’s confidence in her own perception.

The home becomes a controlled environment where ordinary objects—food, mail, radios, telephones—turn into tools of dominance. The routine of coercion matters because it explains why escape is not simply a matter of deciding to leave.

Gordon closes exits one by one: he isolates Cora from friends, blocks contact with her mother, intercepts money, hoards information, and cultivates credibility through his professional status. When he uses medical authority to imply Cora is unwell, the book exposes a particularly chilling layer: abuse that borrows legitimacy from expertise and social respectability. In that context, even the police become uncertain, deferential, relieved to accept an explanation that lets them move on.

The novel also captures the psychological shape of captivity. Cora’s dread is anticipatory; fear isn’t limited to the moment of being hit. It becomes a constant calculation of timing, tone, and risk, and that constant calculation changes a person’s inner life. The abuse affects her relationship to her own body—breastfeeding, eating, speaking, dancing—so that control reaches beneath the skin.

The story’s branching structure makes this theme even sharper because it shows how outcomes hinge on small differences while the underlying pattern of coercion remains recognizable. Whether Gordon is imprisoned early or remains in the home, the abuse leaves behind similar residues: hypervigilance, distrust, fragmented memory, and the learned instinct to protect the abuser to prevent worse consequences.

Equally important, The Names treats abuse as contagious across relationships. Maia learns to manage Gordon’s moods, becoming prematurely adult, while Cora learns to minimize conflict in ways that can look like compliance from the outside. The book doesn’t ask readers to admire endurance; it asks them to see the trap.

And it makes a pointed argument about community responsibility: neighbors, friends, and professionals may be close enough to suspect, but suspicion is not intervention. Safety arrives not through dramatic heroism, but through rare moments where someone offers concrete help without requiring Cora to prove she deserves it.

Motherhood Under Pressure and the Ethics of Protection

Cora’s motherhood in The Names is defined less by sentiment and more by decision-making under threat. She is constantly weighing imperfect options: tell the truth and risk escalation, hide the truth and risk isolation, leave and risk losing custody, stay and risk dying. The novel treats these decisions as ethical problems without clean solutions, refusing the comforting fantasy that “the right choice” will always be available if someone is brave enough.

The registry office scene becomes a concentrated version of this dilemma: naming the baby is an act of love, but it is also a safety calculation. What she writes down is both a gift to her son and a potential trigger for her husband’s violence. The book’s different paths show that even when she acts with intention, consequences can still be devastating, which undercuts simplistic judgments about what a mother “should” do.

Maia’s role complicates the theme further by showing how children are often drafted into caregiving when a parent is unsafe. Maia becomes a second mother in practice—monitoring, soothing, planning meals to prevent rage, physically comforting Cora after arguments she overhears. That is not presented as cute closeness; it is presented as a loss. Maia’s childhood is shaped around management rather than play, and the novel suggests that this kind of forced competence can persist into adulthood as a habit of self-erasure.

The impact surfaces later in Maia’s difficulty trusting intimacy and her impulse to hide her relationship, as though visibility itself invites punishment. In this way, motherhood under pressure expands into a wider portrait of care work inside trauma: who protects whom, how protection can become a burden, and how love can be expressed through secrecy because secrecy is sometimes the only available shield.

The novel also explores what happens after the immediate danger changes. When Cora survives into later years, she has to relearn the idea that her body and time belong to her. Her gardening, dancing, and tentative reconnection with companionship aren’t “recovery arcs” in the tidy sense; they are attempts to rebuild personhood in the aftermath of being reduced to a role.

The Names insists that motherhood is not only nurture; it can be strategy, endurance, compromise, and sometimes guilt—especially when a mother must measure harm and choose the smaller injury.

Trauma, Memory, and the Body as a Record

Trauma in The Names behaves less like a single wound and more like an evolving internal climate that shapes attention, sleep, desire, and identity. The novel shows memory as unreliable in a specific way: not because characters are forgetful, but because the mind hides details to keep functioning.

Cora cannot always account for the exact triggers of certain events, and that absence of clarity becomes part of the damage. Maia’s startle responses, bedwetting in one path, and later adult secrecy all point to the body carrying knowledge that the conscious mind may resist naming. Even the small recurring rituals—commemorations, avoidance behaviors, the instinct to scan faces and rooms—suggest that trauma creates routines as much as it destroys them.

The book also presents trauma as something shared but unevenly distributed. Siblings can live through the same household yet carry different burdens: Maia often remembers too much, Julian sometimes experiences the world as muted, and Bear’s personality expresses both resilience and the pressure of expectation.

The different versions of the family allow the story to highlight how trauma is influenced by timing, witnesses, and the narratives available afterward. A child who grows up with a living mother can have a different relationship to fear than one whose mother is killed, yet both can be marked by what they were forced to hear, hide, or explain.

Importantly, The Names connects trauma to artistry and craft without romanticizing suffering. Julian’s silversmithing is not portrayed as pain magically turning into beauty; it functions as a discipline that gives shape to emotions too large for ordinary speech.

Repetition, precision, and making become ways to exert control in a life where control was stolen. Maia’s attraction to healing work similarly emerges from experience: listening to others becomes a practiced skill, but it also risks turning her into someone who is always managing pain—hers and everyone else’s.

The novel’s attention to sensory triggers—the smell of a tree, the texture of a coin, the sight of a painting—underscores that memory is often stored in sensation. Healing, when it comes, arrives through integration: speaking the unspeakable in fragments, letting grief have language, and allowing the past to be a fact rather than a prison.

Gender, Power, and Inherited Masculinity

The story’s violence is inseparable from the gendered rules that feed it. Gordon’s entitlement is reinforced by tradition—his insistence on passing down his name, his expectation that Cora serve as a prop to his status, and his confidence that institutions will hesitate to challenge him.

The Names suggests that masculinity here is not a personality trait; it is a social permission structure. Gordon performs charm in public and control in private because those roles are rewarded differently.

The other doctors and wives at gatherings, the awkward policeman who is likely also a patient, the assumption that a respectable man’s anger must have a reason—these details show how patriarchal credibility operates. Cora learns that being believed is not only about truth; it’s about who has social standing.

The theme deepens through Gordon Jr.’s development in the path where he is named after his father. The novel studies how a boy learns what manhood is “for” in a household where cruelty is modeled as authority. Gordon Jr.’s teenage assault of Lily is not explained away, but it is contextualized as something enabled by peer culture and a hunger for male acceptance.

He discovers that violating a girl can be converted into social capital when other boys cheer and label him with affection. That is a brutal indictment of how misogyny can operate as group bonding. Later, his sobriety and guilt force him to confront the long shadow of that act, and the book treats accountability as a lived struggle, not a speech.

The counterpoint is the possibility of masculinity not built on dominance. In other paths, men like Cian or Felix represent forms of care that do not demand submission. They do not “save” Cora as a fantasy hero; they show up with steadiness, skill, and respect for her autonomy.

By setting these male figures beside Gordon’s violence, The Names separates maleness from harm while still holding patriarchal structures responsible. It also shows the costs for women in navigating these structures: Maia’s fear of being seen, Cora’s distrust of kindness, and the way even adult daughters anticipate disgust from the father’s gaze. Gender here is not a topic the characters debate; it is the water they have been swimming in, shaping what danger looks like and what freedom requires.

Complicity, Bystanders, and Institutional Failure

Cora’s suffering is not kept secret by invisibility alone; it is kept secret by the convenience of other people’s discomfort. The Names repeatedly places authority figures and neighbors near the edge of the truth and shows how rarely they step fully into it. The policeman who arrests Gordon acts uneasy, his posture shaped by professional hierarchy and the fact that Gordon is a doctor.

That dynamic illustrates a broader argument: institutions often protect reputations before they protect bodies. When Sílbhe reports abuse, the response becomes a box-ticking visit that ends the moment Cora offers a plausible explanation. The system’s threshold for action is higher than the victim’s threshold for danger, and abusers who can present as respectable exploit that gap.

The theme is not limited to official systems. Social circles also fail through silence. Other wives make a fuss of Cora at public gatherings, sensing something off but treating it like a private marital quirk rather than an emergency.

Friends suspect but hesitate, because naming abuse creates obligations: to offer shelter, to confront, to risk conflict with the abuser. Even Cora participates in the system’s failure by being forced into denial—protecting Gordon from consequences to avoid immediate harm, shielding Maia from blame, refusing help when the cost seems too high.

The novel’s moral clarity doesn’t come from scolding; it comes from showing the trap in which complicity grows. When survival depends on keeping the peace, “protecting the abuser” can become a short-term strategy even as it sustains long-term danger.

At the same time, The Names highlights what functional intervention looks like. Mehri’s steady presence, the refuge worker who arrives without interrogating Cora’s credibility, and the vet who connects her to safety all represent forms of responsibility that don’t demand perfect victim behavior. These figures do not require Cora to narrate her pain in a neat, persuasive way.

They act on what she says and prioritize reducing risk. The contrast suggests that the problem is not that abuse is unknowable; it is that many people prefer not to know. The novel quietly argues for a different ethic: believe early, act practically, and understand that hesitation can be a kind of violence when it leaves someone trapped.

Cycles of Harm, Accountability, and the Possibility of Change

The novel tracks how violence reproduces itself across generations, not through fate, but through modeling, reward, and fear. Gordon’s behavior is linked to his own father’s contempt and the culture of male legacy that teaches him he must be admired or he is nothing. That doesn’t excuse him; it explains how a man can build an identity around control. The story also shows how children raised in such a home can carry the pattern forward in altered forms.

Gordon Jr.’s assault of Lily, his later addiction, and his craving for acceptance expose how harm can be transmitted as behavior before it is understood as ethics. Maia and Julian also carry transmitted harm, though they direct it inward—through self-concealment, shame, and the conviction that they are marked by their father’s actions.

Accountability in The Names is complex because it is distributed unevenly. Gordon Sr. imagines apologies and reinventions late in life, but his imagined versions of himself function partly as escape fantasies—alternate histories where he avoids responsibility by rewriting the world.

His reflections near death show that awareness can arrive without repair. In contrast, Gordon Jr.’s path toward change involves naming his actions, sitting with disgust at himself, and choosing restraint in moments when relapse would be easy. The book positions that restraint as meaningful precisely because it is not glamorous. He doesn’t get to undo what he did to Lily; he can only refuse to add new harm.

The theme also asks what change looks like for survivors. Cora’s later independence—own home, radio, friendships, the right to open her own mail—counts as structural change, not just emotional healing.

Maia’s willingness to share memories with Julian, piece by piece, shows another form of repair: family truth replacing family silence. Julian’s realization that he is not his father is not a single epiphany; it is built through accumulated evidence of gentleness, craft, love, and the decision to return to his wife and children with urgency rather than passivity.

The Names doesn’t promise clean closure. It offers a grounded idea of hope: cycles can be interrupted when truth is spoken, when institutions and bystanders choose action, and when the next generation refuses to confuse cruelty with strength.

Love, Trust, and Intimacy After Violence

Intimacy in The Names is shaped by the long echo of fear. Cora’s reaction to a kind date, her suspicion that niceness is a trap, and her difficulty trusting men who appear safe show how abuse rewires expectation. Love becomes risky because it requires being seen, and being seen once brought punishment. Maia experiences a related fear: she hides relationships and family history, anticipating her father’s disgust even when he is not physically present.

That anticipatory shame demonstrates how abusers can continue to govern the inner lives of their victims long after direct control ends. Julian, too, struggles with closeness, afraid that romance will expose something contaminated in him—“half the genes” of a murderer, as he frames it. His honesty with Orla becomes a form of intimacy precisely because it is a refusal to present a clean, appealing version of himself.

The novel also argues that trust can be rebuilt through specific behaviors rather than declarations. Cian’s consistent presence, his teaching, and his quiet affirmation create belonging without demanding emotional performance. Felix’s role, when he reappears later, is meaningful because he meets Cora with patience and ordinary conversation, not savior theatrics.

Even sibling bonds become a site of repaired intimacy: Bear and Maia naming their shared stigma aloud, Maia later sharing childhood memories with Julian, and the family learning to speak what was once unspeakable. The contrast across the three paths suggests that love is not simply about finding the right person; it is about creating conditions where safety is real—financial independence, social support, truthful storytelling, and boundaries that are respected.

At the same time, The Names refuses to treat love as cure. Lily’s survival after the attack in Paris, the grief after Bear’s death, Orla’s exhaustion during financial stress, and Maia’s ongoing therapy all show that affection and companionship do not erase damage. Instead, love becomes a context where pain can be carried without being hidden.

The book’s late scenes emphasize ordinary acts—walking someone home, making a necklace, choosing sobriety, returning to a family house—because ordinary acts are where trust is tested. In that sense, The Names presents intimacy after violence as a practice: repeated proof that care does not have to be paid for with fear.