The Postcard by Anne Berest Summary, Characters and Themes

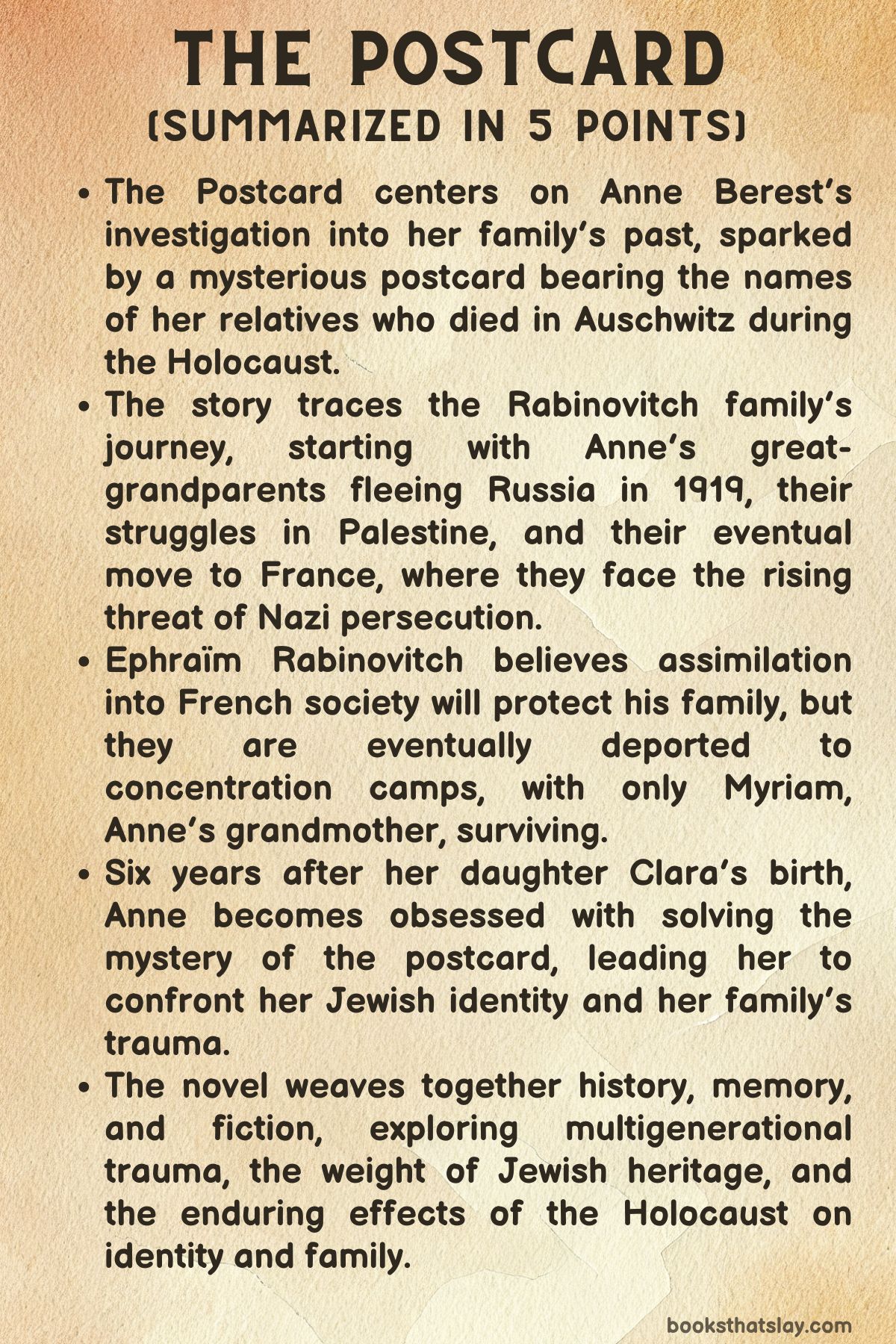

The Postcard by Anne Berest is a powerful historical fiction novel that intertwines personal memory, family history, and the aftermath of the Holocaust. Originally written in French as La Carte Postale, the book follows Anne Berest’s search for the truth about her ancestors, sparked by a mysterious postcard.

Blending fiction and memoir, Berest unravels the story of her Jewish ancestors—particularly her great-grandparents and their children—whose lives were erased by the Holocaust. The book begins with a mysterious postcard bearing only four names, sent anonymously to Berest’s mother. From this seemingly small gesture, a vast, emotional journey unfolds—spanning early 20th-century Europe to modern-day France. Through meticulous research and poignant storytelling, Berest breathes life back into lost relatives, explores what it means to be Jewish in post-war France, and investigates how silence, survival, and remembrance shape who we become.

Summary

Anne Berest’s The Postcard begins with a mystery: in 2003, her mother Lélia receives an anonymous postcard. On it are the names of four relatives—Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie, and Jacques—who perished in Auschwitz.

This cryptic message, stark in its brevity, becomes the spark for Anne’s journey to uncover her family’s hidden past. The novel unfolds in four parts, each one peeling back layers of silence, memory, and loss that span generations.

In Book I: Promised Lands, we are introduced to Ephraïm and Emma Rabinovitch, the narrator’s great-grandparents, as they navigate the shifting sands of early 20th-century Europe.

Beginning in Moscow, Ephraïm’s love for his cousin Anna is sacrificed to family expectations; he marries Emma instead. Driven by both Zionist ideals and the threat of anti-Semitism, the family flees Russia for Riga, and then Palestine. Each move reflects a mix of hope and necessity, with Emma embodying cultural resilience and Ephraïm chasing dreams of progress.

In Haifa, their Zionist aspirations falter amid harsh realities, and they ultimately relocate to France in search of stability. By the end of this section, we see the foundation laid for the next generation, particularly their daughters Myriam and Noémie.

Book II: Memories of a Jewish Child Without a Synagogue captures the experience of Myriam growing up in France during the interwar years.

Though raised in a secular, intellectual household, Myriam slowly becomes aware of her Jewish identity—not through religion, but through difference and exclusion.

She is a brilliant, sensitive child who begins to feel out of place, as casual anti-Semitism surfaces in her daily life. Her foreign-sounding name, lack of a synagogue, and the changing political tides of Vichy France all contribute to a growing unease. This part is especially poignant in portraying how children internalize fear and otherness long before they understand it.

Myriam’s perception of France—once a promised land—shifts into betrayal as danger closes in.

In Book III: First Names, Anne Berest steps into the narrative fully as the seeker.

Disturbed and intrigued by the postcard, she embarks on a deeply personal investigation to learn the stories behind the four names. Through historical archives, government records, Holocaust documentation, and her mother’s memories, she reconstructs the final years of her ancestors.

Ephraïm was a dreamer and inventor; Emma, a refined musician; Noémie, a promising scholar; and Jacques, the youngest, full of life. Each of them was arrested in France, interned at Drancy, and murdered in Auschwitz.

Berest confronts the brutal reality of French complicity in their deaths, while also wrestling with questions of memory, justice, and identity. This section is both gripping and meditative—a detective story laced with sorrow and revelation.

Finally, Book IV: Myriam is the emotional crescendo. Myriam alone survives the war, but survival is no victory. Scarred by trauma, she raises her daughter, Lélia, in a kind of emotional silence. She works humble jobs, avoids speaking of the past, and hides her Jewishness as much as she can.

Yet, in her quiet way, she resists forgetting—writing fairy tales for her granddaughter, keeping family photos, remembering birthdays.

Anne pieces together Myriam’s life through interviews, documents, and intuition, finally understanding the cost of survival. Her grandmother’s silence, once a mystery, becomes an act of mourning and protection.

In the end, The Postcard is not just a reconstruction of the past—it’s an act of resurrection. Through Anne’s tireless search, the Rabinovitch family’s names are restored to history.

The novel becomes a powerful testament to memory: fragile, painful, but necessary. In naming, Anne gives voice. In remembering, she refuses erasure.

Characters

Anne Myriam Berest (Protagonist/Author)

Anne is both the protagonist and author of The Postcard, making her a crucial lens through which the story unfolds. She begins the novel as a woman caught between worlds: one of inherited trauma from the Holocaust and her family’s past, and another as a contemporary figure who is somewhat distanced from her Jewish identity.

When Anne receives a mysterious postcard with the names of her murdered ancestors, she embarks on a journey of discovery, blending fiction, history, and memoir to piece together the family’s history. Anne struggles with her own ignorance of Judaism, which becomes a significant emotional and intellectual hurdle in the narrative.

As the novel progresses, she becomes more connected to her Jewish heritage, spurred by her relationship with a Jewish man, Georgie, and her daughter Clara’s observations about anti-Semitism. Anne’s story is as much about uncovering the past as it is about understanding how history shapes identity in the present.

By the end of the novel, Anne is haunted by the weight of multigenerational trauma. She grapples with the heavy legacy of her ancestors while trying to forge her own sense of self.

Lélia Picabia (Anne’s Mother)

Lélia is the pivotal character who initiates the storytelling by recounting the Rabinovitch family history to her daughter, Anne. She represents the generation that survived the trauma of World War II indirectly, as she was born shortly before the end of the war.

Her connection to the Holocaust is through her mother, Myriam, and the burden of that history shapes her understanding of identity and belonging. Lélia’s character is marked by a deep sense of loss, as her family was largely wiped out in the Holocaust, leaving her with fragmented memories and emotional scars.

Her decision to pass down the history to Anne reflects her desire to keep the family’s story alive, despite the overwhelming sadness it carries. Lélia’s reception of the postcard is a turning point, as it becomes a mystery that ignites Anne’s investigation, but it also deepens Lélia’s sorrow as it reopens old wounds.

Her character represents the struggle to bridge the gap between remembering and moving forward.

Myriam Rabinovitch (Lélia’s Mother, Anne’s Grandmother)

Myriam is the most significant historical figure in the Rabinovitch family, serving as a bridge between the past and present. She is the only member of her immediate family to survive the Holocaust, a fact that haunts her for the rest of her life.

Myriam’s story is one of survival, resilience, and, ultimately, loss. She spends much of the war in hiding in rural France and returns to Paris just before the war ends to give birth to Lélia.

Despite her survival, Myriam is never free from the weight of her past. She loses her husband to a drug overdose and searches tirelessly for her family after the war, working as a military translator in Germany.

Her inability to find her parents and siblings solidifies her position as a tragic figure, eternally marked by the trauma of the Holocaust. In her later years, Myriam suffers from Alzheimer’s, symbolizing her gradual loss of the past, but her action of sending the postcard before her death shows her determination to ensure her family is not forgotten.

Myriam’s character reflects the deep emotional and psychological scars left by the Holocaust. These scars transcend generations.

Ephraïm Rabinovitch (Myriam’s Father)

Ephraïm, Myriam’s father, represents the complex figure of a Jewish man striving for acceptance and assimilation in Europe during a time of rising anti-Semitism. His life is marked by his relentless desire for prosperity and recognition, which leads him to leave Palestine and seek a better life in France.

His ambition, however, blinds him to the rising dangers in Europe. Ephraïm naively believes that French citizenship and cultural assimilation will protect his family from persecution.

Ephraïm’s tragedy lies in his failure to recognize the growing threat of Hitler’s regime and the anti-Semitism that would culminate in the Holocaust. His belief in compliance and assimilation as a means of survival is ultimately futile, as his family is arrested and deported to concentration camps.

Ephraïm’s character serves as a cautionary figure, illustrating the danger of denial and misplaced hope in the face of overwhelming danger. His journey from wealth to destitution mirrors the broader experience of many European Jews who were lulled into a false sense of security before the war.

Nachman Rabinovitch (Ephraïm’s Father)

Nachman is a deeply religious man and the patriarch of the Rabinovitch family. He embodies the traditional Jewish values that Ephraïm ultimately rejects.

Nachman’s decision to flee Russia for Palestine during the 1919 purge is motivated by his strong belief in the need for a Jewish homeland and his fear for the future of Jewish people in Europe. He represents the voice of prophecy and caution, warning his children that Europe will not be a safe place for Jews.

His warnings are ignored, particularly by Ephraïm, who chooses to pursue a life of luxury in Europe. Nachman’s character serves as a foil to Ephraïm, representing the tension between tradition and modernity, faith and assimilation.

While Nachman’s choices are driven by his religious convictions, Ephraïm’s are motivated by a desire for material success and social acceptance. Nachman’s character highlights the importance of cultural and religious identity, and his warnings about Europe’s future tragically come true.

Clara (Anne’s Daughter)

Clara represents the fourth generation of the Rabinovitch family and serves as a symbol of hope and continuity. Her innocence and curiosity about her Jewish heritage spur Anne’s deeper investigation into their family history.

Clara’s observation that her school does not like Jewish people is a significant moment in the novel. It reveals that anti-Semitism is not just a relic of the past but a continuing issue that affects even the youngest members of the family.

Clara’s presence in the novel underscores the importance of passing down family stories and understanding one’s history. She is the link between the past and the future.

Her character is a reminder that the trauma and legacy of the Holocaust are still relevant and impactful, even for those who are generations removed from it.

Claire (Anne’s Sister)

Claire plays a smaller role in the novel but is crucial in one of the most emotional moments of the story. She and Anne discuss the idea that they may be the reincarnations of Myriam and her murdered sister Noémie.

Claire’s acknowledgment of this heavy burden reflects her own struggles with identity and the weight of their family’s history. Her character emphasizes the theme of multigenerational trauma, as she, like Anne, feels the pressure of living up to the legacy of their ancestors.

Claire’s agreement with Anne about their reincarnation illustrates the profound psychological impact of the Holocaust on their family. They wrestle with the past while trying to carve out their own identities.

Themes

The Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma and Memory

In The Postcard, Anne Berest delves deeply into the concept of intergenerational trauma, focusing on how the psychological scars of one generation can seep into subsequent ones, shaping the identities and psyches of descendants.

The novel explores this theme not only through the direct trauma experienced by Myriam, the Holocaust survivor, but also through the unresolved emotions and questions carried forward by her daughter, Lélia, and granddaughter, Anne.

The mysterious postcard bearing the names of family members lost in the Holocaust becomes a physical manifestation of this inherited trauma. The unresolved grief and historical weight haunt both Lélia and Anne, who grapple with their identities as Jewish women in a world where anti-Semitism persists.

Anne’s journey to uncover the truth behind the postcard becomes symbolic of her larger quest to understand her family’s painful past, and through that, to comprehend her own fractured sense of self. This struggle mirrors a broader, generational challenge: how does one honor the memory of ancestors without being completely subsumed by their tragedies?

The novel suggests that trauma can be passed down not just through stories or direct experiences, but through a lingering silence and the repression of unbearable truths. Future generations are left to piece together fragments of a broken history.

The Fragility of Identity in the Face of Historical Catastrophe

The novel intricately examines the precariousness of identity when it is subjected to the immense pressures of historical forces, particularly the catastrophic events of the Holocaust. Ephraïm Rabinovitch’s pursuit of French citizenship and his desperate hope that assimilation will protect his family reflect a tragic miscalculation of identity’s malleability in the face of systemic persecution.

His belief that his family could belong to French society if they adhered to its norms highlights the novel’s exploration of how identity can be both a choice and an illusion. The Rabinovitch family’s struggle to reconcile their Jewishness with their aspirations for acceptance in European society underscores the tension between personal and collective identity.

As history unravels their sense of belonging, they face an existential dilemma: are they French citizens, or Jewish exiles? This fragile identity is further complicated by Anne’s own disconnection from her Jewish heritage.

Raised with a diluted sense of her cultural and religious background, she must confront her ignorance and reclaim her heritage to solve the mystery of the postcard. Through this, the novel underscores that identity is not just a product of personal choices but also of historical circumstances and communal memory.

The Paradox of Silence and Voice in Holocaust Memory

One of the more nuanced themes in The Postcard is the paradoxical relationship between silence and voice in the process of Holocaust remembrance. The novel navigates the tension between what is spoken and what is left unsaid, particularly in the context of Holocaust survivors and their descendants.

Myriam, who lived through the horrors of the Holocaust, remains largely silent about her experiences. Her silence, however, does not erase the weight of her suffering but transfers it to Lélia and Anne, who are left to uncover and piece together the fragments of their family’s history.

This theme is further explored through the mystery of the postcard, which is both a cryptic message and an act of communication that arrives too late to provide any direct answers. The novel grapples with the limits of language in articulating the unspeakable traumas of genocide, suggesting that silence can sometimes be more powerful than words.

Yet, Berest also examines how descendants like Anne must find their own voices to break the cycle of silence and give shape to the suffering that remains buried. Thus, The Postcard offers a meditation on how memory is both preserved and distorted through silence, and how the act of voicing the past can be both a form of healing and a confrontation with unbearable truths.

The Ethical Responsibility of Bearing Witness Across Time

The novel deeply probes the ethical dimensions of remembering and bearing witness, particularly across generational divides. Anne’s pursuit of the truth behind her ancestors’ fate is not merely a personal journey but an ethical obligation to those who perished in the Holocaust.

Her quest highlights the moral responsibility of descendants to remember the past, especially when the horrors experienced by previous generations risk being forgotten or obscured by time. This theme intersects with the notion of historical accountability: how does one bear witness to events they did not experience firsthand?

Berest suggests that memory, even when inherited, carries with it a burden of ethical responsibility. Anne’s investigation into her family’s past is not just about solving a mystery; it is about bearing witness to the lives and deaths of those who were erased from history.

The novel portrays this act of remembering as a form of justice, a way to restore dignity to those who were stripped of it. Furthermore, it raises questions about the limits of this responsibility—how much of the past must the living carry, and at what cost to their own well-being?

Berest presents memory as both an ethical duty and a potential source of suffering, particularly when the weight of the past threatens to overwhelm the present.

The Intersection of Personal and Collective History in Shaping Identity

In The Postcard, the Rabinovitch family’s history is intricately woven into the broader collective experience of Jewish persecution in Europe. Yet the novel emphasizes how personal stories can diverge from and intersect with collective memory.

The Holocaust is a collective tragedy, one shared by millions of Jews across Europe. However, Berest focuses on how the particular details of one family’s experience shape their descendants’ sense of self.

Anne’s search for the origins of the postcard is a personal journey, but it also represents a larger exploration of how individual lives are shaped by, and contribute to, the collective memory of historical atrocities. The novel suggests that personal identity is not solely formed by individual experiences, but is deeply intertwined with the collective history of one’s community.

However, the novel also questions how much of this collective history individuals are expected to carry. Anne’s realization that she and her sister Claire might be the reincarnations of their ancestors reflects the crushing weight of this inherited history.

Yet, the novel resists a simplistic merging of personal and collective memory, acknowledging the tensions and contradictions that arise when individuals try to balance their personal identities with the legacies of their ancestors and their communities.