The Woman in Cabin 10 Summary, Characters and Themes

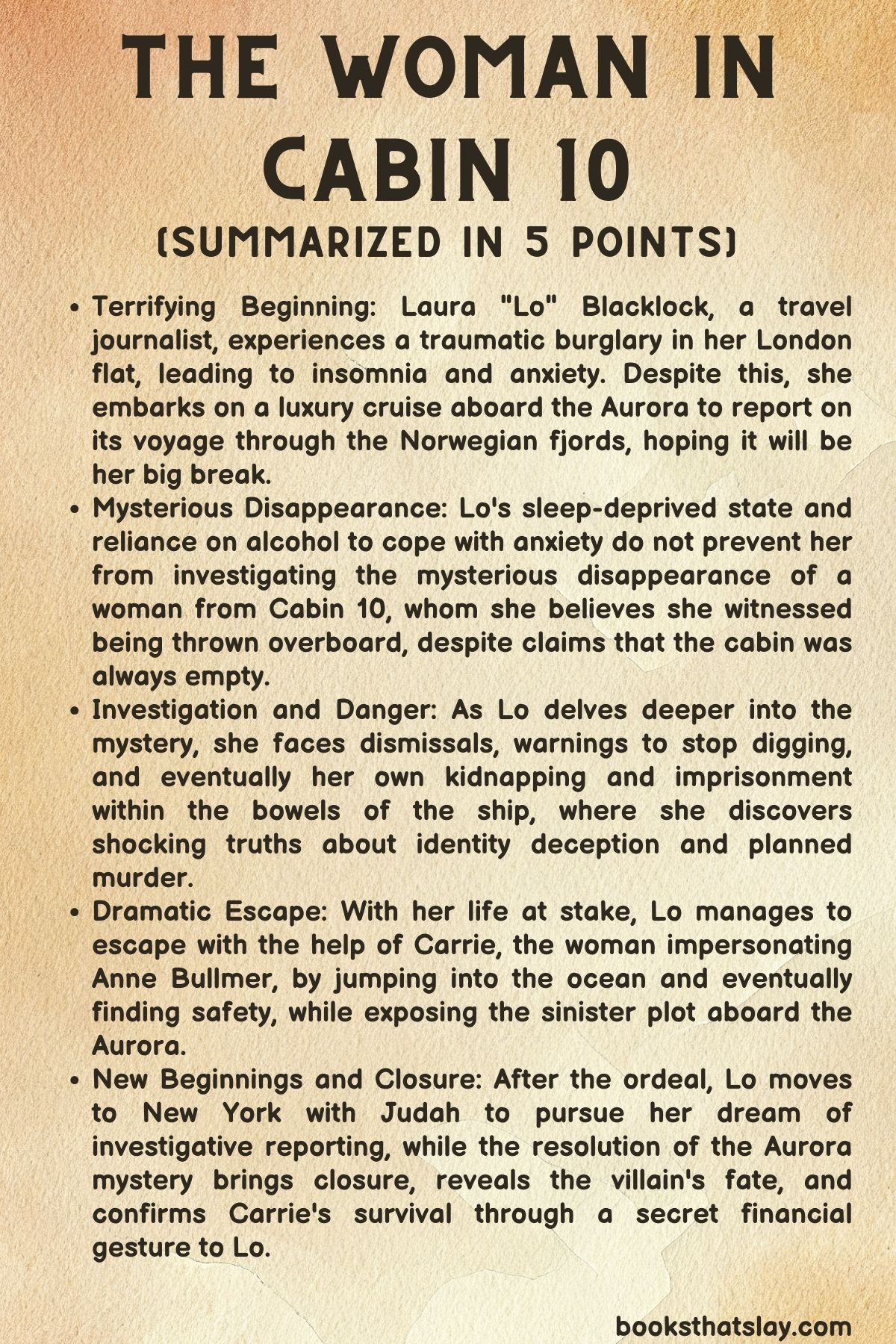

The Woman in Cabin 10 by Ruth Ware is a modern psychological thriller set on an exclusive cruise ship. Travel journalist Laura “Lo” Blacklock is sent on a once-in-a-career assignment aboard the Aurora, a small luxury liner sailing through Scandinavian waters.

Still shaken by a recent burglary at home, Lo boards the ship hoping the trip will revive her confidence and reputation. Instead, a late-night shock convinces her she has witnessed a murder. With the ship isolated at sea and her credibility under siege, Lo must figure out what happened in the next cabin before she becomes the next person to disappear.

Summary

In the heart of London, Laura “Lo” Blacklock, a passionate 32-year-old travel journalist, faces a terrifying ordeal as a burglar invades her flat, sparking a series of insomnia-filled nights and haunting flashbacks.

Despite her shaken state, Lo clings to her career-defining opportunity: to report on the maiden voyage of the Aurora, a sumptuous yacht embarking on a journey through the mesmerizing Norwegian fjords under the celestial dance of the northern lights.

Assigned by the esteemed travel magazine Velocity, Lo’s professional zeal battles her personal turmoil, further complicated by a strained relationship with her boyfriend, Judah, whose patience and sacrifices for her seem to go unappreciated.

The luxury of the Aurora offers no solace to Lo, whose sleep deprivation and anxiety are barely kept at bay by alcohol.

Her unease deepens after a bizarre encounter with a young woman in Cabin 10, who lends her mascara with a flustered demeanor before disappearing into the vessel’s opulent corridors.

The yacht’s elite gathering fails to distract Lo, especially after a disturbing incident: a scream and a splash in the dead of night, hinting at a sinister mystery when no one else seems to have noticed, and the alleged victim’s cabin is reported vacant.

Determined to uncover the truth, Lo’s investigation meets resistance at every turn, from dismissive security to the eerie disappearance of the borrowed mascara. Her inquiries lead her into the yacht’s shadowy underbelly, revealing stark disparities between the crew’s quarters and the guests’ luxury.

A chilling warning traced in steam on a spa mirror only fuels her resolve, though her credibility is questioned, marred by her coping mechanisms.

The mystery escalates when Lo is confronted by the very woman she feared dead, leading to her own capture and confinement within the ship’s bowels.

Here, in a harrowing blend of panic, starvation, and withdrawal, Lo discovers her captor’s identity: she bears an uncanny resemblance to Anne Bullmer, the ailing wife of the yacht’s owner, Lord Richard Bullmer.

A twisted tale unfolds, revealing a plot soaked in deceit, impersonation, and a love affair turned deadly, with Lo caught in the center of a stormy saga of betrayal and murder.

Carrie, as the woman introduces herself, shares a heart-wrenching narrative of manipulation and guilt, casting a new light on the night Anne Bullmer supposedly met her demise.

Lo’s empathy and investigative prowess lead to an unlikely alliance, culminating in a daring escape plan fraught with danger and a desperate leap into the unforgiving sea.

Survival brings Lo not only physical scars but a profound transformation, steering her life in a new direction alongside Judah in New York, where she embraces her dream of investigative journalism.

The mystery of the Aurora concludes with grim discoveries and an unexpected gesture from Carrie, hinting at a shadowy survival, and leaving Lo to navigate the aftermath of a voyage that forever altered her course.

Characters

Laura “Lo” Blacklock

Laura Blacklock is the story’s anxious, perceptive center, and everything in The Woman in Cabin 10 is filtered through her bruised sense of reality. Professionally, she’s a travel journalist who has been stuck doing safe editorial work, so the Aurora assignment matters intensely to her identity and future; that ambition makes her stubborn about staying on the ship even when she’s clearly unraveling.

Personally, she begins the book already fragile—on antidepressants, exhausted by a long-distance relationship, and newly traumatized by the burglary in her flat. That break-in doesn’t just frighten her; it rewires her thresholds for danger, so ordinary ship noises, a shutting door, or a shadow in a corridor become triggers for spiraling panic.

Yet Laura isn’t simply “unreliable. ” Her fear coexists with sharp observation and an instinct to connect details—floor plans, timelines, faces in photos, inconsistencies in staff stories.

What makes her compelling is that her vulnerability and her integrity are in constant friction: she doubts herself because others keep labeling her paranoid, but she also refuses to abandon what she knows she saw. Her arc across the summary is a battle to reclaim authority over her own perception in a setting designed to smother it.

Judah Lewis

Judah Lewis functions as both Laura’s emotional anchor and a quiet source of strain. He’s a foreign correspondent, brave and principled enough to work in conflict zones, which gives him a strong sense of purpose and a habit of making decisive sacrifices—like turning down a New York job so he can build a life with Laura.

But that same certainty turns into pressure; he wants commitment now, while Laura’s recent trauma makes the future feel unsafe and undefined. Their relationship is full of real affection—his worry during her silence is genuine—but also full of mismatch.

Judah is used to danger being external and manageable; Laura’s danger is internal and chaotic. When she injures him during a nightmare, it’s a brutal illustration of how far apart their worlds have become.

He represents a life she might want, yet right now can’t step into without losing herself.

Ben Howard

Ben Howard is a complicated mix of charm, entitlement, and, ultimately, unexpected loyalty. He arrives as a familiar figure from Laura’s professional and romantic past, instantly comfortable in social settings where Laura feels out of place.

His early behavior is predatory—his crude jokes and groping assault show a man who expects access and treats resistance like a game. Yet once confronted, he shifts into a confessional, apologetic mode that is real enough to unsettle Laura and the reader.

Ben becomes one of the few people who half-believes her, and he uses his observational skills to dig up unsettling details, like Archer’s “Jess” contact photo and gaps in staff narratives. This duality makes him dangerous in one emotional register and useful in another.

He is not redeemed by helping her; instead he illustrates how someone can be both a threat and an ally, depending on which part of their character is in control.

Lord Richard Bullmer

Lord Richard Bullmer is the polished engine of power aboard the Aurora, and his danger lies in how calm he is while controlling the narrative. As owner of the ship and a man used to elite circles, he has a natural authority that makes other people shrink or comply before he even speaks.

When Laura brings him her suspicions, he interrogates her like a professional investigator, not out of kindness but to establish dominance over the facts. He is careful, strategic, and emotionally unreadable, which lets him appear reasonable even while the situation grows grotesque.

In the later summary, his menace becomes explicit: he’s implied to be capable of manipulating crew, sabotaging evidence, and disposing of inconvenient witnesses. Richard embodies the kind of villainy that wears civility as armor; what terrifies Laura is not loud aggression but the sense that he can bend systems—and people—without ever raising his voice.

Anne Bullmer

Anne Bullmer is the visible absence haunting the ship. She is introduced as sick, pale, and reclusive, a woman kept out of view and surrounded by whispered explanations.

That frailty serves two narrative purposes: it makes her a symbol of vulnerability, and it also becomes a mask someone else can wear. Anne’s public identity is a delicate performance curated by her husband and the staff, so when Laura tries to reach her, she meets not a person with agency but a figure shaped by illness, exhaustion, and social control.

The later twist that Laura must impersonate her underscores how Anne’s individuality has been erased into an outfit, a posture, a role. Even in limited presence, Anne represents what happens when a woman’s reality is managed by others until she becomes almost ghost-like.

Carrie

Carrie is the book’s hidden heartbeat: a young woman whose existence is first a suspicion, then a life-or-death truth. She’s initially only a silhouette to Laura—dark hair, a Pink Floyd T-shirt, a flash in a doorway—and yet the world insists she cannot be real.

When she finally appears, she is battered but lucid, terrified but decisive. Carrie’s defining trait is survival intelligence.

She reads the ship’s power structure instantly, knows where doors lead, understands who can be trusted, and crafts a daring escape plan under extreme time pressure. Her tenderness—bonding over Winnie-the-Pooh, calling herself “Tigger,” trying to protect Laura even while trapped—reveals a person who still clings to humanity inside brutality.

At the same time, she is pragmatic to the edge of ruthlessness: she won’t flee with Laura because her odds are different, and she orchestrates a believable injury by harming herself when Laura can’t. Carrie is not a passive victim; she is a strategist cornered by a stronger predator, fighting for control of her own story.

Cole Lederer

Cole Lederer is the ship’s charismatic observer, a photographer whose camera makes him both witness and potential threat. He carries personal sadness—arriving alone after learning of his wife’s affair—which gives him a wounded openness that draws Laura in.

But his profession also makes him slippery: he sees everything through a lens that can be deleted, hidden, or manipulated. The party photo that may contain Carrie places Cole at the edge of the central mystery.

His later hand injury and the “accidental” destruction of his SD card feel too convenient, turning him into a figure of suspicion not because he is clearly guilty, but because he is so close to the truth without choosing a side. Cole illustrates the danger of neutrality in a crisis: even if he isn’t the villain, his passivity and self-interest can still serve the villain’s goals.

Chloe Jenssen

Chloe Jenssen is warmth with sharp edges. As Lars’s ex-model wife, she occupies the world Laura feels excluded from, yet she approaches Laura with friendliness and curiosity.

She is socially astute enough to ask about Laura’s bruise in a way that looks caring but also probes for gossip. Chloe also acts as a narrative mirror: composed in public, yet potentially frightened in private.

Her sudden illnesses and strategic disappearances suggest either complicity or victimhood; the summary keeps her ambiguous. She represents how privilege can be both protection and trap on the Aurora—she has access to power, but not necessarily control over it.

Lars Jensssen

Lars Jensssen is a quiet emblem of money and influence, more background presence than emotional force. He reads as controlled and confident, a man used to being listened to, and he seems to move through the ship as if it’s an extension of his social domain.

His importance lies less in personality and more in function: he is part of the elite circle around Richard, which makes him a potential enabler whether he intends to be or not. His relationship with Chloe highlights a theme of curated appearances aboard the ship—beautiful pairings that may hide imbalance or fear.

Tina

Tina is antagonistic energy in human form—restless, sharp-tongued, and willing to intimidate. She uses cigarettes, sarcasm, and social bluntness as ways to claim space on the ship, and others read her as reckless because she won’t perform gentleness.

That bluntness makes her easy to suspect, especially when Laura is seduced by the idea that the loudest person must be the most dangerous. But Tina’s true role is to complicate the moral map: she may be cruel, but cruelty isn’t the same thing as murder.

She embodies the book’s constant question of whether obvious nastiness is a disguise for guilt or merely a different style of surviving.

Camilla Lidman

Camilla Lidman is the polished face of the Aurora’s hospitality. She greets Laura by name, moves her through luxury with elegant calm, and represents the veneer the ship wants to project: effortless care, controlled delight, no mess.

That polish is not innocence; it’s training. Camilla’s calm in crisis, and her role in announcements, place her closer to the ship’s leadership than a guest might assume.

She shows how service on the Aurora isn’t only about comfort—it’s about protecting the ship’s image.

Karla

Karla is one of the few crew members whose guilt and fear leak through professional composure. She tries to stay neutral, but her conversation with Laura reveals the staff’s vulnerability: they are trapped between truth and job security.

Karla hints at the possibility of unauthorized cabin use and the crew’s terror of police involvement. She is a moral barometer for the working class on the ship—aware something is wrong, but frightened of the cost of saying so.

Her flight from the conversation is not betrayal so much as survival.

Josef

Josef is the courteous steward who guides Laura into the ship’s labyrinth and becomes part of its unsettling atmosphere. He’s described as professional and helpful, yet his movements at odd hours and implied closeness with Tina make him a figure of suspicion.

The summary positions him as potentially compromised not by malice but by access: as crew he knows the ship’s hidden routes, fire exits, and blind spots. Whether or not he is directly guilty, Josef represents how the ship’s staff can be turned into tools by those in power.

Nilsson

Nilsson serves as the institutional counterweight to Laura’s urgency. As a security or authority figure, he should be the person who protects passengers, yet he dismisses Laura as paranoid, leaning on her drinking and medication to discredit her.

His skepticism isn’t just personal bias; it reflects a system that prefers quietness over truth. Nilsson’s role intensifies the novel’s psychological tension because he doesn’t have to be evil to be dangerous—his refusal to act creates the space in which evil thrives.

Archer

Archer is a minor but pivotal node in the mystery. He comes across as another passenger moving through luxury until Ben’s report about Archer’s dropped phone reveals a contact named “Jess” with a photo matching the cabin-ten woman.

This detail makes Archer a possible link between Carrie and the ship’s hidden story. His significance is structural: he shows how a single accidental slip can threaten a carefully controlled secret.

Alexander Belhomme

Alexander Belhomme is the ship’s aging aristocratic chatter, half comic relief and half unexpected witness. He’s physically frail, socially bold, and eager to insert himself into gossip.

Yet his late-night wanderings and observations add texture to the timeline, even if he frames them flirtatiously. Alexander represents the way aging privilege can drift into carelessness—he doesn’t grasp how much danger he’s brushing against, but his casual sightings matter.

Owen White

Owen White is the soft-spoken truth-teller who brings a crucial external parallel into Laura’s world. By explaining that the owner of cabin ten missed the voyage because of a break-in and stolen passport, he unknowingly validates Laura’s growing suspicion that the burglary patterns are connected.

Owen’s quietness contrasts with the ship’s louder social players, making him feel trustworthy in a world where trust is unstable. He is a reminder that sometimes the most important facts come from the least theatrical people.

Eva

Eva, the spa receptionist, appears briefly but carries a lot of narrative weight. Her claim that the spa has only one entrance and that she was at reception the whole time is presented as an official version Laura can’t disprove.

Because she controls access to that story, Eva becomes a symbol of how environments can be built to deny possibility. Whether she is lying or simply repeating policy, her presence underscores how the ship’s infrastructure is designed to close off alternate realities.

Erik Fossum

Erik Fossum, the hotel manager onshore, is a small character whose actions show how far Richard’s reach extends. He seems ordinary and helpful at first—offering a blanket, coffee, and a phone—but when Laura overhears him contacting Richard instead of police, he becomes a sudden conduit of danger.

Erik is less a villain than a demonstration of how easily power can redirect good intentions. His brief appearance pushes Laura into the final, desperate phase of flight and exposes the fragility of safety outside official systems.

Lissie

Lissie is Laura’s friend on land, used as a point of normality and emotional shorthand. Laura’s message to her about the ship’s extravagance shows Laura trying to keep one foot in her old world, as if naming luxury to a friend might make the trip feel predictable.

Lissie functions as a contrast to the isolating paranoia of the voyage—the life Laura wants to return to if she can survive it.

Rowan

Rowan, Laura’s editor, is the voice of professional pressure. She prods Laura for updates and represents the career stakes that keep Laura performing competence even while she is terrified.

Rowan isn’t cruel; she’s simply operating inside deadlines and expectations. Her presence highlights the impossibility of separating personal crisis from professional survival for someone like Laura.

Jenn

Jenn at Velocity is pragmatic and supportive in a way that still carries quiet condescension. She offers to reassign the trip after the burglary, implying concern, but also implying Laura might not be up to it.

Laura’s refusal and insistence on going sharpen her internal conflict: she needs the career win partly because she senses how easily she could be sidelined.

Mrs. Johnson

Mrs. Johnson is the early refuge in the chaos of the burglary.

She provides tea, safety, and a landline—simple forms of care that feel almost sacred to Laura in that moment. Mrs.

Johnson’s role is small but emotionally crucial: she marks what kindness without agenda looks like, which later makes the ship’s polished “care” feel colder by comparison.

Delilah

Delilah, Laura’s cat, appears as the first spark of unease and the most innocent witness to the burglary’s aftermath. Her pawing wakes Laura; her scratching outside the locked door confirms Laura’s captivity.

Though not human, Delilah represents the domestic safety Laura loses that night, and the helplessness that later echoes through her panic attacks on the ship.

Ulla

Ulla, seen serving champagne in the hot tub scene, is another example of the ship’s staff as silent facilitators. She blends into luxury service, yet her proximity to key passengers places her within the orbit of power.

Like several crew members, she is part of the environment that can either reveal the truth or swallow it.

Themes

Trauma, Anxiety, and the Unreliable Self

From the opening pages, Lo’s recent burglary is not treated as a contained incident but as a psychological rupture that keeps reasserting itself in ordinary moments. Her body reacts before her mind can: waking to a door swinging shut triggers the same terror as the masked intruder, and a sudden scream in Judah’s apartment collapses time so completely that she attacks the person she loves.

The story uses Lo’s panic attacks, insomnia, and medication not as background traits but as active forces shaping what she notices, what she doubts, and how others interpret her. She is constantly measuring her perceptions against the fear that she is “overreacting,” a fear that grows because people around her keep suggesting it.

That tension creates a loop: trauma heightens vigilance, vigilance looks like paranoia to outsiders, and dismissal by outsiders deepens her sense of instability. Importantly, Lo isn’t portrayed as someone imagining things out of nowhere; rather, she is someone trying to keep her footing while her nervous system is on permanent alert.

Her inner narration is full of self-correction—she tells herself the ship is safe, the corridor is quiet, the door moved because of the sea—yet the very need to do that shows how safety has stopped being a baseline assumption. In The Woman in Cabin 10, trauma is shown as a kind of forced storytelling inside the mind, where every new sound must be compared to the original threat.

Lo’s struggle is therefore twofold: surviving external danger and defending her own reality against the corrosive idea that she cannot trust herself. The theme lands hardest when her credibility is questioned because of her anxiety and drinking; the reader sees how trauma can make someone both more sensitive to danger and more vulnerable to being disbelieved.

By letting Lo’s fear be messy, physical, and sometimes socially inconvenient, the novel insists that trauma is not a neat arc of recovery but a daily negotiation with memory, self-trust, and the gaze of others.

Isolation and the Fragility of Safety

Even though Lo is surrounded by luxury and people, the novel keeps returning to how easily safety can evaporate when you are cut off from reliable support. The Aurora’s design—narrow corridors, identical cabins, limited exits—creates a controlled environment that looks secure yet functions like a trap once something goes wrong.

Lo boards the ship already raw from the burglary, hoping distance and glamour might reset her, but instead the voyage amplifies her isolation: patchy internet severs her from Judah, her editor, and friends, and the absence of those anchors makes every uncertainty heavier. The ship’s exclusivity also becomes a form of social isolation.

Lo is not a rich guest but a working journalist trying to prove herself; she must network while exhausted, smile while afraid, and stay professionally “on” in a place where status rules every interaction. That imbalance means she can’t simply demand help without thinking about consequences.

Physical isolation is mirrored by emotional isolation: after Ben assaults her, she cries in her cabin alone, not because there are no people nearby but because she cannot trust who is safe. The repeated image of locked doors, removed spindles, and private verandas stresses how protection is always conditional and can be turned against you.

When Lo hears the splash next door, the sea itself becomes a symbol of isolation—endless, dark, and indifferent—making clear that on a ship, boundaries between safety and exposure are thin. Later, when she is confined and must depend on Carrie, the theme sharpens into a moral test: isolation doesn’t just endanger Lo; it forces her into choices that compromise her sense of loyalty and control.

The Woman in Cabin 10 suggests that isolation is not only being alone physically. It is being cut off from systems that confirm your reality—communication, community, and institutional trust.

In that vacuum, power concentrates in the hands of whoever controls access, and the luxuries intended to comfort become decorations on a cage.

Credibility, Power, and Who Gets Believed

Lo’s central fight is not simply to uncover what happened but to make others accept that it happened. The novel is relentless about how power shapes belief.

From Nilsson’s skepticism to the crew’s fear for their jobs, the social system on the Aurora is built to protect the ship’s reputation and the status of its owner. Lo’s account threatens that order, so the easiest response is to label her unstable.

Her bruised face, her antidepressants, her drinking, and her professional outsider status become tools for discrediting her, even though they are also evidence of vulnerability. The story shows how credibility is treated like a kind of currency: those with wealth and authority are presumed trustworthy, while those with anxiety or lower rank must “prove” themselves far beyond reason.

Richard Bullmer’s careful, almost clinical questioning reveals another dimension of this theme. Even when he appears to take Lo seriously, he controls the framing—what counts as relevant, what timeline matters, which authorities will be contacted, and when.

Lo’s dependence on his cooperation demonstrates how truth in a hierarchical setting is never just about facts; it is about access and permission. The mysterious internet outage reinforces this: controlling information flow is controlling reality.

The deletion of Cole’s photo is another pointed example. A single image could have stabilized Lo’s claim in the eyes of others, so removing it restores the dominant narrative.

The theme becomes even more charged with Carrie’s existence. Carrie is literally hidden inside an official identity, and her survival depends on staying unbelievable.

The system is so ready to accept the “clean” story of Anne Bullmer’s illness that it cannot accommodate the messy truth of another woman in that cabin. In The Woman in Cabin 10, belief is not shown as a neutral act of listening but as a political decision influenced by class, gender, mental health stigma, and self-interest.

Lo’s eventual determination to report what she knows, even when it makes her look irrational, becomes an act of resistance against a world that rewards silence and punishes inconvenient witnesses.

Gendered Threats and the Normalization of Violation

The danger Lo faces is not limited to a single villain; it is part of a broader pattern of how women’s bodies and boundaries are treated throughout the story. The burglary is an invasion that leaves her feeling helpless inside her own home, but the novel quickly shows that this helplessness is socially reinforced.

Ben’s assault in the corridor is especially revealing because it happens in public space, after drinks, in a tone he frames as joking. His immediate shift to apology does not erase the reality that he felt entitled to touch her, and Lo’s reaction—kneeing him, sobbing, then still having to manage his feelings—captures the exhausting calculus women are forced into when asserting boundaries.

Chloe’s assumption that Lo’s bruise may be from a relationship, while sympathetic, reflects how normalized male harm has become; the possibility is so common that it’s the first explanation offered. On the ship, women are also positioned as decorative extensions of male power: Chloe as a glamorous spouse, Anne as a fragile figure kept out of sight, Tina as someone navigating influence through ruthlessness.

Each woman is read through a lens shaped by male expectations, and deviations from that lens invite suspicion. Carrie’s predicament brings the theme to its darkest point.

She is treated as disposable within a system of male control, and her forced role as Anne demonstrates how women can be turned into interchangeable surfaces—identity as costume, body as cover story. The threat is not only physical violence but also erasure and containment.

Even Lo’s credibility is gendered: being emotional or frightened is used against her, and her insistence on danger is treated like hysteria. The Woman in Cabin 10 argues that gendered violation is often hidden behind manners, luxury, and plausible deniability.

The men who harm or dismiss Lo do not need to be openly monstrous to be dangerous. Their advantage lies in how easily society excuses them, and how quickly women are asked to doubt themselves for naming what happened.

Identity, Performance, and Survival

Lo spends much of the novel performing versions of herself for different audiences: professional journalist at dinner despite exhaustion, polite guest despite fear, capable partner despite resentment. This constant self-management becomes a survival tool but also a source of strain, because performing competence can make it harder to admit vulnerability.

On the Aurora, where status is theatrical and every interaction feels staged, identity becomes something you put on like formalwear. Lo’s assignment is a career opportunity, yet it also forces her into a role that conflicts with her private reality.

She must be observant but not disruptive, curious but not “difficult,” and grateful for access even when access is being used to control her. The theme sharpens in the later escape sequence, where identity becomes literal disguise.

Carrie asks Lo to become Anne, not just by wearing silk but by moving slowly, inhabiting the confidence of someone with power. The act is terrifying because it shows how much social identity depends on surface cues and how quickly people accept a role if it aligns with their expectations.

Carrie’s shaved head, hidden under a scarf, reveals her own identity as a carefully managed secret, and her decision to stay behind shows the painful limits of reinvention within oppressive systems. Lo’s discovery of the handgun is another moment tied to identity: she chooses not to take it because she doesn’t see herself as someone who can use it, and because she understands how it would rewrite her in the eyes of authorities.

Survival here is not only about escaping the ship; it is about choosing which version of yourself you can live with afterward. The Woman in Cabin 10 treats identity as both fragile and strategic.

Under pressure, people become masks for one another, reputations override truths, and survival may require acting a role you never wanted. Yet the novel also suggests that performance can be a form of agency.

Lo’s refusal to surrender her core sense of what she saw, even when she is forced to play along in the short term, is the point where identity shifts from something imposed to something defended.