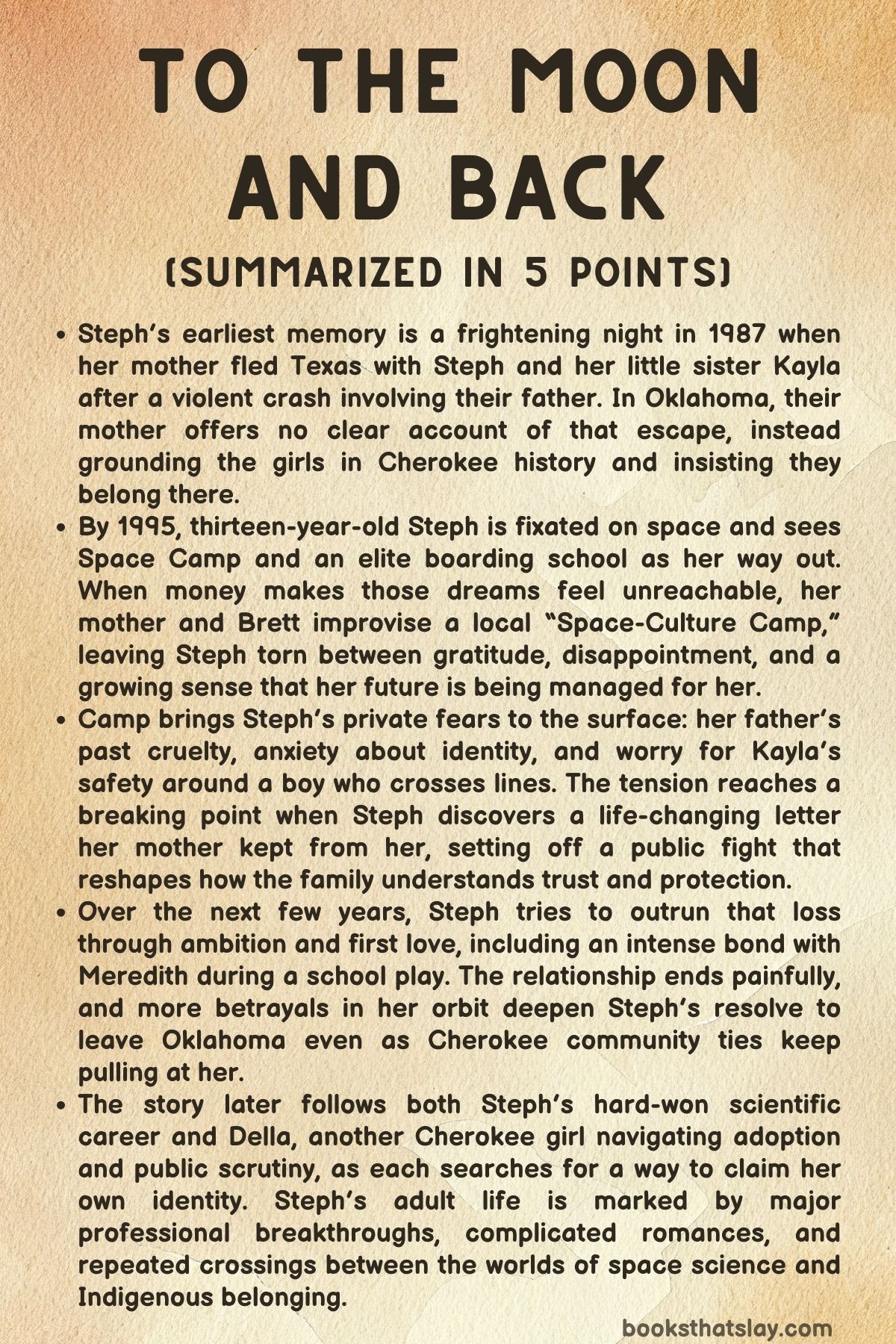

To The Moon and Back Summary, Characters and Themes

To The Moon and Back by Eliana Ramage is a coming-of-age novel that follows Stephanie “Steph,” a Cherokee girl whose earliest memory is escaping Texas with her mother and sister after a violent night with her father. Growing up in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, Steph clings to a dream of space—astronauts, rockets, and a life far beyond the limits she feels around her.

But family trauma, cultural belonging, love, ambition, and betrayal keep pulling her back to Earth. The book traces Steph from adolescence into adulthood as she tries to choose who she wants to be without losing where she comes from.

Summary

Steph’s first clear memory is a terrified drive out of Texas in 1987. Her mother barrels through the night with Steph and her little sister Kayla in the back seat, all of them shaken and bleeding from a car crash that isn’t really an accident.

Steph sees her father left behind, badly injured near the road. No one explains much afterward.

In Tahlequah, Oklahoma, their mother rebuilds a life by repeating stories of Cherokee ancestors and the long history of survival and removal. The lesson is simple: they belong here now, and they will not run again.

By 1995 Steph is thirteen and restless. Tahlequah feels too small for her hunger and fear.

She wants NASA, space science, and a future that escapes the shadow of her father. She fixes her hopes on two things: attending Space Camp in Huntsville and winning admission to Phillips Exeter Academy.

She studies obsessively, steals pay stubs to fill out financial aid forms, and counts the days until letters arrive. When her mother announces there can be no real Space Camp, Steph tries not to cry.

Instead, her mother and Brett—her mother’s boyfriend and a Cherokee language teacher—have invented a local “Space-Culture Camp” in a middle-school gym. It’s free, well-meant, and a disaster for Steph’s heart.

Camp is held together with taped paper planets, a padded garbage can used as a “capsule,” and improvised games. The kids roll down a hill pretending to be launched into orbit, and later go to a creek instead of any real training facility.

At the creek, conversation turns to identity. Campers rattle off their ethnic fractions and Cherokee ties.

When someone asks Steph what she is, her body goes rigid. She dives underwater and flashes back to Texas: her father shining a flashlight into her face, calling it a lesson about quasars and cosmic threats, teaching her that the universe is dangerous and that she must always be ready to run.

Back at camp she overhears Kayla and a boy named Daniel mocking her for her space obsession. Steph confronts them and notices Daniel touching Kayla in a way that makes her uneasy.

She pulls Kayla away, but Kayla snaps that Steph is just jealous and storms off. Steph feels alone on every front: her dream mocked, her sister slipping away, and Exeter still silent.

Brett tries to draw her into the Cherokee lessons woven into camp, gently asking why she keeps holding back. Steph can’t tell him that each lesson feels like another reminder of staying put.

On the final day they visit a Tulsa climbing gym for a simulated spacewalk. Partners climb to match English and Cherokee vocabulary cards at the top.

Steph plans to tell her mother about Kayla dating Daniel, but Kayla begs her not to. When Steph runs to buy her mother a soda, she searches her mother’s purse and finds a crumpled Exeter acceptance letter offering a full scholarship.

The deadline passed months ago. Her mother hid it.

Steph caves in on the spot, sobbing in secret, then returns pretending she’s fine.

Halfway up the climbing wall Steph confronts her mother. Her mother admits she “had to” stop Steph from leaving, insisting Steph’s life isn’t fully hers yet and that she’s protecting them from dangers Steph doesn’t understand.

The argument spills into chaos: Steph scrambles upward to get away, her mother freezes in panic, Brett lowers her down, campers fight, ropes tangle, and a nearby birthday party looks on. Someone sneers at the Cherokee kids, and a furious Meredith—an intense new girl at camp—curses them out.

Camp ends early, in humiliation.

Steph finally tells Kayla the truth: Exeter was real and their mother destroyed the chance. Kayla, stunned, backs her quietly.

Life continues anyway. Steph frames the acceptance letter on the living-room wall like a small memorial.

Two years pass. She improves her Cherokee, stays in Tahlequah, and slowly lets NASA drift farther from reach.

In 1997 Steph auditions for a school play about a Cherokee family on the Trail of Tears and is cast opposite Meredith. Rehearsals grow into something electric—holding hands onstage, kissing backstage, sharing a private world that feels truer than anything Steph has known.

Steph falls hard. After the final show Meredith goes to meet her boyfriend, Daniel.

When Steph tries to name what they’ve been to each other, Meredith panics, calls it a misunderstanding, reminds Steph she’s a girl, and demands silence at school. Steph is wrecked.

Soon the family travels to a Cherokee Tri-Council meeting in North Carolina. Steph hopes to visit Duke University for a public lecture by astrophysicist Dr. Lars Carson. She slips into the dark hall, hungry for any doorway back to space.

The talk begins with wonder—a distant gamma-ray burst seen by Hubble, a star collapsing into a black hole after billions of years of travel. Steph is caught by the scale, but loses the thread as the science deepens.

During questions she asks about time travel and black holes, quoting Stephen Hawking. Dr. Carson brushes her off bluntly as science fiction. The dismissal hits her like a slap.

She leaves shaky, as if the smartest room in the world has no place for her.

Because the lecture runs long, they arrive late to the Kituwah mound ceremony and miss it. Their mother walks alone into the mud, kneels, and prays in darkness.

Steph realizes how much her mother needs this history to stay upright. In the car her mother says Steph cannot live as if she’s separate from her people; she has to meet them halfway.

By 1999 Brett is caught sleeping with Beth, a family friend, even as he campaigns for principal chief. Steph works at the Cherokee Heritage Museum’s living-history village, trying to earn money to escape.

When a snake bites her coworker, Steph is left alone with a tour and starts inventing wild stories to entertain a little boy. Elders and visitors laugh along, but the supervisor later fires her for embarrassing the exhibit.

Furious and desperate, Steph tries to steal baskets from the gift shop to sell. Meredith catches her, refuses to cover for her, and tells Steph she’s selfish and blind to how Cherokee artists survive.

Steph walks out more determined to leave.

In 2000 the story shifts to Della “Emma” Owens, a Cherokee teenager adopted by Mormon parents in Utah after a famous custody fight. Each year she visits her biological father, Matthew Owens, in Oklahoma.

She sees relatives, sits with a grandmother lost to Alzheimer’s, and absorbs a culture she barely knows. At the county fair strangers shout “Baby D” and photograph her, and she flees with Matthew to the truck.

She remembers how the adoption bypassed the Indian Child Welfare Act and how courts kept her in Utah. Now, on the edge of college, she decides her identity will be her own choice.

She flies back west, carrying both grief and agency.

Years later Steph is an adult astronomer and geologist, explaining supernovae at conferences. She falls into a serious relationship with a physicist, imagines a life together, and buys an emerald ring to propose.

The night she plans to do it, colleagues catch a supernova in the act of exploding using data Steph also had. She missed it.

At dinner her partner announces she’s taken a job at Yale and is leaving. Steph doesn’t propose.

She collapses into a long depression, and Kayla flies in from Boston to rescue her, clean her apartment, and try to get her help. Steph refuses therapy out of fear it will ruin future astronaut applications.

She later admits she pushed her partner away not only from heartbreak but from rage at herself for missing the discovery.

Time moves in flashes: Steph studies and works abroad, stays lonely and driven, and keeps orbiting ambition. In 2014 the family reunites in Italy near Mount Vesuvius, where Steph is working on an evacuation-drill project.

Old tensions flare, and their mother finally tells painful truths about her own childhood and how violence echoes through generations. That night Felicia, Kayla’s daughter, runs away from the hotel to sit alone on the volcano.

Steph finds her, and they talk under the stars. Felicia urges Steph to stay close to family even if she chases the sky.

Steph is eventually selected as a NASA astronaut candidate and joins a Mars-habitat simulation on Mauna Loa. Protesters opposing a massive telescope on sacred Mauna Kea approach the dome.

Steph learns Kayla and Felicia are camped with the land protectors. She sneaks out in her suit to meet them, and the sisters argue by firelight about duty, science, and who gets to claim the future.

Steph walks back at dawn unsure of her place in any world.

Later, injured during training by a shark, Steph returns home on crutches. Over waffles at a crowded coffee table, she finally asks why their mother stayed with their father.

Their mother tells the full story: he drove them off a ridge on purpose, and she fled the wreck believing she was leaving him to die so she could save her daughters. She had been packed to escape for months.

That night she chose it.

In the calm days after, Steph sends an apology to Della for hurting her years earlier. Della, now a marine scientist and new mother, accepts it and shows Steph what life can look like after loss.

Then disaster strikes: their mother collapses from a heart attack and never regains consciousness. Steph and Kayla sit beside her, consent to remove life support, and hold her as she dies.

At the funeral Brett admits the telescope he once gave Steph was bought by their mother, a quiet investment in her dream all along.

Steph apologizes to Kayla for past betrayals, and Kayla forgives her. Steph returns to training, is assigned an International Space Station mission, and tours Cherokee homelands with Kayla to honor their mother’s hopes.

Much later, after multiple missions and finally a flight to the moon, Steph looks down from orbit, finds the light of her mother’s old house, and imagines Kayla keeping it on—an anchor beneath her, steady as a star.

Characters

Stephanie “Steph”

Steph is the emotional and narrative center of To The Moon and Back. From the start, her life is defined by a split between flight and belonging: she carries the trauma of escaping Texas, yet also dreams of escaping Oklahoma for space.

That tension becomes her core engine. As a teenager she is fiercely intelligent, driven, and resourceful—stealing pay stubs, chasing Exeter, clinging to Space Camp—because she believes excellence is her only exit route.

But her ambition isn’t purely self-invention; it is also a survival strategy shaped by her father’s terrorizing “astronomy lesson,” where the cosmos becomes a warning that she must always be ready to run. Steph’s relationship to Cherokee identity is similarly conflicted: she loves the stars, but struggles to “meet her people halfway,” feeling both guilt and distance.

That disconnection fuels moments of panic and defensiveness, like her reaction at the creek or her inability to fully commit to cultural learning during camp. In adulthood, Steph achieves the scientific life she once worshipped, yet the same intensity that drives her leads to isolation, missed opportunities, and collapse—the ignored supernova data and the breakup show how ambition can hollow out her relationships and self-worth.

Her later arc is about integrating rather than escaping: returning home injured, asking hard truths, apologizing to those she hurt, and finally learning that her dream of space doesn’t have to mean severing ties. By the end, she becomes someone who can carry both orbit and homeland inside her, letting love and accountability coexist with her reach for the sky.

Kayla

Kayla is Steph’s younger sister and her closest mirror, but one that reflects a different survival style. As a child she is carried through the wreckage of Texas, and as a teen she often seems to side with peers or push against Steph’s seriousness, mocking her space obsession and resenting her protectiveness.

Yet Kayla’s defiance is never cruelty for its own sake; it’s a way of claiming autonomy in a family where fear and secrecy dominate. Her relationship with Daniel, her indignation at Steph’s near “tattling,” and her later sharp reactions to Steph’s probing questions all show how fiercely she guards her own choices.

At the same time, she’s also the most reliable responder in moments of crisis. When Steph spirals in California, Kayla crosses the country, cleans her apartment, feeds her, and tries to push her toward care, becoming the practical caretaker Steph cannot be for herself.

Adult Kayla channels her intelligence into community and activism, most powerfully in Hawai‘i, where she places moral duty and cultural solidarity over Steph’s NASA dream. Their argument by the fire reveals Kayla as someone who believes belonging must be lived, even at cost, and who sees self-exile as a kind of betrayal.

Yet she is never rigidly unforgiving: she deletes the adviser’s Facebook comment to protect Steph’s privacy, supports her sister’s grief, and ultimately forgives her for the Hawai‘i betrayal. Kayla’s final role is both anchor and light-keeper; she insists on home as a living responsibility, but also chooses love over resentment, making reconciliation possible.

Steph and Kayla’s Mother

Steph’s mother is a woman shaped by generational harm, Cherokee history, and the specific terror of domestic abuse. Her defining trait is protective control: she loves her daughters intensely, but her love expresses itself through guarding, withholding, and anchoring them in place.

The flight from Texas shows her at her bravest and most ruthless, leaving an injured husband behind because staying even one more minute could mean losing her will to escape. Afterward she remakes reality for her daughters through story, especially Cherokee stories of Removal and survival, turning history into a promise that Oklahoma is where they belong and where danger will no longer chase them.

This protective impulse becomes damaging when she hides Steph’s Exeter acceptance. Her “had to” is not simple selfishness; it comes from fear that the world outside, like their father, will destroy her child, and from a buried belief that Steph’s life still belongs partly to family survival.

She embodies the paradox of trauma parenting: the same instincts that save children can also trap them. Over time, though, she grows into painful honesty, finally telling the true story of the crash, explicitly rejecting the excuse that suffering licenses harm, and trying to model moral clarity for Felicia.

Her need for Kituwah and for cultural ceremony shows that she too is trying to heal through belonging, even if she cannot always articulate it without anger. Her death is a rupture that forces the sisters into intimacy and truth, and the revelation that she bought the telescope for Steph reframes her not as the enemy of dreams, but as a flawed guardian who wanted both safety and wonder for her daughter.

Steph’s Father

Steph’s father is largely present through memory and consequence, yet he casts a long shadow. He is physically and emotionally abusive, and his abuse takes a particularly insidious form: he weaponizes knowledge and fear.

The childhood “astronomy lesson” is not a tender teaching moment but a domination ritual, turning space into apocalypse, shining light in Steph’s face, and instilling the idea that catastrophe is always imminent. His final act of driving off the ridge on purpose crystallizes him as a man whose rage is lethal and whose control extends even to self-destruction.

Losing his leg in the crash makes him a figure of tragedy as well as menace, and the mother’s later reflections suggest he had redeeming qualities, but the book refuses to soften the moral line: his suffering never excuses what he did. He functions in the story as the origin of the family’s flight reflex, the reason Steph equates love with danger, and the hidden wound underneath her lifelong readiness to run.

Brett

Brett begins as a hopeful bridge between worlds: he is the mother’s boyfriend, a teacher, and a Cherokee language advocate who tries to connect space wonder to cultural grounding through Space-Culture Camp. For Steph, he is initially an ally to her dream life, the adult who shares her fascination with the stars and offers a gentler, more playful form of guidance than her mother.

That bond makes his betrayal devastating. When Steph discovers him with Beth, it feels like the collapse of her last safe adult relationship and confirms her belief that attachment is dangerous.

Yet Brett is not a one-note villain. His rally speech about gadugi and strengthening families shows he sincerely believes in communal responsibility, and his later appearance at the funeral reveals lingering care and humility.

The telescope revelation is crucial: it shows Brett as an imperfect conduit for the mother’s love, someone who was part of Steph’s dream even when he didn’t fully embody it. He represents the complexity of community figures—capable of real mentorship and real harm, admired and resented at once.

Daniel

Daniel is a minor but sharp-edged figure who embodies adolescent cruelty and boundary violation. At camp he mocks Steph’s ambition, reinforcing her insecurity about being different, and his inappropriate touching of Kayla signals a casual entitlement to others’ bodies.

He later reappears as Meredith’s boyfriend, which turns him into a symbol of the heterosexual path that excludes Steph and denies the intimacy she thought she had found. Daniel never needs deep interiority because his role is structural: he is the person who helps sever Steph from both her sister during adolescence and her first love during young adulthood, a reminder of how easily Steph is pushed outside the circle.

Meredith

Meredith is one of the most painful catalysts in Steph’s coming-of-age. She arrives at camp as serious, bold, and unafraid to confront disrespect, which makes her feel like someone who might understand Steph’s intensity.

Their relationship during the school play is tender and electric, built through shared performance and physical closeness that lets Steph imagine a life where love and identity might finally align. Meredith’s refusal afterward is complicated: she frames the intimacy as a misunderstanding, insists on her boyfriend, and avoids Steph at school.

Whether this is denial, fear, or genuine difference in feeling, the effect on Steph is the same—shattering and humiliating. Meredith later confronts Steph at the museum theft scene with blistering honesty, naming Steph’s self-absorption and refusing to protect her at the cost of Cherokee artisans.

That moment reveals Meredith as not merely a lost love but a moral counterweight. She stands for grounded accountability and for the limits of Steph’s escape fantasy.

Even when she wounds Steph, she also presses her toward seeing the people around her as real, not just obstacles or scenery in her launch story.

Beth

Beth is the quiet disruptor of Steph’s fragile sense of trust. At first she seems almost benign, even kind, giving Steph a moonstone and reassurance after the camp chaos.

But her affair with Brett makes her a focal point of betrayal, less because of her personal malice and more because she becomes the face of another adult bond collapsing. She shows how harm can come from those who look gentle, reinforcing Steph’s fear that safety is an illusion.

Beth’s presence also underscores a theme of tangled intimacy in small communities, where personal mistakes ripple into the lives of children watching from the margins.

Dr. Carson

Dr. Carson functions as the embodiment of institutional coldness.

His lecture dazzles Steph at first, reviving her sense of cosmic wonder, but his flat dismissal of her black-hole question punctures her with shame. Importantly, he doesn’t mock her directly; he simply refuses imagination, treating curiosity as naïve science fiction.

For Steph, who has built her identity on the belief that knowledge can save her, this moment is a spiritual humiliation. Carson represents the gatekeeping edge of science—the way brilliance can be paired with incuriosity about the human need behind questions.

His role is small, but the scar he leaves is large, contributing to Steph’s growing sense that the path to space may not want someone like her.

Will

Will is a practical authority figure at the Cherokee Heritage Museum and a mirror of how community institutions can police representation. When Steph improvises stories to entertain a boy during the snake emergency, she isn’t trying to mock her culture; she is overwhelmed, alone, and desperate to keep the tour alive.

Will fires her anyway, naming the real danger: her exaggerations feed stereotypes. He stands for a hard, necessary boundary—one Steph experiences as rejection because she is already raw and trying to flee.

Will’s presence pushes the theme that cultural survival requires discipline, not just pride, and that Steph’s escape impulse can lead her to careless harm.

Della “Emma” Owens

Della, later reclaiming herself as Della, is a parallel protagonist who refracts Steph’s struggle through another lens. Adopted into a Mormon family in Utah and made public spectacle as “Baby D,” she grows up split between imposed identity and ancestral claim.

Her Oklahoma visits are tender and bleak: she feels love for her biological father and relatives, but also the crushing weight of being a symbol rather than a person, especially at the county fair when strangers chant her nickname and photograph her. Della’s interiority is defined by choice—after years of legal and cultural theft, she decides her identity will no longer be negotiated by courts or headlines.

Her later life as a marine scientist and adoptive co-parent shows a grounded, self-authored belonging that Steph envies and admires. When she accepts Steph’s apology, she models a mature form of healing: she does not erase the hurt, but she also refuses to let it dictate her future.

Della stands for the possibility of reclaiming heritage without surrendering autonomy.

Matthew Owens

Matthew is Della’s biological father and a portrait of constrained love. He welcomes Della warmly each year, tries to give her family access, and carries his own grief quietly.

Yet he is also a man whose earlier decisions were used against him by a system eager to remove a Native child from Native custody. His helplessness at the fair episode emphasizes how little power he has over the narrative surrounding his daughter.

Matthew embodies the personal cost of structural injustice: he is not defined by failure of love, but by being outmaneuvered by legal machinery that treats his consent as a technicality rather than a living bond.

The Physicist

Steph’s unnamed physicist partner is her adult love story and one of the clearest tests of her emotional growth. She is brilliant, committed to her own career, and yet unusually flexible in how she imagines shared life.

Her willingness to shape plans around Steph’s astronaut dream—moving, marrying legally, even offering to step back from her own career if needed—shows a depth of love and pragmatism Steph has never known. Her departure for Yale is not betrayal but self-respect, a boundary drawn after living too long in Steph’s orbit without being fully met.

The physicist reveals Steph’s core flaw at that stage: she can love, but she still treats love as secondary to ambition and fear. The breakup exposes that Steph’s devastation is tied not only to romance but to perfectionism and missed professional glory.

This partner’s role is to show what Steph could have had if she were able to stay, and to underline the cost of always choosing the sky over the person beside her.

Nadia

Nadia is Steph’s closest adult friend, fellow astronaut candidate, and emotional sparring partner. She brings levity into Steph’s intensity, teasing her about injuries and refusing to let her sink fully into isolation.

Nadia is also morally direct. She pushes Steph toward apology and accountability, naming the ways Steph’s actions harmed Kayla and the protest movement.

At the funeral she arrives despite her own injury, cooks, comforts, and integrates herself into Steph’s family grief without making it about herself. Nadia stands for chosen family within high-pressure ambition, a reminder that competence and care can coexist.

She also represents the kind of astronaut Steph is becoming: not merely technically elite, but humanly tethered.

Jason

Jason, Kayla’s husband, occupies the background as a steady but slightly tense presence. His disagreements with Kayla over her social-media platform and family privacy show how the modern pressures of visibility complicate marriage and parenting.

He’s not central to Steph’s self-story, but he helps frame Kayla’s adulthood: she is not only a sister and activist, but also a partner navigating ordinary strains. Jason functions as the domestic counterpoint to Steph’s world of missions and domes, reinforcing how different their paths have become.

Felicia

Felicia is Kayla’s daughter and the generational hinge of the family. She idolizes Steph’s astronaut life with a child’s joy, hugging her injured aunt and delighting in drama, but she is also perceptive beyond her years.

Her terror at Pompeii and her flight to Vesuvius express a need for space, quiet, and agency that echoes Steph’s own childhood hunger to escape. In their summit conversation she becomes a truth-teller, urging Steph to show up for Kayla and to see the struggles her sister is hiding.

Felicia’s presence shifts Steph from self-focus to caregiving; she allows Steph to practice gentleness without the old rivalry or defensiveness that marks her bond with Kayla.

Mark

Mark is a brief but meaningful figure at the Mauna Kea protest camp. He recognizes Steph through her suit, grounding her in the reality that her public identity has consequences within Native political life.

His presence highlights Steph’s liminal position: she is both celebrated as a Native astronaut and implicated in institutions contested by Native land protectors. Mark represents the watchful community voice that sees her not only as an individual dreamer, but as part of a larger collective struggle.

Aziz

Aziz is one of Steph’s fellow trainees and part of the professional ecosystem she lives in. Though he remains in the background, his inclusion signals Steph’s eventual movement into a collaborative, diverse astronaut corps.

He represents the steady continuation of her mission life after personal catastrophe, a reminder that the world of training does not pause for grief.

Alicia Soderberg and Edo Berger

Alicia and Edo are minor characters, but they embody the ruthless impartiality of scientific timing. Their discovery of the exploding supernova is not personal to Steph, yet it becomes a personal apocalypse for her because it reveals how proximity to greatness is not the same as seizing it.

They function as the living proof of what Steph fears: that someone else will notice the moment she misses. Their role intensifies the book’s meditation on ambition, chance, and the cruelty of missed windows.

Sam

Sam appears through Della’s adult life as her co-parenting partner and longtime friend. Their family structure—rooted in closeness, trust, and deliberate choice—shows another model of belonging outside traditional scripts.

Sam’s presence reinforces Della’s theme of self-authored identity and care, and quietly contrasts Steph’s earlier inability to accept stable love.

Steph’s Grandmother and the Cherokee Elders

Steph’s Alzheimer’s-stricken grandmother and the elders at the museum and meetings represent memory as both burden and lifeline. The grandmother’s confusion and clinging grief dramatize what it means to be separated from kin and culture, while the elders’ laughter during Steph’s improvisation reminds her that humor and storytelling are also part of survival.

They serve as the living link to historical trauma and continuity, pressing Steph to understand that identity is not only about personal ambition but about carrying and reshaping inherited stories.

Themes

Intergenerational trauma and the logic of survival

From the opening flight out of Texas to the final return to Tahlequah, the story tracks how trauma is carried forward not just as memory but as a set of instincts. Steph’s mother does not give her daughters a tidy narrative of what happened with their father; instead she lives in a posture of preparedness, a life shaped by the certainty that danger can reappear without warning.

Her stories about Cherokee ancestors and Removal are not historical trivia for her children. They are a way to pin the family to ground that feels safe, and to explain why staying close to home matters more than any opportunity elsewhere.

Steph experiences that as suffocation, but the later revelation about the crash shows the mother’s choice as a survival act built on years of fear, love, and calculation. The mother’s secrecy about Exeter fits into the same pattern.

She is not simply controlling; she is trying to prevent her daughter from stepping into a world she believes she cannot protect her from, because protection has been the mother’s only reliable tool against catastrophe. Steph’s flashback at the creek, where a childhood “astronomy lesson” turns into terror under her father’s manipulation, shows trauma also shaping how she encounters the universe.

Space is both wonder and threat, a place tied to the father’s warnings about apocalypse and running. Even Steph’s adult collapse after missing a supernova discovery echoes the childhood lesson that safety depends on vigilance.

The narrative keeps returning to the cost of survival strategies that once worked: silence, overcontrol, and constant readiness save lives, but they also block growth and intimacy. Healing arrives not through forgetting, but through naming what happened and letting relationships hold the truth without breaking.

When the mother finally explains why she stayed and why she fled, she hands the next generation a different inheritance: not the trauma itself, but the language to resist it.

Cherokee identity, belonging, and the pull of departure

Steph’s desire to leave Tahlequah is never just a teenage itch. It is tied to a belief that her future requires distance from the place her mother insists is home.

The tension between those positions runs through the book as a question of what belonging demands. The improvised Space-Culture Camp stages that conflict in miniature: space science and Cherokee knowledge are placed side by side, but Steph feels them as competing routes to selfhood.

She wants NASA; the camp asks her to claim language, stories, and lineage. The creek scene, with its casual listing of “fractions,” shows how identity can become a performance policed by peers, creating shame instead of connection.

Steph’s panic there is not only about being questioned; it is about feeling that her obsession with the stars makes her less Cherokee in other people’s eyes, and maybe in her own. Yet the book refuses a simple either-or.

The trip to Kituwah shows Steph recognizing that the mother’s bond to land and history is not backward-looking nostalgia; it is a way to survive erasure. Later, the Mauna Kea protest situates Steph’s astronaut ambition inside another Indigenous struggle over sacred ground.

Kayla’s anger that Steph “sets herself apart” is also a critique of how institutions reward individual ascent while communities bear collective wounds. Even in adulthood, Steph cannot fully separate her career from her people’s claims, because her success becomes symbolic and contested.

The final speaking tour through Cherokee homelands shows a tentative reconciliation: Steph’s flight to space is reframed as carrying her mother’s hopes rather than rejecting them. To The Moon and Back presents identity as something negotiated across places and obligations, not a static label.

Home can be a refuge, a duty, and a site of conflict all at once. The story’s movement suggests that belonging is not proved by staying or leaving, but by returning with honesty and accepting that being Cherokee can include ambition that reaches beyond the horizon.

Ambition, control, and the fragility of opportunity

Steph’s drive toward space is portrayed with both admiration and critique. Her childhood dream is pure and animating, but it quickly encounters a world where access depends on money, deadlines, and adults who control the gates.

The thousand-dollar Space Camp fee is a blunt reminder that talent alone does not open doors. Her mother’s hidden Exeter letter becomes the defining wound because it turns a rare opening into a loss that Steph did not choose.

What makes this betrayal so devastating is that it is not random misfortune; it is a deliberate act from the person she needs most, and it teaches her that desire can be thwarted by someone else’s fear. In the years after, Steph keeps the letter on the wall like a personal monument to contingency, a reminder that futures can vanish quietly.

Adult life repeats the pattern at higher stakes. In the lab, she overlooks the supernova evidence that others catch, and the discovery passes her by.

This moment is not just professional bad luck; it confronts her with the truth that ambition requires more than intensity. It requires openness, trust, and a capacity to miss things without collapsing.

Her refusal of therapy because of astronaut application rules exposes another kind of gatekeeping: institutions that demand mental health perfection from people shaped by real trauma. Her ambition pushes her to hide pain rather than treat it, which keeps her brittle.

Even her relationships suffer under the assumption that career must come first, as seen in the physicist’s departure and Steph’s later lonely profile snippets. Yet the book also shows ambition as a path out of paralysis.

When Steph finally becomes an astronaut candidate, it is not framed as a triumph that erases earlier losses, but as something earned through endurance and through learning how to accept help from Kayla, Nadia, and others. Aspiration is portrayed as powerful but dangerous when fused with control.

The story argues that reaching the stars is not only about working harder; it is about learning when to yield, when to be cared for, and when to admit that opportunity is never fully in one’s own hands.

Sisterhood, family loyalty, and the slow work of forgiveness

Steph and Kayla’s relationship is the emotional spine of the book, changing shape as they move from childhood dependence through adolescent rivalry and into adult rescue and repair. Early on, Kayla is both companion and mirror, someone who shares the family’s unspoken fears but expresses them differently.

Their fights at camp and the climbing gym show how siblings can become stand-ins for larger battles: Steph resents Kayla’s seeming ease with local life; Kayla resents Steph’s disdain for it and her readiness to expose Kayla’s choices. Yet when Steph tells Kayla about the lost Exeter scholarship, Kayla’s quiet support marks a turning point.

She may not share Steph’s dream, but she understands the cruelty of having it stolen. In adulthood, Kayla becomes the one who crosses the country to save Steph from self-destruction, cleaning her apartment, feeding her, and trying to guide her toward care.

That reversal of roles illustrates how loyalty in this family is not fixed; it is something re-earned as circumstances change. Their argument outside the psychologist’s office captures the hardest part of sibling love: wanting to pull someone toward safety while respecting their autonomy.

The Mauna Kea clash is another rupture, grounded in real moral stakes. Steph’s ambition feels to Kayla like abandonment; Kayla’s protest feels to Steph like sabotage of a dream she has clawed back from childhood.

Forgiveness only becomes possible when both acknowledge the limits of their power and the depth of their wounds. After their mother’s death, the sisters sit together through the decision to end life support, a shared act of love that cannot be argued away.

Kayla’s eventual forgiveness for Hawai‘i does not erase the harm; it contextualizes it within larger forces and within their lifelong bond. By the end, family loyalty is not portrayed as perfect harmony.

It is the choice to keep returning to one another, to tell truths at last, and to hold the light on for someone who keeps traveling far away.

Queer love, misunderstanding, and the need to be seen clearly

Romantic and sexual relationships in the book function as a parallel arena where identity, fear, and longing play out. Steph’s adolescent connection with Meredith begins in performance, a literal enactment of intimacy onstage that spills into real feeling.

The backstage kisses and hand-holding are not treated as trivial experimentation; they are a genuine awakening for Steph, who has been starved for tenderness and for a self that is not defined by family crisis. Meredith’s later rejection is crushing precisely because it reframes their shared moments as “misunderstanding” and forces Steph to confront how desire can be denied by the person who helped create it.

The pain is intensified by the social stakes of being a girl in a small community where names and reputations cling. This early rupture teaches Steph a basic lesson she carries into adulthood: love may feel real, but it can be withdrawn without warning, and sometimes you will be told it never existed.

Her adult relationship with the physicist repeats certain patterns with higher complexity. Here, Steph finds stability, shared work, and a partner willing to adapt to her intensity.

The domesticated rituals of their life together suggest Steph’s hope that she has become someone capable of commitment. Yet when the physicist leaves for Yale, Steph is confronted not only with abandonment but with her own refusal to imagine compromise.

The later realization that the physicist offered to reshape her life around Steph’s astronaut goal reveals how little Steph allowed herself to be loved in a way that required vulnerability. Dating profile snippets show Steph still circling loneliness, protecting ambition by keeping others at arm’s length.

Even the apology to Della demonstrates a changed ethic: wanting to acknowledge harm without demanding reconciliation. To The Moon and Back treats queer love as fully woven into the coming-of-age arc, not as a side plot.

It shows how being seen clearly—by lovers, by family, by oneself—is both the deepest desire and the hardest risk, especially for someone trained by trauma to expect disappearance.